At its simplest, a border is the line between us and them. Take, for example, the short history of the Republic of Biafra in eastern Nigeria. On 30 May 1967, General Odumegwu Ojukwu declared secession from the federal government in Lagos, the Nigerian capital at the time. Biafra was established as a sovereign nation beneath a jagged line that ran about 200km to the west of Owerri, a town widely considered the heart of Igbo land. The line followed the Niger river northward for another few hundred kilometres, then undulated eastwards past Enugu and Ogoja to neighbouring Cameroon.

About six weeks after the secession, on 6 July, the Nigerian government rejected Ojukwu’s new border with a declaration of war. The Nigeria-Biafra war lasted for two and a half years, until January 1970. An estimated 100,000 combatants were killed, and as many as two million Biafrans died of starvation. When Biafra conceded defeat, the Nigerian government restored the borders assigned by colonial powers in 1914.

The ubiquity of national borders has made them an essential tool for understanding and navigating the modern world. They are invariably difficult to change. Most of us cannot imagine life without them. Today, borders are a means to define the limits of the global social order. Nonetheless, they are a recent invention.

Today’s borders are colonial leftovers

Across Africa, South America and many parts of Asia, today’s nation states are the legacy of colonial-era agreements and negotiations between European powers. Before them, the indigenous kingdoms, cities and peoples had developed various logics for establishing their claims to land, defining their relationships to one another, and plotting boundaries for their communities.

Some erected walls for this purpose, such as the Benin Kingdom or Old Delhi. Others relied on geography and geology. The Incan Empire, for example, reached from the coast to the mountain ranges of the Andes. These territorial limits were irrevocably altered by Europe’s economic expansion.

The form and function of territorial borders were determined largely by the governments of Belgium, Britain, France, Portugal, Spain and other colonists. Their pursuit of land, harvests, rubber, metals, minerals and other resources fuelled an infamous scramble to claim distant territories mapped with contextually arbitrary lines.

At the Berlin Conference of 1884-5, European bureaucrats determined the precursors of most of the national borders which define Africa today. A treaty drafted by colonial powers, meeting to decide the fate of Belgian King Leopold II’s predatory ambitions in Congo, agreed on three distinct spheres of interest for European claims in Africa.

First, "That of the commercial and industrial nations, which a common necessity compels to the research of new outlets." Second, "That of the States and of the Powers summoned to exercise over the regions of the Congo an authority which will have burdens corresponding to their rights." Third came the peoples of Africa, "And, lastly, that which some generous voices have already commended to your solicitude – the interests of the native populations."

Borders derive meaning not just from the fact of their existence but from the motives behind the division – the how and the why. As first conceived, the lines mapped by colonial powers did not significantly alter or interfere with boundaries set by indigenous communities and kingdoms. Rather than delineate nation states, as they do today, the lines of the colonial map served primarily as a barrier to entry for rival powers.

Our contemporary understanding of national borders is inextricably linked to this Eurocentric idea of exclusive colonial possession. Other settlements between European powers included the Sykes-Picot Agreement in the Middle East and the Treaty of Tordesillas in South America. Their treaties ignored the socio-political entities that already existed in these regions, imposing new borders and dividing communities along lines that often made sense only to the Europeans.

As Lord Salisbury, British prime minister at the time, commented of the Berlin Conference: “We have been giving away mountains and rivers and lakes to each other, only hindered by the small impediments that we never knew where the mountains and rivers and lakes were.”

As the colonial project advanced inland, its administrative apparatus evolved. The European presence depended on foreign ideas of social organisation, underpinned by both economic and military power. Disparate groups were cobbled together under colonial protectorates and administrative regions. “Where borders are drawn, power is exercised,” says Dieter Lamping, professor of comparative literature at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz.

Over time, regions subjected to colonisation were grouped into countries. In the entity which from 1914 became known as Nigeria, for example, the lands of the Igbo, Isoko and Idoma nations were lumped together with other ethnic groups and empires. “Nigerians” were fashioned from hundreds of such communities, including the Egba, Ijebu and Yoruba peoples from Oyo, Ife and other south-western regions. To the north, the new nation state spanned the territory of the Nupe, Nok and Kanuri, a few Hausa caliphates and sultanates, some grazing lands held by the largely itinerant Fulani people, and more.

Borders decide who has the right to travel the world

By the 1960s, when Biafra attempted to establish itself as an independent territory, national borders had long been a political fact. The secession in 1967 was an attempt by Igbo people – along with the Itsekiri, Efik, Ijaw and other nations – to renegotiate the terms of the Nigerian state. They rejected the new name, new flag and new political identity imposed by the annexation and amalgamation of disparate parts of West Africa. Their challenge to this Eurocentric ordering of the world failed.

