They just have time for a group photo outside the doors of the courtroom. There’s the academic who’s just taken off his cap. The human rights lawyer with the pocket square and the ponytail. The journalist in sneakers. The two men in robes. The woman from the trade union. The celebrity.

Here in this courthouse in The Hague, the Netherlands, they’ll soon hear whether they’ve managed to consign SyRI, or System Risk Indication, to history. They have serious objections to this government system that analyses all kinds of data to determine if people are committing welfare fraud. They argue that it’s not just objectionable – it’s also a threat to our human rights.

Read this story in one minute.

The SyRI case is unique because it’s one of the first times the use of digital technologies by welfare authorities was questioned on human rights grounds. And it could create a precedent as the digital welfare state advances around the world.

When the group gets into the courtroom, their faces are tense as they stand while the judge enters with two fellow judges and a clerk. There are a lot of people here, but not as many as during the hearing at the end of October, when there was an extensive debate between the state attorney and the plaintiffs. Back then, they had to set up an extra room with live video.

Today, 5 February 2020, only the judge will speak. She will not read out the decision, she says, but will instead explain the highlights from the court’s verdict in everyday language. She then explains what SyRI is.

Someone’s iPhone goes off as Siri springs to action.

The judge continues unfazed. This case is about protecting privacy. The court’s task is to assess whether the right to privacy is sufficiently guaranteed.

But "first, a point of order about the case". The court discusses the presence of Maxim Februari and Tommy Wieringa, well-known Dutch writers who joined as plaintiffs to support the lawsuit. There is nothing to suggest a direct link between their private lives and SyRI. According to the judge, the fact that this system could target "anyone", as the plaintiffs claim, is not enough. Februari and Wieringa’s participation is declared inadmissible.

It’s the first setback for this eclectic bunch of people.

Strategic litigation

The SyRI lawsuit is an example of "strategic litigation", which means that there’s more to it than just the case itself: it’s about legal, political or social change. If you dig deeper, you’ll come across all sorts of other terms – test cases, impact litigation, radical lawyering. These differ slightly in focus, but the common thread is changing the system.

So it’s not the same as taking your neighbour to court because their fence is in your garden. In that situation, your only aim is to be proven right – not to change the civil code, expose the way in which permits are granted, or question the practice of building fences in the first place.

The build up to the SyRi lawsuit shows which four steps you can take to win in court – and change the world a little while you’re at it

Strategic litigation became popular in the United States in the 20th century. In 1954, in the landmark Brown v the Board of Education case, the US Supreme Court ruled that the segregation of schools was unconstitutional. And in 1973, Roe v Wade was an important step towards the legalisation of abortion.

In the Netherlands, strategic litigation took off later. It wasn’t until 1994 that societies and foundations were allowed to undertake "collective action", making it a lot easier to start legal proceedings in support of the common good.

Since then, there have been a number of important breakthroughs. Take the climate case by Urgenda, a foundation that fights for sustainability. Together with 900 fellow plaintiffs, they argued that the state was not doing enough to prevent climate change and should change its policies. Urgenda won the case. Last December, even the Dutch supreme court agreed with the plaintiffs. It became the first major climate suit against a state ever to be won on the basis of human rights. Inadequate climate policy was judged to be a violation of those rights.

But strategic litigation doesn’t always fight for progressive causes. In the US, Abigail Fisher sued the University of Texas, claiming her application was rejected because she was white. She denounced the university’s affirmative action admissions policy, which prioritises certain minorities. The case went as far as the US Supreme Court. Fisher lost in 2016, but only narrowly: four judges were in favour of the university’s rejection of Fisher, and three against.

What makes or breaks such strategic litigation cases? The build-up to the SyRi lawsuit demonstrates four clear steps you can take to win in court – and change the world a little while you’re at it.

Step one: find a cause

Back in 2014, Tijmen Wisman – the man who would be standing in the courtroom before the judge six years later – would get together once a month with a group of people and organisations who were just as worried about privacy as he was. He was working on a PhD at the law faculty at VU Amsterdam and had been chair of the Platform for the Protection of Civil Rights (PPCR).

