Two point six trillion dollars

(with a t).

That’s how much untaxed profit American companies are thought to have stashed away in tax havens abroad.

“I believe it could be anywhere from $4 trillion to $5 trillion outside,” Donald Trump guesstimates. “You know, don’t forget we’ve been talking about $2.5 trillion for four years now. [...] Well, you know, it grows. I think it… I wouldn’t be surprised if it was $5 trillion but, you know,

we’re close.”

Two trillion, five trillion: with numbers this big, who’s sweating the fine print? In any case, companies won’t willingly repatriate it. “Number one, the tax is too high,” Trump explained in that same interview with The Economist. Multinationals currently have to pay 35% of their foreign billions to the American IRS when they bring them back into the country. “We’re letting that money come back in. [...] We’re going to make it 10%.”

The land of tulips and windmills, the home of the International Criminal Court, and the number-one tax haven for American multinationals

That means that in the coming years, trillions of dollars will likely flow back into the US. But most of that money won’t be coming from Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Singapore, or Switzerland. It’ll be coming from an unassuming little country on the North Sea.

That’s right: the Netherlands. The land of tulips and windmills, the home of the International Criminal Court, and the number-one tax haven for American multinationals.

This is a story about a joint venture between the American and Dutch governments that, by creating loopholes in tax laws, made it possible for US companies to avoid paying tax by the score.

And if Trump has his way, they’ll get away with it, too.

How in the world did the Netherlands turn into a tax haven?

It’s April 2009 when a newly inaugurated Barack Obama announces a plan to fight tax avoidance. For the occasion he’s drafted a list of notorious tax havens: Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Switzerland, the Netherlands.

The Netherlands?

“An utter shock,” says Jan Kees de Jager, the Dutch state secretary for finance at the time. And “utterly undeserved,” adds his boss Wouter Bos, the minister of finance.

In the years that follow, Dutch politicians will continue to chant it like a mantra: the Netherlands is not a tax haven. In 2013, the Dutch House of Representatives will even pass a motion on it: stop using that “deleterious descriptor.” I mean, we all know the Netherlands is just an innocent way station for tax-averse companies headed for fiscally sunnier shores, don’t we?

Months of investigation, including the review of hundreds of pages of confidential policy documents, internal memos, and emails, reveal a very different picture. The Netherlands is the biggest tax haven in the world for American companies – bigger than the Cayman Islands, bigger than Switzerland, bigger even than Bermuda.

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

The two men in charge of the country’s tax policy may have seemed caught off guard by Obama’s list, but four years earlier their own Ministry of Finance had changed the rules in a way that enabled American companies to pay almost no tax on their foreign profits.

The Dutch parliament never posed any formal questions about this change, never conducted an inquiry, never requested an emergency debate. The change in question deletes paragraph 4 of article 24 in the NL-US tax treaty. That may sound as earth-shattering as paint drying on a summer’s day. But don’t be fooled: this move enabled American multinationals to avoid paying hundreds of billions of dollars in tax.

Tax avoidance, Dutch style: a primer

To understand how the Netherlands could become such a tax haven, you have to understand exactly what it is that American companies do here.

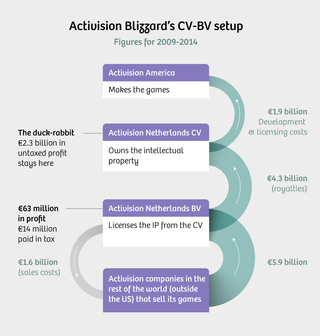

Take Activision Blizzard, known for such household-name games as Call of Duty, World of Warcraft, and Guitar Hero. Believe it or not, these blockbusters come to life in a basement on a tree-lined street in downtown Rotterdam! At least on paper they do. Here, you see, lies the headquarters of ATVI CV, an Activision Blizzard subsidiary nominally responsible for all the games the American company develops.

Here’s how it works. In theory, a company pays tax in the country where it’s incorporated. Now suppose a copy of Guitar Hero is sold in France. You’d expect the revenue to go to Activision in America; after all, that’s where the company that makes the game is located. So that’s where the profit should end up. In 2009, however, Activision assigned its intellectual property – that is, ownership of its games – to the Dutch-basement-dwelling ATVI CV.

The company lives in a fiscal no-man’s-land. It doesn’t pay tax anywhere

That’s how ATVI CV, a company with no employees whose management lives in Bermuda, was able to receive some €4.3 billion in royalties and turn a profit of €2.3 billion between 2009 and 2014. Profits on which Activision paid precisely zero in tax. (For comparison: a Dutch games company pays the standard 25.5% Dutch tax rate on profits.) Ironically, during that same five-year period Activision US wrote off another €141 million in tax for its R&D expenses. For games that – on paper – are “R&D’d” by a Dutch company.

