There is a new normal now in global politics. What was once the “far-right” – a right-wing politics that exist outside of and are more radical than mainstream conservativism – has moved rapidly to the centre. A new form of anti-minority, anti-immigrant nationalism is sweeping across vast swathes of the world, rewriting the rules of the postwar political order.

Read this story in a minute

Ten years ago I warned that this far-right wave was coming. Hours before the Conservative Party took the reins of power in Britain on 6 May 2010, I had predicted that election would be the first stage in “the increasing legitimisation of far-right politics by the end of this decade”.

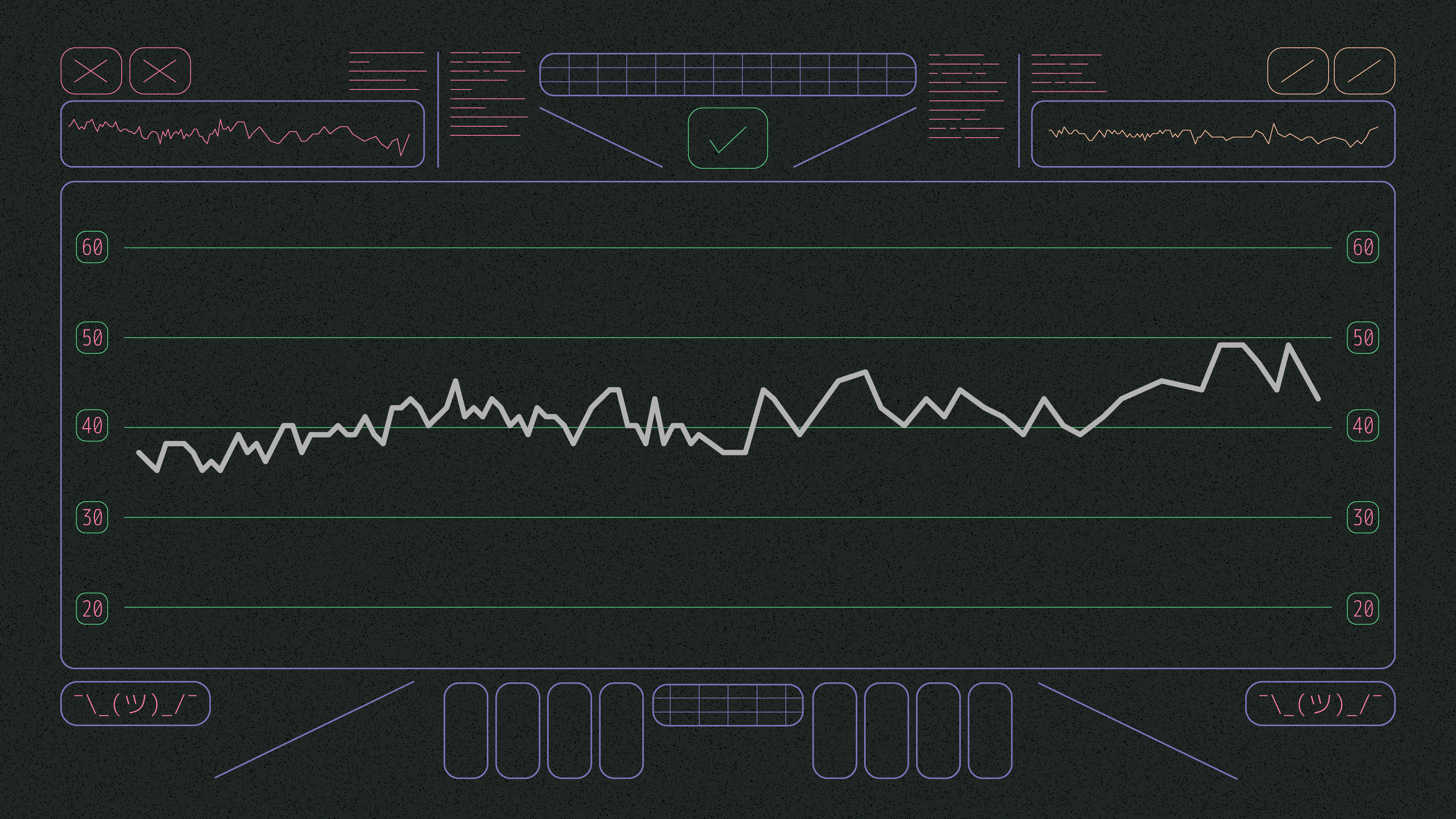

Sure enough, the global shift to the far-right has involved a resurgence of nationalism whose fundamental electoral strategy is the demonisation of minorities and foreigners. The popularity of anti-European Union (EU) nationalists in the European Parliament has grown exponentially, from just 11% of seats in 1999. By 2014, this had grown to some 23% – just under a quarter of all seats in the European Parliament. Two years on, Britain voted to leave the EU in the same year that Donald Trump became US president. Then by 2019, the EU elections saw nationalists capture 31% . Later that year, after a period of sustained attacks on parliamentary institutions, Boris Johnson – a politician with a history of inflammatory race-baiting against black people, migrants, and Muslims – led his party to a landslide victory on a hardline anti-EU platform.

