Sooner or later on the path to political literacy the inevitable question pops up: “What to do with all these things I’m learning?” Knowledge may be power, at least a power of sorts, but it’s not been much use recently given the multiple crises in today’s politics.

Read this story in one minute

History suggests that political progress – securing votes for women, ejecting colonial rulers or claiming equal rights for same-sex partnerships – requires collaboration. It happens when the personal activism of many people happens together. It’s a story of combination.

And activism can be a frustrating, even lethal, master.

Bolivian community organiser Oscar Olivera has some advice for anyone mulling that route: look down and around you before looking up.

After more than four decades in social movements, and with some famous wins tucked under his belt, the former shoe factory worker suggests that all action starts locally. No matter how global the issue.

Rather than counting on distant politicians to deliver on lofty promises – when, as in Olivera’s case, they were your former allies – a better strategy is to first make political friends of your neighbours, he told me in an interview:

“It’s important to look what’s happened above, with the politicians and the parties and what’s going on because that affects everything below, but the most important is to look at what’s going on below. How is our organisational health? How is the strength that we’re building? How are we navigating things below?”

It’s hard to guess from the quiet, diminutive Olivera that some 20 years back his was a pivotal role in Cochabamba’s landmark “Water War” when authorities tried to impose higher prices for their water supply. Between December 1999 and April 2000, tens of thousands of factory workers, street vendors, campesino peasant farmers and other Cochabambinos faced down the police and military on the streets of Bolivia’s third-largest city. They prevailed despite being set upon by dogs, showered with tear gas and lethally fired upon by snipers.

Speaking softly on a Zoom call linking his home in the Andean city of Cochabamba to mine in rural southwest France, Olivera told me how after months of pressure the protests succeeded in kicking the Aguas del Tunari consortium out of his home city. The companies involved in the privatisation of Cochabamba’s water utility included a subsidiary of Bechtel, a US construction company.

The protesters’ victory was hailed at the time as a poke in the eye for the forces of global neoliberalism. They achieved a rare reversal in the mainstream policy thinking which gives priority to private capital before public institutions as the primary mechanism for development and economic growth. Powerful supporters of this agenda, not least the World Bank, vaunted the efficiencies of the private sector and promised that benefits would trickle down to ordinary people.

Those arguments didn’t wash with residents of Cochabamba in 2000. Outraged at the prospect of paying even for the collection of rainwater, the motives for privatisation appeared to them to conceal yet another version of pillage – a new generation of conquistadors dressed up in suits and ties. Like many communities in South America, many Cochabambinos remain mired in poverty after five centuries of colonisation by European powers and their descendants.

The protests propelled Cochabamba onto the global political stage alongside the Zapatistas of southeast Mexico, who in 1994 rose up against a North American trade deal. Five years later, while the Cochabamba water privatisation was underway, anti-globalisation protesters from across the world convened on the World Trade Organisation meetings in Seattle, US.

Where followers lead

Olivera was among the leaders who negotiated with the then Bolivian government to terminate its contract with the privatised water utility.

Resistance to a neoliberal policy agenda didn’t end with the defeat of the private consortium which took over Cochabamba’s water supply. Momentum from the Water War buoyed the political fortunes of Bolivia’s Indigenous leader Evo Morales, a politician who Olivera knows well. Morales won power in 2005, carried by a surge of optimism and hope by Bolivia’s urban and rural poor. His rise to the presidency was part of a so-called “pink tide” of avowed left-leaning leaders coming to office across Latin America.

That was when things started going wrong, reckons Olivera: “In Bolivia, this is the situation, we believed in a person, in a political apparatus, that they could bring change and, at the same time, we became disorganised, we stopped organising.”

President Morales, the great hope of Bolivia’s Indigenous people, signally failed to fulfil his original mandate. In 2019, after attempting to secure a fourth term in government, he was hounded from office: questions of how and by whom remain charged as Bolivians prepare for a re-run of presidential elections later this year.

