On the walls: photographs of snow-covered mountain peaks and vast, verdant forests. On the table: a pile of books on environmental activism. In the corner: a small group fiddling with a surfboard, and busy preparing a protest action against Norwegian oil company Equinor’s plans to drill for oil off the coast of Australia.

Am I at Greenpeace? No.

This is the scene at Patagonia’s European headquarters in Amsterdam.

Read this story in one minute

Patagonia is an American clothing brand with sales of about $1 billion per year. It’s one of the world’s biggest and best-known names in outdoor wear, with more than 50 stores around the world. But if you think that Patagonia is just another manufacturer of fleece jackets, sleeping bags and backpacks: think again.

For one thing, it’s been known to urge customers not to buy too many of its products. For another, there’s a camper van of Patagonia staff driving across the US to mend customers’ beloved but worn-out products.

"Chouinard is attempting to challenge the culture of consumption at the heart of the global ecological crisis" – Naomi Klein

And then, as I see with my own eyes, there’s the company’s long-standing commitment to fighting everything that hurts the environment – a whole history of campaigns against ecosystem-destroying dams, oil drilling, pipelines, deforestation and governments which deny climate change.

Patagonia’s mission statement, far from something blandly typical – along the lines of: we make the best equipment to get the best out of outdoor adventures – is simpler, and much braver: “We’re in business to save our home planet.”

Patagonia wants to save the Earth.

That sounds paradoxical from a company raking in a billion dollars a year from selling clothes, with all the ecological impact that implies. Is this really the same company that wants to save the world from environmental crisis?

The journalist and activist Naomi Klein strikes a critical note. In her foreword to Let My People Go Surfing, a memoir in which Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard (81) reflects on his life in the business world, Klein asserts: “I don’t endorse multinational corporations, even ‘green’ ones like Patagonia.”

Instead, Klein admires Patagonia as a unique “experiment”. What Chouinard is attempting to do, she writes, is “more than change a single corporation – it is an attempt to challenge the culture of consumption that is at the heart of the global ecological crisis”.

I want to know more about that idealism, which is why I’ve come to Patagonia’s European headquarters. How exactly is Patagonia making the planet better? And is their approach working?

The outsider inside Patagonia

As the people with the surfboard start pulling out wetsuits from storage lockers, I take the stairs to where Vincent Stanley, Patagonia’s "Director of Philosophy", is waiting for me in a small conference room. Speaking with Yvon Chouinard in person won’t be possible: “These days he’s out fishing a lot,” Stanley tells me.

Stanley is Chouinard’s nephew. Aged 20, he began to help out at his uncle’s company, a predecessor of Patagonia. “It started out as a summer job, but I kind of stayed with it my whole life,” he says with a grin. Now 68, Stanley is dressed in a chequered shirt, blue jeans and athletic shoes. “At Patagonia I was always something of an outsider. Everyone else surfed and climbed, but I was never into the extreme sports,” he says in a measured tone.

After working as a sales manager for 20 years, he quit to pursue his passions: writing books and poetry. But a few years later, he was back. “Patagonia was focusing more and more on environmental work, which was very interesting to me. I helped write the ads in The New York Times and The Washington Post that ultimately got the Edwards Dam removed. It was our first truly successful environmental campaign. That was the kind of work I loved. After that we started to look at our own supply chain. That was very eye-opening and, really, a big wake-up call for us.”

Later the same day, I hear him talking to some of the employees in Amsterdam about the end of capitalist society: “Of course we’ve asked ourselves whether we shouldn’t just shut down Patagonia, if we were really being true to our ideals, because everything we do causes some kind of damage. But we haven’t done that, because we think that this is the way to keep putting pressure on our society to do the right thing.”

See the price tags and weep

Patagonia is a name that you often hear in the context of sustainable fashion. And yet I had never really learned much about them. Three years ago, I was planning a two-week hike in the Pyrenees and looking for environmentally friendly outdoor wear. I poked around their website.

Online I saw some vital statistics, like Patagonia’s use of recycled materials and organic cotton. Not particularly exciting, I thought; plenty of companies are doing the same these days. And when I saw the price tags, my heart sank.

Patagonia was among the first labels to recycle PET bottles into clothing. It offers both a lifetime warranty and a free repair service

But over the past year, I started to learn more about Patagonia. This time, what I learned held my attention. People in the fashion industry who I spoke to, or read about in interviews, often refer to Patagonia as an example, a source of inspiration. A few months ago, when I started to research the cotton farming industry, Patagonia came up again.

