A race crisis. That’s what the world seemed to have descended into in the space of a few weeks.

A culmination of things getting worse and worse for people of colour and immigrant minorities on a global scale. Donald Trump. Brexit. Jair Bolsonaro. The constant agitation of far-right parties and media outlets against immigration. The rising incidents of hate crime against Muslims, Jews, African Americans and Latin Americans.

George Floyd’s killing by a white police officer in Minneapolis was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. It triggered a global protest movement that suggested that something had burst. And indeed, something did burst. Something had come to a head. Because things are getting worse.

But there’s another side to the phenomenon: it happened because things are also getting better.

Why it’s different this time

The killing of unarmed black men at the hands of white police officers is nothing new. Neither are race riots sparked by such assaults. There is a roll call of victims who are now household names. Trayvon Martin. Michael Brown. Rodney King.

A few factors related to the timing and nature of Floyd’s killing certainly make this time different. The particularly graphic nature of Floyd’s death is one. Suffocating in plain sight elicits a far more visceral response than a shooting or a death in custody. The lockdown is another, enabling the message of Black Lives Matter to resonate in the vacuum of a public life brought to a halt. But none of this can be considered elemental.

There are more structural, long-term forces that sparked the global protests against racism this time – and all of those forces point to one underlying pattern: racial progress.

Undeniably, there is a racism crisis. But it has been brought to the world’s attention because there are many more people of colour able to amplify the demands for racial justice

Over the past 50 years, significant strides have been made for people of colour in the United States and western Europe, both in terms of economic status and political capital. On top of that, the resulting empowerment has been boosted by the clout of a second generation of brown and black immigrants.

Undeniably, there is a racism crisis. But it has finally been brought to the world’s attention effectively because there are many more people of colour able to amplify the demands for racial justice. When made, these demands are met with more favourable reception and more solidarity than in the past, because white people’s attitudes towards racial equality are improving significantly as well.

The result: more protest and more solidarity with that protest.

With a certain kind of progress comes power

Communicating race grievance in a way that catches global attention requires more than just bodies on the streets. It requires an entire ecosystem of articulating those grievances and sharing them in ways that resonate.

To do so, people of colour have to be sufficiently enfranchised. They need to have the tools and confidence to protest and the ability to make their case in mainstream media. In short, they need to have access to white spaces, comforts and privileges that previously were shut off to them – higher education, higher income, white collar jobs.

Black Lives Matter as a movement is a response to things getting worse, but is itself a symptom of things getting better

And that is exactly what has happened over the past 50 years. The spaces, comforts and privileges previously only reserved for white people have now enabled a sufficient number of people of colour to organise campaigns, contribute disposable income, and advocate on behalf of other people of colour in public space, the media, politics, and the legal realm.

That is to say: Black Lives Matter as a movement is a response to things getting worse, but is itself a symptom of things getting better.

Enfranchisement through rising income and education

There are two patterns in particular that have led to the empowerment of black people to voice their concerns. The first is socio-economic: the rising household income of African Americans and their transition from blue collar to white collar jobs. The second is generational: the coming-of-age of a new – vocal – generation of black Americans and immigrants of colour.

