Two facts are pretty much all you need to know to put the climate crisis at the top of your voting agenda. One: the ecological emergency is the most pervasive threat we face as a species. And two: getting our planet back on track for a survivable future will require radical and urgent action.

It’s really as simple as that.

Since climate change disproportionately affects people who are shut out of traditional politics, a shift towards new forms of democracy could be the best chance to win back our futures. To transcend politics as usual and break through the logjams that have defined climate delay for decades, citizens of the world’s democracies will need to insist their voices are heard.

That’s already happening. Recent polls show that in the US and around the world, climate change has risen to the top of voters’ minds. It has played key roles in recent elections in India, Austria, Dominica, Spain, Canada, Australia, and Germany. For voters considering candidates to oust Donald Trump, the current US president, climate change is the number one concern.

In 2020, of course, the US elections will dominate the global news cycle, but there are national elections happening nearly every month around the world that will set the near-term trajectories of dozens of democracies. Every one of these elections are vital. In every election, a climate champion needs to be on the ballot, and they need to win.

All of these elections have the same basic purpose during a climate emergency: elect the person who has the best chance of enacting an agenda that brings us closer to a thriving world for all living things. The answer might not be immediately obvious, which is why open debate and freedom from the excessive influence of fossil fuel industry donors in the media and in elections are so important.

Four questions to figure out who your climate candidate should be

The way I see it, there are four basic criteria that make a good climate candidate, based on what the science says is necessary and how social change happens. We have much of the technology we need to work towards a zero-carbon world today. What we need is better leadership and a stronger movement. Here’s how to figure out who your climate candidate is:

- Do they understand what scientists say is necessary to keep warming from crossing 1.5C?

- Do they plan to implement inclusive changes that address the root of the climate problem with social justice for everyone?

- Do they have an inspiring vision that could actually build a movement and be implemented?

- What are the financial tradeoffs in paying for these policies?

Basically, these criteria boil down to:

- Is their plan enough?

- Does their plan put people at its centre?

- Does their plan stand a chance of actually becoming law?

In wealthy countries, “how do we pay for it?" has become code for austerity advocates and climate change deniers to dismantle social policy such as health care and pensions. In the frontline countries of the climate emergency, decades of delay have made climate reparations urgently necessary. Every estimate shows the cost of not addressing climate change is far greater than the up-front cost of action.

