There’s a Twitter account called Faces in Things with more than half a million followers. Once in a while it posts photos of objects – security cameras, buildings, clouds, plants, cardboard boxes – that are suspiciously human-looking.

Dormer windows become eyes, a half-open zip a grumpy mouth, the handle of a thrown-away jerrycan becomes a decorative nose.

The photos dependably receive thousands of likes, sometimes tens of thousands.

I thought of Faces in Things when I read about a study conducted 10 years ago by researchers at Harvard University and the University of Chicago, which examined the relationship between loneliness and anthropomorphism (attributing human characteristics to non-humans).

Their findings: participants who were lonely – or who, in the name of science, had been made temporarily lonely – were more likely than non-lonely participants to discern human traits in clocks, battery chargers, air purifiers and cushions.

They also had a stronger belief in the existence of supernatural powers and were quicker to attribute human emotions and intentions to their pets. Lonely people, the scientists concluded, see the world differently. They see a world in which battery chargers have intentions, dogs are like people, and lifeless objects resemble human company.

They see faces in things.

Don’t let us be lonely

“Coronavirus will also cause a loneliness epidemic,” the American journalist Ezra Klein wrote on Vox.com, as social distancing began to take hold in the US. Social distancing is required to prevent infection, Abdullah Shihipar recently wrote in the New York Times , “but loneliness can make us sick.” And on the New Yorker website, Robin Wright described how “loneliness from coronavirus isolation takes its own toll”.

Outside the US, worries about increased loneliness as countries try to mitigate coronavirus through social isolation measures abound as well. In my own country, the Netherlands, the King addressed the nation in a televised speech, reminding citizens that “while we cannot end coronavirus, we can stop the loneliness virus” by looking after those especially at risk.

It seems loneliness is almost as much on our minds as Covid-19 nowadays. This makes sense. While social isolation is not the same as loneliness, it can certainly cause it. But it is also a sign of a relatively new understanding in many societies of loneliness as a specific kind of problem.

“Loneliness,” the American sociologist Robert S Weiss wrote in 1973, “is much more often commented on by songwriters than by social scientists”. To Weiss, this lack of scholarly attention signalled professional negligence: for those who experienced it, loneliness was so unpleasant, disruptive and depressing that psychiatrists, psychologists and sociologists ought to do everything they could to understand it. Weiss’s book Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation was intended to help his professional peers achieve just that.

Almost half a century later, things look very different. All over the world, sociologists, anthropologists, psychologists, geneticists and neuroscientists are studying the prevalence, causes and consequences of loneliness.

On the heels of this academic interest, a social and cultural fascination with loneliness has popped up over the past few years as well, demonstrated by the steady stream of reports, podcasts, books and films dedicated to the topic.

The collective fear of loneliness speaks volumes about the times we live in

Loneliness is nothing new, of course: God didn’t think it was a good idea to have Adam go through life alone, and we’ve never stopped talking about it since. Philosophers from Adam Smith to Hannah Arendt have thought long and hard about it, entire novels have been written on the subject, and the history of pop music is certainly in part a history of loneliness.

(Quite often I think of Sting as he repeats with equal parts rage, despair and dismay the two-word refrain to So Lonely.)

What is new, however, is the way we’ve come to think of loneliness – as a threat to public health and, as such, a problem for all of us. What’s also new is the collective fear it instils. That fear speaks volumes about the times we live in.

What is loneliness?

Loneliness is not the same as social isolation, not the same as being alone, and not the same as solitude. In contrast to those more or less objective states, loneliness is a subjective experience – it’s “the discrepancy between a person’s desired and actual social relationships”.

In contrast to solitude, which can also be experienced as pleasurable, loneliness is never pleasant: “it is gnawing rather than ennobling, a chronic distress without redeeming features,” as Weiss put it back in 1973.

Loneliness can present itself as social loneliness – missing a group you belong to – or as emotional loneliness – missing a close bond with another person.

Loneliness can be caused by circumstances external to yourself, such as moving house or the death of a partner, but you can also be emotionally or cognitively predisposed to it. There are people who lead a solitary existence and rarely feel lonely; it is also possible to have lots of friends and close family ties and still be lonely.

