The late comedian Bill Hicks has a bit on how US presidents are elected. He introduces his theory by saying that he’s not a conspiracy nut, but that he’s sure that “a very small elite” runs and owns the media and business interests in the country. Once elected, those interests invite the new president “into a smoke-filled room” and say: “Roll the film.” Then, Hicks says, “this little film screen comes down [ ... ] and they show you the Kennedy assassination from an angle you’ve never seen before”.

"Any questions?” they ask, as the screen goes up again.

How a presidential nominee is born

I caveat what is to come by saying that I, too, am not a conspiracy nut.

But there are indeed a variety of ways in which things conspire to promote politicians who are most likely to maintain the status quo, even when voters do not want that status quo to continue. The philosopher Joseph de Maistre famously observed that every nation gets the government it deserves, but it may be a more accurate observation these days that every nation merely gets the government it thinks it deserves.

Convincing people they are not as progressive as they think they are is one of the most important, yet lesser known ways of gently but effectively cycling out change candidates from the system. This is why, and how, after three years of Donald Trump, a president who has exposed the pressing need for a root-and-branch rethinking of US politics, the Democrats reached deep into their resistance coffers and ended up with …

Joe Biden.

A resurrection

Biden’s surprising surge, described as a walk out of "the tomb of loser candidates" to frontrunner in less than a week, may seem like a damning repudiation of progressive politics, but it is less a statement on his supporters’ politics and more a reflection of what they have been told their politics is.

There is evidence to suggest that many US Americans, not just the "liberal elite" or those who live on the country’s coasts, are far more progressive than even they themselves think they are.

That evidence combined with how nomination processes play out points in one direction: despite not being particularly capable or inspiring, politicians like Biden still rise to the top because those who vote for them have been successfully talked out of their own aspirations.

A gap between perception and politics

When it comes to our political choices, we like to think of ourselves as reliable, rational adjudicators. But in each voter sit two political animals: one who has a very clear and specific idea of what policies constitute a free and fair society, and another who is very susceptible to what, and which person, opinion-forming forces say is valid and reasonable.

Research conducted by the Atlantic in 2012 revealed that, for example, there is a wide gulf between US Americans’ perception of inequality in their country, how much equality they want, and how much they think they want. Overall, the vast majority imagined the US to be a far less unequal nation than it was.

On minimum wage, taxation, gun legislation and climate change, the majority of people in the US leaned left

But, on the specifics, the more crucial blindspot was evident when US Americans were presented with an unlabelled distribution of wealth patterns of two countries: the United States and Sweden. When asked which wealth distribution they preferred, they overwhelmingly chose Sweden – a country often invoked as the epitome of a suffocating nanny state. A staggering 90% of Republicans surveyed actually seemed to like this socialist dictatorship in the north of Europe.

Polling summarised in 2017 by Prospect also reflected this disparity. On minimum wage, taxation, gun legislation and climate change, the majority of respondents leaned left. The summary concluded that "few Americans call themselves ‘progressive’, or think they share similar views with citizens of social democracies like Canada, Denmark, and Germany. But on most major issues, Americans lean left."

This disparity between the issues advocate and the themes observer who both sit within the US voter isn’t a natural one. It is manufactured. There is a playbook which, slowly, randomly, apparently inchoately but always inevitably, nudges the issues voter’s voice out, and a ballot is cast for a non-progressive candidate.

Mainstream stigmatisation and a pattern of near progressive wins

A "surprising" surge candidate who was "ascetic" is how the New York Times described this potential Democratic party nominee. This candidate was, among other things, "brilliant, self-absorbed, friendless, idealistic, erratic". Not only that, but he was also "doubted", the line of commentary went on, even by admirers, who could not imagine this candidate "as President, administering a vast government apparatus". The ambitious would-be nominee had launched the promise to "take back America from the confederacy of corruption, careerism, and campaign consulting in Washington”.

Was this about Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren? No, it was about Jerry Brown – Bill Clinton’s competitor in the Democratic party nomination race in 1992.

Despite his alleged erraticness and imagined inability to run a government, Brown, who ran on a grassroots campaign that proudly did not receive large donations from corporate interests or lobbies, emerged as the second place contender, beating far more mainstream candidates, securing upset victories in seven states. He landed several blows on Clinton, sending the latter’s campaign into disarray when he won Connecticut.

