Bread, I’ve learned, can be cruel. It will fill you up, but leave you feeling empty. “Bread hates us,” my mother used to say growing up, by which she meant: our bodies can’t process it. It makes us fat. But it’s all we want. Bread, she warned, didn’t love us back.

The historian Yuval Noah Harari goes so far as to blame all of civilisation on a lie sold to us by wheat. In his book Sapiens, Harari explains that the agricultural revolution was one elaborate con in which human beings thought we were domesticating grains in order to set ourselves free, but actually were consigning ourselves to a life of global drudgery that mostly benefited the wheat itself. “We did not domesticate wheat. It domesticated us,” he writes.

It stopped us in our tracks, forcing us into a stationary society so we could tend to its whims. Its imperfect nutrition led to a population boom that changed our species and the planet, and ushered in the globalisation that defines us now. It forced us to give up the healthy varied diet we’d enjoyed, which hurt our immune systems, while the labour to grow it broke our bodies. “This is the essence of the Agricultural Revolution,” Harari argues, “the ability to keep more people alive under worse conditions.” Wheat even, he writes, brought us pestilence and plague.

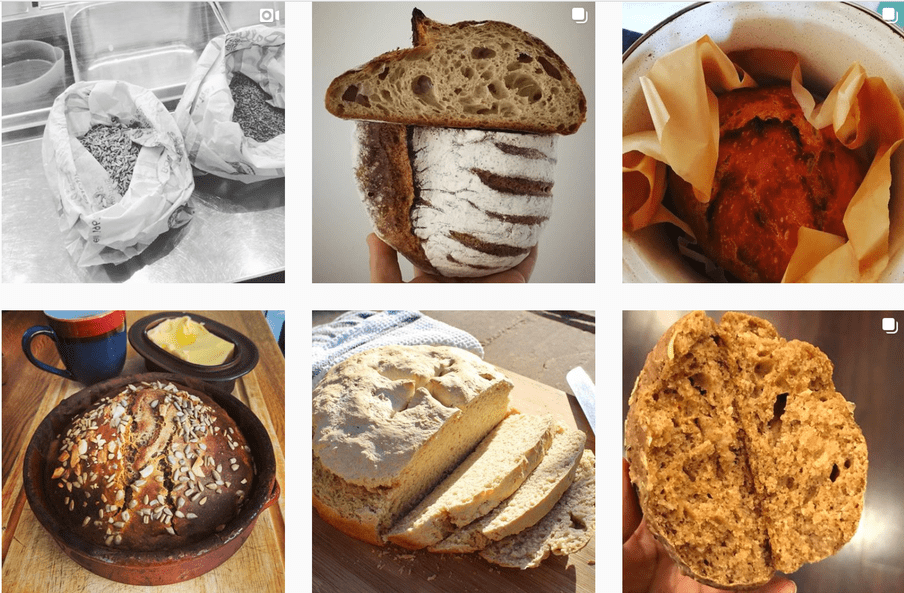

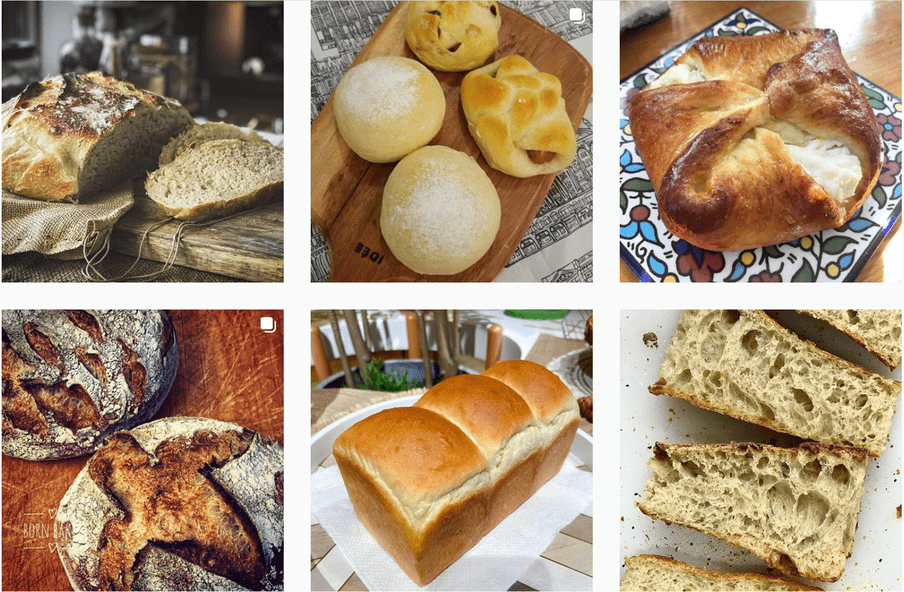

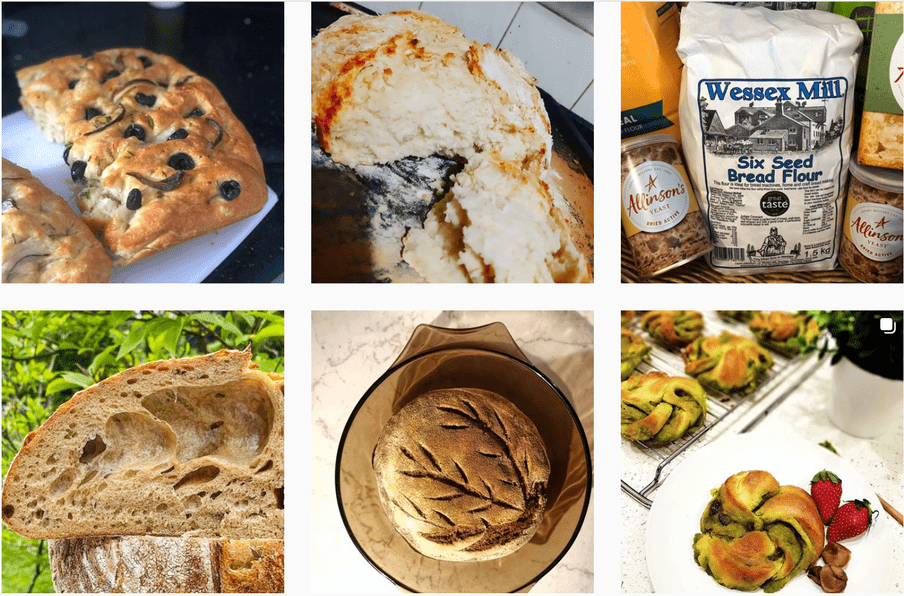

We cannot break bread together, but bread photos are everywhere

