Let’s start by debunking something sacred: the 10,000 hour rule.

The claim that you can become an expert at anything as long as you put in 10,000 hours of training (even more is better), preferably from a young age, is largely nonsense. Investigative journalist David Epstein takes apart the theory in his book, Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialised World.

Of course, there are examples of individuals who specialised at a young age and became truly exceptional artists, athletes or scientists. Tiger Woods received a putter from his father when he was still a baby, appeared on television as a toddler, beat trained adults at the age of four, and went on to become the world’s top golfer.

But a prodigy like Woods is a mediagenic exception.

Read this story in one minute.

Far more common is the path travelled by tennis player Roger Federer. He is every bit as successful as Woods, but his sporting education is not as well known, probably because it was so boringly normal. Federer participated in all kinds of sports in his youth, preferring to keep playing with his friends instead of moving to a higher training group, and didn’t choose tennis as his sole sport until relatively late.

Epstein’s message: there’s no need for early specialisation – eventually, you’ll get all the practice you need. What’s more, you don’t even need 10,000 hours of training.

Roger is the rule – not Tiger.

Malcolm Gladwell changed his mind about the 10,000 hour rule

The science of talent development has always been nuanced. Swedish psychologist Anders Ericsson, whose work provided the foundation for the 10,000 hour rule, rejected simplified readings of his work, like the one presented in the book Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell (who later, prompted by Epstein, admitted his interpretation was flawed).

Yet dispelling nonsense is much harder than spreading nonsense. Partly because the 10,000 hour rule is such a wholesome, seemingly logical, inspiring concept. Who wouldn’t like to believe you can achieve a great deal, or even anything, through dedication and perseverance?

Not many people, as it happens. Epstein sees a worldwide cult of the head start – a fetish for precociousness. The intuitive opinion that dedicated, focused specialists are superior to doubting, daydreaming Jacks-of-all-trades is winning. Even though Roger is the rule, the world sees Tiger as the example to emulate.

The intuitive opinion that dedicated, focused specialists are superior to doubting, daydreaming Jacks-of-all-trades is winning

Sports teams are scouting for and training top talent at younger and younger ages. Training schedules are so intensive that it is becoming increasingly hard to take up a second sport.

These are astonishing sacrifices made in the quest for efficiency, specialisation and excellence. (Another example: the on-going worry about whether or not students’ degree choices are "labour market relevant".) As if teenagers could or should already know who they are and what they want to be. As if every year spent doubting and widening someone’s horizons – taking up a different sport, direction, or study – is a wasted year for the individual or society.

Epstein argues that this is not only untrue but counterproductive. Seemingly inefficient things are productive: expanding your horizons, giving yourself time, switching professions.

The Polgár method

Range might come across as a one-sided, book-length popular science sermon that could launch a long-term career as a well-paid keynote speaker. However, Epstein’s strong point is that he never loses sight of the ifs and buts in his argument.

He explains in detail that early specialisation is a good idea if you want to become successful in certain fields, sports or professions. In fact, in some cases, it’s the only option. Take chess, for example: if you don’t start early, you won’t stand a chance at glory.

László and Klara Polgár realised this some time ago. In the 60s, the Hungarian couple met and fell in love because of a shared disapproval of the traditional school system, so they decided to educate their own children to make them geniuses. The couple believed anyone could excel at anything if they were dedicated enough. Deciding which field their children were to excel in seemed less of a concern.

The Polgárs shared a disapproval of the traditional school system, so they decided to educate their own children to make them geniuses

In the end, the Polgárs chose chess. They were inspired by the 1972 match between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer, but a more important factor in their choice was that success at chess is, in Klara’s words, "very objective and easy to measure". Determining which musician is best is a matter of taste, but you can easily see who’s the best chess player by looking at the ranking. In other words, chess would clearly demonstrate whether their educational philosophy was correct. (Such dedication to science!)

In one of the book’s beautifully detailed case studies, Epstein explains that the experiment in their family laboratory was a staggering success. All three Polgár daughters became chess geniuses. Susan was the first woman to enter the men’s world championships, Judit became the youngest (male or female) chess grandmaster ever at 15, and Sofia became an International Master – still a level with an exclusive number of members.

Unsurprisingly, László was euphoric. He thought finding a cure for Aids would only be a matter of time if more people raised their children according to the Polgár method.

Friendly and hostile learning environments

But László’s logic was flawed: learning chess is not a good model for learning other things. Epstein explains this using the work of psychologist Robin Hogarth, who makes the distinction between friendly (kind) and unfriendly or hostile (wicked) learning environments.

