Across Canada right now, there is an unprecedented railway blockade in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en people. The blockade, symbolic of the inevitable end of a seemingly infinite expansion of consumerism, is a culmination of the 500-year history of colonialism and genocide in the Americas. By refusing to consent to a pipeline construction through their unceded homelands, the Wet’suwet’en and their allies are choosing to end a dystopia – on their own terms.

Such courage is not rare, but it rarely makes the news.

Read this story in one minute

Maybe that’s why there’s a quietly spoken reactionary impulse among many climate people that the only path to victory is waiting for things to get so bad that change has to come. This narrative of climate action holds that things must get worse before they get better. But in the process, we are producing our own dystopia.

This misguided storyline holds that the right combination of duress in the right places – hurricanes hitting important cities all at once, combined with drought in major food producing regions, combined with several countries running out of water – would be enough to make heads of state ban fossil fuels and usher in, at long last, an era of climate sanity. They imagine there exists some unmet threshold of human suffering that would be repulsive enough to kickstart change on a huge scale.

Some of that rhetoric is already creeping into the conversation around the coronavirus, which has temporarily prevented up to a quarter of China’s greenhouse gas emissions. Lost in that news is, of course, the real human cost of the outbreak, not to mention economic stimulus packages that could boost global emissions long after the virus has been contained. Cheering on a virus because it reduces emissions isn’t progress. It’s eco-fascism.

These assumptions are sacrificial in nature. The idea that fear will lead us to action is well documented – but it doesn’t work that way.

Just look at the facts. The level of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere has not been seen in at least three million years, before modern humans even evolved. The past five years were the hottest five years in recorded history. In the meantime, the titles of climate-related books have steadily escalated – from The End of Nature to The Sixth Extinction to The Uninhabitable Earth, all warning of a future calamity.

And yet, in 2019, we still burned more fossil fuel than in any other year since the dawn of the industrial revolution.

A dystopia we can choose to change

There’s a simple lesson here: if we keep talking about inevitable disaster, we’ll eventually get disaster.

In his book The Great Derangement, the novelist Amitav Ghosh argues that for too long our narratives around climate change have focused on the tradeoffs between survival and disaster. "The great, irreplaceable potentiality of fiction is that it makes possible the imagining of possibilities," he writes. "And to imagine other forms of human existence is exactly the challenge that is posed by the climate crisis."

Climate change is a choice, not some unstoppable disaster we just have to accept will happen. Our biggest enemy might very well be apathy – us not caring while millions of species are going extinct.

The gradual industrialisation and commodification of life has led to a global civilisation that now depends on fossil fuels to function. And the fossil fuel industry, whose existence depends on this system, says we can’t realistically do without it. But of course, the opposite is true. We don’t need fossil fuels to survive – and we never did.

Climate change is a choice, not some unstoppable disaster we just have to accept will happen

What’s overlooked in this narrative is that the conclusions of climate science are already revolutionary in and of themselves. We need "rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society" in order to maintain a habitable planet, according to the climate scientists who wrote the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report in 2018.

We need to repeat that truth.

Climate dystopia isn’t the immeasurable winds or the towering infernos erasing entire cities. It’s the fact that when these things happen, we choose not to change. And that is a dystopia that could end any time we want it to.

These events indeed are unfolding all around us – from Australian wildfires to melting Arctic ice – not necessarily from our inaction or inability to change course, but from our choices to remain satisfied with disaster.

Writing a new collective story to fight the climate crisis

Fortunately, it is possible to respond with action that leads to positive change. That opportunity is presented to us every day.

There are many inspiring examples of larger-scale systemic change already coming into being. The success of the Urgenda lawsuit in the Netherlands was the first time ever that a high court ordered a government to reduce emissions on the basis of human rights, opening a new legal pathway worldwide. Ireland’s citizens’ assembly on climate has paved the way for direct democracies to set out bold demands for change. In New Zealand, last year’s school strikes reached a critical mass of 3.5% of the nation’s population, a point that research shows has been effective to meet its demands in every single prior non-violent protest movement in the entirety of the past 120 years of world history.

Just two years ago, climate change was hardly mentioned in US politics. It’s now the leading issue in the Democratic presidential primary. When Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in 2017, mutual aid networks sprung up to fill the gaps in the government’s poor response. Puerto Ricans are now helping form similar community-building networks all around the world as a basis for a new kind of locally determined way of living.

And the change doesn’t have to be on such a huge scale. Every day, there are people who gain greater awareness about the intersectional nature of our planetary emergency. For every conversation among friends that’s more about solidarity than solar panels, we move closer to understanding that success on climate isn’t just about reducing emissions – it’s about figuring out a new way to thrive, together.

