Twenty-eight years ago, Susan Sontag – writer, activist, public intellectual – was interviewed on stage in New York. She spoke about writing, and about all those people asking her how they could become writers themselves.

Her answer was simple: "You have to be obsessed."

Sure, Sontag said, even non-obsessed people can write. There are also amateur painters and amateur musicians, and that’s all well and good. But if you want to be a serious writer, if that’s the life you want to live, then obsession is the only way to go about it. Writing, Sontag said, "is self-enslavement. Obviously."

Read this story in one minute.

Why writers need to be obsessive

"Obviously." That adamant certainty was typical of Sontag, but she was by no means alone in her conviction that obsession makes the writer.

According to another celebrated author John Updike, Sontag’s contemporary, it is "the willingness to risk disproportionate excess in the name of your obsessions" that distinguishes artists from mere entertainers.

British author Zadie Smith once divided writers into two categories – the micro managers and the macro planners – who are united in a shared "obsessive attention" to their craft.

And Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgård has enthralled the literary world for almost a decade with a magnum opus so extensive he could never have created it if he had not, obsessively, turned every detail of his life into fodder for his craft.

No wonder David Remnick, editor-in-chief of the New Yorker, only wants to know one thing when looking for new writers: if they have an obsession.

Artists, athletes and designers too

Within psychiatry, obsessions are defined as "upsetting and unwanted thoughts, images, and impulses that constantly recur, sometimes throughout the day and night". People who end up with a diagnosis of obsessive compulsive disorder must learn how to curb those obsessions. That sounds deeply destabilising, and yet apparently you can’t do without an obsession if you want to write a book.

What is true for writing is true for other callings too. Artists, athletes, entrepreneurs, designers: if they’re not obsessed, you’ve probably never heard of them.

MMA fighter Conor McGregor, for instance, likes to say he’s not talented: he’s obsessed. Photographer Hans Eijkelboom has been said to have "an obsession with mass fashion", while Aitor Throup, creative director of the jeans brand G-Star RAW, has a self-proclaimed "obsession with trousers".

Obsession, the Economist proclaimed a few years ago, is what fuels Silicon Valley. Profile after profile describes former Apple CEO Steve Jobs as an obsessive micromanager (who made life impossible for the people around him).

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s obsessions include China, livestreaming and "killing the smartphone".

And Justine Musk, ex-wife of Tesla founder Elon Musk, once wrote that anyone who wants to become as wealthy as him needs to do three things: "Be obsessed, be obsessed, be obsessed."

We live in the age of obsession

These days, even for lesser mortals, obsessive tendencies seem to be the rule rather than the exception.

Search for #obsessed on Instagram and you’ll get more than 10 million hits revealing modern humanity’s obsession with, among other things, dogs, cats, six-packs, Stranger Things, plants, babies, knitting and their own butts. You’ll also find Instagrammers calling on their followers to become, like them, "obsessed with health".

It should be easy to imagine a world in which "healthy" and "obsessed" are not synonymous. But on social media, no one ever tires of declaring their #obsession with smoothies, with 80 day "obsession workouts" and yoga poses that put curves and sleek muscles in just the right places, with the bodies and discipline of athletes who serve as role models.

It should be easy to imagine a world in which ‘healthy’ and ‘obsessed’ are not synonymous

The fit girls, the juice junkies, the detox lovers: obsession is what defines them, what they use to define themselves – all in the name of health.

More examples? "If he isn’t obsessed with me, I don’t want him," says one Instagrammer. The Netflix series You revolves around a bookstore manager who becomes obsessed with a woman he meets in his store. Chef’s Table, another Netflix original, featured a chef who is "obsessed" with bread. News website Quartz doesn’t have beats; it has "obsessions". And 25 years after its original launch, the sexiest advertising campaign ever made is still the one with which Kate Moss put a Calvin Klein perfume on the map – a perfume called "Obsession".

When Elle released an "obsession issue" a few years ago, a columnist sheepishly confided to her readers that she was "obsessionless in an age of obsession".

So, just how did we end up in this age of obsession?

The evolving meaning of obsession

When Daan Roosegaarde, the most celebrated designer in the Netherlands these days, was interviewed on the radio a while back, he cheerfully talked about the mess – debris from broken satellites and the like – that floats around in the universe. Roosegaarde wants to clean up that mess.

"I have no idea how just yet, but we’re going to do it." It was, he confirmed, his "latest obsession".

"You’re always a victim, or a kind of prisoner, of your own ideas," he added. You could almost hear him smiling as he said it – this was the most enjoyable imprisonment ever.