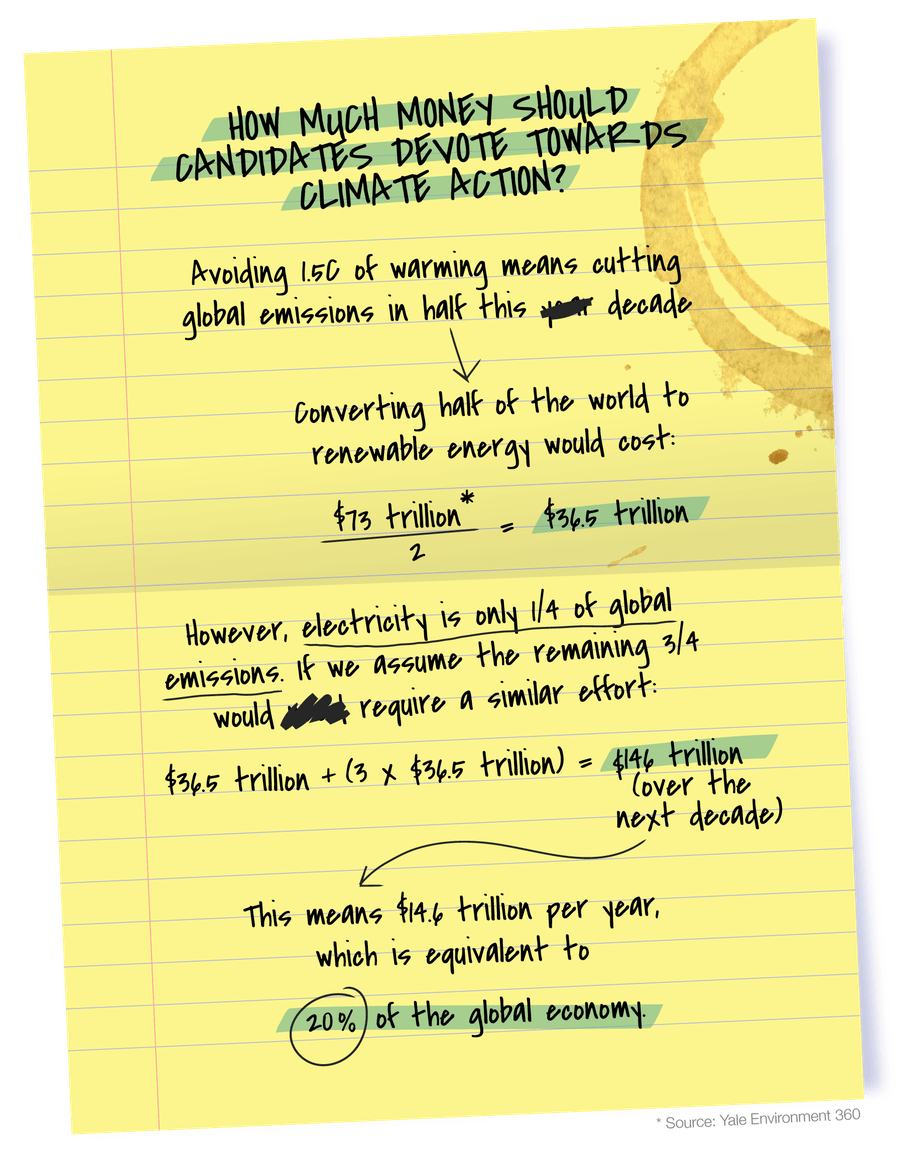

Current estimates show it would cost about $73tn to completely convert the world to renewable energy. That is a little less than one year’s worth of the total world economy. The investment would pay for itself in seven years. And since electricity production makes up only about 25% of all emissions worldwide, a comprehensive climate plan needs to be much bigger than that.

It is impossible to put all our money in renewables at once, and we have to cut global emissions by 50% this decade to be on track to avoid 1.5C. To do that, the minimum required investment would be about $36.5tn for renewable energy this decade globally, multiplied by four (to decarbonise 75% of the economy outside of electricity production) – roughly $150tn, or $15tn per year, about 20% of the world economy.

Since rich countries bear more responsibility, the fairest climate policy would make historically large emitters pay more. So look for candidates who have a plan to devote more than 20% of their national GDP in public and private spending to climate action. In the US, that benchmark is about $4tn per year.

Biden’s plan doesn’t go far enough

In the US, these criteria should automatically eliminate members of the Republican party for consideration because until recently, they didn’t even have a climate plan. In the past few days, details have begun to emerge of a new Trump administration strategy focused on tree-planting, but with no firm targets to actually reduce emissions. That’s disqualifying.

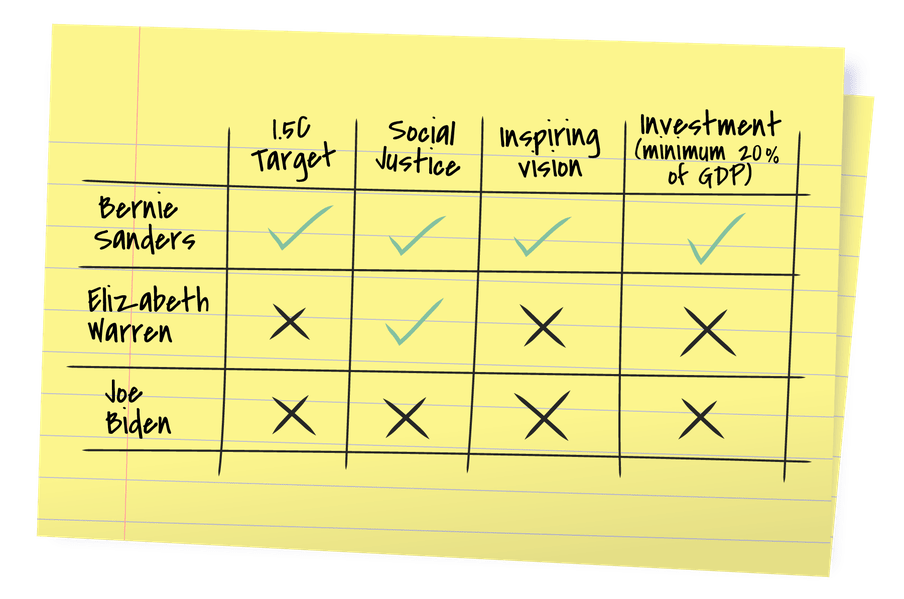

That leaves the Democrats, who are about to begin their nominating process to pick their presidential nominee, with the first votes due in Iowa on 3 February. Of the three leading candidates consistently polling above 15% of the national electorate – Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, and Elizabeth Warren – there are some stark differences.

