Weighing in at a whopping 3,200kg (7,055lb), the Ford Excursion is an environmental offence on wheels. The rectangular, mega-monstrosity SUV is so heavy it was actually exempted from US fuel economy rules for passenger cars. That’s 3,200kg used to transport a 70kg (154lb) person to the supermarket – or 45kg (99lb) of car for every kilo of passenger.

Read this story in one minute.

Such proportions haven’t been seen since Hannibal led the armies of Carthage across the Alps on an African forest elephant to invade the Roman Republic.

By way of comparison, the ratio of a bike is 0.2kg (0.44lb) of vehicle for every kilo of person. A Vespa scooter: 1.1kg (2.4lb). A passenger bus: 5kg (11lb). A full Boeing 787-9: 6.3kg (13.9lb). A Japanese bullet train: 7.7kg (17lb). And the humble Fiat 500: 13kg (28.7lb).

In the last decades, cars have put on an enormous amount of weight. By now, the average European car weighs about 1,400kg (3,086lb). In the US, they’re even a weight class higher: 1,850kg (4,079lb).

Researchers estimate that if the weight and engine capacity of European cars had stayed the same between 1980 and 2006, fuel consumption would have gone down by about 20%. This would even have been 40% for US cars.

Any progress made thanks to energy agreements, climate accords and Green New Deals has partly been negated by the rise of incredibly heavy cars. The International Energy Agency (IEA) showed recently that the largest source of increased emissions in the last decade is the electric power sector (ie lots of coal power plants in China and India).

But number two? It’s not heavy industry, it’s not agriculture, it’s not even aviation – it’s SUVs.

In the last eight years, electric cars have saved approximately 100,000 oil barrels per day, and improvements in the fuel economy of smaller cars have saved another two million barrels per day. But the rise of the SUV has caused a gigantic increase of 3.3 million oil barrels per day.

Once a niche vehicle for people who wanted to drive across rough terrain, the SUV has now become a mass-produced item the moneyed class uses to drive to Bikram yoga. In 2010, there were 30 million SUVs worldwide. Now, there are more than 200 million. To put that in context: there are only 5.1 million electric cars worldwide.

Cars now use much lighter materials than they used to (less steel, more aluminium), they’re built from one piece of metal, they often have front-wheel drive, their motors use four instead of eight cylinders, and so on. But all the weight saved by these technological advances is cancelled out by heavier design.

Who’s got the biggest ... SUV?

Why do people love driving these massive SUVs? It’s obviously very luxurious sitting high up on your SUV throne, looking down on all those toy cars on the road, with more legroom than you get in business class, and a trunk that can fit a six-month-old hippo. But the appeal goes beyond comfort and convenience.

It’s a question of size: who’s got the biggest? Every year, the driver’s seat creeps up. Other drivers are up higher, so you have to go higher, which means they go even higher, and so on and so forth. With every SUV purchase, someone is dumping a feeling of insecurity into someone else’s lap. And so SUVs beget more SUVs.

In the United States, you are about 47% more likely to be killed in a car crash if you’re hit by a vehicle that’s 450kg (992lb) heavier than yours (like a Toyota Corolla being hit by a Jeep Wrangler).

Economists call this an “externality”, a cost that ends up on someone else’s plate. In this case, it’s a decrease in traffic safety thanks to more and more heavy cars. And what does that cost? If you want to slap a price tag on a human life, US economists estimate that the increased number of traffic fatalities due to vehicle weight gain in the United States cost about $93bn per year.

So why did car makers start manufacturing SUVs in the first place?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the SUV is a US invention, where bigger has always meant better.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the SUV is a US invention, where bigger has always meant better. Low fuel excise taxes compared to the rest of the world mean that fuel economy is not a big concern of US car buyers. Still, it wasn’t until sometime in the 1980s that pickup trucks, SUVs and minivans became all the rage, thanks to a series of unfortunate decisions by US policymakers.

It all started with a petty battle in an even pettier trade war. In the 60s, France and West Germany limited the import of US frozen chicken, which prompted Lyndon B Johnson, the former US president, to hit back with the so-called “chicken tax” on the import of potato starch, brandy, and “light trucks”.

At the time, light trucks – SUVs, pickup trucks and minivans – only accounted for a small portion of the US car market. There weren’t many foreign car manufacturers who made these light trucks, which is why they ended up on the same list as potato starch and brandy. An import tariff on light trucks was little more than a light slap on the wrist.

Even so, the tariff had big consequences. The chicken tax, although weakened, has lasted until today. While US manufacturers had to compete with foreign carmakers in the market for smaller vehicles, they had less competition when it came to manufacturing pickup trucks, SUVs and minivans. The market was theirs, which made it very much worth their while to make heavier automobiles.

How the SUV became popular

The SUV would never have become so popular without the countless exceptions that have snuck into US law throughout the years.

