For the Bahamas, the climate apocalypse came on 1 September 2019.

For roughly 24 hours, Hurricane Dorian inflicted the peak of its 300 km/h winds on Abaco and Grand Bahama Islands, raising the level of the ocean by seven metres, washing entire towns into the sea, and levelling even concrete storm shelters. It was perhaps the worst 24-hour period of weather in a single place in the recorded history of the western hemisphere.

One month later, more than 1,000 people are still missing and 70,000 are homeless – in a country of 400,000. The storm also inflicted a severe economic shock: 58% of the country’s GDP was lost overnight. Prime Minister Hubert Minnis called it “the greatest national crisis in our country’s history”.

There were centuries of decisions embedded in those winds and waves

But even these bleak facts fail to convey what it must have been like for the people hunkered down that dreadful day. Unearthly sounds of rending sheet metal and splintering wood, the rain and sand and ocean water pummelling every surface. Stories emerged of a man, wheelchair-bound and sitting in floodwaters for 48 hours. It is a testament to the human spirit that anyone survived at all.

As a force of nature, Dorian was beyond compare. It was the strongest hurricane to make landfall in all 150 years of documented storms in the Atlantic Ocean. But its cause was anything but natural. There were centuries of decisions embedded in those winds and waves.

In the immediate aftermath of the hurricane, headlines described the Caribbean archipelago with words such as "crippled" and "hell" and "devastation" – and then, as usual, the international media went almost entirely silent.

At time of writing, the last article on Dorian by the New York Times was written on 17 September for its travel section, urging readers to plan their next vacation to the Bahamas, as though a poolside drink and a weekend getaway were proper substitutes for a less extractive economic system.

No room for justice and regeneration

Climate change itself is simple. I can explain it in one paragraph: by a quirk of physics, fossil fuels are an almost perfect store for energy, and their discovery helped accelerate centuries of colonialism, locking us into an extractive relationship with our planet and each other. The subsequent imbalance in resources was exploited by those with economic or military power, enriching the few at the expense of the many.

Now, after decades of wilful delay, the weather itself is changing. The strongest hurricanes, like Dorian, have become even stronger, slower moving, and more destructive. Global leaders have continued to support an economic system that is accelerating these effects, though climate and ecological science has known for decades that doing so risks disturbing the delicate balance of our small planet.

Climate change is not a war, it is genocide. It is domination. It is extinction

The latest science says we have come, at last, to the brink. At this point, we need “rapid and far-reaching transitions” in “all aspects of society”. There is no time left to wait.

But the fix is not simply technical. The too-familiar apocalypse narrative leaves no room for justice or regeneration. We must do better. Somehow, we must also learn to treat each other better.

But how do we do that? Figuring out exactly the steps we must take to address this emergency, that’s hard. There are no computer models, no satellites, no radars, no hockey stick graphs that can help us chart our way toward the kind of civilisations we urgently need to build.

The too-familiar apocalypse narrative leaves no room for justice or regeneration

Surely the only way to begin is to reckon with the gravity of this moment, reconnect with our shared humanity and forge on together. In the words of US President John F Kennedy, we must do these things not because they are easy, but because they are hard. Slowing down planetary collapse is the hardest thing we may ever have to do as a species, but it is also – unequivocally – the most important.

In all of history, no other human force besides armed conflict has driven more people from their homes. No other force could destroy an entire island overnight, could make vast swaths of the world uninhabitable, or cause the graves of hundreds of centuries of ancestors to permanently sink beneath the sea.

Today, there are more than 70 million forcibly displaced people around the world. There are no reliable figures on how many of these are related to environmental degradation, disasters, and climate change, not least because climate change now deeply affects almost every human system on Earth. In our lifetimes, without a radical change, this number could increase tenfold.

Climate writers often slip into a war metaphor. But climate change is not a war, it is genocide. It is domination. It is extinction. It is the most recent manifestation of how powerful men throughout history have sought to steal from the less powerful, and dismiss them as merely inconvenient. Understanding climate change in this way transforms everything.