In the stately premises of the Dutch Humanist League, which was one of the platform’s members, the PPCR often talked about SyRI, a system that aroused everyone’s anger. The idea for SyRI came from the minister of social affairs, Lodewijk Asscher, who, ironically, used to be a leading privacy researcher. The idea was to combine all sorts of Dutch data sources – from municipalities, the employee insurance agency, the social insurance bank, and the tax and customs administration – to detect social welfare fraud.

When it came time to voting on the system, the Dutch parliament building was nearly empty. Despite critical advice from both the council of state and the Dutch data protection authority, the proposal was passed. An unbelievable result in the eyes of the PPCR. In their opinion, SyRI was a multi-headed privacy monster that could potentially affect everyone.

Their first objection: it’s almost impossible to think of any personal data that can’t be used – from information about your taxes to your work to your housing. And the government deliberately keeps secret how this data is linked together, justifying this by saying citizens could try to manipulate the system.

For the PPCR’s members, the bottom line was that "fraud" is misused as an argument in all kinds of privacy violations. The government’s tendency to spy on people had been a topic of conversation at their monthly meetings for quite some time. Take Waterproof, for instance, a project that investigated the water use of 35,000 citizens to detect fraud. With a system like SyRI, such initiatives would be established as legal.

‘Fraud’ is misused as an argument in all kinds of privacy violations

The government is becoming more and more powerful, but there is no extra protection for citizens. According to Wisman, it’s like facing off against a laser cannon with a wooden shield.

Even so, at the time of the parliamentary vote, SyRI was barely mentioned in the media. But when the law officially came into force in 2014, there were a few more murmurings. On 7 October, author Februari wrote: " Totalitarianism is spreading across the country without as much as one politician batting an eyelid."

Meanwhile, Jelle Klaas – the human rights lawyer who would pose for the group photo in 2020 wearing a pocket square – was looking for interesting strategic litigation cases. Klaas’s shoulder-length hair and earring betray his activist background. As a student, he joined protest marches against the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and later, as a lawyer, he worked on cases such as the right to food and shelter for undocumented migrants and the exclusion of students with Iranian heritage from higher education.

The right to privacy is a human right, so Klaas also visited one of the PPCR’s monthly meetings. After all, they were aware of all the sore spots for everything related to privacy. When Wisman and his associates first told him about SyRI, Klaas had no idea what it was. But the more Klaas found out, the more he realised that the PPCR had a point. SyRI did, indeed, seem to be a human rights violation.

But that didn’t mean there should be a lawsuit. Strategic litigation only works if the courtroom is the best place to tackle the problem. You could also consider lobbying, going to the media, protesting. But with SyRI? Easy. The law had already been passed. It was too late for lobbying or putting pressure on politicians.

This case could also create a precedent, which would help change the system – the ultimate aim of strategic litigation. The violation of privacy, the use of new technologies such as risk profiling, the fraud argument allowing the government to do whatever it wanted – it seemed like the perfect case to publicly expose these issues.

So it was clear: to take down SyRI, they would have to go to court.

Step two: find fellow plaintiffs

In a strategic litigation case, every step should be taken as strategically as possible. That includes getting the right people together.

But not everyone can simply go to court. If you want to go to court as an organisation, you have to be affected by the issue yourself – like when Amnesty was under surveillance in the UK – or when statutes say that you fight for public interest, or the interests of a specific group of supporters.

Of the clubs that had joined the PPCR, a few met these conditions. Privacy First fights for privacy protection for all Dutch citizens. The KDVP foundation fights for one specific group: mental healthcare patients. According to the foundation, that group could be more affected than others because SyRI might also use medical data.

And then it occurred to the PPCR: what if they could get Dutch celebrities to join the cause? A lawsuit is interesting in itself, but it would be even more exciting if famous people were involved. So they started searching.

After his critical column, Februari was a no-brainer. For him, the problem with SyRI was not so much privacy. "In 1989, I never heard anyone say that the citizens of East Germany revolted because they had so little privacy," he wrote at the time. He believed that what was really at stake here was upholding the rule of law: the judge will never have insight into the way the law is executed. That’s why, after meeting Wisman at a cafe in Amsterdam, he was happy to join the initiative.

