“I feel goosebumps, my stomach churns and tears well [up in] my eyes whenever I cross Sydney Harbour in a ferry, kayak or look westward towards the city from the entrance to the harbour at Watsons Bay,” writes Jack Frisch, in response to the callout asking The Correspondent members to share their earliest memories.

“My earliest memory is one that I feel through my body rather than my mind’s eye,” he had begun, before adding: “I was two and a half years old when I arrived with my parents in Sydney in March 1951 on an immigrant ship from Europe. My parents and many others on the ship were Jewish concentration camp survivors who had had family members murdered by the Nazi regime and its collaborators. They were looking for a new life in Australia and most became successful Australian citizens. I think that the feelings I get are the result of the feelings of sadness, hope, uncertainty and trepidation passed on by the adults who would have been looking towards the distant cityscape as they entered the harbour.”

There have been many such evocative memories shared. The smell of fresh cactus reminded Xavier Moya of falling into a prickly pear, aged four. For Anne Brodie, it was watching a game of football from a pram. “My mother shouts: “Come on the Abbey, give us a goal!” I have no idea why we were watching football. My mother hates it to this day.”

Some of the examples are clear and detailed. Others lack colour; the location, or date, or sequence of events are hazy. But with each one, sharing a memory reads like sharing a piece of themselves. Reading so many from so early on in life has been both illuminating and perplexing.

It seems the most straightforward way to understand the first 1,000 days of human life – the time from conception to second birthday – is to ask what people remember. But how are early memories formed and why is there so much variation in the age of first recollection? Can we trust our early memories, given how fragmented they often are? And what is memory to begin with?

A couple of important distinctions are useful to start. The first is that memory is both the process through which we remember and the result of that process of recollection. The second is that when we talk about ‘memory’, we refer to one of two types: explicit or implicit memory.

Implicit or unintentional memory is what you draw on to perform most of your daily actions – from eating to walking or riding a bicycle. It is a skill you have learned that just seems to happen on autopilot.

Think of your memory as you would cloud technology

By contrast, when we remember elements of our childhood (autobiographical episodes), this is a form of explicit memory. There are two types of explicit memory: autobiographical and semantic. Semantic memory means remembering information such as capital cities or multiplication tables; knowledge you accumulate over your lifetime, but cannot point to a particular moment when you learnt the information. Language is a good example of this.

The process of memory-making is complex, but can generally be simplified into three steps: encoding, storage, and retrieval.

Think of your memory as you would cloud technology: when you upload a photograph to the cloud, you can star it, or tag it so it’s stored in a particular album. When you want to look at that picture again, the tag helps you find it, or maybe it resurfaces on your device when you’re looking at similar photographs.

In much the same way, smells or tastes are the most powerful prompt for memories to resurface – Proust’s madeleine, for example. And, as a starred image helps you access a picture quickly without having to search for it, the more you talk about certain memories the more readily available they become.

Despite their value in building understanding, no metaphor does memory justice. In reality, it’s much more complex.

For memories to form, neurons have to connect to each other via a synapse. And for those synapses to stick – meaning for those memories to be stored long-term – a process known as protein synthesis also needs to take place.

In early childhood, brain structures – particularly the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex which are responsible for memory – are still developing. The prefrontal cortex in particular only reaches its full development around the age of 25.

Memory is essentially the glue which holds our minds and our stories together

When a child is born and starts experiencing life, the neurons inside their brain start forming connections. Imagine it as thousands of explorers going out to get the lay of the land. They come across other neurons and establish connections, opening pathways. The connections keep growing until only the most used and prevalent pathways remain in use, and the other connections are shed. This process is called pruning.

Because of pruning, some events captured in our early years are likely to be hard to recall later in life.

The inability of children to store long-term memories before the age of three and a half is known as childhood amnesia. This can be explained in part by the ongoing development of neural structures within the brain, and also because toddlers can’t put these experiences into words. We can’t tag our photos in the cloud if we don’t have the vocabulary to do so.

Why don’t we remember?

