Great news! We’re a lot less alone than we think.

Since ancient times, humanity has looked at life through a hierarchical lens, with men on top. Evolution produced a staggering array of amazing forms of life, and then there’s us, the absolute pinnacle, all the way up there all alone. After all, we make tools, plan ahead. We have consciousness, culture, language, morality. We feel pain, we invented the iPhone.

But that’s just not how it is. Advancing scientific insight leaves us fewer and fewer “unique human qualities”. Apes plan, too – they gather stones to crack open nuts they haven’t found yet. Crustaceans feel pain, too – they learn from it, they care for their wounds. Parrots also have language – they name their chicks, tell each other where to get the best fruit. And when in cages, they come up with new words in human lingo.

Like “yummy bread” for cake.

For the longest time, each new discovery like this took us by surprise. But nowadays, biologists just think: makes sense. Because where we once saw evolution as a mad artist, spewing out completely new forms of life endlessly and at random, it is becoming increasingly clear that evolution is also something else: a handyman coming up with similar solutions to similar problems. That’s why species which are completely unrelated genetically can turn out to have much more in common than we thought.

We call this phenomenon “convergent evolution”. Evolutionary branches moving towards each other.

Take the human and the octopus. On the face of it, two completely different animals. What could we possibly have in common? Well, our eyeballs. They’re really similar – practically identical, in fact. The same solution to the problem of “needing to know where you are”. Despite the fact that our last common ancestor 550 million years ago was swimming around without anything we would call eyes. The octopus eye is even better than ours; it lacks a blind spot.

(And anyone who saw the Netflix documentary My Octopus Teacher will wonder if octopuses might have a human capacity for friendship, too.)

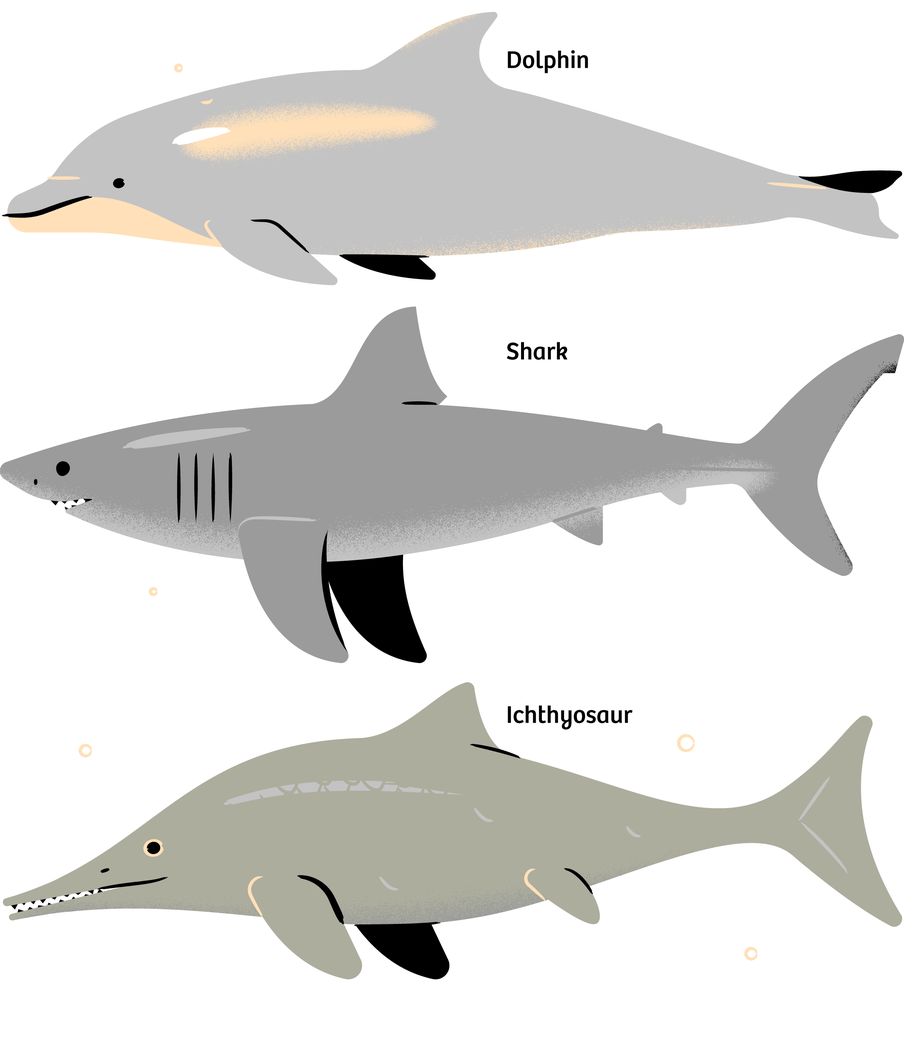

Then there are extremely divergent branches on the evolutionary tree that don’t just converge on eyeball design, but in total. Consider the dolphin, the shark, and the ichthyosaurus.

