Hi,

Four years ago, I was forced to take my first break from full-time work. As I then described in a post on LinkedIn, I wasn’t gifting myself a "sabbatical" or going on a journey of "self-awareness". After 11 years of non-stop work, my brain had simply run out of gas. It wasn’t some grand epiphany. It was messy and embarrassing, like wetting your bed when you are 33.

At that point, I had lived with depression and anxiety for 15 years. I had tried western medicine, reiki, aromatherapy, psychotherapy, past life regression – but I was so preoccupied with all these treatments that I forgot to pause and think about the one thing that ought to have been my real concern: recovery.

Given my constantly morphing symptoms and the never-ending wait to feel okay for more than a few minutes at a time, I’ve found recovery to be an unreal, intangible, wishful, fantastical idea for as long as I can remember. The word feels funny on my tongue.

Which is why I was intrigued when I got an invite to attend a workshop in the city of Pune last week, with the goal of establishing a model of mental health focused on the idea of recovery. Not merely treatment, not just prevention, but recovery – the poorly understood "after" of mental illness.

The people leading the workshop included Saumitra Pathare and Jasmine Kalha from the Centre for Mental Health Law and Policy, mental health activist Ratnaboli Ray, and Mike Slade from the University of Nottingham. Slade is one of the world’s preeminent experts on recovery and a leader of the Recovery Research Network, which is based in the UK.

In 2011, he was among a group of academics who published a paper on personal recovery in mental health – which is centred on the subjective experience of the individual, as opposed to clinical recovery defined by mental health professionals and their reading of clinical symptoms.

One definition of personal recovery stated in the paper is: “a deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills and/or roles … a way of living a satisfying, hopeful and contributing life even with the limitations caused by illness". (It isn’t an idea immune to criticism, given nagging questions around, among other things, who gets to decide when a person has "recovered". More on this another day.)

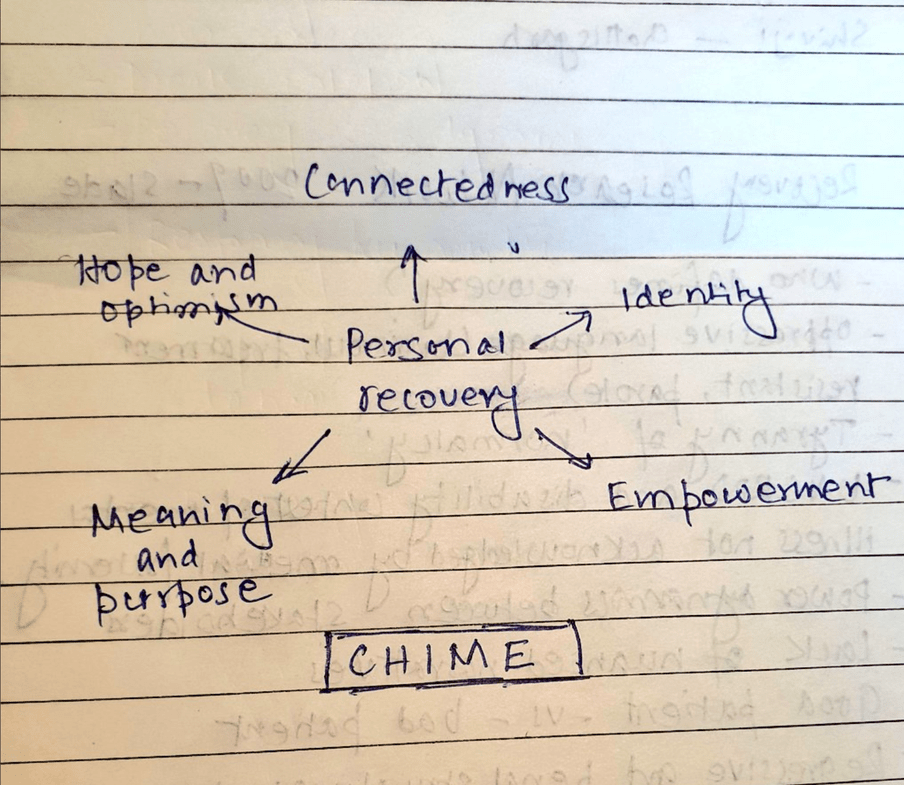

In their paper, Slade and his colleagues proposed an acronym to describe the critical components of the process of personal recovery: Chime – connectedness, hope and optimism, identity, meaning and purpose, and empowerment.

During the two-day meeting in Pune, one traditionally accepted marker of recovery that came up for critical scrutiny was the idea of work. We questioned whether the pressure to prove that a person with mental illness is "normal" again results in an undue valorisation of work – especially since the modern workplace itself is responsible for driving so many to the point of breakdown.

As my regular readers would know, I’ve been crowdsourcing examples of workplaces built on mental health-friendly policies and practices. As I sat through the workshop, I wondered whether Chime might not be a handy framework to assess the mental health quotient of workplaces.

What do you think? Is it reasonable to expect workplaces to champion the spirit of connectedness, hope and optimism, identity, meaning and purpose, and empowerment? Play an active role in recovery by fixing some of the isolationism, hopelessness, self-effacement, purposelessness, and powerlessness they are guilty of causing? Write to me.

PS: I am on holiday, so there will be no newsletter next week. Normal services resume the week after.

Would you like this newsletter sent straight to your inbox?

Subscribe to my weekly newsletter where I dismantle myths around Sanity, discuss the best ideas from our members, and share updates on my journalism.

Would you like this newsletter sent straight to your inbox?

Subscribe to my weekly newsletter where I dismantle myths around Sanity, discuss the best ideas from our members, and share updates on my journalism.