This is an excerpt from my book The Future Earth: A Radical Vision for What’s Possible in the Age of Warming.

Radical change is now inevitable. It’s up to us to foster new conversations that confront this truth head-on yet are imbued with the kind of patience and care necessary to finally turn our intentions into meaningful action. We must begin a transition to a new kind of environmentalism that reflects the way the actual environment works. Not a demonstration of individualism or moral superiority, but an actionable, scalable model for a new way of life rooted in collective support and universal justice.

Throughout the next decade, we will experience both creative imagination and creative destruction, which is likely to produce a deep and abiding sense of civilisational anxiety. Certain times and certain spaces make us feel uneasy by their very nature: dark, empty stairwells; rest stops along the highway; the aftermath of a breakup. These are liminal spaces. If you find yourself spending more than several minutes in a liminal, or transitional, space, your inner lizard brain wants to flee – alarm bells begin to ring, something isn’t right. Because they transcend our normal understanding of how the world is supposed to work, they feel haunted. Liminal spaces are temporary, incomplete, and portentous. They imply possibility to such a degree that it is sometimes literally frightening.

Right now, Earth – the entire planet – is a liminal space. We are starting to learn this fact, that radical change is inevitable, yet we don’t know exactly what it’s going to look like. But this time is also vitally necessary in order for us, as a species, to figure out what we’re about to become.

Samantha Earle is a philosopher at the University of East Anglia, who specialises in liminal spaces. She firmly believes that western civilisation is currently ripe for radical change. Talking with her was the most transformative conversation I had while putting together this book. Philosophers like to speak of an “imaginary”, or a guiding, framework for organising society. Earle isn’t under any illusions that this process is going to be easy. But just as climate scientists are certain that our current path will lead to inevitable destruction of our planet’s fundamental life-support systems, Earle is certain that our prevailing guiding frameworks for civilisation cannot last.

“We’re at that time where the problems of the world just can’t be answered by the prevailing imaginary,” she told me. “We are in a time of breakdown.”

Radical change

That this breakdown in our society is happening precisely during a breakdown of our atmosphere and ecosystems is no coincidence. Through our daily thoughts and actions, we constantly reproduce our society. Most of that happens unconsciously or by routine or habit, or because exposing ourselves to new thoughts and actions involves risks we’re currently unwilling to take. But everything we do every single day is a choice, which means different choices are possible.

“The major problem with society is that we don’t even recognise that we have a particular imaginary, that this is not how things have to be,” Earle told me. During normal times, “we lack critical awareness, and we lack the capacity to radically imagine”.

This is why opponents of radical change have successfully categorised efforts to protect the environment or reverse the effects of climate change as personal sacrifices. We focus on the inconvenient downsides of taking the train over a car-share service, for instance, instead of imagining or working toward a world where driving in cars simply doesn’t exist because cities are designed with people in mind. We choose to keep funding fossil fuel companies because they’ve spent billions of dollars making sure our lives appear easier when we buy their products. The status quo is comfortable for a reason: it makes daily life easier to manage, especially when the alternative doesn’t yet exist – or, more accurately, when those in power are actively opposed to making a better world a reality.

In the midst of a liminal space, however, anything is possible. “Liminal space is a time of radical uncertainty where the foundational concepts of the way in which we’ve been living, and around which society is organised, no longer make sense,” Earle told me. “It’s not just that we’re unable to make sense of the problems that we’re facing. We can’t even conceptualise them. It’s a time almost of being suspended – it has profound existential implications. You still have an imaginary, only it doesn’t work, and you don’t have another one in place yet, and everything is up for grabs.”

The first step in moving through this space is to acknowledge the discomfort we are in right now as individuals and as a society. There’s creative power in that discomfort – it helps us to see the possible paths before us with clear eyes. It helps us to imagine something better.

Radical change isn’t something that most of us choose to think about very often in our free time. It’s unpleasant to consider how quickly our planet is shifting into a new and more dangerous version of itself. We don’t want to contemplate the delicate balance between environmental calamity and our drive to make our lives better, but we don’t have that choice anymore.

How do we build a new path?

So where do we go from here? How do you and I use this existential dread as a motivating force to imagine a different path? And then how do we build that new path?

“Climate change is first and foremost a problem of our relationship with the future,” author and philosopher Alex Steffen told me in the early stages of writing this book. “The way that we think about the future is almost entirely cultural. If we can’t adapt our cultural perspectives to include the idea that we need to be in a sustainable relationship with long-term systems, none of the other actions we need to take are going to happen.”