All this is possible because the American and Dutch tax authorities see two different things when they look at a CV. The Dutch IRS says: that CV owes tax in the United States. The American IRS says: that CV owes tax in the Netherlands. The result: the company occupies a fiscal no-man’s-land. It doesn’t pay tax anywhere.

You might call it the duck-rabbit construction, named after the following drawing. One person sees a duck in this famous illustration; the other sees a rabbit. And you guessed it: the CV is the duck-rabbit of corporate entities.

But billions in profit for a company with no employees? Even for the Dutch IRS, that’s going too far. So you have to make sure your company has “substance”; something has to actually be taking place in the Netherlands. And so ATVI CV has a Dutch subsidiary: a limited liability company (or BV) that handles Activision’s international sales. The BV has forty-five employees.

Infographics by Leon de Korte, editorial designer at De Correspondent

Round one: the duck-rabbit goes down

Of course, the sixty-four-thousand-dollar question is: How did the duck-rabbit ever come about? Which Dutch politicians were behind it? How is it possible that the Netherlands has become one of the world’s top tax havens?

The story begins in 1995, when the American IRS accidentally makes the duck-rabbit possible by adopting a new rule. From then on, American companies can simply check a box: should my Dutch subsidiary be taxed in the Netherlands or in the US?

Duck-rabbit entities are just becoming popular when the Netherlands and America start negotiating changes to the US-NL tax treaty in 2002. At that time Wouter Bos is the state secretary for finance, and Bos is no fan of the duck-rabbit – he understands that it paves a superhighway to corporate tax avoidance. And so at Bos’s insistence, an anti-abuse clause is added to the treaty.

The clause’s message is simple: if the Netherlands and the US can’t agree on whether a company is a duck or a rabbit, then the company can expect a massive tax bill.

And the duck-rabbit is down for the count.

Down, but not out

But in May 2003 new elections throw Wouter Bos’s Labor Party out of the reigning coalition, and Joop Wijn takes over as state secretary for finance. And Wijn has a different take on things. This moderate politician, whose centrist party has vested all its hope in him, will play the starring role in the story of how the Netherlands became one of the biggest tax havens in the world.

The ball starts rolling soon after Wijn takes office, when he creates a stir in the American media. “In a barnstorming tour of the US that began Monday, Mr. Wijn, a 35-year-old former venture-capital executive at ABN Amro Holding NV, has been pitching the new Netherlands tax policy to dozens of American tax lawyers, accountants, and corporate tax directors,” The Wall Street Journal gushes about the new state secretary for finance.

Yet Wijn seems initially unmoved by a group of American tax advisers who lobby him to scrap the anti-abuse clause. “The argument is being advanced by a small group of tax consultants with a specific interest,” Wijn writes in a March 2005 letter to Dutch business journal Het Financieele Dagblad. “The treaty signals that contrived arrangements should not expect clemency.” Just like Bos, Wijn is acutely aware that scrapping the clause will lead to large-scale tax avoidance.

But then comes the U-turn. Bizarrely, Wijn suddenly decides in July 2005 that these same “contrived arrangements” are permissible. “To resolve the criticism coming from the tax consulting industry [...] it has been proposed that we unilaterally extend Dutch tax relief as if the treaty did not exist,” the Dutch director of international tax affairs notes in a policy memo. Wijn decides to hobble the anti-abuse clause.

Behind the scenes, however, that same director of international tax affairs is busy warning people of the immense consequences the decision will have. “This tax relief will enable American multinationals to enjoy an enormous and improper competitive advantage,” he writes. “As a result [the Netherlands] will be underwriting the takeover of its own business community by the American one.”

In the US they’re not as critical. “We are happy to have you guys give better treatment to our companies. If you would like to and can do so without it suggesting that we should do the same for your companies,” an official at the US Department of the Treasury writes to his counterparts at the Dutch Ministry of Finance.

In other words: Sure, help American companies avoid paying hundreds of billions of dollars in US tax if you want to – whatever you think is best.

What does the Dutch House of Representatives think about all this?

How does the Dutch House of Representatives react to Wijn’s decision to turn the Netherlands into a tax haven? The answer is simple: it doesn’t.

Not a peep of protest is heard from the Dutch parliament. On the contrary. The usual suspects on the left continue to decry tax avoidance (“Multinationals pay no taxes! It’s an outrage!”), but how exactly those companies get away with it – that, for example, article 24 paragraph 4 of the tax treaty is pretty crucial – well, that knowledge is missing in action.