In our rear view mirror, Bill Clinton might seem like a sax-playing progressive, but at the time, he limped into the nomination with a real anti-establishment contender snapping at his heels. Brown not only resonated with his policies, he foreshadowed what would be the undoing of both Bill and Hillary – their sense that they are above the law.

But Brown was a "renegade" – and his framing as someone who was simply not fit for government finally caught up with him. Clinton prevailed, and the rest is history.

A systemic feature, not a bug

Brown is not an anomaly. There is a systemic dynamic that works against candidates like him, that is, those with a change agenda that challenges both the Democratic party structure and the established socio-economic arrangements of the country. They are stigmatised out of the process, even when the policies they promise to deliver are popular with voters.

There are two ways this slow but fatal marginalisation happens: one is through the media, and the second is through the political establishment. And here’s the interesting part: not by right-wing or conservative voices, politicians and media outlets, but by other Democratic party members, liberal platforms, and the intellectual ideas complex, which comprises academia and prestigious newspapers and magazines.

The collective efforts of these two institutions, often unconsciously and in an uncoordinated fashion, frame a candidate and their policies out of viability. The marginalisation follows a pattern. It tracks Mahatma Gandhi’s famous saying, but with a less happy ending: first they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then ... you lose.

A media and Democratic party working in tandem

Take Bernie Sanders.

First, the media just ignored him, leading to what came to be called a "Bernie Blackout". One study even referred to it as the “invisible primary” of 2015, where all Republican candidates individually received more coverage than Sanders. Hillary Clinton received three times more. Then, they laughed at him. "Long shot" Sanders with the funny accent and unruly hair. Then they fought him. "How Socialist IS Bernie Sanders?" asked the New Yorker. "Just how radical is Bernie Sanders on foreign policy?" mused the Washington Post. To New York Magazine, Sanders clinching the nomination would be "an act of insanity".

Then he lost.

First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then ... you lose

It is a pattern that is followed not just in presidential primaries. Pundits and analysts ignored the potential of local level candidates such as representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley and Rashida Tlaib (collectively known as "The Squad"). When they succeeded in becoming elected, they presented them as part of a "radicals versus moderates" battle, constantly depleting their political capital. The word "radical", one that sits alongside the word "extremist", places them outside the viability spectrum.

Alongside the media, there is the Democratic party machine. A political behemoth that works on another front to paint progressive candidates as not only too radical, but unfit, angry, and naive all at the same time. Speaker of the house Nancy Pelosi dismissed the members of The Squad as simply “four people” who “didn’t have any following”. They have "their public whatever," she said, "and their Twitter world”.

This friendly fire has significant power. In 2020, Warren went from leading the field to dropping significantly after being savaged by other nominees for her Medicare For All plan, which was accused by Biden and Pete Buttigieg of being radical, expensive, and naive (like Sweden’s, dare I say). After such dismissal, a strategic coordinated effort starts to bite. Political points are collected, pooled, and then handed over for free to what the party has decided is the continuity candidate.

This sort of consolidation around Joe Biden as the centrist candidate transformed the landscape as he was awarded the political capital of other nominees. Candidates such as Amy Klobuchar and Buttigieg dropped out and lent him their endorsements. Despite being an initially remote possibility with few policies that excited or inspired voters, Biden clinched the nomination because of a perception that other candidates were wild cards, and a Trump trauma that demanded a return to "normal". His trajectory was not organic, but manufactured. A synthetic victory.

An avoidable trap

But the conclusion to be drawn isn’t that US Americans have no appetite for more progressive politics, or that they would rather have Trump over a candidate that would make their lives better (although obviously for some this is true). History, polling patterns and a clear disconnect between what voters want and what they vote for show that the appetite is there, but that its satisfiers and their policies are stigmatised.

The way out of this marginalisation is to approach it head on by challenging media frames, be more calculated about presentation, and be more aware of the buzz concepts that are easy to trivialise.

Righteous anger is what progressive candidates try to harness. But sometimes this brings with it an urgent, some would say haranguing, tone of frustration. Progressive arguments are well trodden, but expressing them in worked up moral evangelism makes it easy to discredit them as emotive and immature. Anger, on the whole, is a bad look and an open goal.