As 2020 picks up pace, far-right politics is no longer the province of the fringe. It has encroached onto, and defined, the parameters of the political centre. And if these growth trends persist, it will continue to determine how the centre works throughout the coming decade.

The alt-Reich: reminiscent of, but distinct from 1930s fascism

Shortly before Trump was first elected, I had been commissioned to investigate the trans-Atlantic networks behind the far-right by Tell Mama UK, a London-based charity that exists to track anti-Muslim hate crimes. The report, Return of the Reich: Mapping the Global Resurgence of Far Right Power , found that nationalist movements and political parties across the US, UK and Europe were increasingly operating in unison.

While they all mobilised on the basis of anti-Muslim, anti-migrant sentiment; many were also rooted in traditionally antisemitic political movements, and some secretly worked with active neo-Nazi groups. Many self-identify as ‘alt-right’, a term coined by the white nationalist Richard Spencer , and the idea of ‘the great replacement’ is at the heart of alt-right ideology. This is a theory that goes by many names but which boils down to this argument: that “white European populations are being deliberately replaced at an ethnic and cultural level through migration and the growth of minority communities. Certain ethnic and religious groups – primarily Muslims – are typically singled out as being culturally incompatible with the lives of majority groups in Western countries and thus a particular threat.”

By seeking to protect the west from a perceived Muslim takeover through mass migration, cultural subversion, and political infiltration, the far-right have positioned itself as defenders of freedom and civilisation from a fascist takeover – and, as the ideas have moved from the fringe to the mainstream, the rhetoric of hate has made its way into everyday political life.

Adama Dieng, the UN’s special adviser on the prevention of genocide, described this trend as reminiscent of the 1930s, an age when antipathy toward perceived outsiders on racial grounds, particularly Jews, was not only widespread but led to the mass appeal of fascism. Much has changed in the world since the 30s and the alt-right has changed with it.

One of the most important distinguishing features of the new global far-right network is that it now uses the political centre to disseminate its language, beliefs and political programme. This is done through a range of strategies that include mobilising hundreds of millions of dollars to fund fringe groups, carrying out opaque lobbying efforts which often bypass political regulations, and the extensive use of social media ( from Facebook and Twitter, to Gab and 8chan ) to radicalise people susceptible to its messaging.

These strategies have successfully created what I call the ‘alt-Reich’: a global network of nationalist movements, civil society groups, and political parties by which far-right groups rooted in racism are attempting to influence mainstream conservatism. So far, as the infographic below shows, they’re succeeding.

Not every group or government in the network is necessarily racist – the political groupings within the European Parliament for example are a broad church that range from the traditionally conservative, to the openly bigoted. Other groups in the network actively deny and conceal their racist roots. But it is these complex, networked connections between the entities and individuals that has enabled a worldview historically rooted in white nationalism to increasingly impact national governments, from the White House to Whitehall and Brussels.

Here’s an example of how this network works. One of the most quietly influential organisations, in spreading the messages of the alt-right across the Atlantic, is the New York-based Gatestone Institute, founded by heiress, Nina Rosenwald. In one investigation into how anti-Muslim propaganda spreads between Europe, the US and then onto Trump’s Twitter account, Buzzfeed found a story of a “Muslim biker gang” in Germany which had been translated and repackaged by the Gatestone Institute. Now the article “included warnings about the country’s supposed slide into Islamic fundamentalism”. That tale of a Muslim group wanting to establish “a parallel Islamic legal system in Germany” was widely reproduced and has outlived even the activities of actual bikers, who according to the original reporting in Die Welt, were reminiscent of Hells Angels and had just one member was considered a possible threat by German authorities.

Gatestone chairman, John Bolton, was Trump’s national security adviser from April 2018 to September 2019. Even now, Gatestone remains close to Trump’s inner circle. Within a week of resigning, Bolton hosted a gathering of Trump allies at a Gatestone luncheon, including another billionaire conservative heiress Rebekah Mercer (described by the Financial Times as “the mega-donor who bankrolled Trump’s campaign” ), Harvard lawyer Alan Dershowitz ( Trump’s lawyer who argued at the Senate impeachment trial that the abuse of power was not an impeachable offence ) and Chris Ruddy ( a friend of Trump’s and CEO of Newsmax, a conservative media company whose revenues grow as the US president critiques the mainstream press ).