And so it is poetic, and perfectly awful, and maybe inevitable that right now, as civilisation itself – schools and businesses and supply chains and geopolitics – grinds to a halt in the face of a worldwide pandemic, that humanity would turn once again to the grain that made civilisation possible. We seek nourishment, and comfort. We seek routine, and meaning, and something we can count on.

“Today I have received three separate sets of unsolicited Sourdough pics. What the hell is going on?” the feminist writer Laurie Penny tweeted in early May. The answer was that bread, and all baked goods, have become a kind of ritualistic apotropaic plea, made separately on all corners of the Earth by humans sheltered in our homes fearing the same invisible danger, and then shared collectively on the magical devices that we use to bridge our confinement.

We cannot break bread together, but bread photos are everywhere. The loaves are huge and tiny, misshapen and perfect. They are crusty and blobby and braided and strange and every single one is some kind of incantation. A prayer to end uncertainty.

In a way, that’s what bread has always been: the slayer of doubt. Unlike berries you must gather and game you must hunt, bread is a sure thing. If you grow wheat and take the grain and grind it up and mix it with water and yeast and maybe some bacteria and, sure, yes, throw in some salt for flavour, you will get bread. It may not rise. It may not crunch. It may not even contain that much nutrition. But it will feed your family. Hell, you don’t need the yeast. Just throw that flour in with some water and cook it and you have a food.