The emergency looks like violence

Worse than the way we talk about this moment in history is the realisation that the narrative of climate apocalypse is not a catalyst to action. Instead, it helps reinforce the business as usual trope: if we’re going to lose the Bahamas anyway, why change course?

Seen through the lens of climate inaction, against a backdrop of unfettered economic growth, one can only conclude that climate change is an intentional act, in which the media is complicit.

Just days after the storm had swept away buildings in the Bahamas, American media was curiously obsessed with President Trump’s stubborn insistence that Hurricane Dorian would hit Alabama.

The narrative of climate apocalypse is not a catalyst to action

From the descendants of slaves in the Bahamas, forced once again onto boats as they fled, to the burning homelands of indigenous peoples in the Amazon, their forests cleared for cattle ranching and soy plantations, to the Syrian refugees of a conflict in part triggered by years of drought, the climate emergency looks like violence.

There is no need to convince anyone in the Bahamas that everything is different now. As a country that has contributed a mere 0.01% to global greenhouse gas emissions yet suffers some of the worst consequences of the climate emergency, no one there needs convincing that inequality is part of the problem.

What they also know with certainty is that it will take years, decades even, for the residents of Abaco and Grand Bahama Islands to rebuild their lives from the rubble. Writing in the New Yorker, Bahamian journalist Bernard Ferguson captured this feeling when he said: “The death toll, when tallied, may never be a complete or accurate expression of the lives that the storm claimed.”

For people living on the front lines of climate change around the world, there is no physical defence against this kind of unnatural, man-made violence. “The most potent defence that we have,” added Ferguson, “is to strategise and organise collectively, across countries, to reverse our course.”

An alternative story of climate change

This is what the climate emergency looks like, not stories of solar tech and world leaders signing a lukewarm, lowest-common-denominator agreement – and definitely not a simple statement of long-established physical science.

We need to know, viscerally, that we can no longer abandon our neighbours in their time of greatest need

It is the minute-by-minute revolutions that are happening in nearly every home and neighbourhood around the world where people are simply claiming the right to exist. It is not just the contemporary image of a family standing amid their island ruins; the climate emergency looks also like the 500-year history of colonialism in the Americas. This has been happening for a long time, because climate change is a crisis of our relationship with one another and with nature.

What this moment needs, more than anything, is moral clarity, the kind demonstrated at the United Nations by a 16-year-old Swedish girl and countless other young people from around the world.

We need to know, viscerally, that we can no longer abandon our neighbours in their time of greatest need. We need to relearn our interdependence. There is the alternative. The way to write this story that doesn’t end in apocalypse.