Hybrid mismatches, tax treaties, anti-abuse clauses: it’s not exactly light reading. “It takes me half an hour to explain complex corporate structures like these to people,” says Jan Vleggeert, Associate Professor of international tax law at Leiden University.

You don’t have to pay tax in Bermuda, and thanks to the duck-rabbit you don’t pay in Holland, either

And so in just a few short years the Netherlands is able to turn itself into the number-one tax haven for American multinationals. You don’t have to pay tax in Bermuda, and thanks to the duck-rabbit you don’t pay in Holland, either. The big difference: the Netherlands doesn’t have the reputation of being a tax-evading pirates’ nest, the way Bermuda does.

And that disparity is entirely unjustified, because far more untaxed American profit hides out in the Netherlands than in Bermuda. Since 2005, nearly half a trillion (!) dollars in American profit has been safely stored in the Netherlands by companies such as Nike, General Electric, Heinz, Caterpillar, Time Warner, Foot Locker – the list goes on and on. Half a trillion dollars: it’s an unfathomable amount of money, nearly twice the country’s entire budget.

The American Chamber of Commerce estimates that “at least 80% of American investments in the Netherlands” run through a duck-rabbit. They don’t give hard numbers, but this certainly suggests that the vast majority of that half a trillion remains untaxed.

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

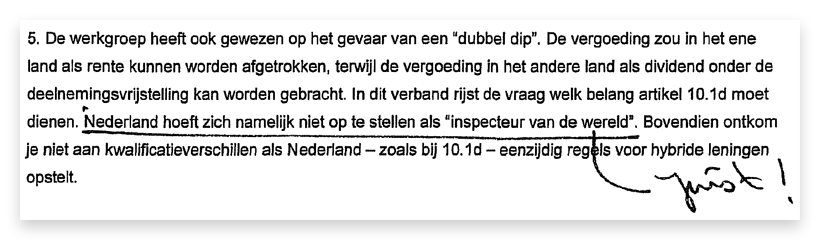

But the story doesn’t end there. Wijn continues to shower the business community – Dutch and American – with gifts. In 2006 he scraps another important anti-abuse clause, making the duck-rabbit loan possible. In an advisory memo, the director-general of tax affairs notes that the change will deprive foreign governments of tax income. Then again, he writes, “The Netherlands need not serve as the world’s [tax] inspector.” Wijn underlines the sentence and scribbles in the margin, “Precisely!”

From the document “Memo on streamlining anti-abuse clauses” (2006), obtained under the Dutch Freedom of Information Act (in Dutch only).

“Thanks so much! Yours truly, the AmCham”

In any case, the American business community is delighted with all of state secretary Wijn’s help. A year after his duck-rabbit decision, the American Chamber of Commerce presents him with an Investment Award for his “extraordinary contribution” to the Dutch business climate.

The American Chamber of Commerce is one of the most powerful lobby groups in the Netherlands, and that makes it a fixture in The Hague. AmCham parties are buzzing with Dutch political luminaries: current and former prime ministers, cabinet members, and party leaders.

Joop Wijn is – and will remain, even after he leaves politics – a sought-after guest at these festivities. Wijn attends the Grand Gala Ball (2007), the 50th Anniversary Gala Dinner (2012), the Annual Wine and Cheese Party (2013, 2014, 2015). He’s also on the board of the American European Community Association, a lobby group that provides “a neutral platform for senior business leaders and policy makers to meet and discuss a wide range of global policy issues.” To top it all off, his domestic partner, Patrick Mikkelsen, joins the AmCham in August 2012 as its executive director.

The AmCham also has strong ties with the Dutch civil service. An official at the Ministry of Finance doesn’t mince words in a March 2014 briefing before an upcoming meeting: “AmCham is a frequent contributor to the ministry’s discussions on tax matters,” he writes. “The ministry and the AmCham have a strong relationship at the civil service level.”

Several times a year, the state secretary for finance – whether it’s Wijn or his successor, Eric Wiebes – receives a delegation from the AmCham’s tax committee. The committee is populated by the tax directors of major American corporations: people like Arjan van der Linde (General Electric), René den Hartog (Nike), and – indeed – Activision Blizzard’s Alexander Hent. AmCham’s tax committee provides the ministry with detailed commentary on the most obscure fiscal issues, from “informal capital rulings” to “inbound discrimination clauses.”

Then the tide starts to turn

Yet even the AmCham can’t stop the international tide from starting to turn. Both the OECD and the European Commission launch projects to combat tax avoidance. And both organizations have the duck-rabbit in their crosshairs.