Populist rage tends to work for right-wing candidates, but not for the left. It becomes too easy to smear angry candidates, and in fact bully them, as disruptive politicians who have only ideas but no understanding of how the real world works.

The view of Obama’s presidency is jaundiced in hindsight as a failed incrementalist centrist exercise, but he was the most successful Democratic candidate of recent times in winning people over to what was ostensibly a change agenda by nailing this sweet spot of expressing disaffection. Granted, he had exceptional messianic charisma and a racial background that made it hard for other Democrats to attack him without looking racist. But most crucial to his success was his way of framing aspirations positively without coming across as vindictive, angry, or easily dismissible as an ideologue.

Instead of railing against corporate media bias, a more fruitful route is to disarmingly challenge their framing. In a 60 Minutes interview, when Anderson Cooper called Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s tax position "radical", she responded by saying: "Well, I think that it only has ever been radicals that have changed this country." He pressed her, thinking perhaps he had nailed her on this. "Do you call yourself a radical he asked?" Her reply turned the tables. "Yeah. You know, if that’s what radical means, call me a radical."

The moral framing of a nation of people living in poverty who cannot access healthcare is powerful, but could also benefit from a more pragmatic spin – of healthcare as an investment in the future of the country, one that drives productivity, stimulates growth, and protects the economy from public health disasters. The same goes for the allegation of "big spending" and the demonisation of big government.

When asked in a debate with Hillary Clinton how he would allay US Americans’ fear of big government, Sanders replied with a series of facts about unemployment, crumbling infrastructure, and loopholes that enabled multinational corporations to stash money away in tax havens. Sanders could have recast the concept by illustrating how big government improves lives every day, and the credit is given instead to private enterprise.

He could have said: “You know that iPhone you love? The innovation that was brought to you by this wonderful private company, run by a genius entrepreneur called Steve Jobs, a man who honed his craft in the hotbed of innovation that is Silicon Valley. This phone, that innovation, the entrepreneur’s career, all were made possible almost entirely because of the US government. 95% of the technologies in an iPhone were invented at government-funded universities and in the army. All the digital infrastructure that made Silicon Valley rich was funded by the government. All the patent laws that made Steve Jobs a billionaire are government enforced. And yet government is the dirty word here?"

The options presented to people in the US increasingly no longer reflect their political needs

In other words: he could have turned the tables if he reframed "big government" as the pillar behind what US Americans not only love but think of as antithetical to government: successful businesses, entrepreneurship, innovation and empowerment to make money. If it wasn’t for "big government", none of that would even exist. Sanders instead stuck to completely valid, but ultimately paradigm reifying notions of inequality.

They may seem like small adjustments, but they are the first steps towards fortifying progressive candidates against the mobilisation of the media and the Democratic party to corner them on the stereotypes.

It’s not quite the smoke-filled room of manipulative corporate powers, but it is widespread, diffuse and embedded enough to have broadly the same effect. It doesn’t take a conspiracy theory to see that this system consistently reproduces the same politicians, no matter how much the world, and their voters, have changed.

The options presented to people in the US increasingly no longer reflect their political needs. During the last election, both candidates, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, had the lowest approval rating ever recorded for a presidential nominee in their respective parties.

The grinding away of candidates that deliver to US Americans what they say they want is nothing short of the erosion of the very essence of the democratic process. Instead of a screen showing the Kennedy assassination from a different angle, candidates are shown a reel of scoffing, sneering, attacking, and rank-closing on the part of the media, and their own party members. Assassination by a thousand cuts.