“Instead of getting this change that we were looking for, Evo Morales betrayed this popular agenda that we lay before him before the end of 2005, before he was president, and in which we had so much hope,” Olivera tells me.

Selecting student representatives by lottery creates political space for candidates who might never have imagined standing for election in a ballot

The political mandate of the Morales administration comprised two main parts. First, a new approach to national resources as public goods for the benefit of all – to replace the extractivist approach of turning all resources into private merchandise or commodities. Second, to end the party system of democracy where a few leaders take all decisions, by creating new forms of democratic participation.

Neither came about, while the social movements that had brought Morales to power withered away.

A crucial mistake by the organisers of these movements was to drop their guard after winning formal political power, a pattern repeated across Latin America. “In these 20 years, I believe there’s been a process of weakening, of undoing of the popular power and the social fabric that was so important in the Water War, for example, in terms of being able to set the popular agenda,” says Olivera.

“I believe that the destruction of the social fabric that’s so important has been the worst in the governments, the so-called popularist, leftist, Indigenous governments that have taken power in South America – in Bolivia, in Brazil, in Argentina, in Ecuador, in Venezuela.”

The cardinal lesson that Olivera takes from all that? It’s better to lead – and to learn how to lead – as a community, than to remain ignorant and powerless by committing to follow a leader, or caudillo (as they’re called locally). “So, before the Water War, and after the Water War, our politics has been one of: “Who should I follow behind? Who should I get behind in this simulated democracy, in which every few years we have to make this decision? It’s a sort of politics that doesn’t work.”

On organisation – by lottery

Olivera speaks softly and deliberately in Spanish, his words interpreted for our interview by an American ally, Adam Cronkright, who is about half his age. The two met when Cronkright came to Bolivia after the Occupy Wall Street protests of 2011 petered out.

Encouraged by Olivera, Cronkright came to Bolivia to road test his ideas for a democratic “lottery” in Cochabamba high schools, where the local organiser was experienced in working with students on organic agriculture projects.

The result was Democracy in Practice – a non-profit co-founded by Cronkright and Olivera’s namesake Raúl, no relation, with Oscar on the board of advisers. As an alternative to elections, DiP advocates for selecting student government members by lottery: coloured beans are drawn from clay pots to determine who serves a term.

The lottery mechanism broadens the base political participation beyond the louder, more popular pupils who typically win elections, regardless of any merits they might bring in office. It creates the space for others to learn the art of politics by doing, including students who might never have imagined standing as candidates in a ballot. Applying shorter terms and tackling real issues, the idea is to give more students a sense of governing themselves.

It’s hardly surprising Olivera’s a fan. So too, now, is the popular US author Malcom Gladwell, who recently floated the idea in a US context. DiP’s work on a proof of concept in Cochabamba schools, now extended to include a range of how-to manuals for schools and universities anywhere, has helped to sustain Olivera’s motivation through the political ups and downs in his life and work.

Because there are ups and many downs in a life of political action.

Throughout our Zoom call, Olivera punctuates the discussion with gentle gesturing of his hands to make each point. His appearance is anything but the feisty warrior against bad government and global corporations. That his mood seems quite subdued may be a reflection of the bigger picture: politics isn’t all flowers right now. Not locally in Cochabamba, nor elsewhere across the world.

“Our organisational health is really bad right now below. We’re weakened, we’re divided, we’re disorganised. We have lost the reciprocal trust in our society. We don’t have any reliable ethical organisational reference point, one that’s morally trustworthy.”

Except for Olivera himself, perhaps; though he’d never say that.

The grassroots organiser greeted on the streets as “ Oscarito ” has always declined to join the governments which were brought to power by movements he helped lead.

Olivera self-identifies as an organiser rather than an activist, which means working up agendas and the strategies required to put them into place. His prize money, as winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2001, was channeled to the non-profit organisation which he directs: Fundación Abril. It works to promote – you might have guessed – alternative participatory and democratic processes in labour negotiations and the management of water as a common good.