Where Sontag talked about slavery, Roosegaarde spoke of victimhood and imprisonment. That’s appropriate: "obsession", from the Latin obsessio, was originally a term of war.

In his delightful book Obsession: A History, historian Lennard J Davis explains that in ancient times, the conquest of cities happened in two stages: obsessio and possessio. During obsessio, a city was surrounded by hostile forces, but the core, the citadel, was still intact. Once possessio was reached, the enemy had breached the city walls and captured the heart of the city.

In the Middle Ages, the term was used to refer to a different kind of possession as well – one in which the attacker was the devil, the city was a person possessed, the soul a kind of citadel. Those who were obsessed had been overpowered by evil forces, but were not yet fully possessed. An obsessed person knew they had no control over certain behaviours or thoughts – they knew that these things happened to them, and did not originate within them. However, all along, they were aware of their own situation: #obsessed.

In the modern, more medical definition of obsession, which took root from the late 17th century on, this ambivalence was retained. The patient with compulsive thoughts was both slave and victim at once, and was well aware of their own condition.

It’s not surprising, Davis writes, that during the 18th century, obsession became secularised and democratised. The period was characterised by industrialisation, by the increasingly precise compartmentalisation of time, space and work, and by specialisation and professionalisation.

An obsessive attention to detail and precision became pervasive. Previously, with his wide-ranging palette of knowledge and interests, the "Renaissance Man" had been held as the shining ideal; he now gave way to the expert, someone who had a singular, crystal clear focus.

Obsession, in short, seemed to be everywhere. And it was always a double-edged sword: if you had the misfortune of having too much of it, you’d be a psychiatric patient. If you had just the right amount, you were the expert studying that patient.

What defines the modern obsession?

If every era gets the type of obsession it deserves – from war tactic to religious phenomenon to medical disorder – then what’s the meaning of obsession today, in this "age of obsession"?

One could argue, of course, that the term’s popularity is simply a matter of hyperbole, nothing more and nothing less. That when "hobbies" turn into "passions" and every experience is labelled "epic", it follows that what were once considered "interests" should now be called "obsessions".

One could also argue that the extreme, fanatical nature of obsession is a perfect fit for a performance-driven society that prefers its residents to be ambitious, energetic, and inspired on demand. The marathon runners, the sprinters, the people who pull all-nighters: those are the heroes of our culture.

But neither explanation takes the contradictory and therefore profoundly revealing nature of obsession into account. To be sure, the age of obsession has everything to do with the desire to succeed. For years, best-selling works in popular psychology have been spreading the gospel that a combination of passion and perseverance is a major predictor of success – even more important, perhaps, than innate talent. And what is obsession, if not the superlative form of passion plus perseverance?

Technology also has a hand in the flourishing of obsession. After all, collective obsessions – hypes – are made possible in part by social media, by the fact that you have timelines and feeds that make it seem like everyone cares deeply about the same topic. And that makes it all too easy for you to behave like Alice in Wonderland, falling down click holes.

But at the same time – and this is the irony of it – the idea of obsession today seems to serve as a prophylactic, shielding us from the enticements of those same technologies – the lure of social media and the siren song of the smartphone.

Or, as a colleague put it when I mentioned I was writing a story about obsession: "I wish I were obsessed. Then I wouldn’t be so distracted all the time."

That is to say, the emergence of obsession as a cultural keyword, a hashtag, coincides with a growing awareness of the more unpleasant side effects of technological progress – more precisely, of the technology-facilitated distractions that increasingly weigh all of us down.

The backlash is coming from both within Silicon Valley and outside it. Books with titles such as Irresistible and Hooked, reformed Silicon Valley pioneers who have seen the light, and every self-respecting self-help coach will tell you that smartphones and social media are addictive (or "habit-forming") and detrimental to our ability to focus.

Technology also has a hand in the flourishing of obsession. After all, collective obsessions are made possible in part by social media

Sure, there’s nothing new about the idea that the media distract us, but smartphones have put that powerful distraction into our hands and pockets, and we seem unable to resist its allure.

We can’t read an essay without checking our phones five times, Netflix auto loads the next episode for us, and we are forever interrupted by vibrating, flashing, beeping notifications, precluding any possibility of "flow".

And if this addiction to technology threatens us all, a different type of addiction – an obsession – seems to offer a way out. After all, an obsessive will keep working no matter what. (Indeed, while Cal Newport was working on his best-selling book Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World, he posted a blog in which he contemplated "obsession as a productivity tool".)

Obsessives will be dedicated enough to ignore the little red dots announcing new notifications, to abandon the "infinite scroll" of Twitter and Facebook, to stay inside and pull an all-nighter, hit the gym until they’re toned, eat avocados until they’re slimmed down to a mere sliver of themselves.