A recent study mapped out a blueprint for how to enact the kind of change Steffen is talking about. “It’s way more than adding solar or wind,” said Johan Rockström, the study’s lead author. “It’s rapid decarbonisation, plus a revolution in food production, plus a sustainability revolution, plus a massive engineering scale-up [for carbon removal].” According to Rockström and his team, to get the math right, we need to cut global emissions in half by 2030, then cut 2030 levels in half by 2040, then cut 2040 levels in half by 2050. Even these heroic efforts will secure only a roughly 50-50 chance at achieving the 1.5-degree limit in temperature rise the world agreed to in Paris. By the time all that is done, my boys will be only a few years older than I am today. Zeke won’t even be able to vote until 2034. By then, if we do nothing, we’ll have lost our only remaining chance at a liveable world.

How this will actually play out is, of course, unknowable. But we can make some educated guesses. Meteorologists like me are used to predicting the future in a way most other professionals don’t. We can see the range of possible future weather events and envision what they will be like. To date, we haven’t done a good job imagining how the weather years from now will affect society. But for the first time, the Rockström study provides a simple way to think about it: transformational change, decade by decade, for the next thirty years.

A way out of the liminal space

Very few people are already living in this future world. Even fewer understand that our current actions require systemic change. And none of them are as famous, or as influential, as Greta Thunberg. The improbable fact that Greta, a 17-year-old Swedish girl, is one of the most powerful people on the planet is further evidence that the old rules no longer apply. Her ability to speak disarming truths about our climate emergency goes far beyond her commitment to a zero-carbon lifestyle. Her power rests in the fact that, when it comes down to it, she knows that these actions are only meaningful if they create radical and systemic change. The fact that her actions are so simple means that everyone can join her. She has shown us a way out of this liminal space.

A recent survey revealed that one in five people in the western world say they are now flying less because of the movement Greta helped start. In Sweden, there’s even a new word – flygskam, “flight shame” – and the airline industry there, built on the promise of eternal economic growth, is starting to get scared. SAS, the Swedish national airline, has called it the “Greta effect”. Representatives from all 29 companies on Sweden’s benchmark stock index now say that air travel in the country is likely to have peaked, permanently, because people are starting to understand that, in a climate emergency, there is no feasible alternative for jet fuel in the near term. And batteries weigh too much for jet-based air travel as we know it – that’s just simple physics.

The first glimpse I got of Greta was late at night, a silhouette wearing a blue jacket, standing in my living room, reading a handwritten note my toddlers and I had made for her. She and her father, Svante, had arrived at my home in Minnesota from Iowa City for a few hours of rest, in a Tesla loaned to them by Arnold Schwarzenegger. Over the past few months, she had addressed the European Parliament in Brussels, boarded a boat in the United Kingdom and sailed across the Atlantic, given a speech to world leaders at the United Nations General Assembly in New York, presided over the largest climate rally in world history in Montreal, and met a famous vegan icon pig in Ontario. The next afternoon she would depart for Pine Ridge and Standing Rock in South Dakota to meet the people who inspired her to take this trip in the first place. She was, in a word, tired.

During our time together, we were able to have breakfast and go for a walk – normal activities for two adults, two toddlers, and a teenager. A soft early autumn rain fell on us. Roscoe fussed that we were rolling him around in our red wagon instead of letting him ride his bike. Other than that, the day was like any other. Greta and her dad felt just like friends visiting for the weekend.

On our walk, Greta paraphrased the points from her recent speeches: we are still in the denial phase, she told me, still trying to convince ourselves that, among other things, we are doing enough, or that the problem isn’t as bad as it is, or that we don’t need to act like it’s an emergency. I’ve heard people make the same point Greta was making, but hearing these words directly from her, in my own neighbourhood, with my youngest child in a wagon and my oldest child in my arms, at a moment when everything I love felt so delicate and impermanent that it all could go away in an instant, hit me square in the chest.

A worldwide revolution

Just weeks after starting her school strike outside the Swedish Parliament in Stockholm in August 2018, then-15-year-old Greta Thunberg addressed world leaders at the UN climate summit in Poland. She spoke with the moral clarity of an entire generation sentenced to a desperate future:

Our civilisation is being sacrificed for the opportunity of a very small number of people to continue making enormous amounts of money.

Our biosphere is being sacrificed so that rich people in countries like mine can live in luxury. It is the sufferings of the many which pay for the luxuries of the few.

The year 2078, I will celebrate my seventy-fifth birthday. If I have children maybe they will spend that day with me. Maybe they will ask me about you. Maybe they will ask why you didn’t do anything while there still was time to act.

You say you love your children above all else, and yet you are stealing their future in front of their very eyes.

Until you start focusing on what needs to be done rather than what is politically possible, there is no hope. We cannot solve a crisis without treating it as a crisis.

We need to keep the fossil fuels in the ground, and we need to focus on equity. And if solutions within the system are so impossible to find, maybe we should change the system itself.