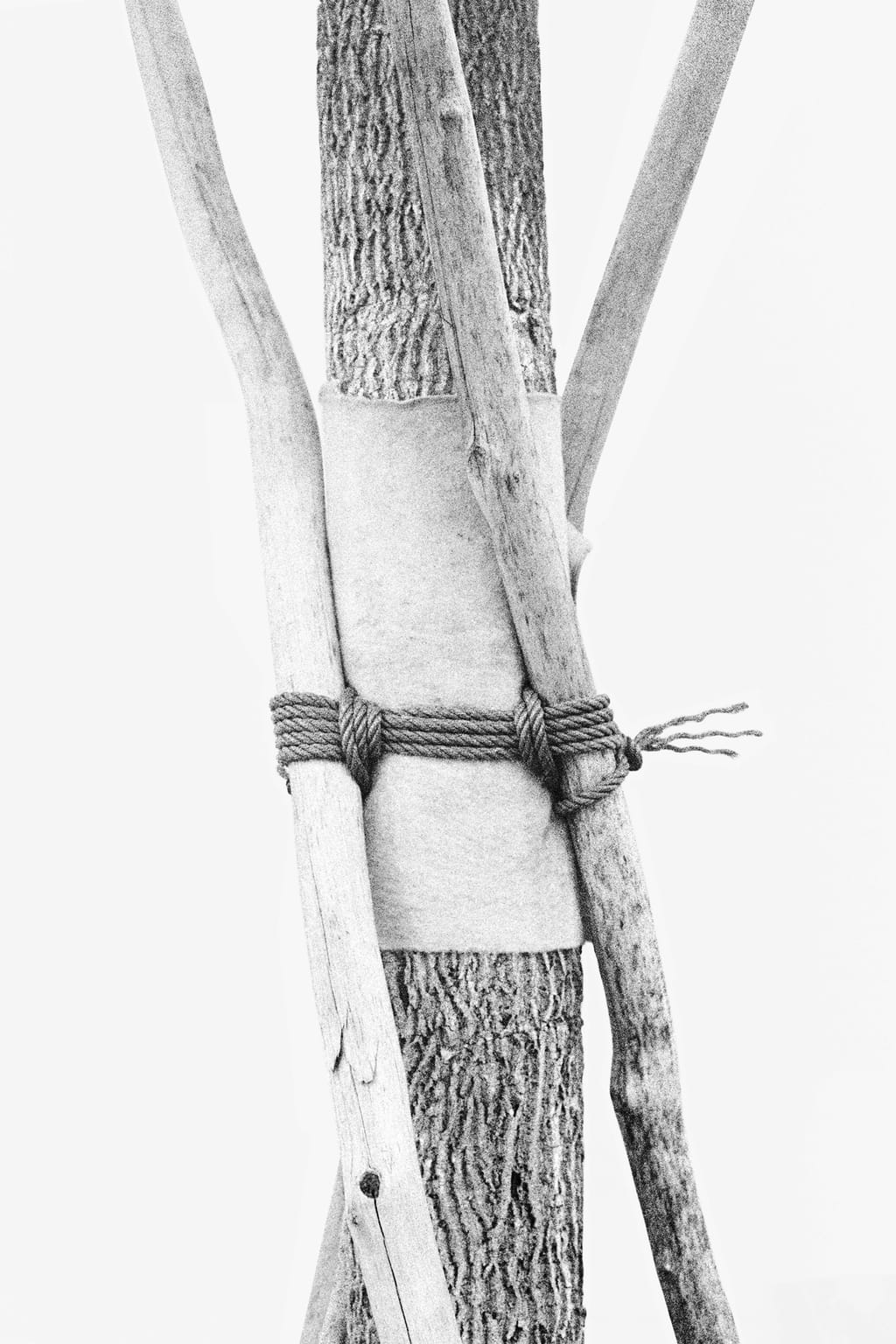

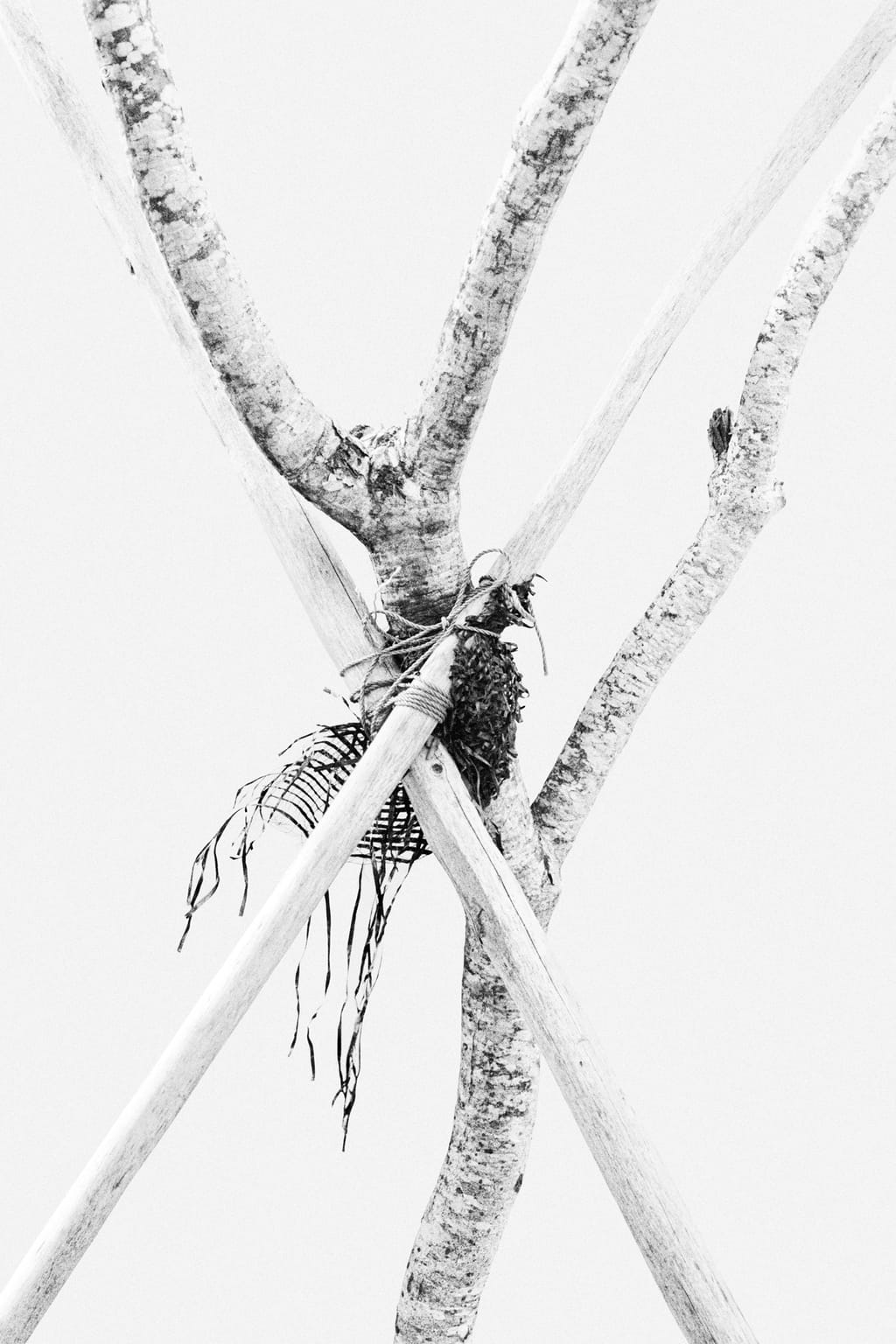

About the images

Woong Soak Teng’s work focuses on the relationship between human beings and their surroundings. In this series she created a typology of different permutations of tree staking in Singapore. As in many cities around the world, trees in Singapore are uprooted and relocated to conform to the design of a controlled cityscape. After relocation, the trees need to be guided to grow in the right direction, resulting in a wide range of personal (and sometimes unorthodox) approaches to the art of tree-tying. These intimate portraits contain a definite paradox: the urge to control our environment side by side with the personal, helpful touch of inventive tree-tying techniques. You could read these intimate portraits as a metaphor for what is needed to deal with the climate crisis: human intervention, invention, and action. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

Woong Soak Teng’s work focuses on the relationship between human beings and their surroundings. In this series she created a typology of different permutations of tree staking in Singapore. As in many cities around the world, trees in Singapore are uprooted and relocated to conform to the design of a controlled cityscape. After relocation, the trees need to be guided to grow in the right direction, resulting in a wide range of personal (and sometimes unorthodox) approaches to the art of tree-tying. These intimate portraits contain a definite paradox: the urge to control our environment side by side with the personal, helpful touch of inventive tree-tying techniques. You could read these intimate portraits as a metaphor for what is needed to deal with the climate crisis: human intervention, invention, and action. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect that the New York Times pieces referred to was not, at time of publication, the lastest article on Hurricane Dorian on the site.

Follow Eric’s work:

Join the conversation about where we go from here

Eric sends a weekly newsletter where he shares his reporting in a more personal way. Here he also shares insights from the books, articles, or podcasts he’s found throughout the week.

Join the conversation about where we go from here

Eric sends a weekly newsletter where he shares his reporting in a more personal way. Here he also shares insights from the books, articles, or podcasts he’s found throughout the week.