Such work is always for the long haul, he says.

“There’s a process of permanent resistance around the world, and in Bolivia going back centuries. At the same time there’s a process of construction.” This involves people recovering their history and values: Olivera himself is Aymara, an Indigenous people of the Andes now mainly living in Bolivia, Peru and Chile. Only by developing collective understanding of concepts like “democracy” and “politics”, he explains, can societies move forward together.

The moral arc of pragmatism

Olivera’s political approach is focused on what people need rather than high-flown rhetoric. “For us, politics means the ability to focus on the day to day. This might be water, this might be sanitation, this might be the pandemic but it’s always about the day-to-day struggles. Working in small collectives, we’re not looking to build a political party or a large organisation like La Coordinadora of water in the Water War. That’s not possible today.”

His advice seems as sensible for my local French village as it does for the 1.3 million inhabitants of Cochabamba. “It starts with our family, it starts with our neighbourhood, it starts with our water committee. The focus is on rebuilding community."

Which brings us to this question: what is community? “It starts through each and every one of us, the people. This is something that we’re seeing now in Bolivia with the pandemic. The government has not been able to help, has not responded to the pandemic. It can’t and doesn’t. The only real response to the pandemic in Bolivia has been with people organising themselves.”

A flash of weariness passes quickly: to this day, the water infrastructure in Cochabamba is hampered by bureaucracy and lack of investment

Focusing on local and practical priorities does not preclude a wider perspective, nor any narrowing of Olivera’s political commitment. “When I talk about resistance, I want to be clear that the oppressors haven’t really changed: they’re pretty much the same. There was the colonial period and now the neo-colonial period. We have enemies in the form of climate change, we have enemies in the form of corporations, we have enemies in the form of politicians who are exactly the same, in every country.

Over the past 20 years, Olivera sees in retrospect a mixed picture of victory and defeat: the euphoria of turning back the tide of privatisation is set against the brokenness of politics everywhere today, including in Bolivia. “We have this democracy that’s a caricature of democracy and we have enemies in the form of militaries and police forces. Throughout the world, enemies are the same.”

And to this day, the water infrastructure remains poor in Cochabamba, hampered by bureaucracy and lack of investment.

“It’s really complicated because in this time, these 20 years, we’ve learned a lot of things. We’ve learned how to kick corporations out of our country, we’ve learned how to change politicians and take down governments, we’ve learned a lot in the process. The issue of reconstituting, rebuilding the social fabric is something that takes a long time and a lot of work.”

Olivera acknowledges a rare flash of weariness, though it passes quickly: “Building things, that’s a much more challenging and longer task. Sometimes one’s strength, it wanes.”

Asked to reflect on Martin Luther King’s famous claim about the arc of the moral universe – King spoke of it “bending towards justice”, though my question revises this destination to "democracy" – Olivera is determinedly hopeful.

“We’re progressing in spite of it all. I believe that people are starting to wake up to what democracy means. And democracy is really about who decides. We’re starting to see that having these politicians and corporations decide important things against the interests of people, decide things that affect us people, that that’s not democracy.”

The challenges ahead are steep and daunting: “It’s going to be painful, it’s going to be a struggle, it’s going to take a long time”. And the eventual destination, the outcome of that ongoing struggle? On this litmus test of political conviction, the stalwart of Cochabamba’s Water War has no room for doubt: “We are going to move to a real democracy and that’s possible.”

