Here’s a riddle for you: a Samoan walked into a bar at 23:45 on 29 December 2011. After a quick drink and a bathroom break, they left 30 minutes later, on 31 December 2011. How’s this possible?

The answer is that on the Pacific island state of Samoa, 30 December 2011 doesn’t exist. And that’s because at midnight on the 29th, the country switched time zones – from UTC-12 to UTC+14 – making a jump of 26 hours.

With that one move, Samoa did away with an entire calendar day and changed the international date line. Interestingly, the seven islands that make up the US territory east of Samoa – American Samoa – kept its time zone at UTC-11, creating a 25-hour time difference between land masses that are only 220km apart.

Time zones seem straightforward enough. In fact, most of us only become aware of them when we travel, and this can either feel magical or chaotic. On the hour-long flight from Amsterdam to London, the traveller arrives at practically the same time they left, feeling as though they’ve cheated time. But many of us also know the feelings of confusion and stress when we forget to adjust our watches to a new time zone and find ourselves running very late. Or the reality of working with people across different time zones and struggling to figure out what time the meeting starts.

Over the past few years, as a developer, I have more than once encountered the troubles of implementing time zones on a platform. The Correspondent, with its members in over 130 countries, and staff in six, is no different. We’ve been thinking hard about how to simplify something this complex, but first, it’s worth diving into what time zones are and sharing why they’re more mind-bending than most people think!

What’s a time zone?

The most commonly used definition is that a time zone is a region of the globe that observes a uniform standard time for legal, commercial, and social purposes. All time zones are described as the number of hours adjusted to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) or Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) – more on this later. So for example, the time zone of the Netherlands is UTC+1, while Greece is UTC+2. There are also countries with multiple time zones, such as Mexico, which is split up into three: UTC-6, UTC-7 and UTC-8.

What’s the history of time zones?

Before the introduction of time zones in the 19th century, time was determined locally and would have varied depending on the norms, scientific practices and beliefs of different parts of the world. There were no internationally guarded rules about when one day began or ended, though the movement of the sun across the sky was the most commonly held way of telling time.

These standard times that could differ from one town, region or country to the next became problematic as rail travel expanded rapidly. To be able to set train schedules, it became increasingly important to be able to synchronise time.

First, in 1840, railway time was introduced, but seeking even greater synchronicity in 1884, the United States hosted the Meridian Conference, which gathered together delegates from 25 countries, with the aim of deciding a single global meridian to replace the multiple ones in use. It was there that it was decided that the prime meridian would go through Greenwich in London, England and GMT was introduced. As 72% of the world’s commerce was carried by ships that used the Greenwich Prime Meridian to chart time, Greenwich essentially – and arbitrarily – became the “centre of time and space”.

The world is now divided into 25 time zones – varying from UTC-12 to UTC+12 – each of them 15 degrees wide to denote a one-hour variance in mean solar time. But the story doesn’t end there. There are 11 additional time zone variations that allow for two more hour-long time zones, and half-hour or even quarter-hour differences. India, for example, uses UTC+5:30 and Nepal UTC+5:45

The mind boggles further if you consider that some time zones are referred to using abbreviations that tell you nothing about what the time adjustment is from UTC: the time along the east coast of the United States is known as Eastern Standard Time (EST). Essentially, EST is UTC-5, but nowhere does its name make that clear.

So, how are time zones determined?

Time zones are based on longitudes, meaning that Patagonia in Argentina is in the same time zone as Greenland.

Most countries choose to have a single time zone for that country to make it easier to talk about time. For some countries, such as Russia, whose land mass covers several longitudinal lines, this is impossible to do, and so Russia is divided across 11 different time zones. But not every country is concerned with longitude as a determinant of time zones. Time zones are also incredibly political tools. In 1949, Chairman Mao Zedong decided that the whole of China would use a single time zone (UTC+8).

To make things even more complex, what in the world is ‘daylight saving time’?

Aside from time zones, some countries use daylight saving time (DST) and switch between “summertime” and “wintertime”. While Europe changes from wintertime to summertime on the last Sunday of March and goes to wintertime on the last Sunday of October, the US and Canada switch on the second Sunday in March and on the first Sunday in November. In March, when the clocks go forward, that day only has 23 hours, then in October or November, when the clocks go back an hour, the day has 25 hours.

Daylight saving time in Australia is a fascinating thing. Some states have adopted DST but others haven’t, and there seems to be no logic to how it’s done. For example, while South Australia is usually a half-hour behind Queensland, in the summertime, the state adopts DST, moving it a half-hour ahead of Queensland.