A lawsuit is interesting in itself, but it would be even more exciting if famous people were involved

Wisman, who’s not only a privacy researcher but also a rapper, remembered that writer Wieringa was on the jury during his very first battle. Wieringa’s name had already been mentioned several times at the PPCR’s meetings because he had been fiercely critical of the government’s approach to fraud prevention in a public lecture. "The state isn’t acting as it ought to [...]. With the inevitability of a natural law and the nerve of a gangster, it continually transgresses the boundaries of personal privacy, a domain that keeps shrinking and shrinking."

Wieringa himself had been playing with the idea of a lawsuit. He had even asked his wife – a human rights lawyer – if she would be interested in taking the government to court together over SyRI. But she thought a prosecuting couple was a bad idea. And too expensive. But when Wisman asked him to join the coalition, Wieringa didn’t have to think twice.

At the end of March 2018, after the summons had already been served, Kitty Jong heard about the case. She is the deputy chairman of the federation of Dutch trade unions (FNV) and was becoming increasingly worried about the culture of distrust in the Netherlands. She had noticed that people who receive money from the state are given a very hard time. And the rules pertaining to the weakest members of society also happen to be the most complicated ones. She clearly remembered a meeting she had with some people who were on welfare, who showed her the forms they had to complete. Even she, a union administrator with a university degree, could not make sense of them.

So she too needed little convincing when her colleague at the trade union told her about the SyRI lawsuit. She realised that when it comes to social security, there’s not much point in going on strike. It’s better to go to court. So she got in touch with the coalition and asked if she could join the plaintiffs. Klaas thought this was good news. It would give the case broader appeal if it wasn’t only backed by human rights enthusiasts and privacy devotees.

And so they went to court to ask if the FNV could join as a plaintiff. On 26 September 2018, it was ruled that the trade union was in.

Step three: set up a publicity campaign

"I think the government is actually behaving very badly," Wieringa said as a guest in a talk show in January 2018. He said he felt like the walls of his house were made of glass. "I feel watched."

When the host wanted to ask a follow-up question, she was interrupted by Charles Groenhuijsen, who was on the show to look back on US President Donald Trump’s first year in office. "But what if the system helps you find an ecstasy lab or a marijuana farm?"

It’s "despicable", Wieringa replied, to comb through a whole city or neighbourhood just to find that. "You claim you have nothing to hide," Wieringa continued. "But you must have had moments in your life when you did have something to hide. Your last STD test, for instance, when was that? And what were the results?"

The goal of strategic litigation is often more than just to be proven right by the judge. It’s also about raising awareness. Urgenda’s climate lawsuit helped make people more aware of climate change. The cases in the US during segregation galvanised debates about racism.

In the case of SyRI, the plaintiffs realised that raising awareness would actually be quite difficult. The system is shocking, but also abstract. That’s when it can be helpful to have some celebrities on hand to explain it. Like when Wieringa brought up the STD test.

The goal of strategic litigation is often more than just to be proven right by the judge. It’s also about raising awareness

The coalition against SyRI slowly set up a big publicity campaign. They joked to one another that the goal was to be able to explain the problem with SyRI to your mother-in-law, starting with a catchy title for the campaign: Suspect until Proven Otherwise.

Ronald Huissen was the linchpin of the campaign. He’s the PPCR’s secretary and their in-house journalist, the one wearing sneakers in the court photo. He wrote countless articles for the Suspect until Proven Otherwise website, got in touch with other media, and set up campaigns to get the word out about SyRI.

The most important campaign Huissen worked on was with the FNV, which set its sights on two disadvantaged neighbourhoods in the city of Rotterdam, where an above-average number of people are on welfare. Some might call them "bad" neighbourhoods.

These were neighbourhoods in which the government had used SyRI to look at 12,000 addresses, after which the Orwellian-sounding "Intelligence Bureau" used an algorithm to identify 1,263 suspicious addresses.

The FNV wanted to put a stop to this, and Huissen helped them with the thorough knowledge of the case he had built up by then. On 19 June, they organised a meeting with about 80 residents, the majority of whom were of Moroccan descent.

One of the residents asked whether this was discrimination. "If you only select certain neighbourhoods, you’re discriminating,” Wisman answered. "Not necessarily in terms of race, but class."