And this is important: although we often think of the elderly when we think of loneliness, it affects all ages – although the likelihood of feeling lonely does increase from age 75. Other “at-risk groups” include migrants, people with health problems and those with financial problems.

For almost two decades now, there’s been an evolutionary explanation for loneliness, as is true, of course, for many of our modern troubles. Humans are social animals, that theory goes, and our chances of surviving and passing on our genes are greater when we work together. When our ancestors were still wandering the savannah in small groups, being alone was perilous, so evolution equipped us with mechanisms to make us averse to lack of social contact: when you feel lonely, you try to shake it off by looking for a connection with others – and in doing so, you increase your chances of survival.

The late John T Cacioppo, a neurobiologist at the University of Chicago and one of the founders of contemporary loneliness research, compared loneliness to pain or hunger: a sign that something is wrong, and an incentive to do something about it.

Why chronic loneliness is unhealthy

Loneliness can be temporary, mild, moderate or severe. It can also be chronic. The latter is particularly bad news. It’s this severe, lasting variant that we’re talking about when we say loneliness is a threat to public health.

Because for those who are lonely too long and too severely, the condition turns from adaptive to self-destructive. That’s hard on the mind – as the British writer Olivia Laing describes in her book The Lonely City , loneliness is something that “advances ... cold as ice and clear as glass, enclosing and engulfing”.

But it’s hard on the body, too: research shows, for instance, that lonely people move less and experience lower quality sleep than non-lonely people.

Lonely people also have higher blood pressure and a more active stress-response system; their immune system functions less well, they are more likely to suffer from dementia and run a higher risk of premature death. Of course, correlation doesn’t necessarily mean causation, but that doesn’t make the findings any less depressing.

A meta-analysis published in 2015, examining 70 studies into the health effects of loneliness and social isolation concluded that loneliness is as harmful as smoking and obesity and that it should be considered a matter of public health.

And so it is: after scientists, governments, social organisations and even international consultancies have become interested in fighting loneliness. The UK famously installed a minister of “loneliness” in 2018; in the US, the former surgeon general has been warning against the “loneliness epidemic” raging through his country for a few years now; and in the Netherlands, millions of euros have been set aside to combat loneliness. Loneliness is the new smoking, the new disease of affluence, the foremost collective enemy we have to tackle together.

“Loneliness is quite the rage,” professor Theo van Tilburg of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam told me. Van Tilburg has been researching loneliness for almost four decades – and, in fact, is delighted with the increasing interest.

Van Tilburg attributes the discovery of loneliness as a policy issue to, among other things, the insights into the phenomenon piling up from research.

Finally, he said, it has been sinking in “that lonely people aren’t just a bit unhappy, they’re also less healthy. That means they make greater demands on public health services, which in turn leads to greater interest in combating and preventing it.”

Loneliness makes you lonely

Not that it’s a simple battle. Loneliness – the severe, chronic variant – tends to be self-perpetuating. That’s because lonely people see the world differently – and seeing faces in things is the least disheartening expression of this state.

Study after study shows that a person who feels lonely is also more alert to social threats, more sensitive to negative social cues, and more focused on themselves than someone who is not lonely.

It stands to reason that all these characteristics represent obstacles to establishing meaningful social contact. Long-term lonely people, according to Cacioppo, end up adopting a “defensive crouch”, readily repelling people more than attracting them, which makes them lonelier still.

Or to quote Laing again, whose book on the topic remains among the most beautiful I’ve read: “Loneliness grows around them, like mould or fur, a prophylactic that inhibits contact, no matter how badly contact is desired.”

That makes tackling loneliness a difficult task, says van Tilburg. Attempts by organisations and volunteers to tackle loneliness “primarily focus on offering opportunities for contact. But for lonely people, it’s particularly difficult to take them up.”

"Loneliness grows around you like fur, a prophylactic that inhibits contact, no matter how badly contact is desired" - Olivia Laing

I remember a music festival that was organised in the Netherlands a few summers ago. It was called Forever Young, and the organiser hoped to bring elderly people out of their isolation. And yet, the public network news reporter doing the rounds there couldn’t manage to get a lonely elderly person talking, which isn’t so surprising: someone who is genuinely lonely won’t be in any hurry to jump on a bus with people of their age group that they don’t know, singing along to golden oldies, to run around a festival venue.