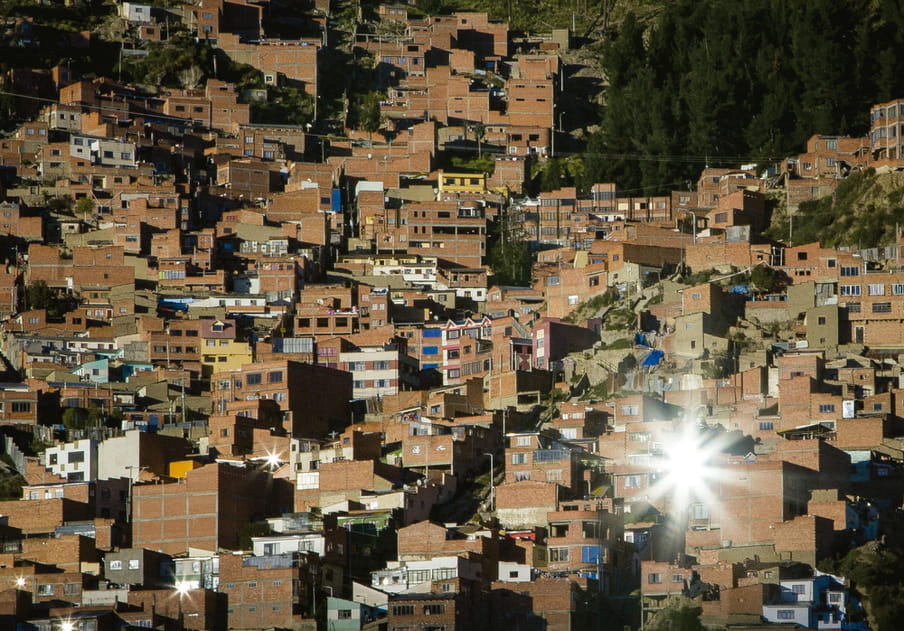

About the images

Shoeshiners face discrimination in Bolivian society. They’re often assumed to be alcoholics, drug addicts or petty thieves, and many hide their identity behind masks. Photographer Federico Estol wanted to document their stories, but how? He wanted to avoid perspectives typical in the mainstream media, by working closely with shoeshiners’ communities in La Paz to create a new narrative. Shine Heroes combines photography with elements from graphic novels, in a participatory approach where the workers could decide how they are portrayed. Their masks, often perceived as a cause for shame, are transformed into empowering symbols fit for a modern, urban Batman. Participatory photography is a political tool for self-representation, deployed to re-frame community and personal histories (Veronica Daltri, image editor).

About the images

Shoeshiners face discrimination in Bolivian society. They’re often assumed to be alcoholics, drug addicts or petty thieves, and many hide their identity behind masks. Photographer Federico Estol wanted to document their stories, but how? He wanted to avoid perspectives typical in the mainstream media, by working closely with shoeshiners’ communities in La Paz to create a new narrative. Shine Heroes combines photography with elements from graphic novels, in a participatory approach where the workers could decide how they are portrayed. Their masks, often perceived as a cause for shame, are transformed into empowering symbols fit for a modern, urban Batman. Participatory photography is a political tool for self-representation, deployed to re-frame community and personal histories (Veronica Daltri, image editor).

Dig deeper

I’m a middle-aged white man. Instagram taught me why #statuesmustfall

Protestors in London graffitied the words “Was a Racist” beneath Churchill’s name on a bronze statue of Britain’s war-time prime minister. I certainly agreed with their statement, but baulked at making this point publicly in my journalism: my own self-identifying as “not racist” wasn’t “anti-racist” at all.

I’m a middle-aged white man. Instagram taught me why #statuesmustfall

Protestors in London graffitied the words “Was a Racist” beneath Churchill’s name on a bronze statue of Britain’s war-time prime minister. I certainly agreed with their statement, but baulked at making this point publicly in my journalism: my own self-identifying as “not racist” wasn’t “anti-racist” at all.

If you want to change a culture, you have to change more than the law

As Better Politics correspondent, I’ve written about how robust human networks can plug gaps left by governments and institutions. But how do you end barbaric practices like FGM that are deeply ingrained in identity?

If you want to change a culture, you have to change more than the law

As Better Politics correspondent, I’ve written about how robust human networks can plug gaps left by governments and institutions. But how do you end barbaric practices like FGM that are deeply ingrained in identity?