In a friendly learning environment, such as chess, the rules are clear, the information is complete (all pieces are visible on the board), and you can (ultimately) determine the quality of every move. In other words, the feedback loop works in chess, so experience makes a player better. (This is the reason a chess app on your smartphone is almost certainly better than world chess champion Magnus Carlsen). Tennis, classical music and golf are other examples of friendly learning environments with set rules, recurring patterns and working feedback loops.

We are all experts in one comparable area. A simple experiment demonstrates this. Take 20 seconds to memorise the words below in their given order:

order the correct is

in to difficult are

the not remember

words that it.

Difficult, if not impossible. Now try to memorise the following series of words:

It is difficult

to remember words

that are not in

the correct order.

You’ll probably manage this in five seconds. So language is a friendly learning environment. After all, there are fixed rules (grammar) that you can master with practice.

However – and this is Epstein’s big point – friendly learning environments are the exception. The world is not as clear-cut as golf or chess. So early specialisation is often a bad idea.

As Epstein puts it: "When we know the rules and answers, and they don’t change over time … an argument can be made for savant-like hyper-specialised practice from day one. But those are poor models of most things humans want to learn."

Most things that people want to learn do not resemble language, golf or chess, but rather a game in which the generalist has an advantage. A hostile learning environment – or "Martian tennis".

The world is more like a game of ‘Martian tennis’ than a football match

"Martian tennis" is an expression Epstein uses to describe an activity in which the rules aren’t certain. There are balls and rackets, but apart from that, not much is certain: there are no lines marking the playing area, nobody waits their turn, the rules are unknown and constantly changing, and even the purpose of the game is not always agreed on.

In hostile learning environments without repetitive patterns, mastery is much harder to achieve. The feedback loop is insidious. Unlike chess, experience does not necessarily make you better. You may stick with the wrong approach because you’re convinced it’s the right one.

The world has more in common with jazz than classical music

Hogarth offers a wonderful example of a hostile learning environment. At the beginning of the previous century, a New York physician gained fame because he was able to diagnose typhoid in patients who didn’t display the symptoms until weeks later. Among other ways, the miracle doctor did this by touching the patients’ tongues with his fingers and "recognising" typhoid fever by its texture.

Years later, the secret of his "success" became clear. The doctor had been carrying the bacterium and was spreading it in the most effective way imaginable. And all this time, the eminent doctor was genuinely convinced that he had a gift. The feedback he received was perfectly wrong – now that’s a hostile learning environment.

In learning environments without repetitive patterns, where cause and effect are not always clear, early specialisation and spending countless hours does not guarantee success. Quite the opposite, Epstein argues. Generalists have the advantage: they have a wider range of experiences and a greater ability to associate and improvise. (The world has more in common with jazz than classical music, Epstein explains in a chapter on music.)

Why generalists do better

Many modern professions aren’t so much about applying specific solutions than they are about recognising the nature of a problem, and only then coming up with an approach. That becomes possible when you learn to see analogies with other fields, according to psychologist Dedre Gentner, who has made this subject her life’s work.

An example of analogical thinking is "Duncker’s radiation problem", a well-known problem in psychology. A cancer patient’s tumour can be removed using radiation, but excess radiation simultaneously breaks down healthy tissue. Weaker radiation saves the tissue but doesn’t effectively treat the tumour. What to do?

To most people, the solution becomes clear after hearing the analogy of a general who had to take a fortress with a platoon of soldiers. The problem was the roads to the fortress were littered with mines that would go off if all the soldiers marched along a road at the same time.

The general’s strategy? He split the platoon up into small groups, each taking a different route to the fort, so there was less weight on the road and less chance of setting off a bomb. So a solution to Duncker’s problem: several smaller rays would be required to fight the tumour, instead of one large ray.

Late specialisation explains Federer’s long career: for him, tennis is not a job but a passion

Generalists are – yes – generally better at this type of problem. Epstein further illustrates his point with the example of 17th century astronomers Kepler and Galileo, whose breakthroughs were the result of studying analogies, and the fact that Nobel Prize winners engage in far more serious pastimes than less prominent scientists, which probably makes them more wide-ranging and creative.

Another advantage generalists and late specialists have is more concrete: you are more likely to pick a suitable study, sport or profession if you first orient yourself broadly before you make a choice. (That’s how dating works – only a very small number of people marry the first person they meet.)

In part, late specialisation explains Federer’s long career: for him, tennis is not a job, despite the monotony it may bring, but a passion. Greater enjoyment of the game is one of the benefits associated with late specialisation, along with fewer injuries and more creativity.

