My father died within a week of our last extended phone conversation. When we spoke, I had been in the middle of recounting an event from my life when he interjected so softly that I barely heard: “I fell down.”

I paused, startled and unsure whether he had spoken at all. “What did you say? You fell down?”

But then he denied it, said I’d misheard, that he was fine, it was a bad connection. We were oceans apart after all: he in Ethiopia and me in the US, technology often making our distance audible. I’m fine, he kept repeating. But I was shaken, and as soon as we hung up, I scrambled to call my mother and brother, and gradually the truth came out: he had fallen.

Two days later, he was bedridden, nearly incapacitated by pain. The distance between us, always significant, seemed to expand and balloon as I tried to speak to him, tried to get family members who were with him to describe his symptoms accurately. I attempted to decipher what was truth and what they were protecting me from. “He’s going to be alright,” they said. “Don’t worry, he’s seen a doctor, they’ve taken tests, we’ll get the results after the weekend.”

A few days after that, just past midnight, I found myself struggling with the most violent hiccoughs I have ever experienced. They convulsed my body as if a heavy fist were trying to pound through my ribs. Surprised, I stood up from the work I was doing on my novel and rushed to get a glass of water. My husband came to stand next to me, alarmed by the intensity of the spasms. I gulped water, then air, then tried every other trick I could think of to make them go away. Finally, gradually, they subsided. I went to bed soon after that, exhausted, only to be woken a few hours later, in the early light of dawn, when my husband’s phone rang.

In Ethiopia, the death of a loved one is generally conveyed to distant family by someone connected, but not necessarily bound by blood, to the deceased. These crushing blows can be cushioned, the belief goes, if conveyed by someone who is capable of relaying the news with some composure and control. So when my husband’s phone rang in those early hours, I braced myself. As his voice shook and he reached for my hand while still on the phone, I could feel myself already tipping into that space I would recognise later as mourning. When he hung up the phone and turned to me, rendered mute by the enormity of the news he had to convey, I said: “Say it,” even though I already knew what had happened: my father was dead.

Hiccough: medical term, singultus; Latin, singult: a sob, a speech broken by sobs.

I’ve lived apart from my family for longer than I’ve ever lived with them. I can point to many reasons: the 1974 revolution in Ethiopia, their desperate concern for my safety, their belief that in the US everything would be better. Beneath it all was the unspoken certainty that somehow we would manage the distance between us, that it was a space we could fill with love and phone calls, flights and visits and memories. We envisioned distance as simply that: oceans and kilometres that could be bridged by words, by emotion, by sheer will and the dogged illusion that love conquers all. But after my father died, this occurred to me often: that there are tender mercies the world offers us, but distance is a cruelty it yields in surplus.

My father refused every plea to be admitted to hospital for observation and pain relief. He died alone in his tiny studio which sat towards the top floor of a high rise, in the centre of one of Addis Ababa’s busiest squares, Meskel Adebabay.

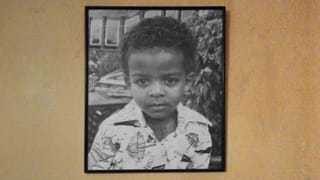

In that small, spare home were all the possessions he owned in this world, mostly family pictures. Three large photographs dominated the walls: two black-and-white ones of my brother and I as children when we lived in Nairobi, before migrations and separations; and another photo of himself as a much younger man.

Beneath these large photographs were smaller ones that sat framed on a shelf. My father had been found curled on his side with his head resting on his hands, facing that wall and shelf. The woman who came to clean his apartment had stepped out while he was still alive, then returned shortly after to find him dead. “Tranquil,” my mother said, as if he’d just fallen asleep. My father who often boasted of his perfect vision would have been able to see even these smaller pictures clearly: he and I on my college graduation day hugging and jubilant; my brother in grade school; my middle school photo; one of all of us together.

Beside me, my cousin comforted my brother, but I could do nothing but stare quietly at the photos and wait for my mind to catch up with the moment, realising that the last thing he saw before he shut his eyes forever was my brother and me, in those photographs. He had been staring through time, past the distance, and rushing towards those years when we were once in the same place.