On 27 June, a group of residents gave Rotterdam mayor Ahmed Aboutaleb a book about nepotism and corruption in the Netherlands to show that real fraud can be found elsewhere, namely in politics and business. Among the rich, not those living in poverty.

Aboutaleb seemed to get the message. In a city council meeting on 2 July, wearing his chain of office, he called SyRI “a Moloch of bureaucracy”, before pulling the plug on the project in Rotterdam.

Step four: use any legal means available

Earlier, in October 2018, Klaas had travelled to Belgrade for a retreat organised by the Digital Freedom Fund, which supports strategic litigation in the field of digital rights. There he met Christiaan van Veen, who works with Philip Alston – the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights – and gave a presentation about their research on "digital welfare states".

During a recent trip through the US, Alston and van Veen had noticed how social welfare is increasingly being farmed out to databases and algorithms. Like – and this is a mouthful – the Vulnerability Index-Service Priority Decision Assistance Tool (VI-SPDAT), which is used in Los Angeles to rank homeless people in terms of vulnerability and assign them housing.

Van Veen realised SyRI was another example of this trend. He discussed an idea with Klaas: shouldn’t Alston assist the case by writing to the courthouse in The Hague? In the Netherlands, such an "amicus curiae" is not customary, but it’s not illegal either. That too was strategic: using every legal tool, including unconventional means. It could mean that the judges would be reminded again of what was at stake.

And it was quite a logical choice for the UN Human Rights Rapporteur to get involved in the SyRI case. Because at its heart, it is about human rights. The Dutch often think of other countries when that subject comes up. When Klaas once wrote to Dutch political parties to talk about human rights, he was almost exclusively set up with MPs with foreign affairs portfolios. But human rights are violated in the Netherlands too. It was not for nothing that Urgenda successfully appealed on the grounds of human rights.

The argumentation had to be airtight. The plaintiffs weren’t interested in winning only for SyRI to be used again with a few small modifications

In the end, Alston wrote a brief in September 2019 with help from Van Veen, who had meanwhile started leading a research project on the digital welfare state at New York University. The brief didn’t mince words: SyRI and other similar systems "pose significant potential threats to human rights, in particular for the poorest in society". Alston discussed it on national television, followed by images of Rotterdammers barbecuing as they celebrated the mayor shutting down SyRI.

But ultimately, of course, it all comes down to what happens in the courtroom. The argumentation had to be airtight. The plaintiffs weren’t interested in winning only for SyRI to be used again with a few small modifications. Four members of PPCR endlessly sifted through documentation. (Wisman, who also had to finish his PhD thesis, put in many late nights.) They emailed Word documents back and forth to the lawyers.

Ultimately, the lawyers appealed to human rights in the courtroom – the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) to be precise.

In the Netherlands, the judge cannot argue against the constitution, so you have to go for an international angle straight away. That’s a good thing because it means the verdict could also influence other countries.

And speaking of strategic, the coalition carried out each of these steps as strategically as possible: they looked for a fitting and mediagenic goal, found interesting fellow plaintiffs, came up with clever tactics to get publicity, and meticulously prepared for the legal battle. All tricks that had worked for other cases, both in the Netherlands and elsewhere.

But would it be enough in the SyRI case?

5 February 2020

Klaas, Wisman, Jong, Februari, Huissen – they’re all awaiting the verdict with bated breath. Only Wieringa, who’s travelling, is missing.

The judge continues: social security is very important for Dutch society. "Fraud erodes the solidarity on which this system is founded." This means good monitoring is important, and so SyRI serves a "legitimate purpose".

Will the judge declare the system legal after all?

The sun shines through the windows of the courthouse. The judge carries on: "The development of new technology, however, also means that the right to the protection of personal details gains new meaning."

If this wasn’t a lawsuit, someone would start clapping now

And those two things – that legitimate goal and breach of privacy – must be weighed against each other. The state believes that they are balanced. The attorney has argued that there are sufficient safeguards to protect privacy, and that the system is only used when necessary.

"The court cannot test the veracity of the state’s position on what SyRI is exactly." It isn’t clear what the risk model is, the judge argues, or which data are used.

If this wasn’t a lawsuit, someone would start clapping now.

Now things move quickly. The judge does not feel that the "fair balance" requirement has been met. She expresses her concern about the "bias" in the system. And she adds that "it’s practically impossible to imagine any personal data that can’t be used by SyRI".