In the 70s, there was mass panic when the price of oil suddenly shot up by 400%. The Middle East was embroiled in conflict, and the US was slapped with an oil embargo by a cartel of big oil-producing countries because of its military support of Israel. Suddenly, politicians and consumers alike were worried about the fuel consumption of US cars.

In 1973, US Congress passed a law that required all car manufacturers to cut back on fuel consumption: the Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards. The fuel consumption of US cars fell at a breakneck pace. And US cars shed about 400kg (882lb) of weight in fewer than five years.

However, the law contained an exception for light trucks, or “automobiles which are not passenger automobiles’, as they were called by lawmakers. These were utilitarian, work-related vehicles for plumbers and farmers, and it was argued it wouldn’t be fair to treat them like normal passenger cars. That’s why light trucks weren’t required to save anywhere near as much on fuel consumption.

In 1978, amid new panic over the conflict in the Middle East, US Congress decided to introduce a “gas guzzler tax” – a tax on the sales of fuel-inefficient vehicles. Here, too, an exception was built in for light trucks.

By the 80s, the US fight against fuel consumption had already ended. Ronald Reagan, the former US president, froze the fuel efficiency standards, and there was no improvement in the fuel consumption of US cars for nearly two decades.

The victor, ironically enough, of a decade of US fuel regulation was the gas-guzzling SUV.

Europe doesn’t believe in fat shaming chunky cars

It’s not just the US, though. The European Union (EU), Japan, China – nearly every country has rules to curb the emission of greenhouse gases by cars. And yet, the regulations for greenhouse gas emissions are often designed in such a way that the manufacturing of heavy cars isn’t discouraged – in fact, quite the contrary.

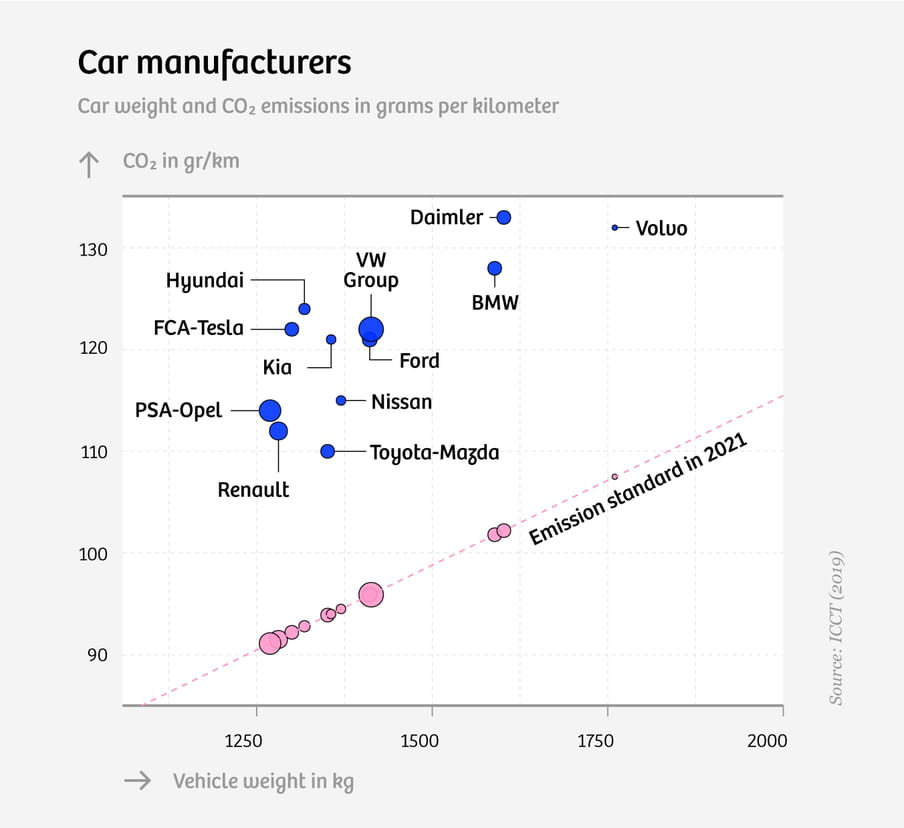

In the US, there is a separate category for “light duty trucks”. But the EU – which has just about the strictest emission standards worldwide – does not discourage SUVs, either. By 2021, all new passenger cars in Europe must meet an average emission target of 95 grams of CO₂ per kilometre. But CO₂ emissions per kilometre have been increasing for the past three years. The sector will have to go to extreme lengths to meet this target: analysts are predicting that car manufacturers will be faced with paying billions in penalties.

But still, the sale of SUVs is increasing, even in Europe. Why?