The chief of staff of Bolton’s National Security Council from May to October 2018 was Fred Fleitz, now president and CEO of the Center for Security Policy (CSP), a Washington thinktank described by the Southern Poverty Law Center as a “conspiracy-oriented mouthpiece for the growing anti-Muslim movement”. Fleitz co-authored a 2015 publication for CSP arguing that naturalised American Muslim citizens who adhere to sharia law should be subject to loss of citizenship and deportation. The CSP’s founder is Frank Gaffney, a former Reagan defence official, and a man “gripped by paranoid fantasies about Muslims destroying the West from within.”

Gatestone has partnered with the far-right antisemitic Canadian website Rebel News , which has released materials defending Holocaust denial and hired former Trump adviser Sebastian Gorka, who in 2017 was fired after being outed for ties with Hungarian Nazi collaborators.

CSP has a long established partnership with the International Free Press Society in Denmark, an anti-Muslim coalition whose senior staff are affiliated with the neo-Nazi Belgian Vlaams Belang party. The party was born out of the Flemish Legion - a German Waffen-SS division recruited from Flemish volunteers. In 2004, following a legal ruling that deemed Vlaams Blok to be racist, the party rebranded as Vlaams Belang (VB) and is today the most popular party in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking area of north Belgium. The party has followed the communications playbook of the alt-right, focusing heavily on attracting young audiences online. In 2019, VB spent more than any other Belgian party on social media advertising.

Meanwhile, both Gatestone and CSP have ties to British thinktanks with leverage in Conservative-run Whitehall, including Policy Exchange and the Henry Jackson Society, which have exerted significant influence on Boris Johnson’s post-Brexit policy vision. All the while, Johnson’s chief adviser, Dominic Cummings, invites “misfits and weirdos to apply to work at Downing Street, and appoints Andrew Sabisky, a man who thinks black people had lower average IQs than white people and that compulsory contraception could prevent "creating a permanent underclass".

There are public figures – Great Replacement conspiracists you might call them – on both sides of the Atlantic and beyond, who make deft use of dehumanising racist memes, distorted demographic data, and debunked science to validate their hate. Best known: former Trump adviser Steve Bannon, who once told a journalist that he and his associates were the “anti-fascists”. And then there’s Katie Hopkins, who has a long track record of denigrating blacks, Muslims, immigrants, and Jews, and – of course – openly endorses the crop of what she’s called “right-minded” leaders. Clearly music to Donald Trump’s ears as he retweeted a message Hopkins posted in July 2019 – before Twitter deleted her tweet history.

From culture to climate and democracy: the alt-right’s new frontiers

Aside from coopting “the grievances of different fringe communities on the internet by connecting anti-migration, anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT), anti-abortion and anti-establishment narratives”, alt-Reich governments have a track record of trenchant support for continued fossil fuel expansion, regardless of the environmental consequences.

When the German thinktank Adelphi mapped out the climate agendas of far-right parties in Europe last year, it found that two-thirds of far-right members of the European Parliament (MEPs) “regularly vote against climate and energy policy measures”. Meanwhile, some 30% of global carbon emissions come from countries led by populist, nationalist leaders.

Economically, the alt-right tends to be consistently sceptical of international institutions, more protectionist – often fetishising national corporate power – and wanting to restrict public services for the benefit of worthy ‘natives’ rather than foreigners or minorities.

This is an indication of what lies ahead: the past ten years of persistent far-right expansion in the west, represents – to my mind – the beginning of a more permanent illiberal turn. Particularly when it comes to Islamophobic attitudes, prejudice has intensified as quickly as it has been normalised. Few remember – or know – that in the 1990s, only 17% of Brits exhibited prejudicial views of Muslims. The world average was 21% at the time, with highest rates of prejudice found in then Czechoslovakia at 49%, and Bulgaria at 41%. In the 90s, US Americans demonstrated some of the lowest levels of prejudice towards Muslims, polling at 14%. Fast-forward 30 years and we see a rise in anti-Muslim hate crime; a rise in populist anti-Muslim political parties; the ban on face-covering veils in public places in France, and on the building of new minarets in Switzerland. Let’s not forget Trump’s Muslim travel ban.

Again: this is the ‘new normal’ – the backdrop against which this decade’s political struggles must be waged.

