Could it be that when it comes to identifying what shapes our societies – either into ones that are inclusive and work for the many, or are extractive and work for the few – that rather than imagine some moral battle between good and evil, or fixate on rooting out the “few bad apples”, we should ask instead: “What incentive structures could explain what we’re seeing?”

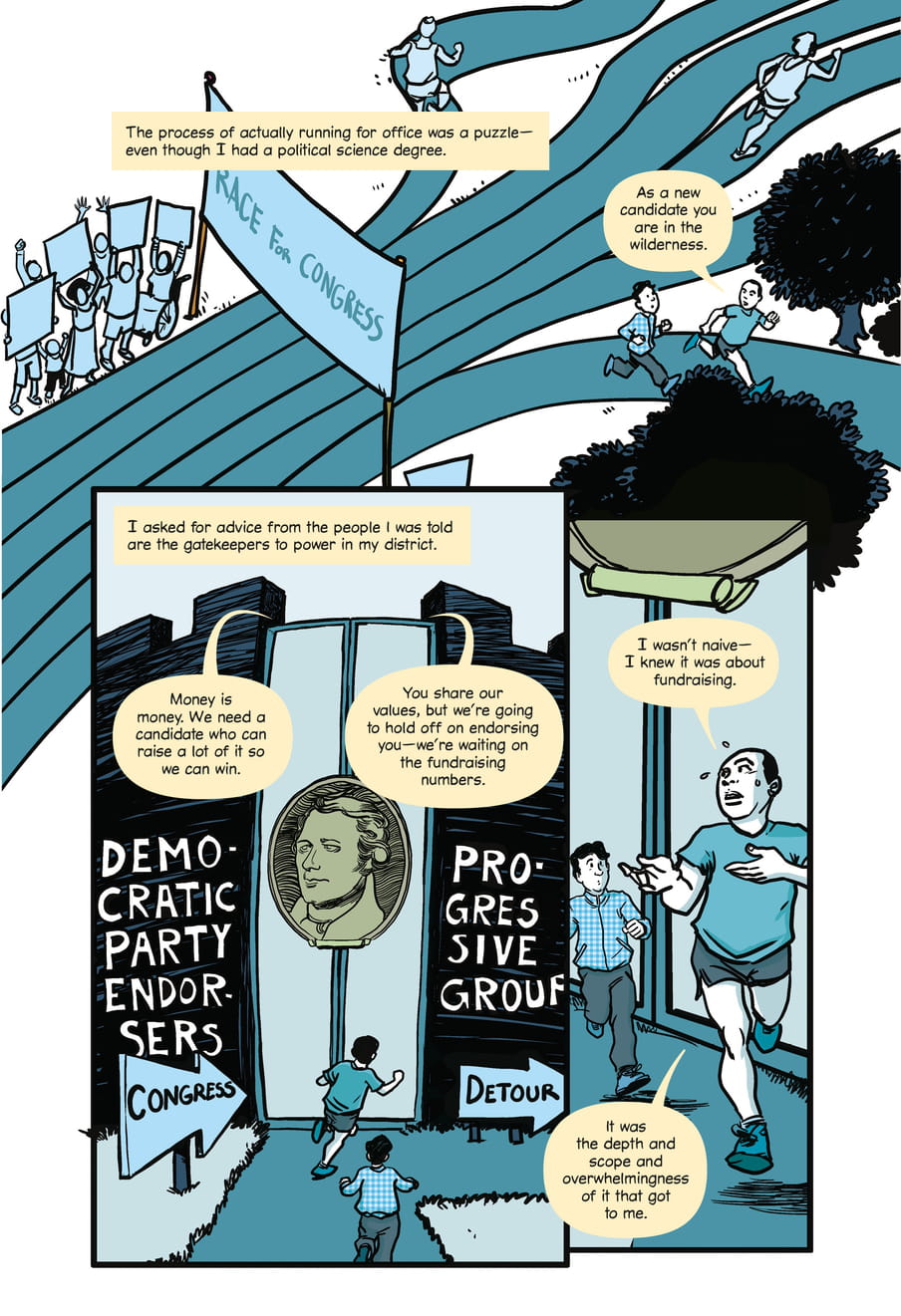

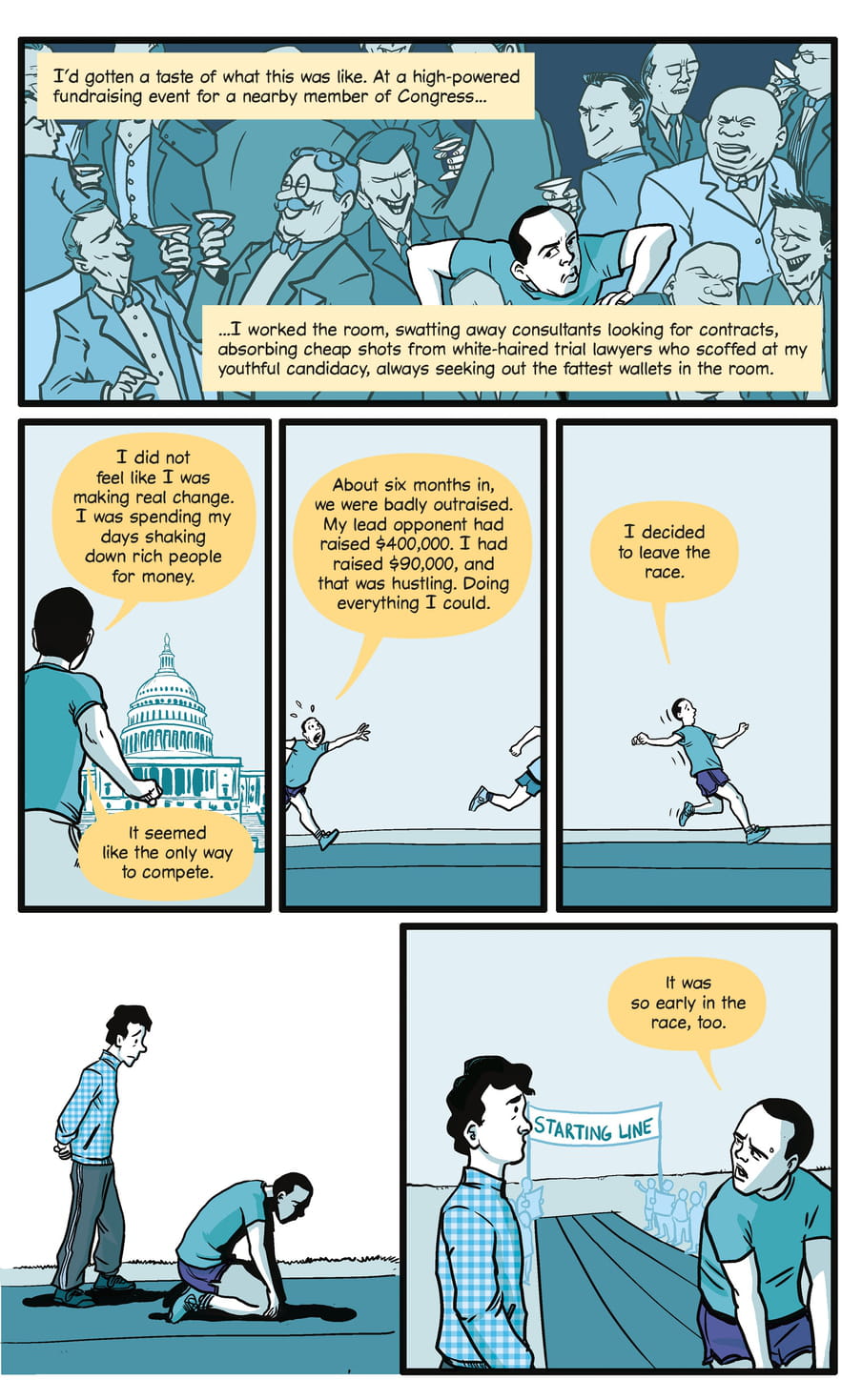

Here’s an example: in the United States, as Zaid Jilani reports, “almost US$6.5bn was spent on presidential and congressional campaigns during the 2016 US elections”. The considerable amounts of money that are required to run successfully for any type of office incentivises those in the race to focus their energies on fundraising and not actually constituency-building. If democracy is government by the people for the people, then here we see democracy working in the interests of the smallest group of people.