During the 90s, the European commission made frantic attempts to set emission standards for cars. At the time, they reached a deadlock because of conflicting interests between member states. If Europe were to hold all car manufacturers to the same CO₂ standards, countries that predominantly made heavy cars (Germany) would run into difficulties, while those that made lighter cars (Italy and France) would have it easy.

So Germany was dead set against one-size-fits-all CO₂ standards. The Germans argued that Europe shouldn’t be fat shaming chunky cars. If consumers wanted great big SUVs, they should be allowed to have them.

In the end, the Germans got their way. Since 2009, Europe’s emission targets have been based on weight: the heavier the car, the more CO₂ it may emit. In practice, this means that if a manufacturer makes a car 100kg (220lb) heavier, that car can emit 3.33 more grams per kilometre. And the reverse also holds: if a manufacturer makes the car 100kg lighter, then it must emit 3.33 grams fewer.

This means that each car manufacturer has its own emission target. The PSA Group (the French company that makes Peugeot, Citroën and Opel cars) has an emission target of 91.1 grams of CO₂/km because of their relatively light cars, while Volvo’s target is 107.5 grams per kilometre because of their heavier cars.

Should Peugeot discover some fancy new material that could make cars much lighter, then that would be good for CO₂ emissions, but not for emission targets. If Peugeots weigh less on average, they will also be held to stricter emission targets. So Peugeot has little incentive to look for ways to make their cars lighter.

But it gets worse. Research by the International Council on Clean Transportation shows that manufacturers are becoming better and better at lowering the emissions of heavier vehicles. Soon they will reach the point where they can make a car 100kg (220lb) heavier without it emitting an extra 3.33 grams of CO₂. Once that’s the case, it will be easier to meet emission targets by increasing vehicle weight, thus increasing CO₂ emissions!

Why aren’t we feeling SUV shame?

Meanwhile, in the US, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed to freeze fuel economy standards for all passenger cars once again. That prompted the state of California to use its authority under the Clean Air Act to write its own sort-of-kind-of fuel economy rules – to the dismay of carmakers, which now have to deal with different rules in different states.

So some of them decided to make a deal with California: we’ll follow your rules for the whole of the country if you promise not to make any new ones. The deal triggered multiple Twitter meltdowns by president Donald Trump; the EPA revoked California’s waiver under the Clean Air Act; and the Justice Department launched an antitrust suit against the automakers because of their Californian conspiracy to make all cars more fuel efficient.

So substantial progress on car emissions, let alone car weight reduction, in the US is probably idle hope.

Right after the second world war, European car manufacturers still made those funny dwarf cars. Imagine a Kleenex tissue box on wheels

In Europe, on the other hand, there are moves to make better laws. In 2021, the European commission will consider proposals to regulate according to vehicle footprint (car size in square metres) instead of weight (car size in kilos). That would already be an improvement because it would create an incentive to make cars lighter.

But that’s actually still pretty tame. Why shouldn’t we promote driving lighter cars? Do we really need to transport ourselves in gas guzzlers with the air resistance of a slurry tanker? Why aren’t we feeling SUV shame?

Right after the second world war, European car manufacturers still made those funny dwarf cars. Imagine a Kleenex tissue box on wheels that just about fit two passengers and some shopping. Take the BMW Isetta (1955), which weighed 330kg (728lb) and had a fuel consumption of 3 litres per 100 kilometres. Incredibly efficient for those days. Regular cars weighed next to nothing then too. Citroën’s iconic 2CV? 550kg (1,213lb).

Is it impossible to make cars so light nowadays? Of course, safety regulations have become more stringent, and modern cars are full of fancy devices – tiny motors that open windows, that sort of thing. Even so, they could easily be a lot lighter: a recent electric incarnation of that same BMW Isetta still only weighs 500kg (1,102lb), and that’s including a heavy battery.

In any case, we can easily manage with far fewer SUVs on the roads. Not that we should ban SUVs, but we could at least make them shockingly expensive. The Netherlands, my home country, has a good approach: we have a high fuel tax, and there’s also a tax on the purchase of cars with high CO₂ emissions. As a result, cars here are already about 100kg (220lb) lighter than the European average, or about 700kg (1,543lb) lighter than in the US.

But it is much more important for Europe to stop basing emission norms on vehicle size and weight, and instead start regulating based on what actually matters: CO₂ emissions per kilometre.

So yes, let’s start fat shaming those SUVs.

This piece first appeared on De Correspondent. It was translated from the Dutch by Hannah Kousbroek.

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Dig deeper

Thanks to this landmark court ruling, climate action is now inseparable from human rights

The Dutch supreme court has ruled that the state must reduce its CO2 emissions. The impact will be felt around the world.

Thanks to this landmark court ruling, climate action is now inseparable from human rights

The Dutch supreme court has ruled that the state must reduce its CO2 emissions. The impact will be felt around the world.