Having now set the tone of the debate by normalising fear of minorities and foreigners, the alt-right is better-placed to secure election wins. With more far-right groups either in power or with direct access to those in power, over the coming decade they are likely to focus on trying to rewrite the very rules of democracy. We see these processes underway already, as leaders rebrand political adversaries as enemies, and openly deride core institutions of democratic governance: the independent press, the judiciary, the bureaucracy, the legitimacy of democratic contestation, and the centrality of facts to political discourse.

Simultaneously, and perhaps in places with fewer checks and balances on the power of the state or the army, we are likely to see an escalation of state-backed security, paramilitary and communal violence against Muslim minorities, some of which has already been described by experts as “genocidal”: the mass incarceration of up to three million Muslim Uighur minority citizens in detention camps by China ; the mass expulsion of nearly a million Rohingya refugees by Myanmar; the systematic persecution of Muslim citizens in India including the risk of exterminatory violence in Kashmir and Assam.

It is a pretty gloomy picture but the very expansion of the alt-right is also likely to open up unprecedented opportunities to change course.

I spoke of a new far-right wave in 2010, seeing it – as others also have – as a consequence of a deeper global structural crisis. This new and improved alt-right ideology that’s found its way from the political fringe to the mainstream is a direct consequence of a convergence of multiple complex crises including: the financial crash of 2008, the climate emergency, state collapse, terrorist attacks and biodiversity loss.

People are feeling a deep sense of unease at the pace of change. This is why the alt-Reich’s most successful political experiments claim to be returning people to a glorious past - an attempt to cling onto a way of life that is gradually, inexorably crumbling; an attempt to rationalise its failures by imagining that the causes of those failures are not the system itself, but particular groups of inherently problematic people.

How we take on the alt-right

If the alt-right has capitalised on people’s desires to remake and redefine their societies, then so too can new social movements that join the dots between the various crises humanity faces and proposing strong opposing ideas to those of the alt-right.

Promising a return to some imagined world of old, parts of the extreme right will continue to deny climate science while resisting calls for climate action; yet others may well come to incorporate climate discourses into their xenophobic agenda, using the acknowledgement of crisis to buckle down on closing national borders. But the alt-right’s insistence on business-as-usual will ultimately be its undoing, as the gap between its promises and ecological-economic reality widens. This is likely to drive renewed discontent even among those constituencies currently propping up extreme rightwing governments. In turn, the alt-right will become much more brittle and susceptible to failure.

This is cause for hope, but not complacency. We cannot afford to simply wait while the ‘alt-Reich’ takes us all down with it.

From a systems perspective, change becomes possible when we all recognise that the rise of the far-right is a symptom of a global industrial civilisation in demise. Referencing ecologist CS Holling who identified that all systems go through a cycle of rapid growth, conservation, release and reorganisation, the systems theorist Jeremy Lent would say now is “the time when new ideas can have an outsize impact.”

A Future Earth report points to “the rise of countervailing voices inside the formal political ring, among liberal elites, and especially in grassroots movements.” These voices, quoting environmentalist Bill McKibben, need to be “rooted in broad movements, not elite opinion”. Such broad alliances are possible when citizens start to imagine together what the next life cycle of civilisation could look like.

The nationalist impulse is unlikely to disappear – nor will hate for that matter. But in terms of how societies are organised, it is entirely possible to move towards participatory, inclusive societies; built on more local institutions of political and economic empowerment. This, ultimately, means telling new stories, not only of how we got to where we are, but where we might be able to go if we work together, rather than against one another. It also means building bridges across disparate movements addressing climate, race, finance, and all the other global systemic issues, so that we cease operating in silos, but work more holistically to develop and implement these new stories.

The alt-Reich is the last hurrah of a global system in decline, but it will not go quietly – nor should we take it lying down.

Dig deeper

The unthinkable has become reality. How can we build back better?

How are people crafting solutions that we can all draw from to build back better after the pandemic? From food security, to education and housing, I’m exploring our options

The unthinkable has become reality. How can we build back better?

How are people crafting solutions that we can all draw from to build back better after the pandemic? From food security, to education and housing, I’m exploring our options

The real story of US democracy isn’t the drama. It’s the complete unresponsiveness to it

Democracy in the United States has often been declared at risk – if not actually dead, then at least on life support. But American democracy isn’t dead, it’s in a deep and worrying coma.

The real story of US democracy isn’t the drama. It’s the complete unresponsiveness to it

Democracy in the United States has often been declared at risk – if not actually dead, then at least on life support. But American democracy isn’t dead, it’s in a deep and worrying coma.