Patagonia was one of the first clothing companies in the world to fully switch to organic cotton. And that was back in 1996, long before most other labels were even aware of the damage that conventional cotton farming was doing to people and the environment all over the world. It was a revolutionary move, because at that time there was hardly any organic cotton available anywhere. So Patagonia started creating its own partnerships with cotton farmers.

Before that, in 1993, Patagonia was one of very few labels to recycle PET bottles into its clothes. And since 1997, the company has been using hemp, one of the world’s most sustainable materials, in its collections. It’s one of the few companies that offer both a lifetime warranty and a repair service (free).

Far from chasing the sustainability trend, I saw Patagonia was out in front of the pack, showing others the way. From choice of materials, to design of the products, to setting up environmental campaigns – the company does its research thoroughly and tests every decision for quality, functionality and environmental impact.

A growing sense of sustainability

Not that Patagonia started with the ideal of doing things differently. Nor was it a socially and environmentally conscious company from day one. In fact, the business which ultimately became Patagonia started out as a way for Chouinard to make some quick money to fund his climbing expeditions.

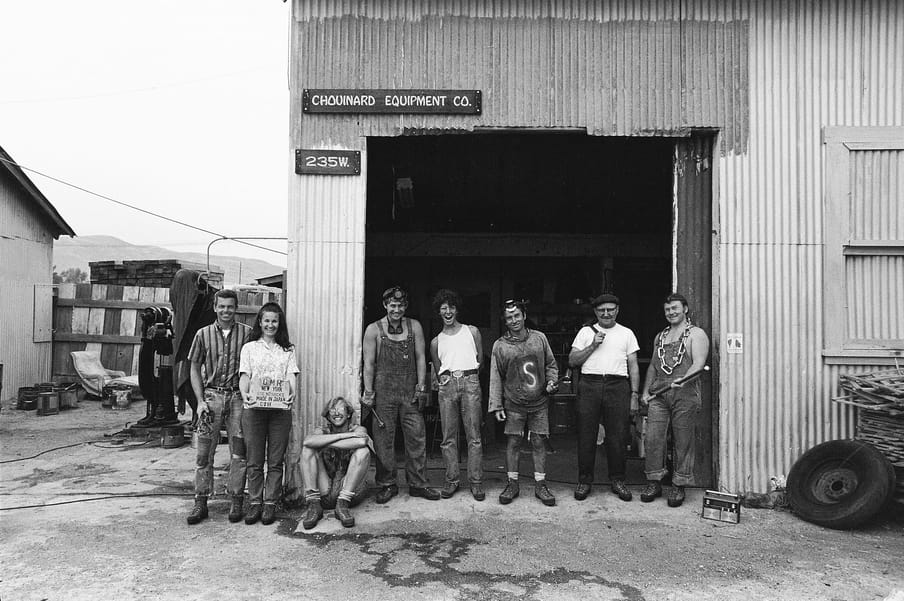

Before Patagonia was founded in 1973, Yvon ran Chouinard Equipment, from the back of his car – selling climbing equipment made by hand with a secondhand forge, using techniques picked up from the passion for climbing and the outdoors which Yvon had pursued since the age of 14.

In the backyard of his parents’ house in Burbank, an outlying suburb of Los Angeles, Yvon converted an old chicken coop into a workshop and store. “I still remember him in that backyard, standing over the coal fire, forging, in his bare feet,” his nephew Stanley recalls. “Even when it rained, he didn’t wear shoes. He lived a simple life out of the trunk of his car, had basically no money, he was my boyhood hero.”

But the tools which Chouinard cobbled together left scars, deeply marking the natural environment. Climbers would generally leave steel pitons behind in the rock, partly because they could be used by other climbers, but mainly because the metal rods tended to break off when you tried to remove them. Even if they didn’t break, they left a lasting hole. Motivated by a strong belief that climbers should not be damaging the environment they climb in, Chouinard developed new, aluminium chockstones which served the function of the piton but could be removed easily without damaging the rock face.

Clothing was easier to make, and sold well

The new chockstones were a success. Chouinard was able to hire friends and family to help out with the business. One day, on a climbing holiday in Scotland, Chouinard’s brightly coloured rugby shirt proved such a hit among other climbers that he decided to order a few more and sell them.

And that’s what started the ball rolling: in 1973, Chouinard founded Patagonia with the intention to make and sell clothing. Unlike the pitons and chockstones, for which Chouinard and his people toiled over a hot forge, this was work they could do from behind a desk.

And the stuff sold well.

But what Chouinard had not yet realised was that the same colourful, high-quality and lucrative shirts left a trail of environmental damage much more devastating than the holes in a few rocks.