The introduction of DST is a handy way for countries in the northern hemisphere to increase the number of hours of daylight in the summer by adjusting the time the day starts. Countries used this time trick during the 1970s energy crisis in an attempt to delay the evening, and it is still used today, but there’s currently a debate in the European Union (EU) about whether to keep DST or not. While implementing it may have lowered energy costs in the 70s, what’s left behind is confusion about what time countries are on, and evidence that a shorter day in the winter has adverse mental health effects. As of March 2019, the EU decided to scrap DST from 2021, but leave it up to countries to decide if they want to follow summertime or wintertime as their normal time. In a move strangely reminiscent of the 1800s, multiple US states, such as Tennessee and Oregon, are now considering a move to DST all year round.

And what does all this have to do with The Correspondent?

When we started to plan our platform for The Correspondent in May 2016, we thought of several subjects we needed to discuss and find a solution for because these differ significantly between the local Dutch platform (De Correspondent) and the transnational one. Top of the list: translating the interface from Dutch to English, mastering time zones, and setting up the server infrastructure for the platform.

At its core, here is the challenge we face: the users of our platform, our journalists and the team in the newsroom in Amsterdam are all using the platform in their own time zone. Even if they are all online at the same time, they understand what time it is differently. For example, when we published Sanity correspondent Tanmoy Goswami’s piece on the protests on India’s street that were in the news for several weeks, the article went live on our site – and was sent out in the daily newsletter – at noon CET. Our platform needs to store the date and time and show them differently in different places. In this example, noon was 6:00 on the east coast of the US where many of our members live, and 16:30 in Delhi where our writer was.

Here’s how we tackle this challenge:

- We show recent events on the site in terms of time elapsed, rather than with a date. For example: “This article was published 3 hours ago” instead of: “This article is published on 30 January 2020 at 14:00 CET”.

- We translate everything a user does on our platform – irrespective of their time zone – into UTC. We also do the reverse: calculating dates and times in UTC but presenting it to the user as their local time.

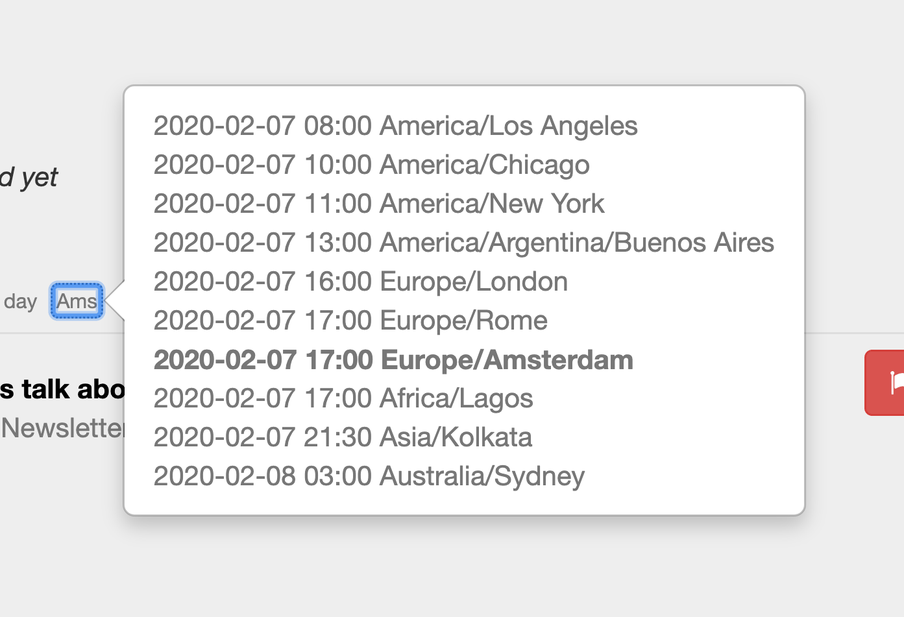

- Understanding that our audiences are all over the world, we want to launch stories at the best time for the most people. As a result, on our content management system, a pop-up shows the planned publication time across several regions.

Time is a fundamentally intangible concept. Time zones and DST are both the fabrication of a small handful of people in the west, and it can indeed be argued that in the modern world, we have become slaves to time. But such attempts to standardise time across the world do give us a shared understanding of concepts like "morning" or "the end of the work day". In a globalised world, and on a transnational platform, these tools, though limited, are invaluable.

Dig deeper

Welcome to the Member Quarterly

Every three months, the Member Quarterly shows how our members have helped shape The Correspondent’s journalism and ethos.

Welcome to the Member Quarterly

Every three months, the Member Quarterly shows how our members have helped shape The Correspondent’s journalism and ethos.