The first is a mammal, the second is a fish and the third is a reptile. Still these three different branches of the evolutionary tree end up at the same streamlined body design: a torpedo shape with a dorsal fin, two flippers and a powerful tail. All three are found in the same evolutionary niche: fast-moving marine predator.

You also see convergence in how organisms “think” about things. The mud dauber, termite, cliff swallow and us all discovered the arch as a fundamental building component of natural stone cottages. Termites even have agriculture. They grew edible moulds inside their mounds tens of millions of years before we did. Leafcutter ants even use chemical pesticides while at it.

Species can evolve towards each other in every aspect of their biology, in appearance and behaviour. Seen like this, there is no such thing as “more or less evolved”, but only “optimal solutions to problems the environment poses”.

I’m like a bird

I now see each animal as an ingenious sum of beautiful finds. That might sound calculating, but it opens the door to a new sense of kinship: suddenly, you can have so much in common with so many more living things than just the same old mammals that are genetically your closest relatives.

After all: the mud dauber thought the arch was pretty brilliant too. Better yet, in some aspects humans are more like animals who are 340 million years of evolutionary history apart from us than like the genetically nearly identical great ape.

Looking at abilities like tool use or language, you quickly find how certain birds, like crows and parrots, can run rings around what a primate can do. The kea, for example, understands probabilities. And parakeets have brain structures dealing with language processing that apes don’t have. “I think few people realise that in many respects we are more similar to birds than we are to apes,” a bird biologist once told me.

Consider the yellow-naped amazons in Costa Rica. Different parrot populations communicate with each other in different dialects. Young birds placed in a new population – “immigrants” – pick up a new dialect much faster than older birds, who either can’t keep up or just can’t be bothered.

Result: no integration in the new parrot group.

Sound familiar?

Coincidence or not?

But how exactly does convergent evolution work?

And if evolution is prone to end up at optimal solutions for specific problems, and only a limited amount of solutions is really worthwhile – does that make evolution predictable? Can we know where it’s going?

Evolutionary biology concerns itself with monumental questions, such as: why does life take the forms that it does? How do species adjust to their environment? Or how does one species change into many different species?

Just a few changes to the DNA in your cell nuclei, and suddenly you wouldn’t be a human (read: watery meatbag that converts endless staring at Google Docs into salary), but, for instance, a white fluffball that converts insects into white feathers – a long-tailed tit. Even though tracing both human and bird back 340 million years will show you they once were the same thing: a kind of tetrapod (four-footed vertebrate) called an amniote: our common ancestor. It’s bizarre to think about.

But defining exactly what role a phenomenon like convergent evolution plays in the great emergence of species is a topic that gets biologists’ feathers ruffled. There are two distinct schools of thought: one believes in coincidence; the other, not so much.

Let’s take the emergence of humankind as an example. Those who believe in coincidence think that our existence on the Earth today all goes back to a five-centimetre-long aquatic worm that had a primitive notochord (something like a proof-of-concept backbone), which lived 535 million years ago: the early ancestor of all vertebrates, Pikaia gracilens.

What luck, they argue, that nothing like a meteorite, rampant algae bloom or sudden El Niño wiped out little Pikaia before its time. That’s why we’re here: what a coincidence. The same way all life owes its existence to coincidence. Arose by coincidence, and stayed alive by coincidence.

Because of the huge role that coincidence plays, the variations in life forms that evolution can produce are endless

Because of the huge role that coincidence plays, the variations in life forms that evolution can produce are endless. Rewind the tape of evolution again and again, and you’ll never get the same result twice. In other words: without Pikaia, there’d be no vertebrates and no human beings – but there’d be other curious creatures.

The other school is less mad about coincidence. They believe there are limits to diversity. Life is only as diverse as there are ecological niches to fill, or: problems to solve. This group of biologists thinks that “evolution” is fairly predictable, the handymen will often come up with similar solutions to similar problems. Species that live in a similar environment evolve similar features: convergence.

As far as people are concerned, evidently there was a niche for some kind of biped with two hands, a flat face, a short neck and a big brain. If the mammals hadn’t filled this niche with Homo sapiens, the reptiles would have jumped on it (or as a biologist would say: evolved into a “dinosauroid”).