These are the thoughts that went through my head two months ago when food shortages first hit the US and my job as the editorial director of a nascent technology publication was so busy and stressful that I felt I was drowning and my son was sent home from school indefinitely and my two cousins died of the virus, one after the other, and I just wanted to know one thing for certain: that I could feed my family. I fixated on flour. If I had flour, enough flour, then we’d eat. No matter what. No matter if we couldn’t leave our homes. Water from the tap, flour, oven, that’s something, right? That’s matzo, at least! The food of my people!

Wheat, thanks to our dotage, is one of the most successful plants in the history of the earth

But there was no flour to be found. The supply chains that society had developed to carefully ensure that my corner of San Francisco, California on the westernmost side of the United States always had just enough flour stocked on shelves seemed to have completely broken down. I searched in three stores within a few miles of my house, not wanting to venture too far and violate the shelter in place order in my city. No toilet paper. No eggs. No flour.

Already those with foresight and an earlier inkling of doom were parading their baked goods across Instagram, Twitter and Facebook, evidence that they could nourish themselves. My jealousy was boundless. They, the others, my friends and acquaintances, had flour. I had a baby and a four-year-old, mouths to feed, and I had none. I thought, OK, forget consumer markets, go to the source: the wholesalers. But they were sold out. OK, forget globalisation, I realised, go smaller. You can only count on the local community at this moment. Does California even grow wheat, I wondered? I had no idea. But we grow everything else, so we must, right?

Harari notes that wheat, thanks to our dotage, is “one of the most successful plants in the history of the earth,” covering 870,000 square miles. Miles that extend, it seems, into California, given the fact that a simple Google search brought up a handful of mills in the area. They, too, were sold out. It was 24 March. The Bay Area had been sheltering in place for only a week, and somehow it seemed the entire community, the whole nation even, had already bought all the flour.

From the beginning of the crisis, bread was calling us. Finally, at the bottom of the Google results for local mills, I found an artisan flour provider that wasn’t sold out. The only available sack was 50lbs. Could I handle that size? Of course I could!

As I waited days, I oscillated between shame (“that was silly, 50lb!”) and fear (“what if it never arrives?”) and the realisation that if it did arrive I would have to learn how to bake.

Yes, I must admit, I have never baked. Before the pandemic, if you asked me a random fact about myself I might say: I don’t bake. I sauté. I flambé. I roast. But I am not a recipe follower. I like to scan cookbooks and then go my own way. Yet, when everything I knew about the world seemed no longer to be so sure, even this defining character trait went out the window. I craved not only bread but the comfort of following instructions.

When the bag arrived, it was 20lb heavier than my first born child. He helped me lug it into the kitchen where it sat, unopened, for a week – a gaudy reminder of what began to feel like my extreme overreaction. That is until neighbours and friends began stopping by to trade for cups of it: we got toilet paper, cookies, eggs (blessed eggs!), a pre-mixed glass jar of Negroni cocktails.

When a colleague traded me a sourdough starter, I, like so many people I was “seeing” through my tiny window onto the world through my phone, became totally ensnared by its demands. A sourdough starter needs constant attention. Like my family, and our cats, and my ego, it must be fed and warmed, nurtured and pruned. It has highs and lows. Sometimes it peaks in the middle of the night, its potential missed.

“the woman who invented bread was just fuckin around w some yeast one day like dam better bake this bitch,” someone named meep wrote once in a tweet that I feel captures the magic of bread. According to the writer Cody Cassidy, yeast experts think the woman who first discovered leavened bread likely spilled beer on her dough and the results were a happy, bubbly accident.

The starter had me in its grip, yet I still hadn’t begun baking. Then, at the end of April, as I was settling into the routine of the pandemic, I lost my job – along with the colleague who’d given me the starter and half of the team I’d built – and it was finally time to bake.

How to bake a pandemic loaf

As the days lost all shape, the baking of bread gave them back some contour.