Why obsession is so appealing (and dangerous)

Obsession’s appeal today has to do, most of all, with a feature that was embedded in the earliest definitions of the word: that of being surrounded, of obsession as an external influence that comes in and overpowers you.

That feature means obsession transcends the individual – and that’s exactly what makes it so desirable. After all, in this lonely 21st century, we’re primarily expected to rely on ourselves above all else: autonomy, initiative and "realising your full potential" are the modern commandments.

Such profound self-reliance is exhausting, possibly even isolating. And obsession offers an escape: it promises perseverance, focus and success, without us having to do it all ourselves – it’s like having someone give you a ride home when you thought you’d have to walk the whole long, lonely way on your own two feet.

Cultivating the perfect six pack, cleaning up the universe, binging on all eight seasons of Game of Thrones, unleashing a Tesla fleet on the world: an obsession not only gives us the discipline needed to pull it off but also provides us instantly with direction, purpose and meaning, however superficial or random.

Obsession is fuel, free discipline and a sense of significance; it is a soothing balm for the modern soul.

At least in theory.

But in practice, the desire for something that takes possession of us, an external influence that overwhelms us and drives us forward, is accompanied by a powerful urge to control that thing, to make it available at our beck and call – to consume it, almost.

Take Justine Musk, who, when she pontificated that the secret to success was obsession, added: "If you’re not obsessed, then stop what you’re doing and find whatever does obsess you."

Obsession offers an escape: it promises perseverance, focus and success, without us having to do it all ourselves

Or you could take Ritalin, which is basically a kind of obsessive focus in pill form; it’s prescribed extensively to children and adults with attention deficit disorder (ADD), but also frequently used by students, writers and researchers who don’t have ADD. You could call it self-medication – or you could call it obsession on demand.

The contradiction between the desire to be overwhelmed on the one hand and the urge to be in control of that overpowering force on the other shows that the mythical power of obsession is exactly that: a myth. You could call it funny, if only it didn’t have such a dismal flip side.

Because glorifying and embracing obsessions and insisting they’re vital to success automatically disqualifies anyone who doesn’t want to live an obsessive life – or one who simply can’t. It trivialises the suffering of people with obsessive compulsive disorders or related pathological obsessions. And it makes us forget that obsessions, when seen through their lenses, are more likely to have negative fallouts than heightened productivity.

Indeed, the Canadian psychologist Robert Vallerand has shown that obsessive passions often have destructive side effects. That’s because they come with the kind of rigid perseverance that, for instance, causes die-hard cyclists to climb on their bikes, even in winter, with sub-zero temperatures and 20cm of snow.

It also drives obsessed gamblers to keep gambling despite the unbearable pressure it puts on their finances and relationships. And leads obsessed dancers to keep dancing, even when they’re hurt, ultimately causing exacerbation and more damaging injuries.

Obsession as a recipe for health, wealth and happiness? Ehm, no.

Our true obsession

The fact that obsession continues its hold on us despite its many downsides has to do with its overwhelming, overpowering aspects. As such, it testifies to our longing for something greater than ourselves.

And above all, it’s a testament to how this pursuit of something bigger than ourselves has led us astray.

Obsessions are prisons that hold us captive, disguised as deliverance that sets us free. They allow us to step outside our individual, solitary selves, but without us having to actually connect with one another. They allow us to toil away, while others grind to a standstill under the influence of technological distractions.

Obsessions are prisons that hold us captive, disguised as deliverance that sets us free

And they give us a sense of direction, without requiring us to really think about its significance or value.

That’s pretty ironic – or, depending on your mood and predisposition, sinister. At the same time, I can think of no better symbol for the paradoxical, twisted nature of the times we live in. And on some level, I suppose I find it reassuring to know that most of us probably aren’t really, truly obsessed with cats, "bowl food", smoothies or Gigi Hadid.

It’s soothing to realise that the only thing we’re really, truly obsessed with may be obsession itself. And to see that it is precisely this obsession with obsession that unites us in the end. That elusive, mercurial, powerful, promising, ominous obsession – go ahead and try not to become obsessed with it.