A few months ago, during the height of the Australian wildfire crisis, the people of Hobart led a procession with burned remnants of the fires and placed them at the doors of the Tasmanian parliament. For years now, indigenous fire management practices, lost for generations amid the cultural erasure brought about by colonialism, have been making a comeback in Australia. These practices reconnect people to the land and can reduce fires by 40%. Even before the most recent bushfires, Australians were ready for bold change.

I recently asked my Twitter followers: what would it change for you if I told you we could still save the koalas, the coral reefs and all the places we love – but we would need to form a revolution? I received hundreds of responses, but the one that stuck with me most was simple: "I would have to trust others a lot more than I already do." It’s this trust in mutual aid, not competition, that could form the basis of a new collective story.

This is what a social tipping point looks like.

None of this is to say that things aren’t bad. They are. And it’s not to say it won’t take a lot of work to get us where we need to go. It will.

But we also have the Wet’suwet’en showing us the way. We don’t have to consent to injustice and catastrophe. We can write a new story, just like them.

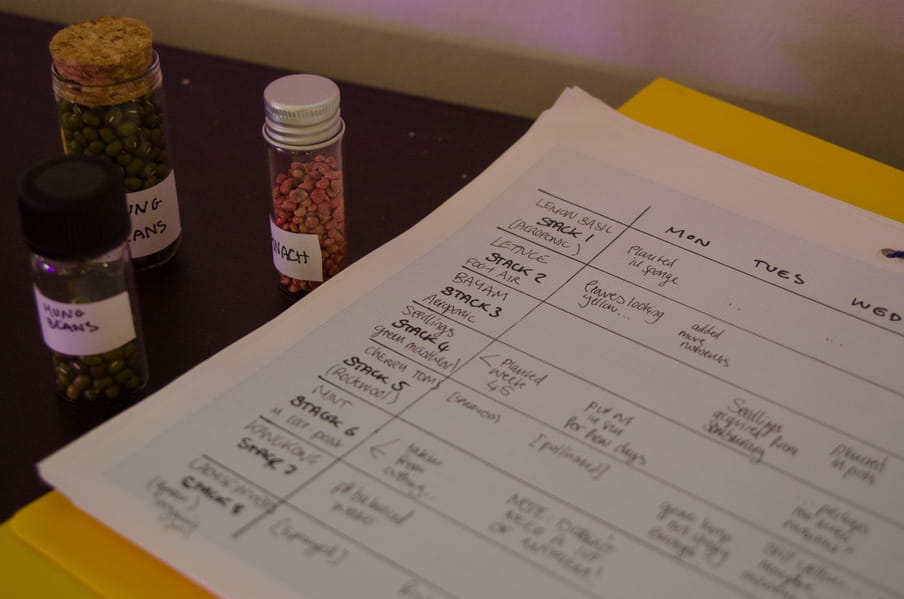

About the images

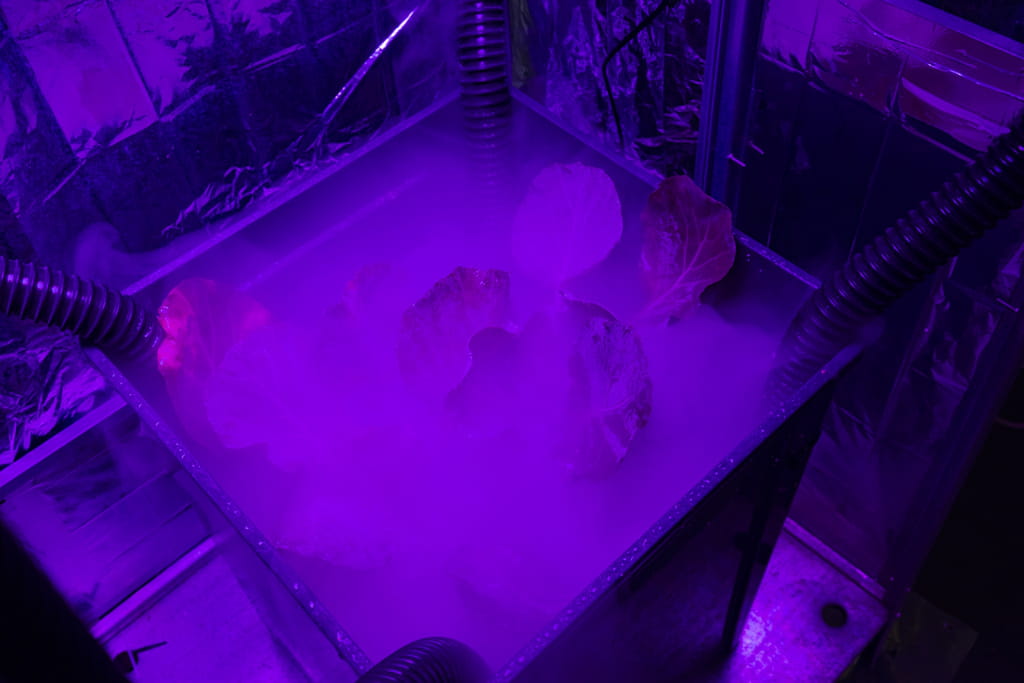

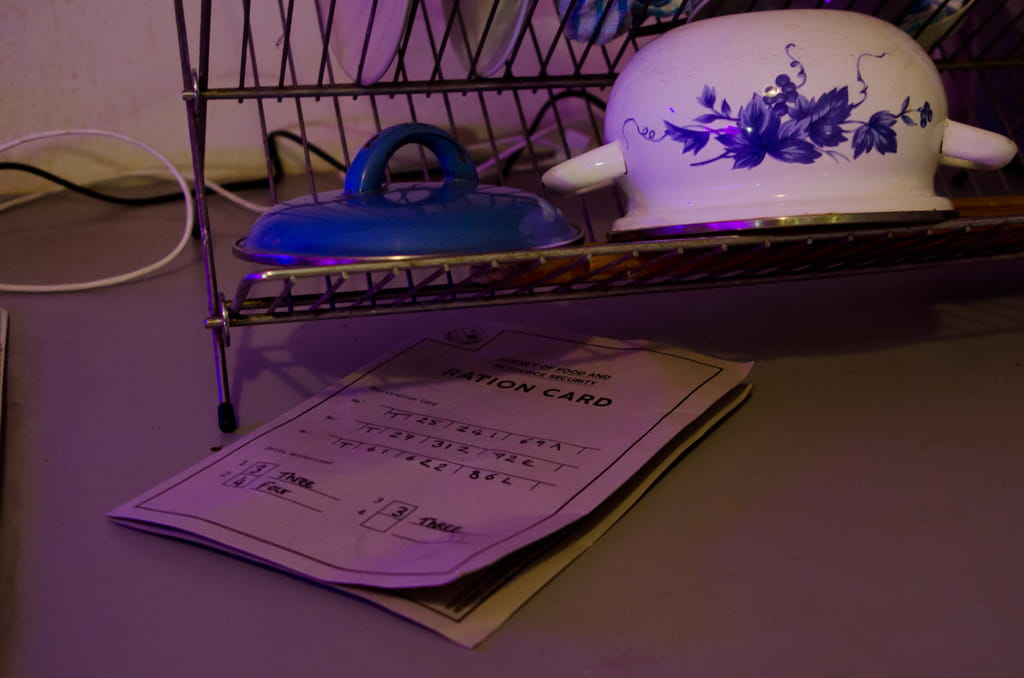

Founders Anab Jain and Jon Ardern call Superflux an Anglo-Indian design studio that aims to bring speculative design approaches to new audiences. Their installation Mitigation of Shock is currently showing at the ArtScience Museum in Singapore as part of the exhibition 2219: Futures Imagined until 5 April 2020. The installation is made up of a typical Singaporean home in 2219 in a future where climate change has completely changed the way people live their lives. The designers see the project as optimistic rather than dystopian. They hope to show that humans are a resourceful species, capable of radically adapting to new situations and environments and inventing new ways of living.

About the images

Founders Anab Jain and Jon Ardern call Superflux an Anglo-Indian design studio that aims to bring speculative design approaches to new audiences. Their installation Mitigation of Shock is currently showing at the ArtScience Museum in Singapore as part of the exhibition 2219: Futures Imagined until 5 April 2020. The installation is made up of a typical Singaporean home in 2219 in a future where climate change has completely changed the way people live their lives. The designers see the project as optimistic rather than dystopian. They hope to show that humans are a resourceful species, capable of radically adapting to new situations and environments and inventing new ways of living.

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Dig deeper

Politics is failing, but human networks could show us how to fix it

As the Better Politics correspondent I intend to explore solutions to the problems presented by ineffective political organisations. One place to look? The armies of individuals, plugging the gaps left by institutions.

Politics is failing, but human networks could show us how to fix it

As the Better Politics correspondent I intend to explore solutions to the problems presented by ineffective political organisations. One place to look? The armies of individuals, plugging the gaps left by institutions.