The three leading Democratic candidates all call climate change an ‘existential threat’. But when you look at their actual plans, there are major differences.

The three leading candidates all call climate change an "existential threat" and acknowledge that bold action is necessary. But when you look at the candidates’ actual plans, there are major differences in how those visions would be implemented.

Biden’s climate plan is the least ambitious of the top three Democrats, planning to earmark $5tn of public and private spending over the next 10 years, mostly for renewable energy research and infrastructure. Worse, his goal of net zero emissions in the US by 2050 is only in line with the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5C if it’s achieved on a global scale, but far too late for the country that has contributed the most to causing this planetary emergency. It’s not clear that Biden’s plans would be a significant improvement on former US president Barack Obama’s climate policy.

The most ambitious US climate policy ever proposed

In contrast, either Sanders or Warren would be the best president we’ve ever had on this issue.

In terms of ambition, Sanders is the top choice. His version of the Green New Deal, which would invest $16.3tn in public money alone over 15 years, is the most ambitious climate policy ever proposed by any major candidate for president, and that’s by design: big changes can come faster by strategically rallying people who have been excluded from politics for decades.

Either Sanders or Warren would be the best president we’ve ever had on climate change.

A Sanders-proposed federal jobs guarantee would put people to work building not only zero-carbon infrastructure but also a culture of care and respect for human rights and environmental protection. Using the level of public investment as a benchmark, Sanders’s plan is at least six times more ambitious than Biden’s: more than $1tn a year, compared to $170bn. Assuming a four-to-one ratio of private-to-public money, as Biden’s plan does, Sanders’s plan would devote a little more than 20% of the US economy toward fighting the climate emergency.

Among climate wonks, Sanders’s consistent rejection of nuclear energy is a sore point, but his emissions reduction plans go beyond even what Paris requires. Sanders plans to rapidly and completely decarbonise the US power and transportations sectors – cutting 71% of national emissions by 2030, while guaranteeing enough international support to help developing countries cut their emissions by 36% in the same timeframe.

In times like ours, being realistic is the same as being radical

There’s also a persuasive case for Warren, who has made a strong name for herself as a champion of comprehensive environmental policy. She has released 13 climate plans so far, comprising a total of $10.7tn in public and private spending over 10 years on everything from transforming agricultural towns to cancelling hurricane-related debt in Puerto Rico to a “Blue New Deal” plan for oceans.

Her plans would cut US emissions in half by 2030, including 100% carbon neutral electricity and zero-carbon standards for all new buildings and vehicles by the end of the decade. She has said her first task is to alter the rules of the legislative branch to pass legislation more easily. However, Warren’s controversial stances on Indigenous issues, the effectiveness of capitalism, and the military’s role in climate action have undermined her claims of being a champion of social justice. And when using public funding as a measure, Warren’s climate plans are less than half as ambitious as Sanders’s.

In times like ours, being realistic is the same as being radical. Although climate change is the biggest existential threat we’ve ever faced, it’s definitely not the first one, and any effective climate leader must learn quickly from people outside of traditional politics. Sanders understands the roots of the climate crisis are in how we treat each other, not just the kinds of fuel we use to create electricity. When you see the world this way, a climate plan focused on tackling social inequality provides the most realistic path toward a liveable future that works for everyone. No other candidate for president understands this critical point as clearly as Sanders.

What’s absolutely clear is that even with Sanders as the next president of the United States, winning elections is not enough in a climate emergency. While climate scientists are finding new ways to scare us daily about the fate of the planet, we need to have leaders who consistently respond in a way that’s necessary. We need to build a movement to push our politicians to outline revolutionary visions of change.

Dig deeper

From Australia to Chile and Gran Canaria, greetings from the fire frontlines

Three countries, three stories of survival. Our postcards from the fire frontlines show how communities have responded to climate disasters.

From Australia to Chile and Gran Canaria, greetings from the fire frontlines

Three countries, three stories of survival. Our postcards from the fire frontlines show how communities have responded to climate disasters.

In 2030, we ended the climate emergency. Here’s how

If words make worlds, then we urgently need to tell a new story about the climate crisis. Here is one vision of what it could look and feel like to radically, collectively take action.

In 2030, we ended the climate emergency. Here’s how

If words make worlds, then we urgently need to tell a new story about the climate crisis. Here is one vision of what it could look and feel like to radically, collectively take action.