We have not come here to beg world leaders to care. You have ignored us in the past, and you will ignore us again. We have run out of excuses, and we are running out of time. We have come here to let you know that change is coming, whether you like it or not. The real power belongs to the people.

With these words, Greta Thunberg kicked off a worldwide revolution.

Our future is not up for debate

Since this speech, tens of millions of people of all ages in 183 countries around the world have joined her climate strike, buoyed by her clear vision of a world that’s not just survivable but thriving. People want something to hope for. People want to be asked to do something big. People want a chance to be courageous, a chance at shaping their own future. That is what this moment provides.

Of course, this remarkable moment in history didn’t just happen spontaneously. For centuries, millions of people, led mostly by women of colour, have laid this groundwork. “I am not saying anything new,” Thunberg wrote in a Facebook post a few months into her strike, which was inspired by youth protests in the United States on climate change and gun violence. “I am just saying what scientists have repeatedly said for decades.”

On the sidelines of the official United Nations climate negotiations each year, the voices of children in the global south, where forests continue to be devastated and extreme weather threatens normal existence, have long been drowned out. Greta’s message is breaking through and resonating today, I believe, because the environmental emergency that rich countries have inflicted on poorer countries for centuries has finally come home to roost.

We know that younger generations should be able to feel confident they’re inheriting a world that’s survivable. As that future has been put up for grabs, Greta has been able to amplify the kind of language that has been in use for decades among those in the environmental justice community where the act of producing and using fossil fuels has annihilated places, either through mountaintop coal mining, cancer alleys, or toxic groundwater, places like the forests and rivers of Appalachia and Amazonia, the coal export terminals of Australia, and the neighbourhoods of Flint, Michigan. The message from Greta is as clear now as it has always been: our future is not up for debate. We all deserve to survive and to thrive.

Greta’s rise to the de facto leader of a global youth movement is evidence that things are different now. We’ve known about climate change for a long time, and we’ve known the solutions for a long time: phase out fossil fuels, transform agriculture, restructure the way we live, and move. The solutions are the same as they always were. But something important about this moment is different: we’re finally ready to listen.

Greta’s revolutionary humanity is dangerous to the status quo

During our walk in the rain, I asked Greta what she thought the system would look like once we change everything.

“I don’t know,” she said, “it hasn’t been invented yet.”

It takes courage to try to change the world. It takes even more courage to admit we don’t yet know how we can change it. The kind of attitude Greta exudes in her public work and, in private, with me and my family – the courage of both knowing and not knowing simultaneously – is the foundation of the work ahead of us and a prescription for how to accomplish it: an openness to a world beyond our ability to anticipate.

Greta is a regular person; she doesn’t act like a celebrity. What makes her special is that she has read and understood climate science and is living her life as if the facts matter. The science, on its own, is revolutionary enough. What she’s doing is clearly very tough on her. The week she visited my home she very nearly won the Nobel Peace Prize – it’s hard to imagine the kind of pressure the world has put on her shoulders. Hers is a unique expression from a unique person at a unique moment in history. Over and over she repeats that this movement for climate justice isn’t about her. It’s about everybody. The children on strike are not trying to inspire you. Or even impress you. They shouldn’t even have to do anything. The grown-ups, the literal adults in the room, should be acting on their behalf. Her actions are not divisive; they make perfect sense. It is the world’s adults, by denying the truth of what this moment requires of us, who are acting divisively.

Like no one before her, Greta has galvanised the world’s attention on the most important problem in human history. For this, she is regarded as both a hero and a villain, depending on your willingness to accept the blunt truths she tells. In a more normal time, world leaders would have taken the advice of scientists decades ago, when they first warned that the entire basis of powering our global economy was quickly leading us toward mass extinction. In a more normal time, a generation of young people around the world would not be experiencing “pre-traumatic stress disorder”, wondering if they would have a future at all. In a more normal time, Greta would have never set foot in my living room or played with my two boys.

After she and her father left, I realised her beautiful humanity is what makes her so dangerous to the status quo. I recognise this same quality in so many people in my professional and personal life. At times, I recognise it in myself. If we all share the same revolutionary humanity as Greta, then what’s our excuse for not embracing it?

Excerpted from The Future Earth by Eric Holthaus, reprinted with permission from HarperOne an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2020.