Ultimately, the system violates article 8, paragraph 2 of the ECHR. In plain English: SyRI is in violation of human rights laws. The judge calls a halt to the system.

The disparate group slowly trickles out of the courtroom, their expressions ranging from elated to dazed. The judge has agreed with them on almost every point. Sitting on benches in a corner of the courthouse, looking out over The Hague, they congratulate one another. Now and then, a journalist comes up to them looking for a quote. They say to each other that declaring a law unconstitutional is not something judges do every day.

But apparently SyRI isn’t just any case.

Translated from the Dutch by Hannah Kousbroek.

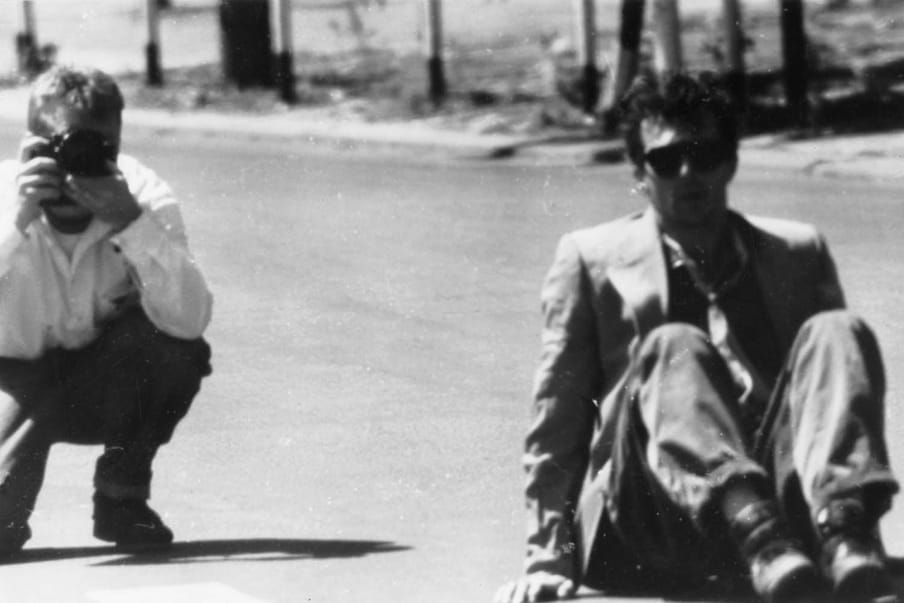

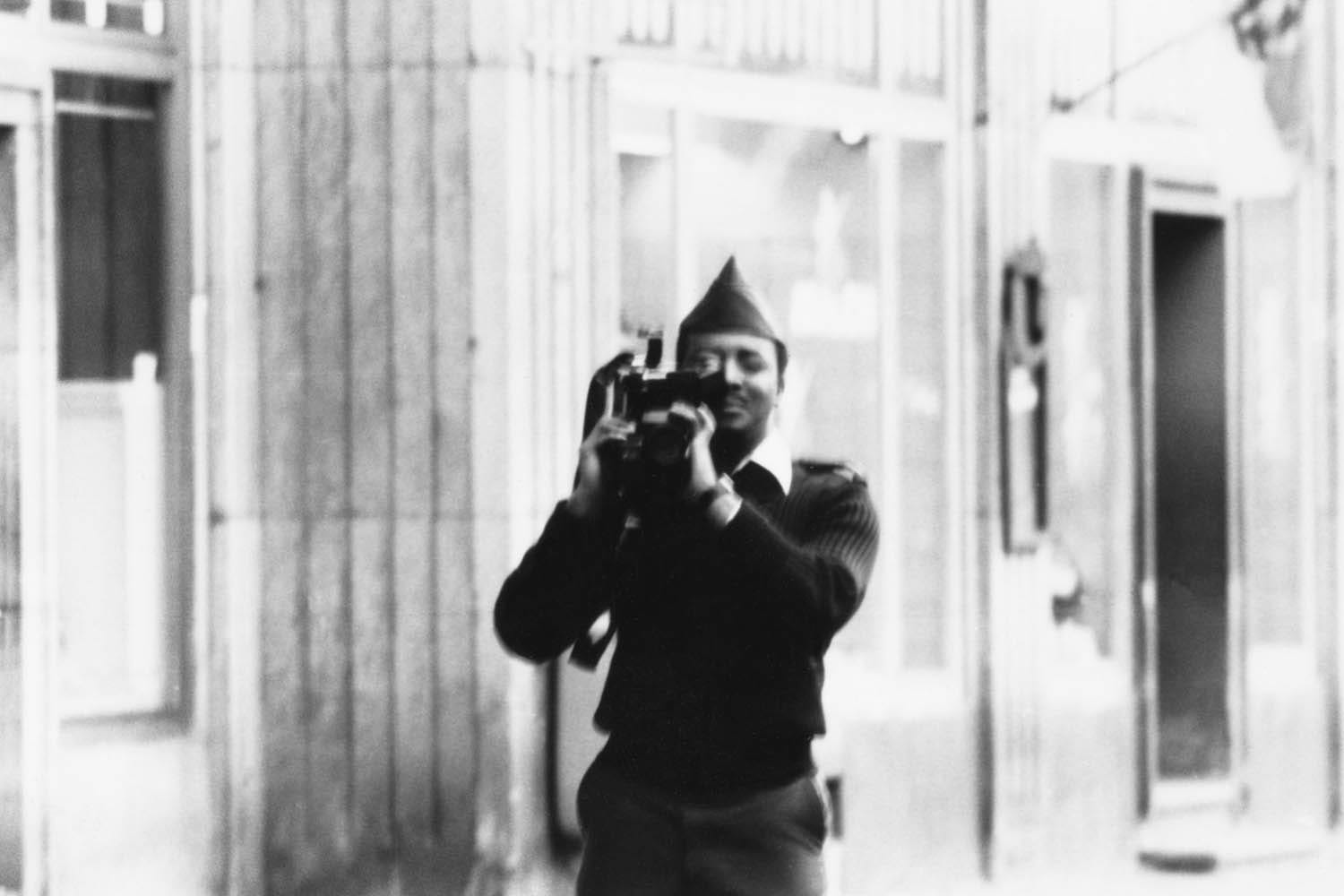

About the images

German artist Simon Menner researched the image archive of the German Democratic Republic’s ministry for state security (Stasi), one of the most effective surveillance apparatuses in history. He made collections of the types of images that he saw recurring. One of those collections, Spies Photograph Spies, is published with this article. During his detailed research into the subject of surveillance, Menner came to realise that the public has only very limited access to picture material showing the act of surveillance from the perspective of the surveillant. "We are naturally all familiar with the blurred images taken by surveillance cameras and occasionally released to the media, for example in conjunction with police investigations. Yet there is still a large grey area, which is often spoken about but of which little is tangible. It is obvious that much more surveillance material must exist; what is not obvious, however, is what the Orwellian ‘Big Brother’ in fact gets to see when he is watching us." (Isabelle van Hemert, image editor)