National borders had become largely inflexible, their parameters fixed in the popular and political imagination. As the world moved on, entering new cycles of cold war, economic crises and globalisation, old borders were assigned a new purpose. Where once they defined the boundaries of sovereign states, borders began to function as tools for regulating human mobility.

This new iteration in the old concept of border integrity manifests a familiar imbalance of political power. Today’s borders work along the same ideological lines which made it conceivable for European colonists to annex the planet, by imposing arbitrary geopolitical boundaries on hugely diverse indigenous societies. Contemporary borders mark the limits of the other: they function as sites of exclusion for anyone deemed unworthy to traverse the planet at will.

And so we get the modern concept of migration.

Today’s "crisis of migration" – an idea which has gripped the public imagination – is merely a term for the uneasy reaction of settler-colonial states to transnational or transcontinental movements of people whose place in the world is supposed to be fixed. Those who are deemed migrants are often travelling in the same direction as the capital and other resources which have flowed from Asia, Africa or South America to the global north.

In response, border authorities in the European Union, United States of America, and Australia are ramping up their attempts to regulate, restrict or completely inhibit such human movement. In these spaces, borders are not just “the formal political division line between territorial units”, defined by Indiana University professor of political science Gabriel Popescu. They become an indispensable barrier to separate people who are deemed to have a right to travel the world from people who are not.

Pivot points in a contest of unequal powers

The migration crisis is a product of our time – even the terminology is new. In an essay exploring identity, James Wan highlights that until the 1900s, "migration" described the movement of birds, not humans. Investigating the origin of the modern usage of the word "(im)migrant", William Germano cites a 1922 Sydney edition of the Daily Mail. Arrivals to Australia from Britain, the newspaper stated, should not be called immigrants but rather migrants, “because to go from Britain to Australia is only to pass from one part of Great Britain to another”.

In other words, the language we use to describe movements of people from one place to the other has become politicised, just like borders themselves. The discourse implies a hierarchy of states, according to their desirability. The desired nations of the 21st century protect and enforce this hierarchy, through hostility, violence, and even death.

For millions of people, the possibility of transcontinental travel is pre-determined by Euro-colonial notions of citizenship or nationality. All over the world, this has inescapable implications for contemporary human movement. Borders determine who can go where, and how much indignity or suffering is involved in the process.

Legal or not, the concept of transnational or intercontinental "migration" – and simultaneously, the status of the "migrant" – tracks the same disempowering lines that enabled colonisation. This is why the violence that accompanied colonisation and the imposition of Eurocentric political identities on the rest of the world remains present at borders today.

For most of human history, the notion of large numbers of people dying as a direct result of their desire to travel from one place to another would be incomprehensible. Yet today, this is an everyday phenomenon, often resulting from anti-immigration policy decisions. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, an estimated 3,000 people died in the Mediterranean sea in 2017, during attempts to reach Europe. At the US-Mexico border, 412 deaths were recorded in the same year.

Nationals of countries in the global south who attempt to travel legally are forced to pay significant sums of money for the privilege of being interrogated, mined for sensitive personal information, and put through the bureaucratic wringer in hopes of being authorised to cross borders. Those who are unable to successfully navigate the legal migration system have little choice but to turn to gruelling and dehumanising alternatives.

Death, as anthropologist Jason de León showed in his debut work of nonfiction, is an inevitable and sometimes deliberate outcome of the border protection policies designed to keep humans out. Yet, as tobacco sellers and the agencies which regulate their advertisements can tell you for free, the possibility of death fails as a deterrent in the face of strong human desire.

In The Land of Open Graves, De León uncovers the lives and stories of clandestine migrants on the US-Mexico border. Many have quietly crossed the border multiple times. For them, even this most formidable obstacle merely represents a hurdle, which, with adequate planning, can be scaled. They are not wrong. De León cites studies to show that despite decades of policing and billions of dollars invested in border security, up to 98% of clandestine migration attempts are successful.

Borders are a new idea

Like a KEEP OUT sign on the bedroom door of an angsty adolescent, the real work of borders is mostly psychological. But unlike the closed bedroom door, the damage to those who would enter is all too real and the costs unacceptably high.

People who desire to move to new countries for long periods tend to share similar aspirations. They hope for a better life – safety, work, often both – with better outcomes for their families. For many, eventually returning to their first country is integral to their plans. Border hostilities and anti-migrant sentiments diminish such realities, reducing such people to mere caricatures of danger or otherness.

Long-term travellers who are unwelcome in their host nations are vilified for any reluctance to abandon their cultures in the same way that they abandoned their countries. In the legal and justice systems they are likely to be criminalised, profiled or targeted. Their contributions to the progress of the nations they settle in are routinely devalued. Their labour is exploited. Any failure of respectability on the part of one is treated as an indictment of all.