A dream: my father is falling from the sky. He plummets towards a barren, desolate landscape while I rush towards him, too far away to stop his crashing contact with the earth.

It is said that a person’s life flashes in front of them just before they die. That there is a visual acknowledgement of our lives at the very end, and even long forgotten moments rise up in a series of images before they – and we – fade to black. Our last vision of this world is ourselves. Or rather, the memory of ourselves.

According to this adage, we do not leave this world before we travel back to gaze on our beginning. And all of this will occur through pictures. Images will guide us to the end and through them, we will inhabit a space that is both past and future, both living and dead, before we travel to that other place unmeasurable in distance.

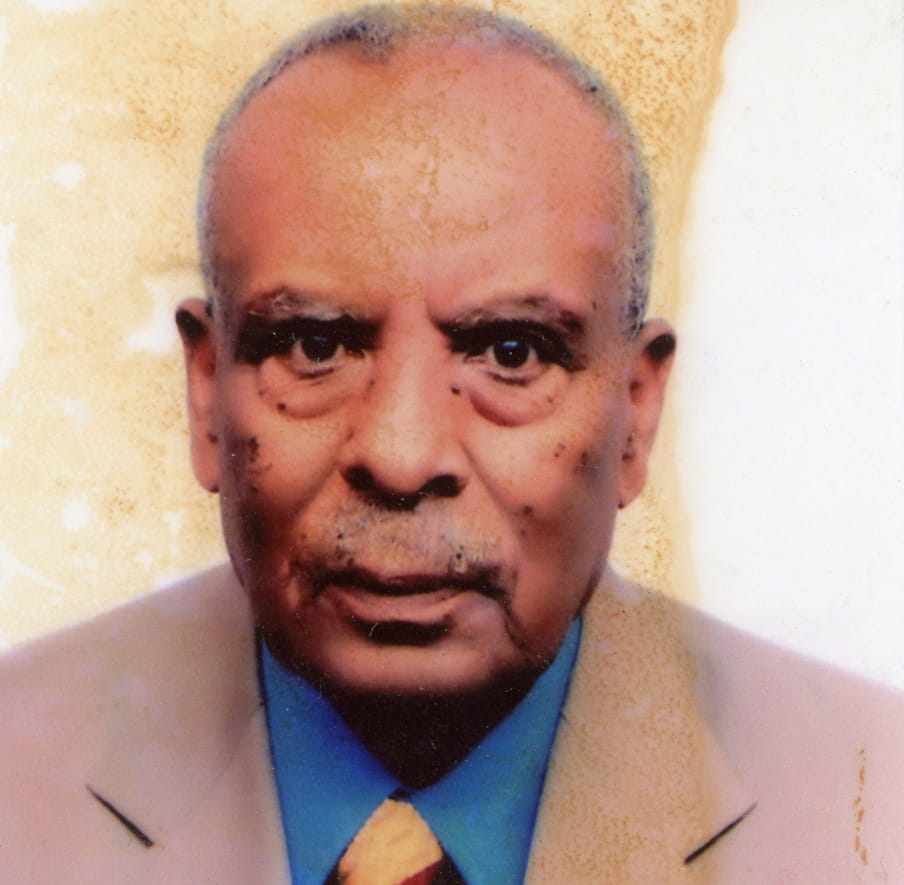

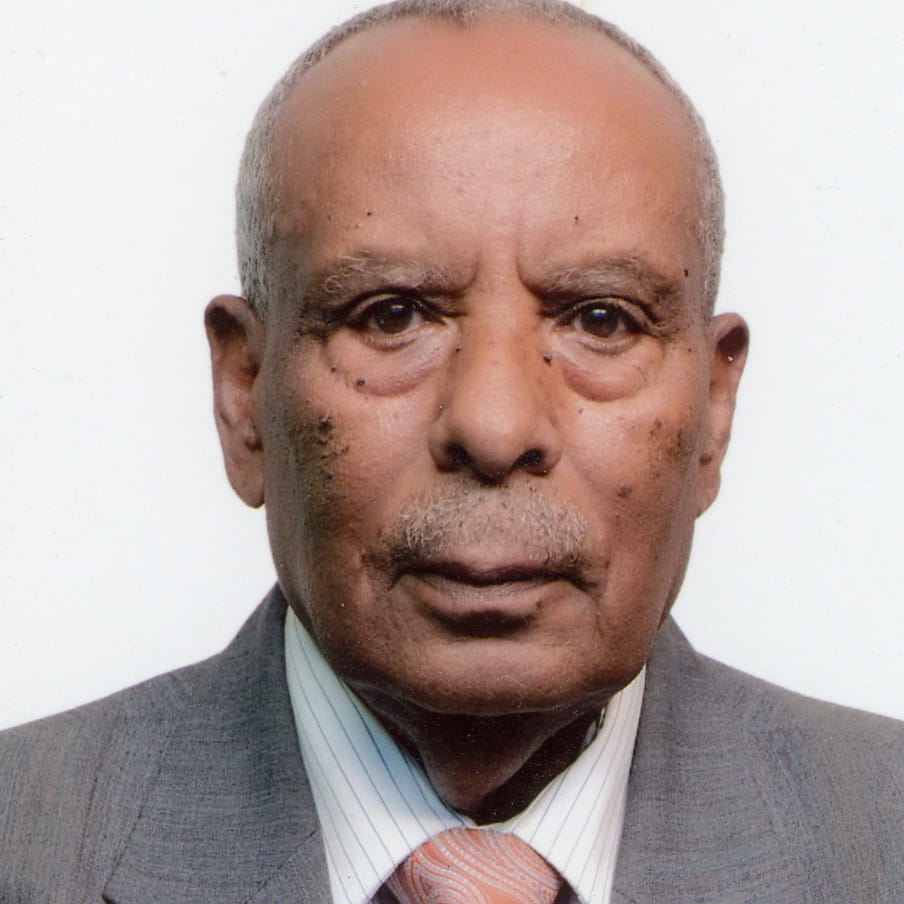

If this is true, then I would like to believe that one of the last images my father had of himself came from his favourite portrait, the one that hung in his apartment, of him dressed in his Ethiopian Airlines uniform. The one where his expertly knotted tie rests against his crisp white shirt. Perfect round buttons, polished and smooth, give off a subtle glint. He is looking off to the side, a smile threatening to overtake his solemn expression. His features, slender and free of wrinkles, are handsome. His high cheekbones are prominent. His large, liquid eyes are turned up with that hint of a smile. He is assured and relaxed, as if he is aware of the camera but also focussed somewhere else, beyond that studio space. This is a picture of a man caught between emotions, of a young and energetic subject waiting to pivot out of an imposed seriousness into natural mirth: all of it framed by the camera.

I have a copy of this photograph. It is a tiny picture, the studio portrait shrunk small enough to fit into my hand. The edges are bevelled, delicately scalloped like fine glassware. The paper, creamy and textured, has a thickness and weight of a bygone era. The image is smooth, almost strangely free of any lines around the mouth, the forehead, the eyes: all those markers that speak of time and experiences lived.

I can no longer remember when he gave it to me. It might have been on one of my visits to Ethiopia. Or on one of his to the US. I know for certain that it was a casual gift – one out of many copies that he owned – and I’m sure that I accepted it as graciously, and casually, as it was given. Back then, it seemed to simply depict the many decades and events that separated him from his younger self, and I treasured it for the memories I knew it held for him. But as the years passed, and the distance increased between that younger man and my ageing father, I could not look at that photograph without an overwhelming sense of impending loss, and sadness about the vast oceans that separated me from those I loved.

A memory: proudly spelling for my father the first English word I’ve learned to write, T-H-E. He bends down to kiss my cheek then repeats it with me again and again. “So you won’t forget,” he says.