In recent years, the evolutionary biologists of this latter school have been drawing more and more unexpected connections between quite diverse animal species.

Evolution steals its own ideas

No biologist denies that convergent evolution exists. All kinds of animals evolved all kinds of eyes. Mammal, bird and insect all came with their own wing design. Likewise, mammals, birds and the bumblebee all ended up being “warm-blooded”, in order to survive the cold (that’s why bumblebees are fuzzy: it helps keep the warmth in).

The discussion between the two camps is really about how big a role convergent evolution actually plays. Team “There Is No Coincidence” likes to throw the following anecdote into the debate: mammals in Australia.

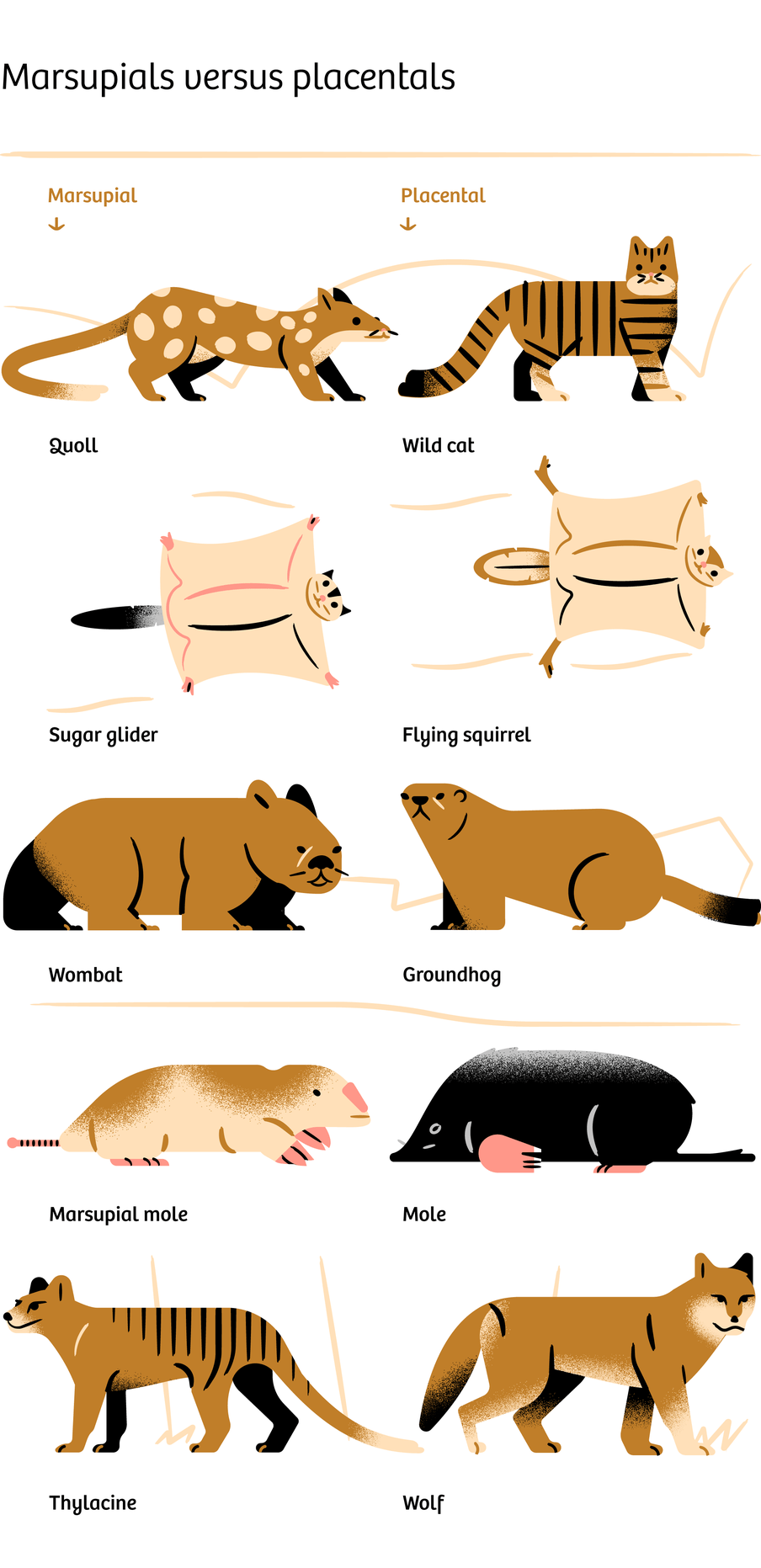

After the dinosaurs died out, mammals took over the land. Almost every part of the world got mammals that carry their offspring in the uterus: the “placentals”. But not Australia. That’s where you get marsupials: also mammals, but not with one uterus – they actually have two, the second one being an external one, the pouch.