For Sigmund Freud, the Austrian father of psychoanalysis, childhood amnesia was the result of repressing early memories. According to Freud, people decide to forget those first experiences because of guilt and shame. His theory on the inappropriate sexual nature of our first period of life is now highly controversial, but much of psychoanalytic theory is still based on the idea of dissecting early memories we have repressed.

Despite the controversy that surrounds some of Freud’s work, most psychologists agree with his idea that the lack of memories for early childhood doesn’t mean such memories didn’t make an impression. The general consensus is that early memories do matter, because they inform our later development and help us form our sense of self.

Culture is as important as biology in the formation of memories. Children have been observed to remember more if the primary caregiver passes on information through storytelling; if they grow up in cultures with strong oral traditions (be they Maori, Yoruba or Italian); and if they were raised in an extended family rather than a nuclear one.

In East Asian cultures, for example, there is less emphasis on the individual and more on the community compared to the West, according to psychology professor Qi Wang. This collective identity can explain why in a study comparing the earliest memories of Chinese and American college students, Chinese stories were briefer, more factual, and began around six months later.

Can we trust our own memories?

We’ve established that some memories from early childhood can be retained, although the average age we start to remember things, and the detail in which we remember them, depends, in part, on culture. So here’s a more difficult question: how do we know our childhood memories are real? After all, not even adult memories can be fully trusted.

In 1995 Elizabeth Loftus and Jacqueline Pickrell carried out an experiment in which they attempted to plant fake memories in the minds of 24 people, ranging in age from 18 to 53. The specific memory was of being lost in a shopping mall as a young child which, for all the participants in the study, had never actually happened. Yet, a quarter remembered the event, either in full or in part.

In another study, this time a survey that is both more recent (from 2018) and larger scale (6641 respondents), 40% of participants said they had a first memory that fell within the first two years of life, but gave details of emotions that the researchers considered “improbable” to have for such early recollections. The study concluded that memories of life before the mean age of 3.2 are unlikely to be real, and that anything that comes earlier is “fictional”.

As you might imagine, not everyone agrees, and the theory remains hotly contested. Not every academic has the same view on what exactly constitutes a memory: is an image enough, or does it need to have contextual information? As with so many questions that surround memory, the answer from the scientific community is: we’re just not sure.

As a process that remains partly shrouded in mystery, scientists will inevitably continue to delve into what memory is, how it is formed and how it can be manipulated. But the power and value of early memories aren’t just derived from their veracity. It scarcely matters if a memory is true or not, lived or imagined. Memory has personal and political power.

Think of the children of Argentina’s desaparecidos: infants, born in captivity, separated from their families and given out in adoption – sometimes only hours after being born – during the South American nation’s brutal crackdown against political dissidents. While few, if any, of the estimated 500 children abducted at this time will have memory of that time, personal recollection doesn’t matter. Collective memory, of the pain caused, of relationships and family identities erased, has become something to fight for. Reconstructing memory is a way to get justice and reconstruct life itself.

For all its other definitions, memory is essentially the glue which holds our minds and our stories together. Eric Kandel, the neuroscientist who shared the 2000 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for his work on memory, put it this way: “Without the unifying force of memory, we would be broken into as many fragments as there are moments in the day.”

