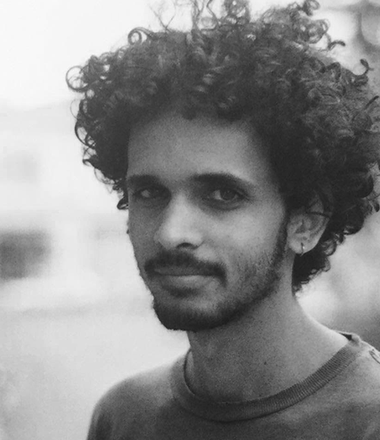

Ruben Mackellar picked up the phone not knowing what to expect. On the other end was another man, also in his mid-20s, at home alone and deeply distressed. He told Mackellar that he intended to kill himself.

Read this story in a minute.

The 24-year-old suicide hotline volunteer had been trained for situations like this. At Lifeline Australia, he had recently spent nine months receiving intensive on-the-job training, learning how to handle whatever would be on the other end of the phone when he picked it up. It had been months of actively taking calls while he himself was being monitored.

Mackeller took a breath, then, while trying to reassure the caller and keep the conversation going, he reached for the little red button next to him which signalled to his supervisor that he needed assistance – fast. About 13 minutes later, the caller put the phone down. Then all there was was silence.

“From then on, I have no idea what happened,” Mackellar tells me. He explains that this is common: once a call is finished, responders have no way to follow up.

For some, this is problematic as responders get no sense of closure. But for Mackeller, it’s a blessing. “I’m certainly glad that I don’t know because if [after] every call I was given an update, well then … ” He trails off before adding: “Jesus Christ.”

Mackellar had agreed to speak with me over the phone in order to help me understand what a day in the life of a suicide hotline responder was like. A few months prior, I had been considering volunteering for a hotline, so I wanted to know more about the work. More specifically, I was curious about what the mental health burden was on these individuals who provided a vital service, often part-time and for free.

While the people who make calls to suicide hotlines are — by definition — deeply distressed, much less is known about the mental wellbeing of those who respond to these calls. What would I be getting myself into?

The cost of caring

The number of calls to crisis response hotlines all over the world seems to be rising, and with it pressure on responders has also been mounting. After the South African Depression and Anxiety group received 41,000 calls in the first eight months of 2019, Cassey Chambers, its director of operations said: “We have to make sure people understand that suicide in South Africa is a growing concern and it needs serious priority.” In the US, the number of calls to suicide prevention hotlines grew between 2017 and 2018 from one to 2.2 million. And Lifeline Australia put out a statement on 30 January 2020 to say that since December of the previous year calls had already increased by 10% since last year.

Lifeline Australia, the country’s largest suicide prevention line, has over 11,000 volunteers like Mackellar, all working four-hour shifts to provide suicide prevention services, mental health support and emotional assistance, over the phone, in person or online. For every single one of these volunteers, it can safely be assumed that the very nature of dealing with highly distressed people makes this work especially demanding. But just how demanding? And how do the levels of stress or anguish differ from the rest of us? In other words, don’t most of us have relationships that — to some degree — require us to make significant emotional investments that can be draining?

From his lived experience, Mackellar explained that not every call is from someone who is imminently suicidal. In fact, those make up only a small fraction of the calls he takes on his shifts. Relationship breakups, loneliness, domestic abuse and various mental health and substance abuse disorders are all common themes. But often the challenge isn’t the volume of calls. Mackellar tells me it can take just one traumatising call to severely affect the responder’s mental wellbeing. “The impact of a call like that can still play in your mind, you know, for weeks after,” he says.

As for what the science says, to my disappointment, it turns out there is virtually no research specifically investigating the mental health of suicide hotline responders. The only research I could find focusing on this particular group of individuals was being done at Wollongong University in Australia, by a team led by Taneile Kitchingman.

It turns out there is virtually no research specifically investigating the mental health of suicide hotline responders

Kitchingman first became interested in the topic following her own troubling experiences as a suicide hotline responder. “I began to wonder whether I was the only crisis line support worker who was quite distressed by some of the calls I was answering,” she tells me.

To find an answer, Kitchingman led a study in 2018, where her team measured the level of psychological distress experienced by a cohort of 110 suicide hotline responders directly before, after and a week following a shift at Lifeline Australia. Though the study included relatively small sample sizes and only looked at how volunteers were affected by a single shift, rather than in the long term, the results are still worth consideration.

To her surprise, Kitchingman discovered that most suicide hotline responders actually showed levels of distress similar to those found in the average population. However, she did find that a subgroup of these responders exhibited an unusually high number of depression-like symptoms, including anxiety, stress, and suicidal thoughts. Interestingly, this subgroup was also less likely than other responders to seek help when experiencing distress. The clinical psychologist also found that responders scored significantly higher on scales measuring levels of fatigue and inertia directly after a counselling shift, compared to just before one.

Who responds to suicide hotline responders?

To put Kitchingman’s study in context and better understand the emotional and mental toll on phone responders, I spoke with Charles Figley, founder and director of the Traumatology Institute at Tulane University in the United States, who’s extensively studied the mental health of caregivers more broadly.

“You can’t look [callers] in the eye, you can’t have a sense of their micro-expressions, how well they’re doing,” he said to explain why the uncertainty of not knowing how serious a call will be prior to answering it or why the inability to follow up on a caller’s situation make this work particularly challenging.

The strain on suicide hotline responders is not unique to the job. Just like the police, firefighters, therapists, and other first responders, Figley notes that suicide hotline responders face highly challenging circumstances in different but psychologically relevant ways, such as the frequent use of empathy or being exposed to traumatic events. As with all these roles, a key determinant of how suicide hotline responders deal with the situations they are confronted with is their capacity for empathy.