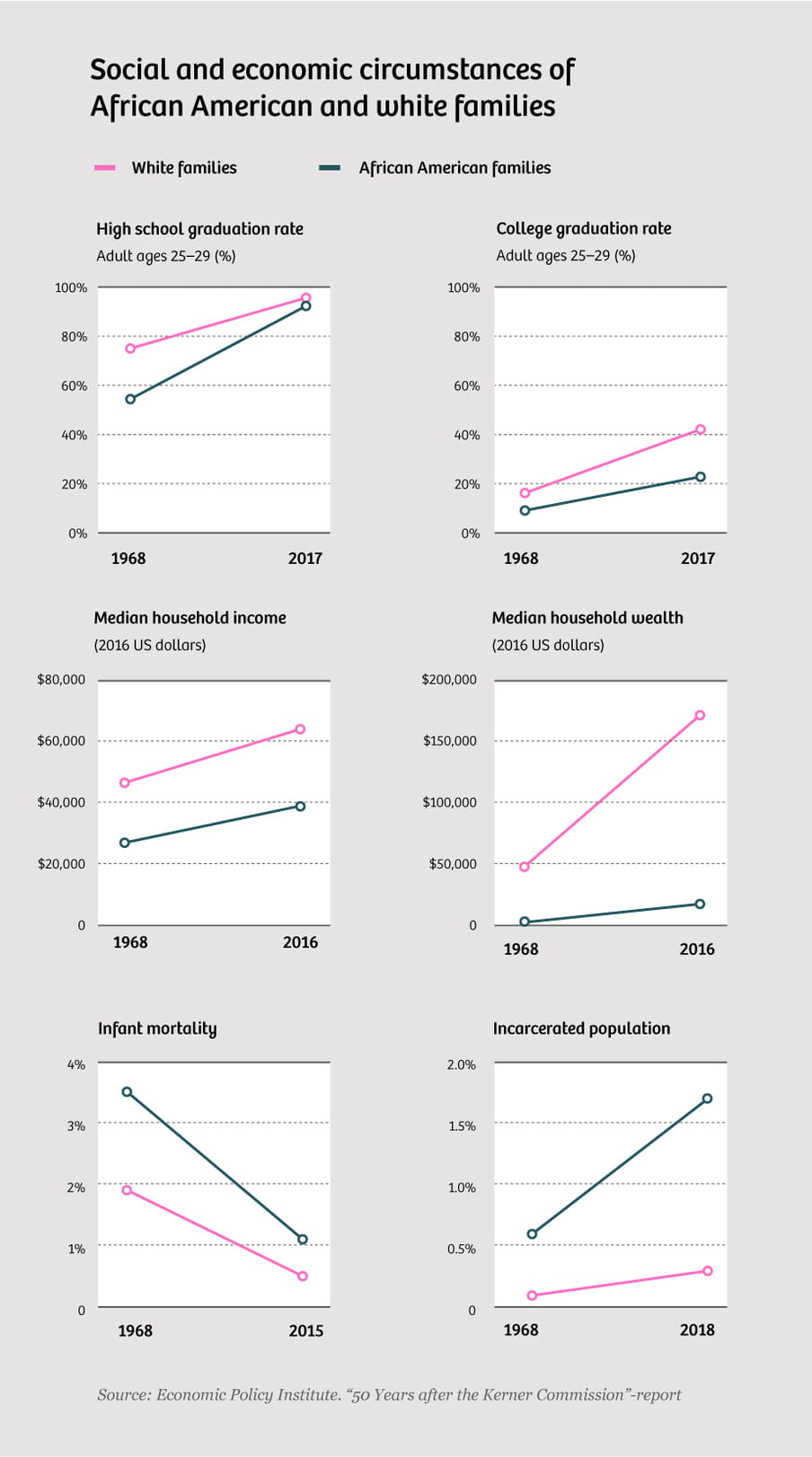

From the 1970s to 2016, the median African American in the United States climbed from the lowest quarter of the national income into the 35th percentile. While huge disparities between white and black median income still persist, that change was sufficient to diminish the gap in income between whites and black by almost a third. Over the same period, the rate of African Americans aged 25-29 graduating from high school almost doubled to more than 90%. When it comes to college education, the difference is even more dramatic, more than doubling from just 9% to 23%.

This rise in household income is attributable in part to a migration from blue collar to white collar jobs. African Americans are now, in fact, overrepresented in the ranks of federal government, and 60% of African American women are employed in white collar jobs.

The cumulative effect is an increased access to, and visibility in, sectors that project the message of racial inequality, particularly the media and the political sphere. Along with that comes the benefits of creating activism networks, raising funding, and signal boosting race-related causes that in the past would have depended on the efforts of a single charismatic leader, such as Martin Luther King.

In journalism, for example, the increased presence of black journalists in newsrooms means that stories of racial justice are more likely to be covered. While African Americans are still underrepresented in US national newsrooms, they are proportionally represented, and in some cases overrepresented, in local newsrooms, which are more impactful in terms of civic engagement.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Wesley Lowery recalls one of his first assignments at The Boston Globe, where he went to cover a stabbing at a black neighbourhood in Boston. A middle-aged black man asked him where he was from, then responded, “The Globe? The Globe doesn’t have black reporters. What are you doing over here? You lost? Y’all don’t write about this part of town.”