About the images

German artist Simon Menner researched the image archive of the German Democratic Republic’s ministry for state security (Stasi), one of the most effective surveillance apparatuses in history. He made collections of the types of images that he saw recurring. One of those collections, Spies Photograph Spies, is published with this article. During his detailed research into the subject of surveillance, Menner came to realise that the public has only very limited access to picture material showing the act of surveillance from the perspective of the surveillant. "We are naturally all familiar with the blurred images taken by surveillance cameras and occasionally released to the media, for example in conjunction with police investigations. Yet there is still a large grey area, which is often spoken about but of which little is tangible. It is obvious that much more surveillance material must exist; what is not obvious, however, is what the Orwellian ‘Big Brother’ in fact gets to see when he is watching us." (Isabelle van Hemert, image editor)

Dig deeper

An algorithm was taken to court – and it lost (which is great news for the welfare state)

As governments and big tech team up to target poorer citizens, we risk stumbling zombie-like into an AI welfare dystopia. But a landmark case ruled that using people’s personal data without consent violates their human rights.

An algorithm was taken to court – and it lost (which is great news for the welfare state)

As governments and big tech team up to target poorer citizens, we risk stumbling zombie-like into an AI welfare dystopia. But a landmark case ruled that using people’s personal data without consent violates their human rights.