Many nation states today are the result of borders created without regard for the people whose lives they now define. Modern borders are now being policed with this same disregard. The idea that transnational movement can be significantly impeded by border control, visa regimes and "legal migration" is legitimate – up to a point. Access to sovereign states can be governed by migration laws and other policies, but the effectiveness of such structures is limited.

Borders are not immutable. In the bigger global-historical scheme of things, they are still new. Again and again they fail. The only thing that hostile geopolitical boundaries can achieve with any consistency is the dehumanisation of all those who interact with them.

One of our Nigerian readers, Editi Effiòng, who would have been Biafran if Ojukwu had won the war, responded to my first article for The Correspondent. He posted: “I just realised I have always looked at earth-from-space photos, seeing map lines in my mind. But those lines don’t exist.”

He was right.

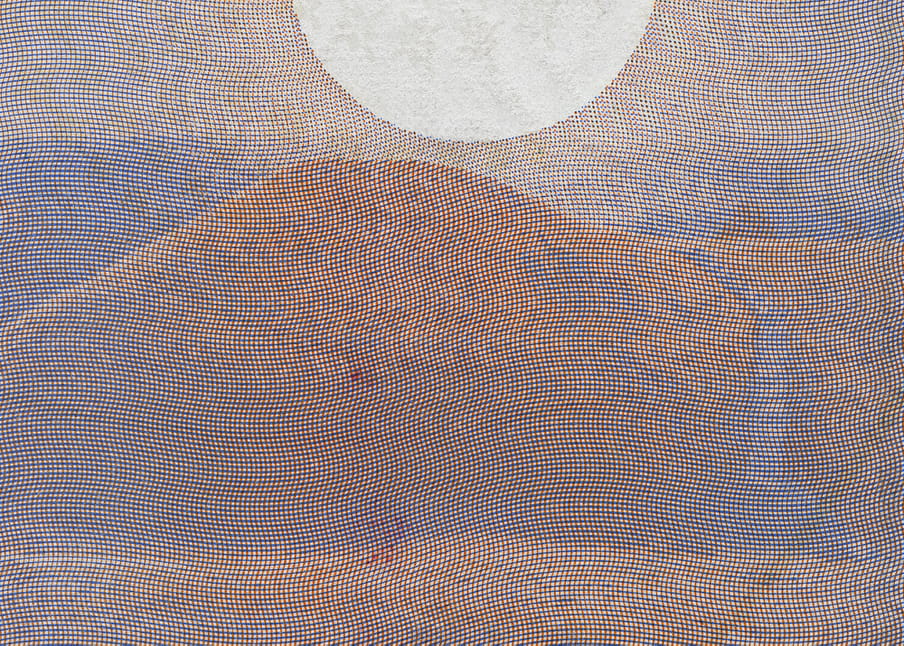

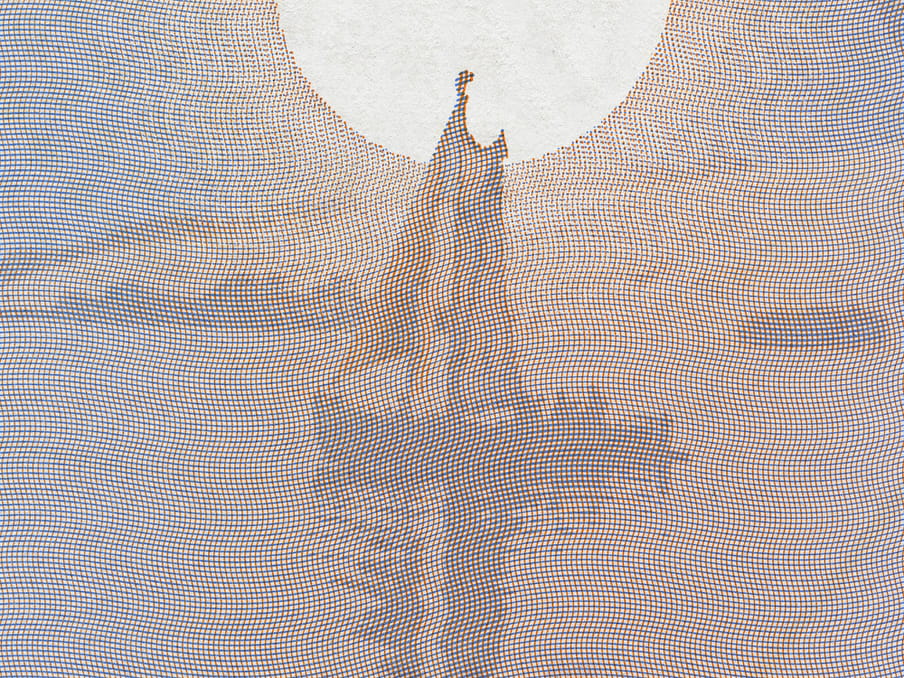

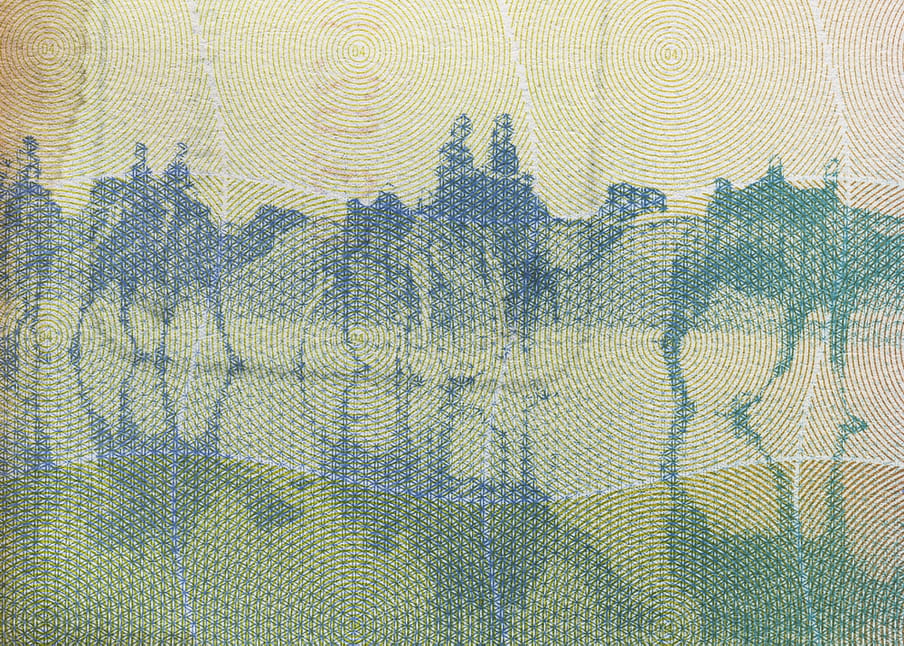

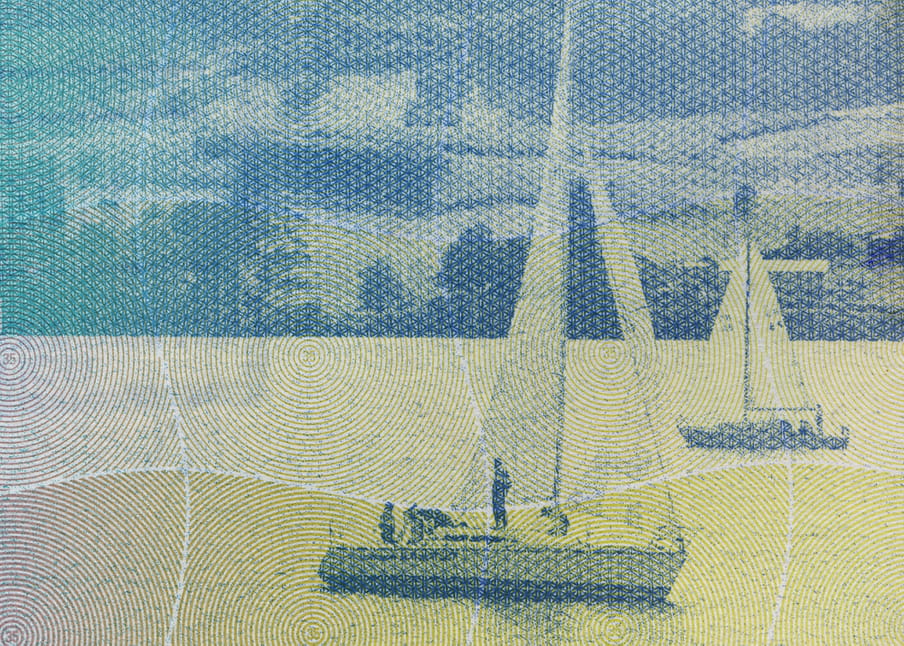

About the images

I had never taken a good look at own my passport before I first saw the series Landscape of Authority by Finnish visual artist Karl Ketamo. The work shows close-up crops of several different passports, cleverly pointing out the juxtaposition of symbols referring to both national identity and migration. The recognisable, formal pattern of the passport rests on top of all the images – almost like a prison grid. Given the nature of the object and its function, this contradictory aesthetic is able to visualise the power structures and politics regarding the movement of people painfully well. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

I had never taken a good look at own my passport before I first saw the series Landscape of Authority by Finnish visual artist Karl Ketamo. The work shows close-up crops of several different passports, cleverly pointing out the juxtaposition of symbols referring to both national identity and migration. The recognisable, formal pattern of the passport rests on top of all the images – almost like a prison grid. Given the nature of the object and its function, this contradictory aesthetic is able to visualise the power structures and politics regarding the movement of people painfully well. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)