“Only those who are not lonely,” Weiss wrote in 1973, “suppose that loneliness can be cured merely by ending aloneness.”

A 2011 meta-study compared four ways in which loneliness is generally tackled: creating opportunities for social contact, increasing social support, improving social skills and tackling “social cognition”.

The last method in particular targets the subjective character of loneliness and the way in which chronically lonely people interpret social situations through, for instance, cognitive behavioural therapy or a course. It’s also emerged as the most promising method.

That makes sense, of course: loneliness is an individual experience, so the approach needs to match the individual in question. Or, as the Norwegian philosopher Lars Svendsen puts it in his book A Philosophy of Loneliness: “Loneliness will inevitably strike from time to time. It is a loneliness for which you must take responsibility. For despite everything, it is your loneliness.”

Nothing to quarrel with there – but it does sound a little lonely.

For all the attention loneliness gets, is it also on the rise? Answers vary, depending on whom you ask and how long they’ve been measuring for.

In the UK, the percentage of older people experiencing chronic loneliness has remained constant for the past 70 years. There are considerably more studies into loneliness among elderly people than among the young, but among school and university students, too, as demonstrated by a recent US study, loneliness has fallen rather than risen in recent decades. And according to loneliness figures from Statistics Netherlands, the number of severely lonely people in all age groups has remained more or less constant in recent years.

If we are experiencing a loneliness epidemic, philosopher Lars Svendsen writes, then this epidemic is unfolding mainly in the media – and in our heads. It’s the attention that has grown, not necessarily the phenomenon itself.

Why we think loneliness is on the rise

That growing attention is understandable. After all, many recent social and technological developments promise connection and freedom, when in reality they throw us back upon our own resources – an uncomfortable development which in any case arouses the fear of loneliness.

The performance society demands that everyone prioritises their own career while leaving a trail of burnt out, exhausted, depressed couch potatoes – all lonely souls who can no longer join in with the rest. And what used to be solid welfare states are now sending the message that people should look to themselves and those directly around them for help before turning to the state.

Many technological developments promise connection with others, only to throw us back upon our own resources

Social media, meanwhile, may connect us more than ever, but at the same time it makes it much easier to withdraw into our own cocoons – Alone Together, as MIT professor Sherry Turkle titled her widely read book a few years ago .

We follow, like and retweet Faces in Things, but meanwhile fear we’re forgetting how to have face-to-face contact with neighbours, checkout operators and even friends. And people who use social media a lot are at risk of comparing themselves only with the purely positive and social images others have posted, and feel even lonelier.

In fact, research into the association between loneliness and use of social media is still scarce, and what there is presents a nuanced picture: people with a good offline social network appear to do better with social media, whereas those who were already lonely do not.

It doesn’t matter: no one who has ever spent a Saturday night alone on Facebook, trawling the enviable social lives of others, will deny the feeling that this association exists.

The shared war on loneliness

Seen in this light, the fear of loneliness may be a reflection of a greater fear – fear of the consequences of perpetual individualisation, of a techno-capitalist logic that presents each of us with our own, individual reality. Fear that all that connects us melts into air, with bubbles rising to isolate us from one another even more.

You might call it cultural pessimism: fear of loneliness is fear of who we threaten to become, or perhaps already are. This means the “war on loneliness” we’ve declared so fanatically is at the same time a battle for a different kind of society.

“Together against loneliness.” That’s the tagline of the Dutch “Week Against Loneliness”. Those first two words – “together against” – are probably just as significant as “loneliness”: after all, there are few things as effective at promoting bonding as a common enemy, few things as good for a sense of belonging as collective action.

We fear vaporising everything that connects us, with bubbles rising to isolate us from one another

Moreover, the elimination of (severe, chronic) loneliness is something no one in their right mind could be against. In contrast to smoking, for instance, or not exercising enough, it has nothing to do with freedom of choice or an alternative lifestyle.

Loneliness is the flag behind which society can unite, the threat from which we flee like a herd in panic.

I once studied with an American sociologist who had, in his youth, played a pioneering role in the student protest movement. We talked about the Occupy movement , and the often-heard accusation that the movement had been ineffectual.