Here is another image: this one, a photograph of a European shoreline, one of those that serve as a boundary between despair and possibility. The beach is littered with debris: water-logged prayer books and Bibles, cracked plastic bottles, torn shoes, hastily discarded clothing. In the midst of this: a heartbreaking number of photographs: bloated, torn, faded scraps left behind to disintegrate in the sun and sand.

If you asked me when I saw this picture I would tell you it was years ago, in Lampedusa, in Rome, in New York City, in Berlin. I would also say it was just yesterday, here at my desk in Zurich. It was in Ethiopia, watching television in my father’s apartment. The particulars of that moment have disappeared but what I have, still, is the memory of that sighting and how I felt something fold inside of me and curl tight as if for protection.

Writer and critic Susan Sontag called photographs a “mournful vision of loss,” and philosopher Jacques Derrida said that photography is a mourning for a present that is no longer there. What is captured in a picture, they imply, simultaneously becomes a marker of that present time and a commemoration of the past.

While photographs are memento mori, what if they’re also much more? What if they are evidence of what we want to imagine will continue to live – despite the wreckage that distance and time inflicts?

An image holds a disappeared moment still, freezes it so we can come back to it in the future and remember what has been lost. The very act of taking a photograph is a wilful and naïve attempt to keep a moment intact and immobile. A photograph is the evidence of our determined and futile attempts to defy time, to always be here and there, to be alive. And yet, it is argued, every photograph confirms that we are continually in a state of loss. We are constantly alert to those fleeting, fragile moments we wish we could hold on to forever, even as we know it is impossible. Our world is full of mournful visions.

But those photographs on the beach, as fragile as the one my father once gave me, some as old as his, seem to be a silent testament to something larger than their premature destruction. While photographs might be memento mori – portable reminders of our inevitable death – what if they are also much more?

A friend who once made the journey from Ethiopia to Libya on his way to Europe told me he made sure to pack a few of his most treasured family photographs. This is a small detail that I cannot get past: those who leave often try to carry with them some part of those who stay behind. To slip a photograph into your bag as you begin an unfathomable journey is an act that is less about mourning and more about a bold attempt to defy the realities of migration and distance. I imagine my friend with his photos in one of the detention centres that dotted the route to Libya, trapped and frightened – when life itself is an astounding vision of loss, how does that alter the ways a photograph is seen?

Perhaps, in times of crisis or pain, photographs which once commemorated a particular time now unfold and expand to represent something else entirely. Perhaps the temporal distance inherent in a picture and the futility of our desire to relive certain moments, both shrink when life itself presents greater distances, greater futilities, and also, greater hopes.

Maybe a photograph does not necessarily lock us into loss. Maybe it does not bind us into a visible acknowledgement of our many frailties and vulnerabilities. What if, instead, a photograph is evidence of what we want to imagine will continue to live – despite the wreckage that distance and time inflicts?

A memory: my family at a studio for a portrait. My father and I are trying to keep our gaze on the camera and follow the instructions to be still. He is also trying to maintain a solemn expression, but seeing me grinning we collapse into laughter and ruin the shot.

In the days after my father’s death, I watched my mother and brother sift slowly through a box of my father’s photographs. In it, piles of memories, of our shared moments, of days that I could not recollect but had experienced. My mother took out a short stack of images and gently shuffled through them. They were studio portraits of my father taken on several different occasions.

In each, he is dressed in a suit, staring straight into the camera, as if nothing else holds his interest. He is serious, his mouth firm. In these pictures, time weighs on his features: the wrinkles slide from the corner of his eyes then disappear into the natural slopes of his face. My mother handed me four to take back to New York with me. I looked down at them. Inside my chest, a dull pain. Even as I wanted myself to believe that he was still alive, I understood what lay ahead. A photograph could not change that.