A planet changing before his eyes

Twenty years later, after Patagonia had grown into a company with sales in the tens of millions of euros per year, the truth began to sink in. “I saw that deterioration with my own eyes when I returned to climb or surf or fish in places I knew, like Nepal, Africa and Polynesia,” Chouinard writes in his book.

“In Africa, forests and grassland were disappearing as the populations grew. Global warming was melting glaciers that had been part of the continent’s climbing history … In Wyoming, where I had spent summers for 30 years, I saw fewer wild animals each year …”

Chouinard began to study ecology. He read weighty tomes about biodiversity, about the animal and plant species that were being lost through deforestation. He understood long before most people did that nature and the climate were under real pressure, recalls Stanley: “Those concerns had a big impact on everybody who worked in the company, even then; because of him, other people, including me, started to get engaged with it, too.”

He saw how this young man, with virtually no resources, brought life back to the river

Around the same time, Chouinard met a young activist who was working to stop the construction of two dams in the Ventura River in southern California. He saw how this man, with virtually no resources behind him, was able to do things that brought life back to the river, and give nature the chance to recover.

Chouinard decided to start supporting small environmental groups. Each year, he donated 10% of Patagonia’s profits to groups working to defend nature and the environment (later, this figure would become 1% of total annual sales, a much bigger number). Chouinard and his people also started to speak out on political issues. They were against free trade, and took out advertisements in the media to present a critical view on international free trade agreements such as NAFTA and GATT.

Even then, the impact of Patagonia’s business on people and planet was largely overlooked. “Only after we had gained the confidence to take on some of the enemies of nature were we able to see the enemy we had been missing the whole time: the enemy in the mirror,” Stanley later wrote in the book The Responsible Company, about Patagonia’s first 40 years.

What they saw in the mirror didn’t look good.

Patagonia ignored its own footprint for 15 years

Fast-forward to 1988. Patagonia had just opened a store in Boston. After a few days, multiple employees were complaining about severe headaches. Initially the prime suspect was the ventilation system, but after further investigation the culprit turned out to be the cotton clothing lines. To prevent wrinkles and reduce shrinkage, cotton had been treated with formaldehyde – a notoriously aggressive chemical.

Stanley: “For fifteen years, we had been running our clothing business without asking ourselves what happened to the wastewater from the dyeing process, and without really worrying about the working conditions in the places where our garments were made. We realised that we were running our company just like everybody else. So what other kinds of damage were we causing?”

"Concern over transitory fashion trends is specifically not a corporate value" – Patagonia’s mission statement

After that wake-up call, alarm bells sounded when the sales figures started going south. After a long period of sustained growth – from 1980-1990, sales rose from 20 to 100 million dollars – by the summer of 1991, Patagonia was in crisis.

Patagonia’s board asked Jerry Mander, an American activist and author, for advice. Working with a team from Patagonia, he drafted a statement of binding values for the company to defend. Sample extracts: “All decisions of the company are made in the context of the environmental crisis. We must strive to do no harm,” and “Maximum attention to the quality of the product,” meaning that everything should last as long as possible with minimum possible use of natural resources in production. And: “Concern over transitory fashion trends is specifically not a corporate value.”

Values versus trends

Patagonia’s first assessment of the environmental impact of its clothing production came in 1994. “We learned that 85% of our ecological footprint was caused by the manufacture, dyeing and finishing of the fabrics,” Stanley recalled.

The previous year, the company had started processing recycled PET bottles as a polyester substitute; recycled bottles were going into the clothes. By 1996, Patagonia eliminated all conventional cotton from its collection, replacing it with organic. The shift was “one of the hardest things we ever did,” Stanley told me.

“When we started buying the cotton directly from the farmers, we were basically breaking the supply chain. That meant we had to go out and find spinning and weaving mills – the place where the cotton fibres are turned into threads and fabrics – that were willing to work with us, and that were willing to start working with only organic cotton, too. And then we had to explain to our customers why we were raising the prices of all our items by three to five dollars.”

Patagonia was building up its “green” reputation one step at a time. Over the same period, Chouinard refined the new mission statement: “Build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.”

A path strewn with obstacles

When Patagonia decided, in 2011, to put its entire production chain under the microscope – investigating not only its clothing manufacturers but also the suppliers and their sources of fabrics – red flags appeared everywhere. One supplier in Taiwan, for example, employed migrant workers in abominable conditions on desperately low wages: migrants worked day after day to pay off a debt, which they had taken on in order to land the job in the first place.

"Making your own products is a completely different ball game. Basically nobody does that" – Vincent Stanley

Next to sourcing more sustainable materials, from 2013 the company took steps to ensure that workers in the supply chain receive a living wage. While supporting NGOs, Patagonia launched more campaigns. And the company opened the largest clothing repair facility in North America, currently employing 69 full-time staff, which carried out more than 50,000 repairs in 2017.