But he was and he did, as did several other black reporters and editors who began to enter the media world.

Higher education and a larger presence in the media world opened doors for activists to engage with the public outside of their immediate campaigning circles too. The three women credited with the formalising of the Black Lives Matter movement – Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, Patrisse Cullors – all earned college degrees and published a host of articles in high-profile media outlets, while frequently appearing on TV and radio to draw attention to police brutality against black Americans. Their demographic’s incorporation into the political class helped raise such concerns into legislative circles as well, where another material change had been taking place over the past 50 years.

The rise of the political class of colour

A little over 50 years ago, there was not a single black member of the US House of Representatives, and not a single governor. As of 2019, there were 52. That number is even more significant as a share of the total number of seats in the House.

When that milestone was reached, it was the first time in history that the number of black members of the House of Representatives was equal to the proportion of blacks in the country as a whole. Overall, the current Congress is the most diverse in history, with non-whites making up 22%. Half a century ago, they made up just 1% of the House and Senate.

The progress of black US Americans in the field of local politics has been even more substantive. In 1967, the first black mayor of a big city was elected. Fifty years later, out of the largest 100 cities in the United States, 39 had elected black mayors. In 2019, the country saw the highest number of first-time elections of African American men and women as mayors, with nine taking office across the country.

The election of this new cohort of politicians is, in many cases, a direct consequence of their race, as they are elected by other black US Americans to further their causes. Almost 40% of black adults believe that "working to get more black people elected to office would be a very effective tactic for groups striving to help blacks achieve equality".

That faith has not been misplaced. During the protests, the black American mayor of Washington painted "Black Lives Matter" in large yellow letters on a street near the White House.

The rise of a new, connected and vocal generation of black immigrants

And then there is another, often-overlooked factor in the enabling of protests and activism: a new demographic of people of colour. The black population in the United States is not a static one that traces its lineage only back to the enslaved. Since 1980, the black immigrant population in the United States has increased fivefold from 816,000 to 4.2 million, constituting almost 10% of the total black population.

Within that population are immigrant groups that were fast tracked into higher-income white collar jobs due to their educational background. Also known as the “African brain drain generation”, these Black immigrants from the African continent, particularly from countries like Nigeria, are even more likely to have a college degree or higher than all US Americans – white and black.

But it is this group’s children who are having the highest impact on how race demands are projected – both in terms of numbers and influence. In 2016, almost 10% of black US Americans were second generation – that is, born in the US, but with at least one foreign born parent.

As a whole, black immigrants and their children make up almost 20% of the total black population in the United States. These children, already more likely to be given an advantage due to their parents’ white collar jobs and education, became incorporated further into mainstream society, able to demand equality without the sense of precarity and need to keep their heads down.

This second generation is faring better than their parents across the board – in terms of tertiary education attainment (36% vs 29%), median household income ($58,000 vs $46,000), and home ownership (64% vs 51%). They are also almost half less likely to be in poverty.

Socially, they are less cut off as well, forging more intimate connections outside their racial group, and seeing themselves as insiders rather than outsiders waiting to be let in. These second-generation immigrants are even twice as likely to have a spouse of different race or ethnicity when compared to all immigrants and all US adults. About 15% "marry out".

They are also more likely to embark on less "safe", careers such as medicine, in favour of jobs that have a higher influence on culture and values. Jennifer Lee, professor of sociology at the University of California, wrote about the choice of second-generation immigrants that did not fit with their parents’ idea of success, and identified this divergence as in itself a marker of success.

A whole new generation of entertainers and comedians popularising racism-related causes hails from immigrant families

"That Asian Americans are increasingly departing from narrow definitions of success," she surmised, "choosing alternate routes, and making it on their own should give their immigrant parents confidence that broadening the definition of success doesn’t mean failure; it means uncharted new horizons."

One of these new horizons is popular culture. A whole new generation of entertainers and comedians popularising racism-related causes hails from immigrant families. Just in terms of sheer numbers, they have bolstered the ranks of the anti-racist comedy circuit. Comedians such as Hasan Minhaj, Aziz Ansari, Mindy Kaling, Russell Peters and Ramy Youssef have been joined by a new generation of young black US artists, such as Issa Rae and Tiffany Hadish, to popularise notions of race injustice that encompassed all people of colour.