The Netherlands constantly throws a wrench in the works. When an EU working group proposes in 2012 to eliminate the duck-rabbit, the Netherlands says it has no problem with tackling European duck-rabbits. However, “extending the work to third countries [read: the United States] would be going too far.”

But tax avoidance is on the political agenda to stay. The Netherlands has to cede ground in the years that follow. “Internationally speaking, all eyes are trained [on us] and we can’t count on many allies,” writes the Dutch director of international tax affairs in January 2015.

This frustrates tax advisers to no end. They complain to the ministry about “the tone of the debate” and the “harsh and targeted demagoguery” of some House members and action groups. The state secretary for finance encourages tax advisers to “distinguish fact from fiction in the media” and to “provide a balancing voice in the often emotional debate on tax avoidance.”

But even state secretary Wiebes understands that doing nothing is no longer an option. “If the Netherlands were to block every measure that has a negative effect, it would isolate itself internationally,” ministry officials write.

RIP duck-rabbit (2005–2020)

So what can the ministry do?

In a meeting on June 4, 2015 ministry officials warn the AmCham’s president, Wouter Paardekooper, that the group’s beloved duck-rabbit is most likely going away. “We are very grateful to the ministry for the advance warning,” Paardekooper writes in a letter to the state secretary. “We are eager to assist in crafting adequate alternatives.”

The AmCham’s advice? Stall for time. “While there is still no reasonable alternative to this arrangement [...] it is absolutely vital that the Dutch government does not prematurely enforce the intended changes,” the AmCham writes. “Remember that haste makes waste!” Read: there must be something waiting in the wings before the duck-rabbit disappears – a new loophole that companies can use to avoid paying tax.

And what do you know. State secretary Wiebes gives the giant multinationals what they want. The European Commission wants to bury the duck-rabbit by 2019. Wiebes doesn’t. “The Netherlands is targeting an implementation date of January 1, 2024,” he writes to the House of Representatives in November 2016.

This time the House does protest. Representative Arnold Merkies submits a motion that calls on the government to hold firm and accept the European Commission’s proposal: January 1, 2019. A House majority passes the motion, but though his own party votes in favor, minister of finance Jeroen Dijsselbloem tables the motion. He urges the EU Economic and Financial Affairs Council to choose a later date. “Given the long-term impact these measures will have on our economy, we truly need more time," Dijsselbloem explains to his EU counterparts.

The House is not amused. A second motion is passed. This time Dijsselbloem surrenders. The EU’s ministers of finance reach a compromise: the duck-rabbit must die by 2020.

But the AmCham lobbies on

If you’re thinking the Netherlands will no longer be a tax haven after 2020, think again.

Even before the duck-rabbit’s demise is set in stone, the Ministry of Finance and the AmCham link arms in a feverish search for alternatives. “In informal talks between [the ministry] and AmCham, we have agreed that AmCham will suggest alternatives to the current mismatch arrangement [read: the duck-rabbit] to have in reserve,” ministry officials write as early as 2014. “AmCham will deliver these alternatives and discuss them with the ministry.”

This is followed a month later by a letter containing AmCham’s wishlist. “In this letter, we present a number of possible ‘avenues of solution’ for shoring up the Dutch fiscal business climate after BEPS [the OECD project to address tax avoidance],” writes Arjan van der Linde, chairman of the AmCham’s tax committee and tax director at General Electric. One of the points on that wishlist – expanding the dividend tax withholding exemption – will probably become law in 2018.

In November 2016, Dijsselbloem also argues in favor of lowering corporate tax to “remain competitive.” (A few months later – when elections roll around – he argues in favor of raising corporate tax.)

What to do with the stockpiled profits?

What can American companies do with all their untaxed savings? They can’t just bring the money that’s idling in Dutch duck-rabbits back into the US, or the IRS will come calling. For example, suppose Pfizer wants to pull $10 billion out of the Netherlands to pay its shareholders a dividend. First it will have to hand over $3.5 billion to the American tax authority.

But there are a couple of attractive options for American multinationals. The first is to buy foreign companies. As long as the money stays outside the US, you see, it stays untaxed. And indeed, recent years have seen an explosion in American acquisitions of European companies.

Activision Blizzard is a good example, as it happens. In November 2015, the game developer announced it was buying Ireland’s King Digital Entertainment, the maker of the popular mobile game Candy Crush Saga. More than half of the $5.9 billion Activision paid to acquire King came from its untaxed stash in the Netherlands. “A fantastic move,” gushed a stock analyst in Bloomberg Technology. “One of the highlights of the deal.” The purchase even received a Tax Deal of the Year award from the International Tax Review.