Not true, he said: for the people who participated, who threw their bodies into the fight, slept in the cold, went on protest marches, it had achieved everything. They had experienced what it means, along with thousands of others, to connect with something – something greater than yourself.

As we rally against the loneliness epidemic that threatens to come on the heels of the coronavirus pandemic, we do the same. However socially isolated we may be, we still reach out to one another and find ourselves in a community of goodwill.

Perhaps loneliness – not the experience of loneliness, but loneliness as a symbol – brings us together. Trembling in fear of the monster we call loneliness, we huddle together – ending up precisely where we wanted to be.

This article first appeared on De Correspondent. It was translated from the Dutch by Anna Asbury. With thanks to Annette Spithoven.

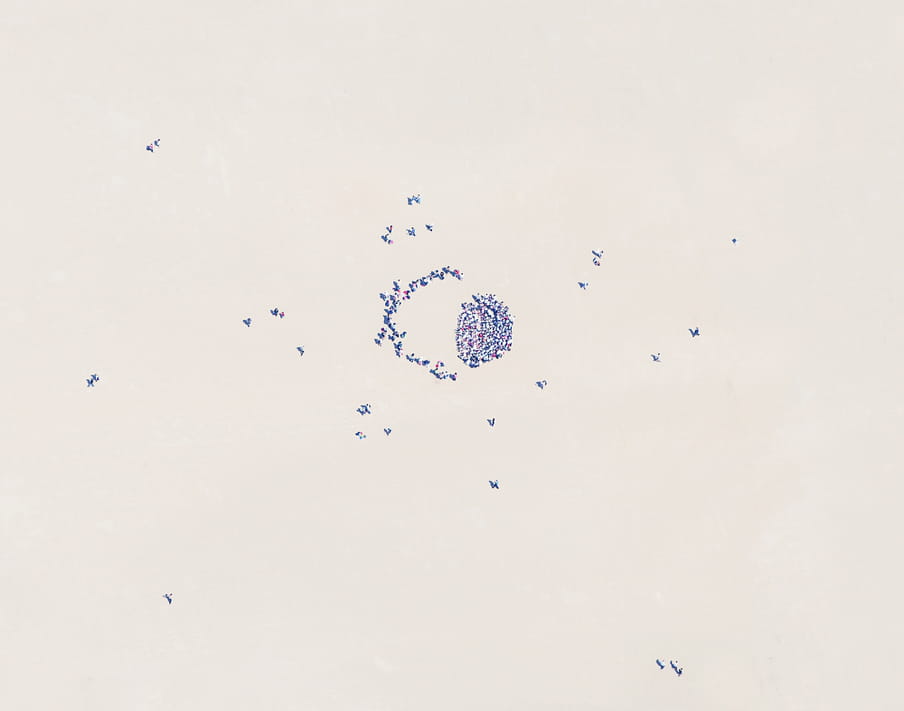

About the images

Unified Field, this series by photographer David Vintiner, shows groups of people as clusters - a formation that most of us haven’t seen for a while now. The title of the series comes from field theory in physics: "Forces can be described by fields that mediate interactions between separate objects," explains Vintiner. His images are a few years old, but in recent weeks their meaning has evolved. Vintiner shows people as pack animals, huddled together even in scenes where there is ample space to spread out. Together, each of us forms part of something bigger than ourselves. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

Unified Field, this series by photographer David Vintiner, shows groups of people as clusters - a formation that most of us haven’t seen for a while now. The title of the series comes from field theory in physics: "Forces can be described by fields that mediate interactions between separate objects," explains Vintiner. His images are a few years old, but in recent weeks their meaning has evolved. Vintiner shows people as pack animals, huddled together even in scenes where there is ample space to spread out. Together, each of us forms part of something bigger than ourselves. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Dig deeper

How we turned into batteries (and the economy forces us to recharge)

Energy has become modern society’s holy grail, but what if we don’t want to spend our limited time on Earth constantly recharging and draining ourselves? In an age of punishing pressure to be productive, saying no is the opposite of negative.

How we turned into batteries (and the economy forces us to recharge)

Energy has become modern society’s holy grail, but what if we don’t want to spend our limited time on Earth constantly recharging and draining ourselves? In an age of punishing pressure to be productive, saying no is the opposite of negative.