Compare this with Woods and many other child prodigies who specialised early. "For me [tennis] was the wrong life; it was not mine," another champion tennis player André Agassi told Der Spiegel magazine. It is difficult to separate this sentiment from an upbringing dominated by hours and hours of practising a single sport from age two or three. But which child, teenager or person in their 20s knows what they will be doing for the rest of their lives?

The issue: it is hard to get out of something you’ve taken up fanatically. Epstein provides ample evidence that late career switches work out well, but understandably many people get anxious just thinking about it. Can I really start doing something else? Or am I too far behind?

Persevering along a chosen path can also lead to other problems: frustrations about failure. If practice makes perfect, why am I not a genius? In a critical review, three researchers wrote that this philosophy of perseverance can have negative consequences, which is one of the dangers in the great belief in specialisation, grit, growth mindset and malleability.

The illusion of early progress

Suppose Epstein is right – and he does make a very compelling argument. How do you convince a world geared towards early specialisation to switch to late specialisation?

Hint: it’s incredibly difficult.

The tricky thing about generalist long-term thinking versus specialist short-term thinking is that the latter produces faster and more visible results. A football team with lots of precocious children, with a coach advising everyone to keep passing the ball to the best player, will win plenty of matches. The coach will be evaluated positively. Parents think the children are improving. But winning is not the same as getting better.

Several sports are struggling with this. In tennis, you can win up to a certain level by making fewer errors ("unforced errors") than your opponent. At a higher level, this doesn’t work as well – there you make the difference with winning strokes ("winners"). How do you get better at winning strokes? By trying them out at a younger age. And doing that means you will sometimes lose a match.

Winning is not the same as getting better

In short: specialising in short-term success gets in the way of long-term success. This also applies to education. Epstein found a great natural experiment to illustrate the hold that the short term has over the long term.

American Air Force Academy students were given mathematics lessons in a specific format. Every year, they would be given a new module, every year they would have a different teacher, and all the teachers administered all the modules (maths 1, 2 and 3). This randomisation allowed researchers to isolate the influence of an individual teacher on the overall learning effect.

The results were surprising.

The better a teacher scored on their own subject (i.e., the higher the grades their students got in that subject), the more mediocre students’ scores were across the complete programme (all modules). The explanation? Those teachers gave their students rigidly defined education, purely focused on passing exams. The students passed their tests with high marks – and rated their teachers highly in surveys – but would fail later on.

Teachers who taught more broadly – who did not teach students readymade "prescribed lessons” but instilled "principles" – were not rated as highly in their own subject, but had the most sustainable effect on learning. However, this was not reflected in the results. These teachers were awarded – logically but tragically – lower ratings by their students.

There’s that hostile learning environment again.

And now: not a pithy one-liner, just some life advice

Another, more theoretical problem regarding Epstein’s message is that he does not offer clear life advice. Now, we may ask ourselves how useful or even desirable is life advice presented as a slogan.

But the 10,000 hour gang has considerable power with their message "quitters never win, winners never quit".

Epstein’s more wholesome message seems weak and boring in comparison. Some things are simply not meant for everyone, doubt is understandable and even meaningful, you can give up and change your choice of work, sports or hobby, and an early lead can actually be a structural disadvantage.

How do you summarise that in a pithy one-liner?

Epstein makes an attempt in his conclusion: "Don’t feel behind." Don’t worry if others seem to be moving faster, harder or better.

Winners often quit.

This article has been updated with the correct name of Johannes Kepler.