This cohort is pivotal in the new movement. They do not have the immigration status headaches of their parents’ generation. The lack of professional or even geographical mobility that is so often a limitation imposed by immigration statuses for refugees and asylum seekers is not a factor.

Twice as less likely to be poor, much more likely to own a home, and certainly more likely to have a large social support network outside their immediate families and ethnic communities, these second-generation children can rock the boat – knowing that even if it capsizes, they will not drown.

The black millennial powerhouse

This newly attained freedom and autonomy shows. Millennial black Americans in particular are more confident, more forthright about their racial identity, and less quiescent when it comes to racial discrimination than their predecessors.

According to one 2019 survey, "black millennials are more likely than the black professionals who came before them to feel they have a responsibility to represent their race, and they are more likely to feel they should bring their authentic selves to the office."

Their digital connectivity and freedom to express themselves online has also created a virtual sphere where their race and all its associated cultures in music, dance, film, and literature is a source of pride. African American millennials are more keen to try new tech products, 25% more so than other millennials; and they spend more time on social media than white peers too.

These are the young, gifted, and black of Nina Simone, but instead they are young, connected, and black.

And they form not just a national but global force. While the social mobility of the original black population in the United States is limited to North America, the pattern of more highly educated black and Asian immigration since the 1970s is worldwide. In the EU, over half of second generation migrants are employed in not just white collar jobs but highly skilled white collar jobs such as law, management consultancy, corporate finance, fashion, and media – outstripping first generation immigrants by almost a quarter and their non-immigrant white counterparts by 10%.

More tellingly, though, is the picture over time. First generation immigrants’ employment in these jobs has remained pretty much the same over the past decade, while for their children, it has gone up. Second-generation people of colour all over the world are a professional and cultural force to be reckoned with.

And their presence at the heart of hitherto white establishments has had another significant and very important knock-on effect. The softening of attitudes towards race on the part of white people.

‘The Great Awokening’ and the rise of white solidarity

The din of social media arguments and the adversarial format of race debates on TV and radio contribute to an overwhelming sense of an escalating race crisis. But this noise also obscures the fact that, on the whole, one of the reasons that the current movements for race justice are gaining traction is that people of all races have become significantly more sympathetic to the cause.

This development has two gears: a slower one, where positions have mellowed over the past three decades, and a much faster one, where attitudes have dramatically changed almost overnight.

The slower development saw some white US Americans change their attitudes on race so much that they’ve ended up to the left of even the classic black voter – a phenomenon so tangible that it was given a name: "The Great Awokening". It became more noticeable in the middle of the past decade, where white liberal Americans began to poll differently on issues of race, with more beginning to believe in institutional racism and less in meritocracy.

In 1977, 63% of Democrats thought that individual grit and willpower determined a black American’s success, not their race. By 2016, that had dropped to 28%. According to General Social Survey, "white liberals are now less likely than African Americans to say that black people should be able to get ahead without any special help."

Some have attributed this shift in attitudes to liberal Democrat presidents such as Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, who were more strident about racial politics, but polling evidence suggests that there was also an acceleration in the middle of the last decade, where the mellowing of attitudes turned into more active support, mostly due to the Ferguson protests in 2014.

But the quicker and more dramatic shift is happening right before our eyes. US American voters’ support for Black Lives Matter increased over the two weeks since the protest started by almost the same vector as it did in the preceding two years. The dynamics that are leading to breaking point are not related to increased intolerance of black people, but increased intolerance of racism towards black people. Long-term trends intersected with event specific sympathies add kindling to the flame of the Black Lives Matter movement.

This support is indivisible from the integration of more people of colour into white schools, jobs, and popular culture, and into a media and political elite that people take their cues from. Elites such as Barack Obama, who said after Trayvon Martin’s killing: “If I had a son, he’d look like Trayvon.” In other words, people of colour are in a process of "de-othering" – turning into friends, colleagues, and partners of white people.

In that sense, Black Lives Matter is a case study in how movements for equality by a certain group can connect with others and create a coalition, without that diluting or scattering the original grievance. A core of energy that radiates outwards, and where every layer brings its support, and its own political aspirations.