Even better is what’s called tax inversion. For example, last year Pfizer attempted to buy Ireland’s Allergan using $115 billion it had stored in the Netherlands. By setting up the acquisition right, Pfizer can change its corporate nationality from American to Irish. And that’s a real advantage, because in Ireland the corporate tax rate is just 12.5%.

At the last minute, however, Obama stopped the merger from happening, by enacting new rules that made this kind of tax inversion impossible.

Trump – surprise – wants to overhaul those rules

Which brings us to our third option: just bide your time. If history is any guide, the US government will eventually swing legislation back in your company’s favor.

In 2005, for example, Congress passed a law that allowed American multinationals to bring home their foreign profits at a temporarily low rate of 5.25% – a mere one-sixth of the regular tax rate. Some $362 billion flowed back into the US as a result. A quarter of that – a whopping $90 billion – had been cached in the Netherlands.

Trump, for all his MAGA rhetoric, reinforces American companies’ biggest lesson: earn your money in other countries and you’ll pay less tax

The promise was that the law would create American jobs. But it didn’t, revealed an analysis conducted by the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service. Nonetheless, another profit repatriation tax break will probably take effect soon. Trump’s proposed tax plan includes a temporarily reduced rate of 10% on overseas earnings that are returned to American soil.

And so Trump, for all his MAGA rhetoric, reinforces American companies’ biggest lesson: earn your money in other countries and you’ll pay less tax.

Hope for the future

During my investigation, one thing became very clear. Convoluted corporate structures that most people would find repugnant still enjoy broad support among tax specialists. “If we don’t do it, Bermuda will,” they say. And in Bermuda they no doubt say the same thing about the Netherlands.

“If we don’t do it, Bermuda will,” they say. And in Bermuda they no doubt say the same thing about the Netherlands

At some point in the confidential documents obtained under the Dutch Freedom of Information Act, an official moans about how difficult it is to communicate with the Dutch Association of Tax Advisers (DATA). “The government must draft tax policy with society as a whole in mind,” he tries to explain to the lobbyists. “In our talks, this seems to be a point the DATA is unable to comprehend.”

The good news is a public debate on tax avoidance is finally underway. And it’s here to stay. The proof? Just last month, the Dutch House of Representatives held a debate on tax rulings – tax rulings! Just a few short years ago, that would have been unthinkable.

Decisions that once took place in the shadows in the Netherlands have been thrust out into the open. Now it’s America’s turn to let sunlight do its work.

Neither Alexander Hent of Activision Blizzard nor the AmCham responded to our request for comment. The Ministry of Finance declined to comment on the issue, as did Joop Wijn. When asked, former Finance Minister Wouter Bos said he “couldn’t remember a thing” about the treaty.

—Translated from Dutch by Grayson Morris and Erica Moore

(All Dutch document titles and quotations have been translated by De Correspondent.)

More from De Correspondent:

This is how we can fight Donald Trump’s attack on democracy

The news provokes outrage every day, but it rarely inspires sustained resistance. Now that Donald Trump has launched a frontal assault on democracy, the press needs to fundamentally change tack. Journalists have to beat historians to the punch and write history – before it repeats itself.

This is how we can fight Donald Trump’s attack on democracy

The news provokes outrage every day, but it rarely inspires sustained resistance. Now that Donald Trump has launched a frontal assault on democracy, the press needs to fundamentally change tack. Journalists have to beat historians to the punch and write history – before it repeats itself.

Poverty isn’t a lack of character. It’s a lack of cash

I got to speak at the big TED conference in Vancouver about universal basic income and the poor. Here’s my TED Talk, where I lay out why “venture capital for the people” is such a good idea. For all of us.

Poverty isn’t a lack of character. It’s a lack of cash

I got to speak at the big TED conference in Vancouver about universal basic income and the poor. Here’s my TED Talk, where I lay out why “venture capital for the people” is such a good idea. For all of us.

The world’s not changing faster than ever at all

The world is changing faster than ever. And we’re going to have to adapt faster than ever too, just to keep up. At least that’s the cliché. But a new book gives short shrift to that notion. We’re not living in a period of technological revolution after all, author Robert J. Gordon argues, but in a period of technological stagnation.

The world’s not changing faster than ever at all

The world is changing faster than ever. And we’re going to have to adapt faster than ever too, just to keep up. At least that’s the cliché. But a new book gives short shrift to that notion. We’re not living in a period of technological revolution after all, author Robert J. Gordon argues, but in a period of technological stagnation.