About the images

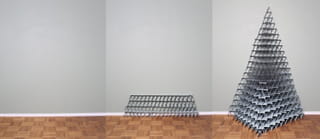

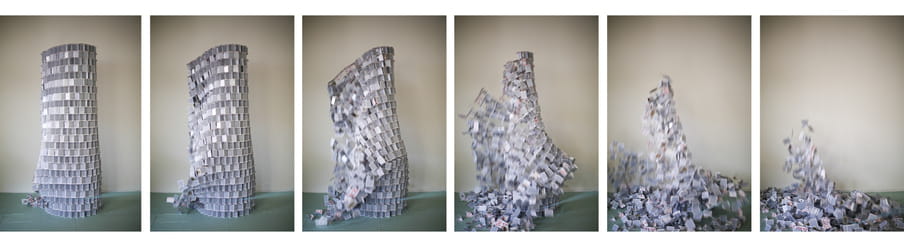

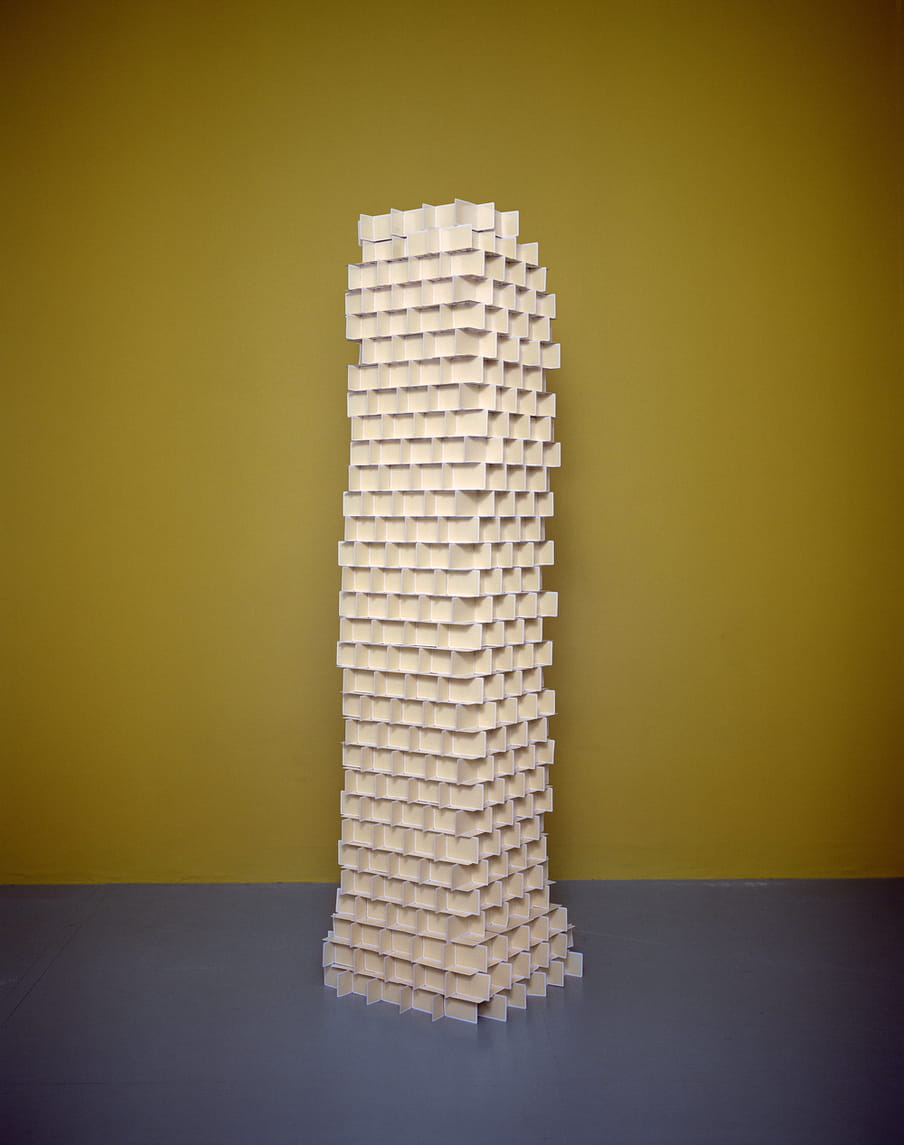

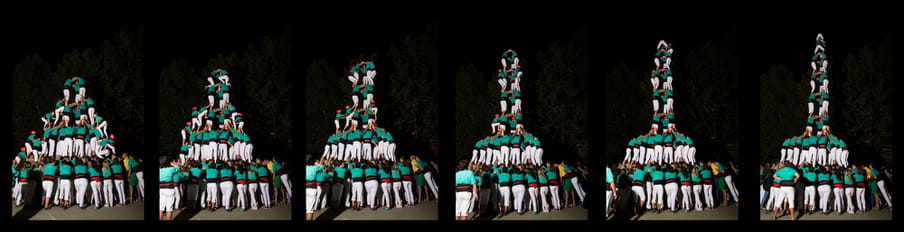

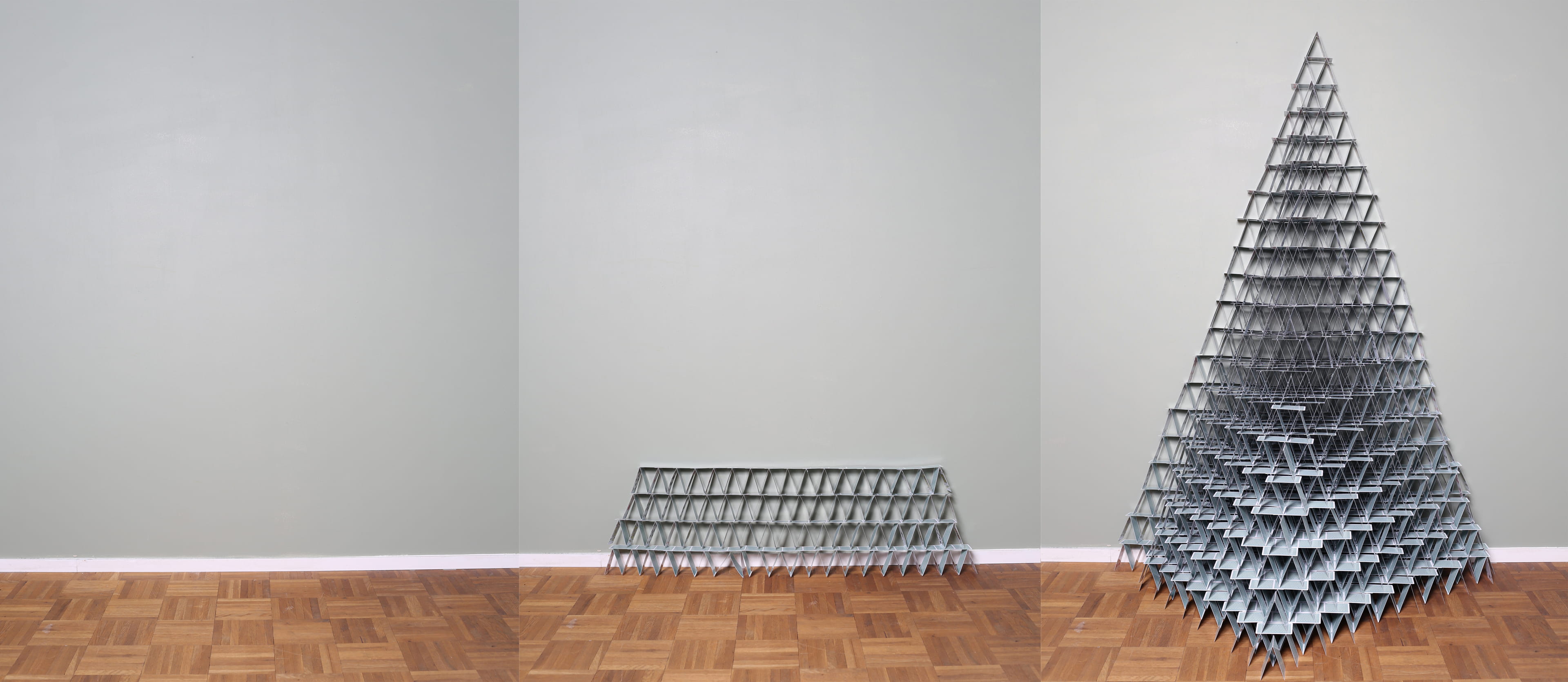

Nowadays, there seems to be no room for failure. An unproductive human being is an unattractive human being. With the series Towers, Lana Mesić claims the right to spend and waste time on a "useless" obsession. It probably won’t solve world problems or even stand the test of time. The towers will fall and all that will remain is proof that they were once there.

About the images

Nowadays, there seems to be no room for failure. An unproductive human being is an unattractive human being. With the series Towers, Lana Mesić claims the right to spend and waste time on a "useless" obsession. It probably won’t solve world problems or even stand the test of time. The towers will fall and all that will remain is proof that they were once there.

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Dig deeper

How we turned into batteries (and the economy forces us to recharge)

Energy has become modern society’s holy grail, but what if we don’t want to spend our limited time on Earth constantly recharging and draining ourselves? In an age of punishing pressure to be productive, saying no is the opposite of negative.

How we turned into batteries (and the economy forces us to recharge)

Energy has become modern society’s holy grail, but what if we don’t want to spend our limited time on Earth constantly recharging and draining ourselves? In an age of punishing pressure to be productive, saying no is the opposite of negative.