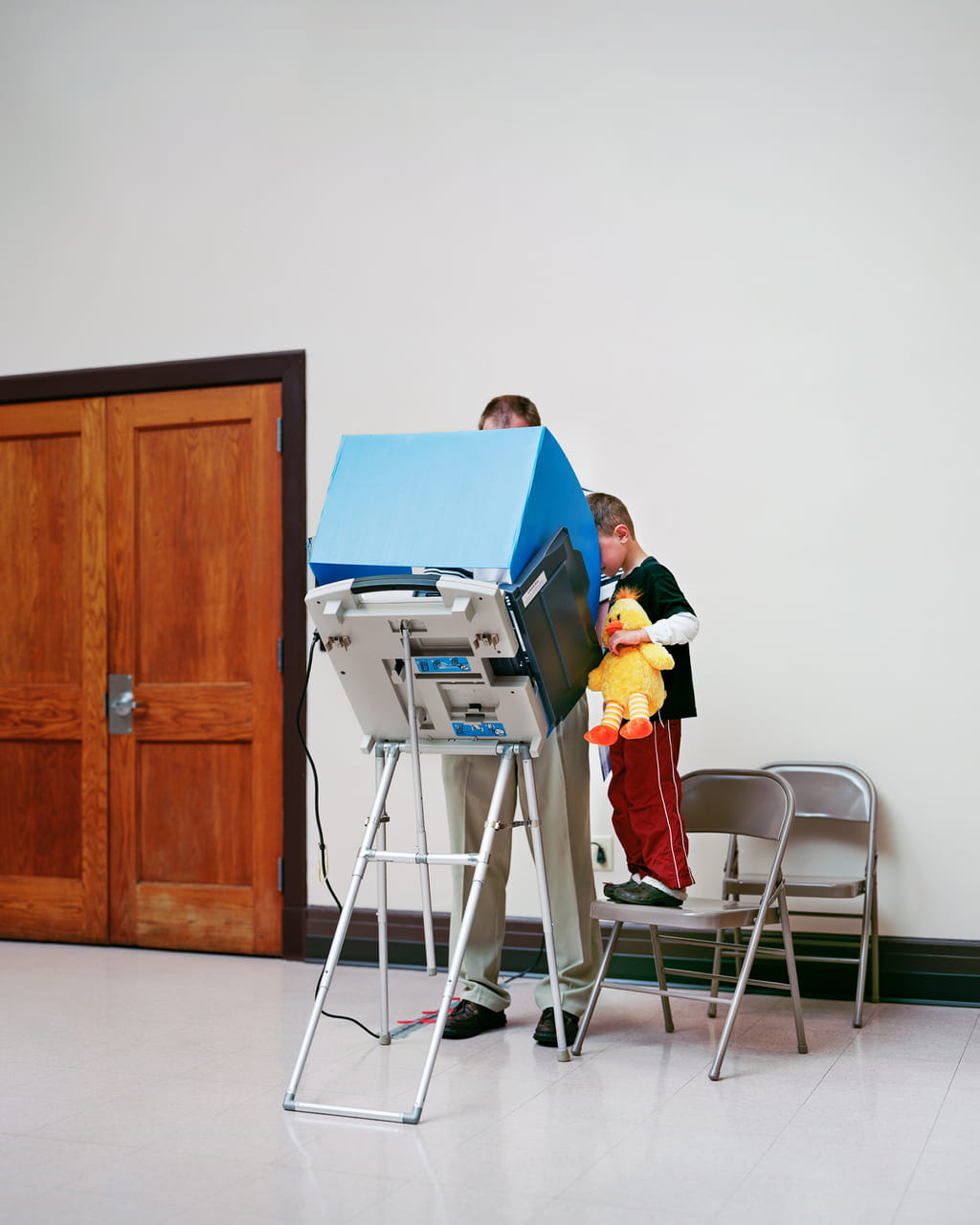

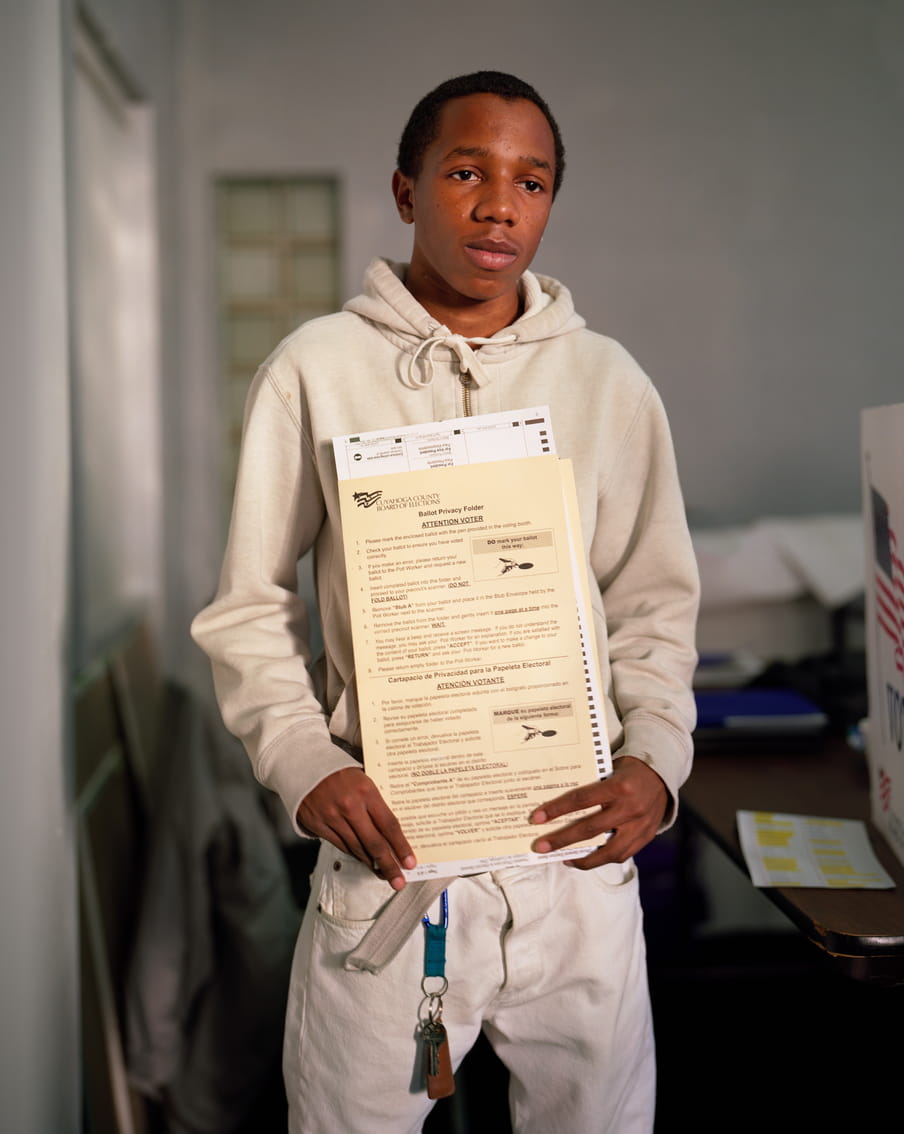

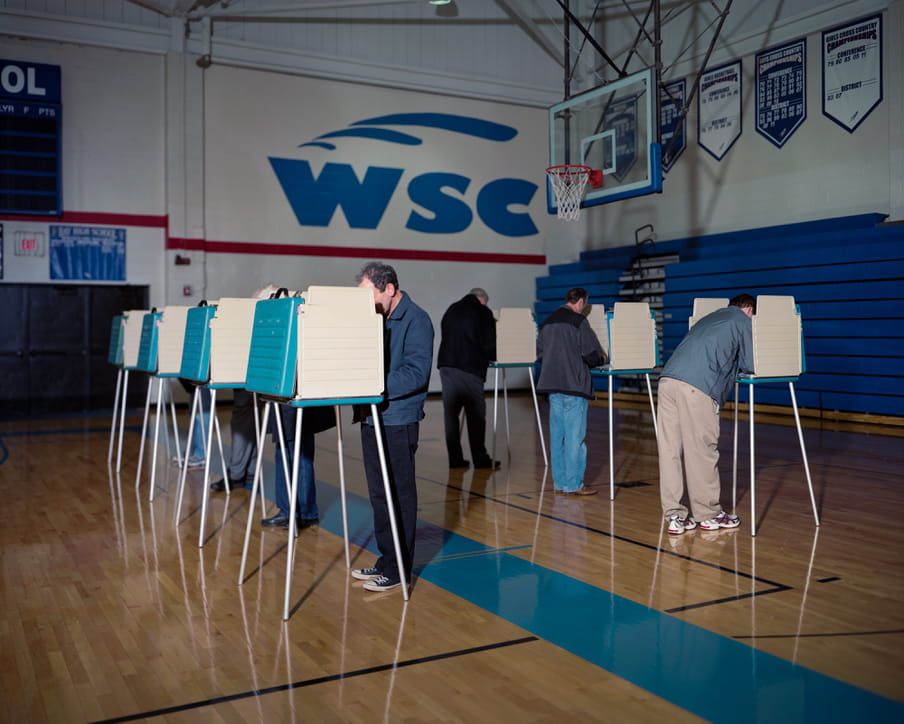

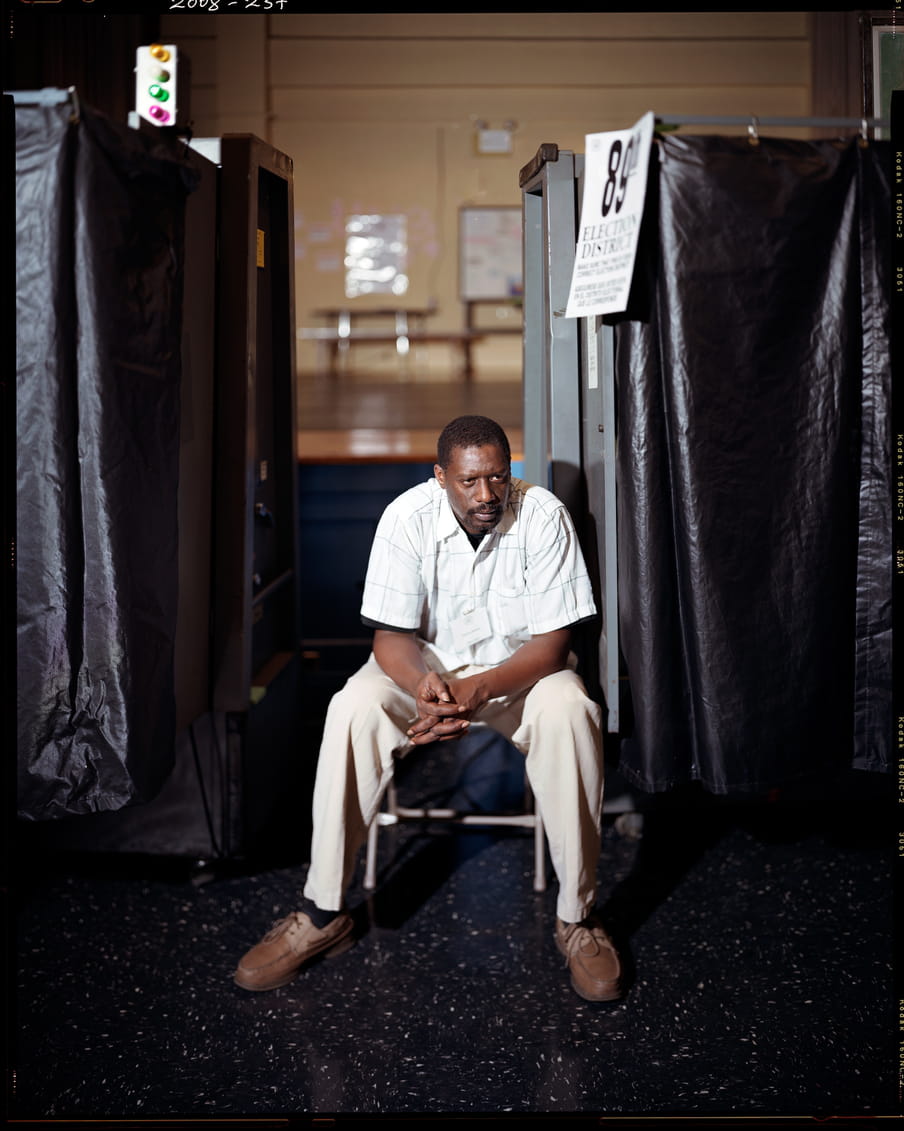

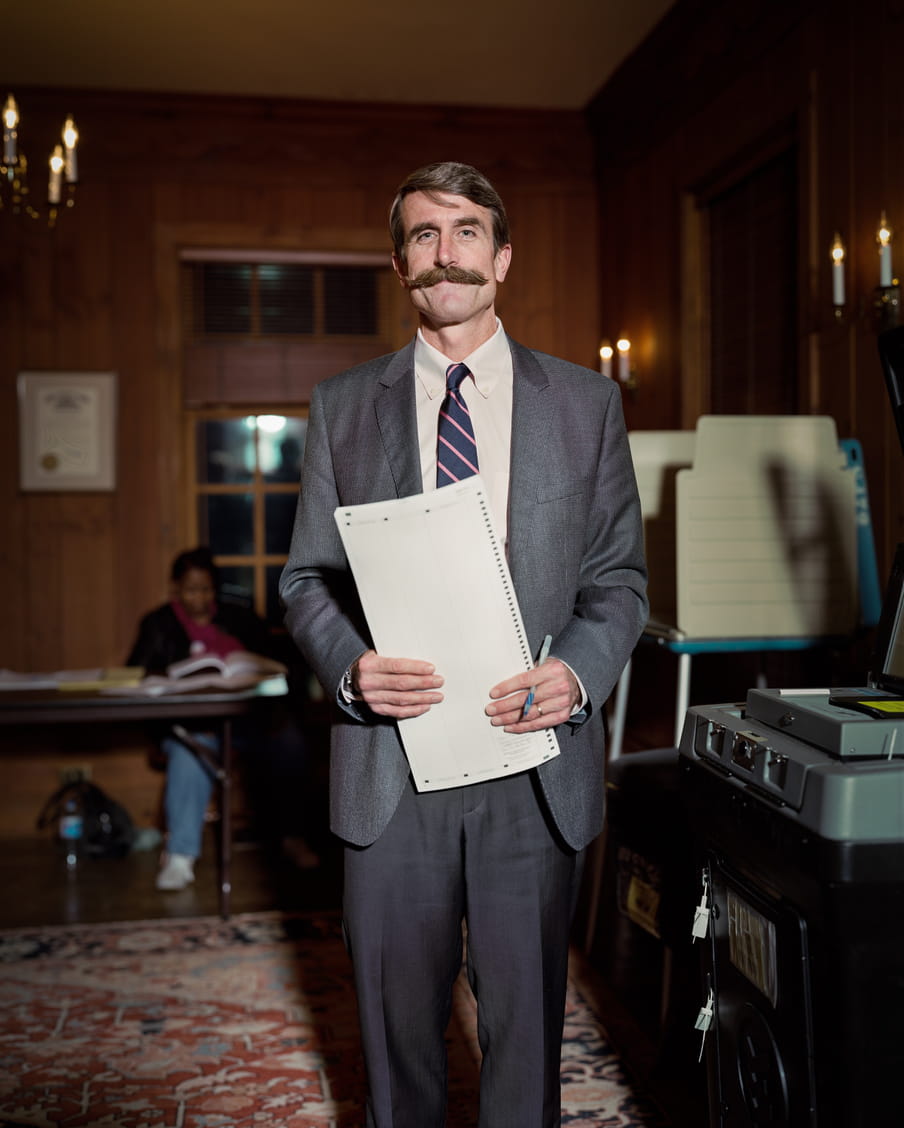

About the images

Greg Miller has been photographing polling places and voters since 2004 (the year Bush defeated Kerry). What fascinates him is that from the voter’s perspective, regardless of what they think about their candidate’s options or whether they believe any great change will take place, they have either retained or overthrown government by casting one vote. He thinks of his