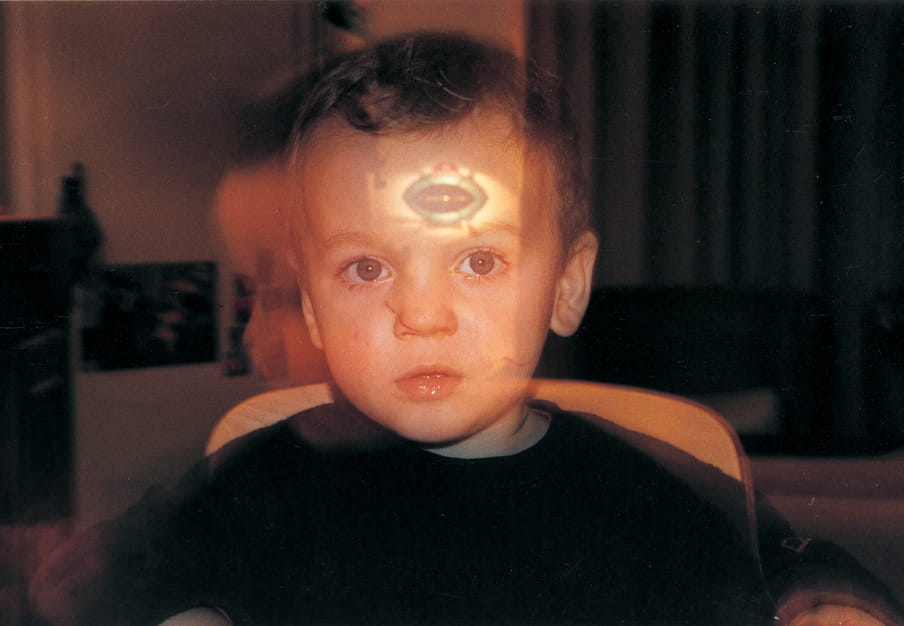

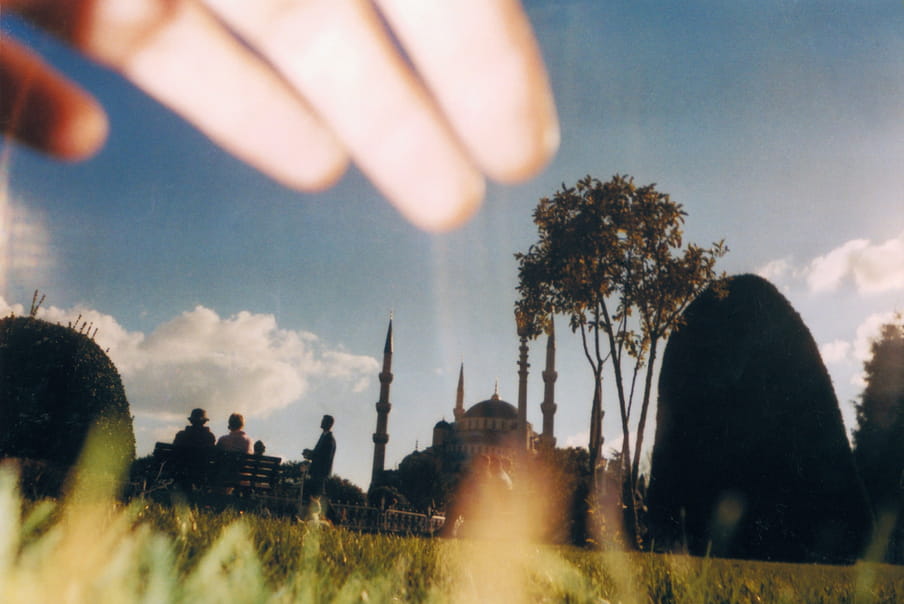

About the images

Placing callouts in several magazines, Sabine Verschueren, Erik Kessels, Hans Wolf, Andre Thijssen collected rejected photographs. Photos that didn’t quite turn out as the maker intended them to, but in some ways reflect memory better than a perfect picture: hazy and fragmented, not quite the same as the original experience. These unwanted surprises straight out of the analogue era - like jammed film or multiple photos all on one frame - are collected in the photo book ‘Wonder’: an ode to remarkable errors. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

Placing callouts in several magazines, Sabine Verschueren, Erik Kessels, Hans Wolf, Andre Thijssen collected rejected photographs. Photos that didn’t quite turn out as the maker intended them to, but in some ways reflect memory better than a perfect picture: hazy and fragmented, not quite the same as the original experience. These unwanted surprises straight out of the analogue era - like jammed film or multiple photos all on one frame - are collected in the photo book ‘Wonder’: an ode to remarkable errors. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Dig deeper

Eat, play, love: just how much are you shaped by your first 1,000 days of life?

Irene Caselli begins her investigation into early childhood with 1,000 questions on this critical period of development

Eat, play, love: just how much are you shaped by your first 1,000 days of life?

Irene Caselli begins her investigation into early childhood with 1,000 questions on this critical period of development