About the images

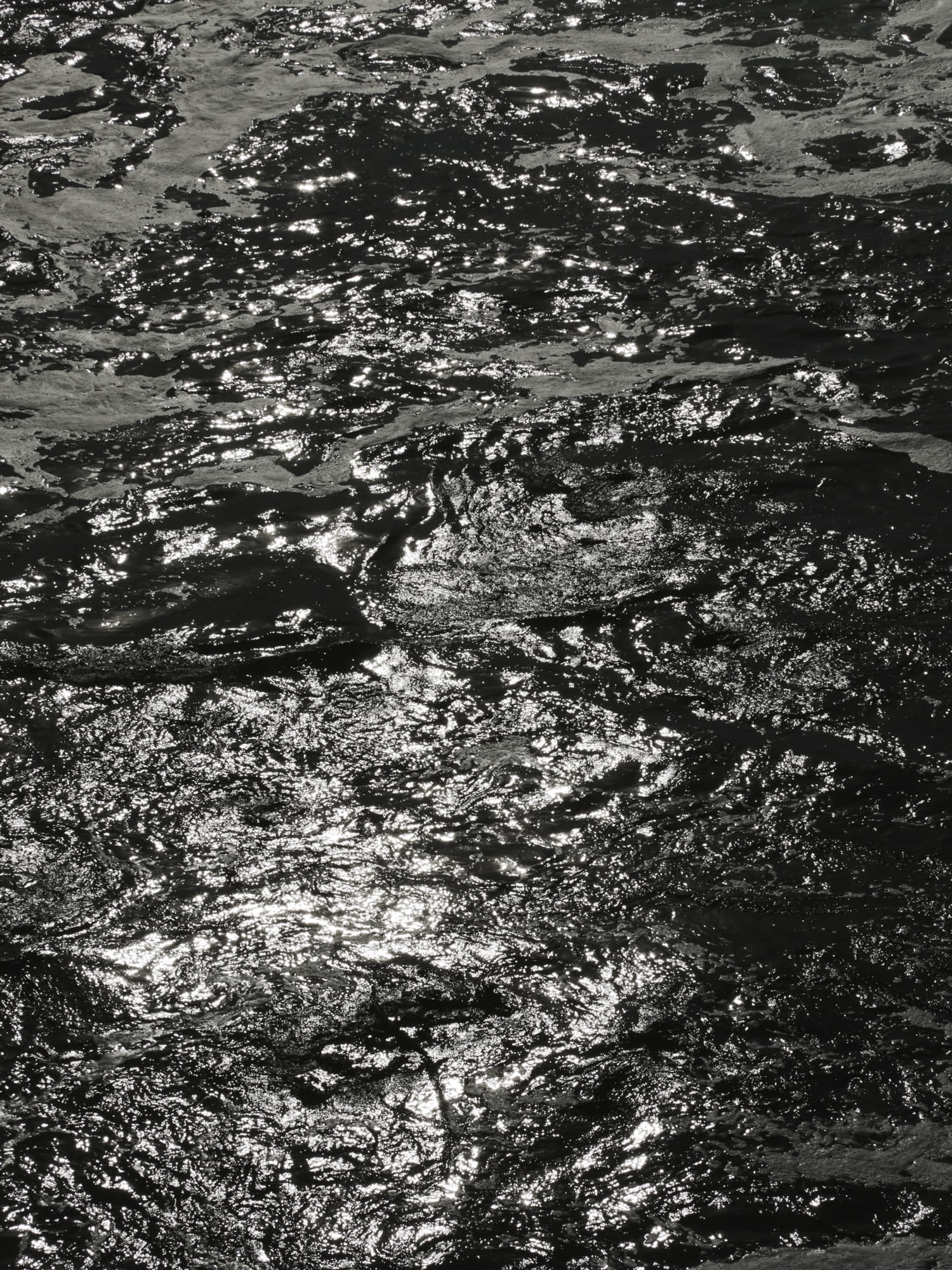

There is a hazy reflection of trees in the cloudy water and the water, in turn, reflects on the black, zipped leather shoes that seem to be going nowhere. When you look at this image from the series ‘Between Ourselves, Our Screens, And The Sky’ by Ryan Molnar you can imagine the scene to be set in a liminal space – transitioning between the physical and digital, hyper-connection and feelings of anxiety. His work touches upon difficult themes in a light and poetic manner.

About the images

There is a hazy reflection of trees in the cloudy water and the water, in turn, reflects on the black, zipped leather shoes that seem to be going nowhere. When you look at this image from the series ‘Between Ourselves, Our Screens, And The Sky’ by Ryan Molnar you can imagine the scene to be set in a liminal space – transitioning between the physical and digital, hyper-connection and feelings of anxiety. His work touches upon difficult themes in a light and poetic manner.

Dig deeper

In 2030, we ended the climate emergency. Here’s how

If words make worlds, then we urgently need to tell a new story about the climate crisis. Here is one vision of what it could look and feel like to radically, collectively take action.

In 2030, we ended the climate emergency. Here’s how

If words make worlds, then we urgently need to tell a new story about the climate crisis. Here is one vision of what it could look and feel like to radically, collectively take action.