Yet something strange happened once I returned to the US from the funeral. It was hard to distinguish the distance that had always separated me from my family from the concrete fact of my father’s death. It was almost impossible to tell which kind of loss I was experiencing, when I had learned so long ago to accommodate the layered grief that migration stamped onto my life. And on those birthdays and holidays when distance camouflaged reality and I forgot my father was permanently gone, on those special occasions when I waited for his call then had to remind myself it would never come, I reached for those tiny portrait photographs and held them in my palm. They seemed in those moments to be my most precious possessions, as delicate as a human body. I stared down at his face, those features of an aged man, and waited for truth to settle back into place.

This happened often. For years, until my grief started changing shape. I learned not to wait. I learned how to live with the permanent silence death invokes. I was moving forward and that was leaving room for other ways of remembering, of travelling with him into the years of my own life.

And even though I dream of my father, still – visions of shattering falls and desperate, unheard phone calls – when I wake up, I know I have those pictures that he left behind. They offer me comfort and they speak to me of the profound and complicated life they represent.

My father took most of our photographs when my brother and I were children. He did it with a camera he later gave to me, one that I have taken with me every place I have moved.

In the first days of lockdown, when the global pandemic sent much of the world into isolation and separated many of us from our loved ones, as news started to spread of people dying alone and funerals held by video, old anxieties started to resurface.

“This reminds me of the revolution,” a friend of mine from Egypt said. “The curfews.”

Memory can be a formidable ally. Light enough to be taken on a fragile boat towards a new life, and sturdy enough to endure the dizzying, cruel separations of this current pandemic

Having experienced the early days of Ethiopia’s 1974 revolution, I felt I understood. Covid-19 had sent the world into a kind of exile. It had done to us all what intense poverty and oppression, wars and political conflicts, have been doing to millions of people for so long: it forced us to take refuge in the safest places we could find. It separated us from those we loved, and for many, it forced a reckoning with grief across unimaginable distances.

Without the opportunity to comfort or embrace a loved one, without the chance to be present in their suffering or as they breathed their last, photographs have become some of our most powerful reminders of life as we knew it before, with them. Perhaps they have also taken on added weight as a potent declaration of what we will – what we must – bring with us when we enter back into the world.

In their ability to box out distracting realities and present idealised representations of our experiences, our pictures could symbolise the kind of future we want to imagine is possible, after all of this. If a picture is an attempt to freeze a fleeting, dying moment, then maybe inherent in that attempt is the stubborn refusal to believe that our good moments die at the point of contact.

Memory can be a formidable ally. Light enough to be taken on a fragile boat towards a new life, and sturdy enough to endure the dizzying, cruel separations of this current pandemic. Those photographs that we bring along on this journey, whether on a phone or on paper, can form the bridge that carries us back and forth from here to there. Maybe we are not just trapping ghosts in every image that we take. Perhaps every photograph carries within it a defiant insistence that what we are looking at instead is a vision of hope.

Hear Maaza Mengiste live on 11 June at 16:00 GMT!

Register your interest to attend a virtual panel with Maaza and other creatives from across the African continent, by filling in this form. We’ll send you joining details, as well as the names of the other panelists, closer to time.

Dig deeper

Who’s afraid of loneliness?

With social isolation measures confining many of us to a company of one, warnings of a ‘loneliness pandemic’ and a ‘social recession’ abound. These warnings signal a relatively new understanding of loneliness – one that speaks volumes about the times we live in.

Who’s afraid of loneliness?

With social isolation measures confining many of us to a company of one, warnings of a ‘loneliness pandemic’ and a ‘social recession’ abound. These warnings signal a relatively new understanding of loneliness – one that speaks volumes about the times we live in.

The real reason we’re ad free (and six other questions from our members, answered)

What do we mean by constructive journalism? Why do we have members and not subscribers? And you get it, we’re ad free. But so what? Managing editor Eliza Anyangwe and founding editor Rob Wijnberg answer the seven most frequent questions we get about The Correspondent.

The real reason we’re ad free (and six other questions from our members, answered)

What do we mean by constructive journalism? Why do we have members and not subscribers? And you get it, we’re ad free. But so what? Managing editor Eliza Anyangwe and founding editor Rob Wijnberg answer the seven most frequent questions we get about The Correspondent.