Split the starter in the evening so it’s perfectly active in the morning. After you wake up and feed the children and tell your husband everything will be OK, and make coffee, split some more to make a levain for your loaves. After you call the bank and ask if they’ll let you pause your mortgage payments for a few months, and apply for unemployment, and finally brush your teeth, the levain is ready and it’s time to autolyse your flour, which just means mix it with water. Now you have time to lie down on the floor and have a panic attack.

When that’s over, grind some salt in a mortar and pestle like the Naftufians who first domesticated wheat, really get your rage out, and then carefully sprinkle it over the dough. Then smooth your gooey levain that smells so sour over the top and if you cry that’s fine. It’s salt. Now mix it all together in your hands, your hands that every day until this day have typed words to pay for your life, have mixed bottles to feed your babies, have tickled your children, have caressed your love, have bloomed age spots even though weren’t you just young a moment ago? Those are the hands you use. And when it’s mixed, wait hours and hours until it triples in size.

You have time to have a drink. Catch up on emails. Call a friend and ask if there’s any news from their part of the world. And when it’s risen, split it in two and shape it and put it in the fridge overnight and in the morning bake it in a domed pot in the hottest oven you can manage. And slather butter on it for your children. Eat yours standing up listening to the jobs report on the radio, millions out of work. In 10 minutes, you’ll feel hungry again.

So far I have baked eight loaves. I follow the recipes to a T. I do not want to stray. Each loaf is so much work. Days of my life. I share images of the process with my friends on social media, and maybe they know these breads are therapy and prayers and maybe they don’t. I call the loaves my worry exercises. And by that I mean a way to exorcise worry from my life, and also to practise it, the act of mindful worry, attention to worry. Worry, which used to mean the winnowing away of something physical, and later turned interior, feels when I’m making bread like a peaceful, intentional process of gnawing through the thicket of uncertainty. I do not know what is on the other side.

I do not know when my son will go back to school. I do not know how many people will die. I do not know when I will get another job. I do not know how I will pay for my mortgage or where we will live if we can’t afford to live here, in this home we have made, in this community that we’ve chosen, and in which our lives now feel trapped in so many physical and figurative ways. But I know I can make bread.

Now I follow all the bread people online. They are now my people. There’s Seamus Blackley, who invented the Xbox and has a pandemic starter made from 4,500-year-old yeast he scraped off ancient pots in anthropology museums. There are the strangers around the world who tweet to Blackley and each other using the hashtag #yeastmaster. There’s challah Instagram, and boiled bagel Instagram, and so many sourdough starter Instagrams. There’s baking Twitter where feminist writer Roxane Gay turns for tips on how to develop the perfect cookie. And then there’s naan made by a friend in India, and chapati made by another in Kenya. Our friend in the UK has perfected a sandwich loaf, while in Argentina, friends are baking cake. The pictures shared on social media or in direct messages remind us we’re all in this, whatever this is, together.

Before it ends – and it will end – I’m planning my next loaf. I start it tonight. Now I know what I’m going to be doing for the next three days, and right now, that’s about as much as I can ask for.

Dig deeper

The real reason we’re ad free

In a series of short videos, managing editor Eliza Anyangwe and founding editor Rob Wijnberg answer the seven most frequently asked questions we get about The Correspondent.

The real reason we’re ad free

In a series of short videos, managing editor Eliza Anyangwe and founding editor Rob Wijnberg answer the seven most frequently asked questions we get about The Correspondent.

You used to have hobbies. Now you have to have an obsession

Detoxing, house plants, healthy eating – we’re obsessed with obsessions. Obsessions promise perseverance, focus and success, without us having to do it all ourselves. But what do we stand to lose as a result of this modern addiction?

You used to have hobbies. Now you have to have an obsession

Detoxing, house plants, healthy eating – we’re obsessed with obsessions. Obsessions promise perseverance, focus and success, without us having to do it all ourselves. But what do we stand to lose as a result of this modern addiction?