The greater a first responder’s capacity for empathy, the trauma psychologist says, the more they connect with and vividly experience the traumatic stories of those they seek to help. Living through these experiences vicariously may seriously damage a caregiver’s mental wellbeing, ultimately leading to “compassion fatigue”— a term Figley defines as a form of caregiver burnout.

Compassion fatigue first appeared in a 1992 article by writer and historian Carla Joinson when describing the arduous work of nurses in an emergency department, but the concept had already been articulated in 1980, in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which stated that “knowing of others’ traumas can be traumatising.”

Figley puts it another way: “When someone is doing a great job and being tremendously compassionate, there’s blowback from that. There’s a cost to caring.” It’s a cost that can manifest itself in various ways including feelings of exhaustion, helplessness, anxiety, numbness, and depression.

Compassion fatigue explains the risks first responders face in their work – and the signs that were observed in the Wollongong University study – but it also makes clear a challenge that is hard to solve. The very quality that makes an excellent suicide hotline responder is the ability to listen – actively, compassionately, and, yes, empathetically – to traumatic stories, but doing so ultimately leads them to feel overwhelmed.

‘When someone is doing a great job and being tremendously compassionate, there’s blowback from that. There’s a cost to caring’

"Burnout, fatigue, maybe having days when ... you sometimes might not have the energy to contain what is happening inside you, so it barely leaves you with the energy to contain what someone else might be bringing.” This is how Tanuja Babre, programme coordinator at iCALL, a well-known helpline in India, describes the impact of the work.

This resonates immediately with Mackellar: "I can definitely relate to that." But, based on the definitions and the research I was finding, what most struck me is how pervasive compassion fatigue actually is.

Sure, suicide hotline responders and other first responders are particularly vulnerable to feeling emotionally depleted, but aren’t we all to a greater or lesser extent? Figley thinks so. Whether it’s caring for an ageing parent, an anxious friend, or a troubled stranger, or whether it’s dedicating one’s life to remedy societal ills such as ending homelessness, discrimination, or inequality, all humans face the challenge of walking a tightrope between caring for others and burning out ourselves.

Dealing with the trauma of others

Still, Figley cautions against desperation. He insists that there is plenty that we can all learn from how first responders deal with extreme cases of trauma.

First, having a support system is key. For first responders, it is important that the suicide prevention hotline they work for gives support by, for example, providing them with group debriefing sessions, where responders can share calls they found particularly troubling with their colleagues. Callers at Lifeline Australia also work with experienced supervisors who regularly check in with their mental health.

Similarly, says Figley, people who feel emotionally burdened should reach out. Whether it’s to a therapist, a close friend, or a person having similar experiences, having someone who can regularly monitor your mental wellbeing can go a long way.

‘You have to be clear and consistent and value yourself as much as the person you’re taking care of’

Secondly, Figley suggests reframing how you think of yourself as a caregiver is fundamental. Sometimes the best way to care for others is to think of yourself first. “You have to be clear and consistent and value yourself as much as the person you’re taking care of,” he explains. It’s important to know how naturally empathetic you are as a person. Doing so can help plan for situations where an excess of empathy can lead to burning out. In order to know what situations and events might trigger you, it’s also important to develop an ability to regularly introspect and reflect on your own experiences — a skill Figley thinks can be harnessed through mindfulness.

Babre makes a similar point, saying: “It’s important to understand your own capabilities of what you can and cannot do. Knowing when your own resources are feeling depleted … not feeling any shame in terms of accessing help for yourself.” Babre goes on: “It is very important that you create spaces for yourself where you can open up without shame, without distress and despair and talk about what you are going through, which is a non-judgmental space. And not only just one but create multiple spaces for yourself.”

After all I’ve learned – both about the strain of the work and about the ways of coping with that strain – I’m unsure about whether I have the emotional resilience to become a suicide hotline responder. This is a serious responsibility, one I feel more acutely aware of after I began working on this story. The idea that accidentally striking the wrong tone or failing to de-escalate a situation may ultimately decide whether someone lives or dies frightens me.

For others — like Mackellar and many like him — the job is not just rewarding; it is humbling. Volunteering for Lifeline Australia has helped him contextualise the small, petty stresses of daily life. “If I were to compare [my stresses] to the people that I’m speaking to over the phone, they’re actually quite small and minute.”

And despite the hardships accompanying the job, he is grateful for the chance to help. “[I’m] very fortunate to be living in a world where you can have the opportunity to give back and give time to others.”

If you have been affected by any of the issues in this article, this website provides contact details of free helplines around the world.

Not a member of The Correspondent yet? The Correspondent is a member-funded, online platform for collaborative, constructive, ad-free journalism. Choose what you want to pay to become a member today!Dig deeper

Mental toughness is overrated: a World Cup-winning coach debunks sport’s most sacred trait

Paddy Upton made it to the top of the ‘gentleman’s game’. As many others struggle with the sport’s gruelling schedule and the pressures of fame, the South African coach shares invaluable lessons for mental health in sports and life.

Mental toughness is overrated: a World Cup-winning coach debunks sport’s most sacred trait

Paddy Upton made it to the top of the ‘gentleman’s game’. As many others struggle with the sport’s gruelling schedule and the pressures of fame, the South African coach shares invaluable lessons for mental health in sports and life.

Trauma can be inherited. We need to understand what we’re passing on

When it comes to negative experiences in childhood, the body seems to keep score. But even small changes can positively affect health in later life.

Trauma can be inherited. We need to understand what we’re passing on

When it comes to negative experiences in childhood, the body seems to keep score. But even small changes can positively affect health in later life.