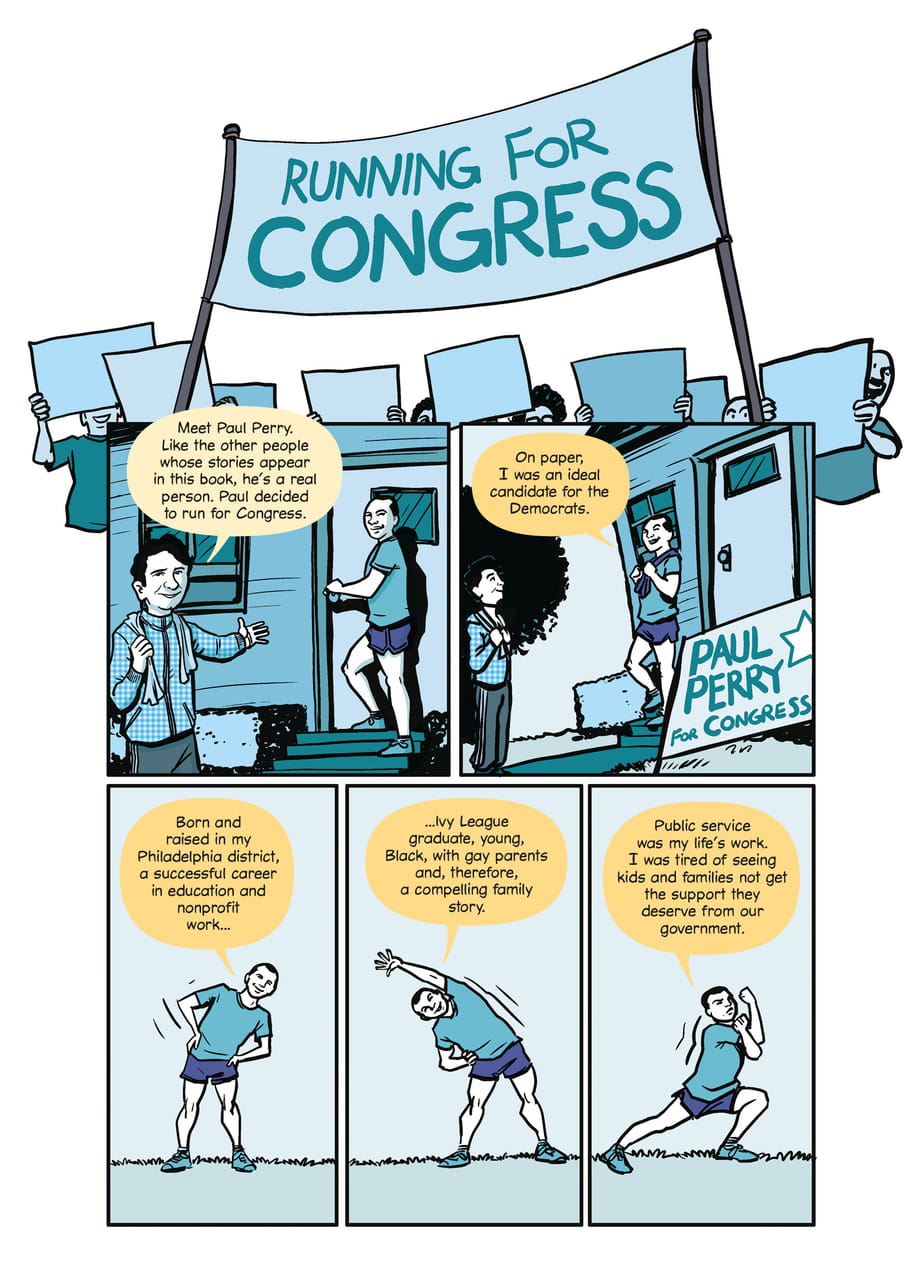

As Jilani writes of 2016: “The amount of money at their disposal enabled [some to be] competitive candidates, while others were forced to drop out not for the lack of ambition or vision but for lack of funds.”

We’re publishing below an excerpt from Unrig: How To Fix Our Broken Democracy, a non-fiction graphic novel by Daniel G Newman, illustrated by George O’Connor. It’s a first-hand account from former US congressional candidate Paul Perry, whom Newman introduces in the first panel. Perry’s experience exemplifies the latter group Jilani describes.

In Unrig, Newman attempts to show, in his own words, that “although it requires many changes so that ‘the people’ control democracy, the single most important change is to have elections financed by the public instead of wealthy corporations and special interests".

He adds: "Think of the government as an amazing, expensive sports car that we, the people, pay for through our taxes. Yet we let corporate lobbyists and billionaires pay for the key to that car – the political campaigns – which gives lobbyists control over our government. With the public paying for political campaigns, we keep the key, and the public drives the car instead of the lobbyists."

Both the illustrated story below and Jilani’s story reiterate how much of a problem the outsized influence of wealth is for our democracies – using the US as an example. But both go further to also consider what the solutions could be, drawing attention, for example, to Seattle’s democracy voucher experiment. Newman says: “In Seattle, Connecticut, and more than a dozen other cities and states with clean elections systems, candidates can run for office and win without dependence on special-interest money. By breaking the dependence between wealth and political power, we can elect the best leaders, instead of the best fundraisers.”

Read both stories together to get a fuller picture of both the problem and the solution.

– Eliza Anyangwe, managing editor

Read this story next

US elections are bought. And the people paying don’t want the same things we do.

Read this story next

US elections are bought. And the people paying don’t want the same things we do.

On your phone? Flip your screen sidewise for a better viewing experience!

More from our billionaires series

We can’t have billionaires and stop climate change

Ecological breakdown isn’t being caused by everyone equally. If we are going to survive the 21st century, we need to distribute income and wealth more fairly.

We can’t have billionaires and stop climate change

Ecological breakdown isn’t being caused by everyone equally. If we are going to survive the 21st century, we need to distribute income and wealth more fairly.

There’s no such thing as a self-made billionaire

For all their talent or intelligence, a person stranded on a desert island with no technology, infrastructure or labour wouldn’t be able to amass extreme wealth. Understanding that no one can claim that they fully deserve what they earn is the first step to addressing wealth inequality.

There’s no such thing as a self-made billionaire

For all their talent or intelligence, a person stranded on a desert island with no technology, infrastructure or labour wouldn’t be able to amass extreme wealth. Understanding that no one can claim that they fully deserve what they earn is the first step to addressing wealth inequality.