Despite this, the placentals and the marsupials, completely independently, went on to evolve into a whole bunch of mammals with a lot of common behaviours and features.

Both produced some kind of “mole”. Both came up with a flying squirrel. Team Placenta has the groundhog, while Team Marsupial has the wombat. Team Placenta gave us the cat, but check out what Team Marsupial’s got – the quoll, which they say makes just as good of a pet.

But the top-of-the-line marsupial is unquestionably their answer to our wolf, the Tasmanian tiger, also an apex predator. See how dog-like they are on YouTube. Unfortunately they were exterminated a century ago by Tasmanian settlers. The last Tasmanian tiger died of malnourishment in 1936, in a forgotten corner of an Australian zoo.

Evolution in the fast lane

But are these the rare exceptions that prove the rule of evolutionary randomness, or not?

Thanks in part to the rise of affordable DNA sequencing, we can better trace the evolutionary history of animals. And? A lot of animals scientists thought were close genetic relatives because of similarities in appearance and behaviour actually aren’t.

Then, team No Coincidence has even begun to experiment with evolution. One such experiment showed how male guppies evolve extravagant colouration to impress females, but only when there are no predators near. Introduce predators to their ponds, and the males go dull again.

Darwin would have been gobsmacked. He saw evolution as an extremely slow process playing out over millions of years. But we’ve long known that evolution can suddenly kick into high gear – there’s plenty of everyday examples. Rats that develop resistance to rat poison? Insects that develop a resistance to insecticide? Antibiotic-resistant bacteria? That’s all evolution, too.

And now yet another amazing opportunity to watch evolution in real time is emerging.

Darwin comes to town

The urbanisation of the planet is unstoppable. Thousands of cities currently occupy some 3% of the world’s land area in total. So of course all kinds of animals are rapidly adapting to human structures.

One funny example in the Netherlands is that city snail shells are becoming lighter in colour. Why? Cities are warm places, and dark shells retain a lot of extra heat from the sun – too much so. So from north to south, urban snails are turning pale.

Meanwhile, in the UK, biologists discovered this year that closer contact with humans has led to self-domestication among urban foxes. They are becoming more tame, with shorter snouts, smaller brains and increasingly stronger jaws to help them crush our assortment of rubbish.

City animals are also becoming smarter. “Cities require advanced problem-solving, and that’s what we are often seeing emerging in urban wildlife,” says evolutionary biologist Menno Schilthuizen, author of Darwin Comes to Town: How the Urban Jungle Drives Evolution. Think of raccoons becoming masters at breaking open even our most secure “animal-proof” rubbish bins. All kinds of animals are learning to use their front paws as “hands”.

Then, the parrots have discovered urban living. Makes sense, given that in the Amazon parrots travel great distances, are excellent navigators, have great memories, and form social groups – all things that promote development of a larger brain, and all things that help you get by in the city.

It’s not unlikely the animals around us will keep getting more and more “human”.

Of course, the streets won’t suddenly be overrun with animals transitioning to a “human” shape. Even if they’ll become slightly more human. (Pray that the champion of window crashing, the Eurasian woodcock, starts evolving forward-facing eyes.)

So wouldn’t it be nice to not view World Animal Day as pet day, or “how-much-DNA-do-we-share day", or “do-we-have-a-recent-common-ancestor day”. But a day on which you look at the life around you and ask:

What problems does this creature face in life?

And: to what extent does it solve them the way I would?

Maybe in some respects, you and that long-tailed tit are floundering through life in much the same way.

Translated from the Dutch by Kyle Wohlmut.

Dig deeper

98% of all animal species on Earth have a PR problem. That’s bad news for everyone

Insects do all the dirty work. They process faeces and decompose corpses. Plus they pollinate flowers. In spite of this, their image sucks. We need to change that. Because a dramatic decline in invertebrates threatens the liveability of this green planet.

98% of all animal species on Earth have a PR problem. That’s bad news for everyone

Insects do all the dirty work. They process faeces and decompose corpses. Plus they pollinate flowers. In spite of this, their image sucks. We need to change that. Because a dramatic decline in invertebrates threatens the liveability of this green planet.