This was a path strewn with obstacles.

In 2015, Greenpeace accused Patagonia of using toxic chemicals in its products. In the same year, the company was confronted by international animal rights organisation PETA with photos of cruel practices on an Argentinian sheep farm from which Patagonia sourced wool. The company severed the partnership almost immediately; a year later, Patagonia created its own new standard for wool, setting defined criteria on animal welfare and land use for all its wool suppliers to meet.

Exploitation and animal cruelty are problems inherent to a clothing industry that depends on outsourcing. So why didn’t Patagonia choose to keep control of the entire supply chain in its own hands, by making all its products itself?

“There’s basically nobody in the industry who does that,” Stanley replied when I asked that question. “Making your own products is a completely different ball game. If a brand like ours had its own factory, with all the machinery to make something like the Synchilla pullover, let’s say, or some particular type of underwear, and then we decide to stop making that product, then we’re stuck with all those machines.”

Instead, Patagonia looked for ways to reduce its total number of suppliers: “Fifteen years ago we had 150 factories around the world that we were working with, today that number is 50.”

The maverick story takes root

Despite the concerns and controversy over its environmental impact, Patagonia grew steadily. Being a family business didn’t seem to hurt: as the sole owner, Yvon Chouinard had a great deal of control over the decision-making. “You would never be able to take such risks with a public company,” explained Rose Marcario, CEO since 2014, “I mean, we made a documentary about tearing down dead-beat dams. There is no public company that would have financed that movie.”

Another factor is Patagonia’s backstory of maverick activism – a record that plays well with consumers, and particularly young people. Under Marcario’s leadership, the company doubled down on its activist credentials – and went one step further: Patagonia got political.

In 2017, Patagonia sued the Trump administration over its decision to remove statutory protection from two national monuments in Utah. The company was quick to openly back the Green New Deal. When Trump announced a massive corporate tax cut, Patagonia responded by pledging to donate its $10 million tax saving to environmental organisations.

Do Patagonia customers buy because of the quality of the products, or because they want to make a statement?

Whether it’s due to the marketing value of activism, or simply a long economic boom, Patagonia’s sales quadrupled under Marcario’s leadership. When I asked Stanley whether customers buy for product quality or because they want to make a statement with their purchasing power, he answered with a telling anecdote.

In November 2016, right after Donald Trump was elected president, Patagonia pledged to donate all its Black Friday profits to good causes. Sales on that day exceeded $10 million, but in the following days many consumers returned their products to the stores. Often slightly embarrassed, they told similar stories: in fact, they did not need their purchases, but had rushed out to buy Patagonia products because they wanted to signal support for the company’s message. And they got their money back.

Patagonia has been accused of hypocrisy – the harder the company fights against the consumer society, the bigger its business grows. That contradiction is apparent in its advertising and videos, from which you would think that Patagonia’s target group is made up of unwashed dirtbag climbers, dyed-in-the-wool environmentalists, and outdoors types living in their cars. But then, looking at the prices, you have to wonder how any of those people would ever afford a Patagonia product. It’s this dissonance which earned the company its nickname: “Patagucci”.

Big companies are ‘bad guys’ – until you become one

The tension between commercial growth and protecting the environment has always been a part of Patagonia. Before he ran a business himself, Chouinard saw big companies as “the bad guy”. But no matter how good you are, you will always have some kind of impact. “Our mission statement says nothing about making a profit,” Chouinard has written, “However, a company needs to be profitable in order to stay in business and to accomplish all its other goals, and we do consider profit to be a vote of confidence, that our customers approve of what we are doing.”

There’s probably something to that. But how much growth is enough? I put it to Stanley that there’s a world of difference between a little profit and a lot of profit. A paradox which Stanley acknowledged: “The bigger we get, the harder it is to suppress our environmental impact, simply because we are making more clothes.”

Patagonia makes a distinction between “bad” growth and “good” growth, he explained. Bad growth is when people engage in continued consumption without attaching value to the lifetime of a product or how it is made. Good growth means that people buy better products that last longer, which pushes back against the “disposable society”. Patagonia wants to do things that will help good growth win out over bad.

Is Patagonia feeding the consumer society?

Is it working? Didn’t Patagonia’s infamous “Don’t buy this jacket” campaign actually increase sales of that particular jacket, as The New Yorker reported? Surely Patagonia is feeding the consumer society?

I ask Stanley.