pictures as windows into what that process looks like up close. (Isabelle van Hemert, Image Editor)

About the images

Greg Miller has been photographing polling places and voters since 2004 (the year Bush defeated Kerry). What fascinates him is that from the voter’s perspective, regardless of what they think about their candidate’s options or whether they believe any great change will take place, they have either retained or overthrown government by casting one vote. He thinks of his pictures as windows into what that process looks like up close. (Isabelle van Hemert, Image Editor)

Dig deeper

Democrat or Republican, on the big polarising issues, you actually agree

The evidence is clear: once US Americans drop their labels, they are more aligned on what they actually believe their government should do – yes, even on healthcare.

Democrat or Republican, on the big polarising issues, you actually agree

The evidence is clear: once US Americans drop their labels, they are more aligned on what they actually believe their government should do – yes, even on healthcare.

The real reason we’re ad free (and six other questions from our members, answered)

What do we mean by constructive journalism? Why do we have members and not subscribers? And you get it, we’re ad free. But so what? Managing editor Eliza Anyangwe and founding editor Rob Wijnberg answer the seven most frequent questions we get about The Correspondent.

The real reason we’re ad free (and six other questions from our members, answered)

What do we mean by constructive journalism? Why do we have members and not subscribers? And you get it, we’re ad free. But so what? Managing editor Eliza Anyangwe and founding editor Rob Wijnberg answer the seven most frequent questions we get about The Correspondent.