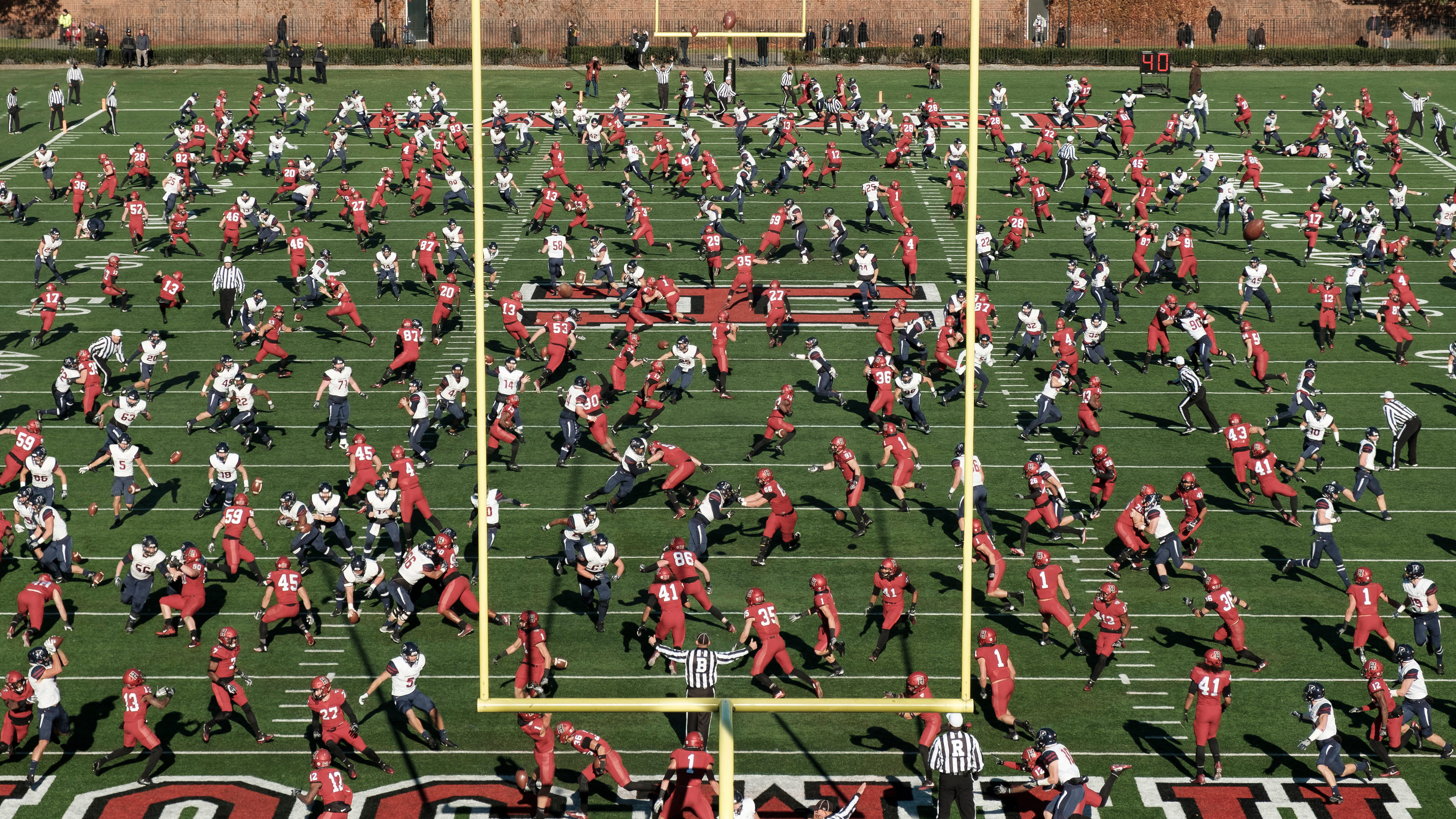

About the images

The ecstatic chaos in Pelle Cass’s photographs is made possible by a time-lapse technique that captures athletes in movement over the course of a game or competition. Using a tripod, he takes up to 1,000 pictures that he later rearranges into one single collage, in which the athletes are shown performing simultaneously. The strangeness of the end result is partly triggered by how real the images look, even though they’re very composed. In fact, not one pixel is changed through the merging process; each figure is kept in their initial position. The resulting rhythms and patterns subvert the traditional narratives of sport events by giving the gatherings a sense of joy. No matter who the winners are, play prevails over success. (Myrabelle Charlebois, image editor)

About the images

The ecstatic chaos in Pelle Cass’s photographs is made possible by a time-lapse technique that captures athletes in movement over the course of a game or competition. Using a tripod, he takes up to 1,000 pictures that he later rearranges into one single collage, in which the athletes are shown performing simultaneously. The strangeness of the end result is partly triggered by how real the images look, even though they’re very composed. In fact, not one pixel is changed through the merging process; each figure is kept in their initial position. The resulting rhythms and patterns subvert the traditional narratives of sport events by giving the gatherings a sense of joy. No matter who the winners are, play prevails over success. (Myrabelle Charlebois, image editor)

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Not a member of The Correspondent yet?

The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!

Dig deeper

Mental toughness is overrated: a World Cup-winning coach debunks sport’s most sacred trait

Paddy Upton made it to the top of the ‘gentleman’s game’. As many others struggle with the sport’s gruelling schedule and the pressures of fame, the South African coach shares invaluable lessons for mental health in sports and life.

Mental toughness is overrated: a World Cup-winning coach debunks sport’s most sacred trait

Paddy Upton made it to the top of the ‘gentleman’s game’. As many others struggle with the sport’s gruelling schedule and the pressures of fame, the South African coach shares invaluable lessons for mental health in sports and life.