“That’s a tough question. I don’t know. Sometimes when I walk into one of the stores and I see all the colours, I think oh my gosh, we really do make things look really attractive, don’t we. But you want everything you make to be good and look good; in the end that’s a part of quality, too.”

"Sustainable" isn’t a word that you’ll hear much at Patagonia: “That would be implying that you are giving something back to nature instead of taking something away,” according to Stanley. “And we’re not doing that. That’s why we use the word ‘responsible’. We’re doing everything we can. We are active on a serious level with repairing our clothes and offering a platform for secondhand clothes. The most important thing, I think, is ultimately that you can change the relationship between the consumer and the product. Get people attached to a product so they want to keep it, by repairing it.”

To reduce its environmental footprint, Patagonia has set an ambition to be CO₂ neutral by 2025. That means completing a transition to 100% renewables for every link in the supply chain, from cotton plantations to the weaving mills, spinning mills, factories, warehouses and stores, while replacing all petroleum-based plastics (polyester, nylon) with biodegradable materials.

Does that make Patagonia unique? No. There are certainly other companies that are recycling their products, sourcing organic raw materials, and taking serious measures to reduce or improve their social and environmental impact. But Patagonia is unusual: its focus reaches beyond its own footprint, and the company is busy working to promote responsible business practices across the industry.

Building a movement

Patagonia is a prominent and driving force behind the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC), an organisation working with fashion labels to create an index that measures the environmental and social impact of companies and manufacturing. This coalition is endorsed by some of the world’s largest companies, including Nike, Adidas, H&M and Inditex (Zara).

Next year, the SAC will publish an index to enable consumers to assess how the various brands rate on labour standards and social impact. “It’s important to be measuring everyone against the same standard,” Stanley says. “That’s one way of preventing greenwashing.”

Yvon Chouinard also founded “1% for the planet”, an initiative which calls on companies to donate 1% of their gross annual revenues to environmental and climate causes. Since launch in 2002, more than 1,800 companies have signed on.

A few years ago, Patagonia established Worn Wear, a marketplace for secondhand and repaired Patagonia items. A good move, and not just from an environmental standpoint; the lower prices allow less affluent customers to buy into the brand. It’s an idea recently taken up by H&M in Sweden, which has announced its own plans to start reselling secondhand H&M clothes.

Then there’s “Responsible Wool and Down Standard”, another Patagonia idea: a list of criteria that all wool and down suppliers must meet, with strict requirements for animal welfare. Companies that want to ensure that their materials are sourced in the most animal-friendly and sustainable way possible can commit to this initiative, which includes an auditing process for suppliers.

The sum of these initiatives has earned Patagonia both social licence and an influence beyond its size as an independent retailer. Patagonia has become one of the most influential international apparel brands.

Can making clothes save the planet?

In her introduction to Chouinard’s book, Naomi Klein writes that what draws her to his story is “a sincere attempt to address the core tension between the market’s demand for endless growth and the planet’s need for a break”.

It should be clear that Patagonia is not just another company chasing profit at any price, but can this fundamental tension between growth and the finite resources of the planet be resolved? Klein doesn’t have an answer. “After all, Patagonia keeps on growing,” she writes, “and we keep buying more of its products.”

When I look at the company’s self-declared ambition to save the world from an ecological disaster, I have to ask whether manufacturing clothing is any way to achieve that goal.

At the same time, I recognise it will be possible to achieve greater impact from the inside, by working in partnership with other companies, than as an activist organisation on the sidelines. Chouinard makes exactly this case: “If the world won’t listen to me as an individual, perhaps they’ll listen to the voice of a company of a thousand individuals.”

And while there are already plenty of activists and campaigns, I can’t think of any other company like Patagonia.

This article first appeared on De Correspondent. It was translated from the Dutch by Kyle Wohlmut.

Dig deeper

Apocalypse never: why climate catastrophe won’t make us change

There’s an idea among many ‘climate people’ that large-scale environmental disaster will finally force governments to act. But talking about catastrophe will only bring catastrophe. Instead of waiting for disaster, there are other ways to bring about radical climate action.

Apocalypse never: why climate catastrophe won’t make us change

There’s an idea among many ‘climate people’ that large-scale environmental disaster will finally force governments to act. But talking about catastrophe will only bring catastrophe. Instead of waiting for disaster, there are other ways to bring about radical climate action.

Thanks to this landmark court ruling, climate action is now inseparable from human rights

The Dutch supreme court has ruled that the state must reduce its CO2 emissions. The impact will be felt around the world.

Thanks to this landmark court ruling, climate action is now inseparable from human rights

The Dutch supreme court has ruled that the state must reduce its CO2 emissions. The impact will be felt around the world.