How this progress is used against people of colour

Now, we must pause for a moment. Because although all of this progress is remarkable and a pivotal part of the success of the racial justice movements around the world, it is important to note why it often isn’t regarded as such. These positive trends are not regarded as contributing to the traction of racial protest movement because they have been co-opted by those who wish to trivialise race concerns.

They point towards this progress as if any progress is all progress. Anti-racists then have to argue – rightly – against the advances in race relations because they have still not resulted in the eradication of either individual, or systemic racism. Pointing to any improvement is therefore often seen as apologism for racism. The result is that the latest Black Lives Matter protests, and more generally any race-related gripes, are attributed to an intensifying crisis, rather than to the fact that there is simply more tension, because there are more people willing and able to challenge racism.

The statistics can also be confusing. There has been a sharp rise in white hate crime, and foiled hate crime plots, both in the United States and in Europe against black people, Muslims, and Jews.

The election of Donald Trump, the Brexit referendum and the vice grip that a right-wing conservative party has in the United Kingdom all show an increase in popularity of nativist and white nationalist forces. But these trends are as much a backlash against the encroachment of demographic patterns and declining status of white populations as they are signs of an intensifying hostility towards people of colour.

The populists wouldn’t be on the rise if there was not so much progress to rise up against.

Why racial progress is relative, not absolute progress

In other words, progress cuts both ways. It provokes populists afraid of change, but also provokes the beneficiaries of that progress into demanding more change. The advances of black US Americans and people of colour in the United States and Europe lead not to satisfaction with how much better things are, but to an even clearer view into how much better they still are for white people.

To put it differently: a counterintuitive outcome of being let into white spaces is seeing for the first time just how nice they are, how much wealthier they are, and then becoming less satisfied with the new, relatively improved position you have gained. When minorities are accused of not being grateful for progress, this is why: they are seething at the yawning gap that is much more firmly in sight now.

Choose your metric, and chances are it will be one that shows a gap so large between white and black people that they may as well be living in different countries

These are fundamental disparities so large that they drown out any triumphalism or smugness about how far black people and people of colour have come. Despite rising median household income of African Americans, they still own a staggering one-tenth of the wealth of their white counterparts. Despite higher education levels and more white collar employment, they still earn a little over 80 cents to every dollar a white US American earns. They are still twice as likely to be in poverty, have a shorter life expectancy, and more than double the infant mortality rate. And to make matters worse: these are the areas in which African American prospects have improved over the past 50 years. These disparities apply across the board. Choose your metric, and chances are it will be one that shows a gap so large between white and black people that they may as well be living in different countries.

In other areas, there has in fact been dramatic deterioration. The black incarcerated population over the past 50 years has almost tripled. A black US American is today more than six times more likely to be incarcerated than a white counterpart 50 years ago. Is it any wonder that appeals for gratefulness and quietism fall on deaf ears?

Relative progress is not absolute progress, and these glaring disparities, as well as in some cases the clear regression in life prospects for those born black in America, are what continue to underpin the anger that spilled out onto the streets of the country, and echoed around the world.

Anti-racist movements have been empowered, not weakened

In today’s world, there are more people of colour in public life, in politics, in the media, in the office, in racially mixed families. And with their entry, power is shifting. With that shift comes discomfort and resistance from those who now have to give up social, economic and political capital when they have always had an advantage. And with that shift also comes an increased awareness on the part of people of colour of the difference that still gapes between them, and their white peers.

Demographics alone are no guarantee of progress. The increasing number of people of colour in the population alone is not enough to guarantee that their safety and rights are enshrined. The quantum growth of minority populations alone is not enough to hand them the resources needed to advance their racial causes, only the redistribution of power among those minority populations is.

The Black Lives Matter protests are different this time round because there are, for the first time, enough people that have that power to say enough.

Dig deeper

Why US Americans always end up with a president who is less progressive than they are

The majority of people in the US are progressive on the big issues, but the media and political establishment close ranks to make sure they get a card-carrying centrist candidate like Joe Biden. If progressives want to win, they’ll have to reframe the debate.

Why US Americans always end up with a president who is less progressive than they are

The majority of people in the US are progressive on the big issues, but the media and political establishment close ranks to make sure they get a card-carrying centrist candidate like Joe Biden. If progressives want to win, they’ll have to reframe the debate.