What is human civilisation if not the result of all the stories we’ve been told?

Centuries of evidence have shown that storytelling can change the course of history. Radical imagination, a term used by US author and social movement organiser adrienne maree brown, describes the power visionary fiction has to change the world. “Once the imagination is unshackled, liberation is limitless,” she writes.

Our story of the 2020s is yet to be written, but we can decide today whether or not it will be revolutionary. Radical imagination could help us begin to see that the power to change reality starts with changing what we consider to be possible.

So, I want to map out a possible path for what this decade could look like, if we do what we need to do.

As a trained meteorologist, I used current evidence to predict future events. As a writer, I’ve always chosen to let the scientific truth that we exist as an interdependent community of species on a finite planet guide me.

I want to map out a possible path for what this decade could look like, if we do what we need to do.

But after a half century of institutionalised climate denial and delayed action, I’ve learned that predicting human behaviour is impossible, and in a climate emergency, our choices become of hugely magnified importance.

During the 2010s, climate science grew increasingly dire, pointing toward planetary tipping points arriving more quickly than previously thought. A big part of why this crisis has spun into an emergency is that there has been too much of a focus on numbers – 1.5C, 350 parts per million, 12 years – and not enough attention on collective stories of a better world.

Still, the most important number is easy to remember: zero. Get to zero emissions globally as quickly as possible. Zero is revolutionary.

There are an infinite number of possible paths ahead of us, and what follows is just one of them, gathered with the help of friends from around the world.

This is a story about our journey to 2030 – a vision of what it could look and feel like if we finally, radically, collectively act to build a world we want to live in.

In a climate emergency, courage is not just a choice. It’s strategic. It’s a survival strategy.

Letting go of the life you thought you were going to have can cause a huge amount of grief. There’s a huge amount of courage in opening up to redefining your existence. There’s a huge amount of bravery to know that perhaps life even gets richer and deeper in unexpected ways.

It only takes 3.5% of the population to bring about political change. In New Zealand, approximately 3.5% of the population participated in climate strikes in autumn 2019, which was almost immediately followed by the country adopting one of the boldest climate goals in the world: to cut carbon emissions to net zero by 2050.

Building on New Zealand’s pioneering policy, 2020 is the year we acknowledge that the most urgent thing we can do in an emergency is to passionately tell others that it exists. The call to protect the planet will become a rallying cry as climate strikes around the world continue to escalate. More people will begin to demand a better world that works for everyone. This climate movement will catalyse urgent revolutionary policy to tackle the crisis.

We’ll still know in 2020 that we have to do a lot better, but admitting we’re in an emergency means we can start to tell ourselves new stories that will help get us out of the crisis. We will redefine happiness. We will watch hopeful television and movies about a possible world that does not yet exist. We will stop seeing the Earth as an external thing to be saved. We’ll realise that we are inextricably linked to the planet: saving it is, in fact, saving ourselves.

There will be mounting social pressure for climate laws far more ambitious than New Zealand’s law. To do enough on climate, some of the rich, high-emitting countries will have to be zero carbon by 2025. Nearly all wealthy countries will have to be zero carbon by 2030. It doesn’t matter which government is in power. Elections move too slowly. Voting feels helpless when the choice is between denial and delay. We will demand candidates that recognise the reality of this crisis.

In 2021, a new president of the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, the US, will pass a series of sweeping legislative changes to bring about a Green New Deal and help permanently decentralise political power from the extractive industries that have concentrated wealth for centuries.

It doesn’t matter which government is in power. Elections move too slowly. We will demand candidates that recognise the reality of this crisis.

George Monbiot has called this process “political rewilding” (where top-down governance is replaced with more participatory, spontaneous, bottom-up models), but it’s probably more easily understood as accountability. It’s the idea that industries holding the power to end civilisation as we know it shouldn’t regulate themselves. It’s the idea that government officials shouldn’t put corporate profits over the public good. It’s the idea that protecting the security of all life on Earth is really just about loving each other.

We will begin to redefine democracy through demonstrations, demanding climate justice. We will begin to redefine freedom in an era where the air we breathe embodies the deadly choices made by white men for hundreds of years.

This is how people will begin to listen again and exert moral leadership in all the positions of power we hold in our lives.

We will begin to redefine individual actions as actions on behalf of the collective. We will see care work and mutual aid as being at the core of climate action. The term “climate action” will start to lose meaning. It will just become “action”.

We will begin the process of climate reparations – partially repairing the loss and damage of colonialism and decentralising political power on a global scale. We will begin the process of returning land to indigenous control. We will see each other as people deserving of the right to thrive.

Indigenous people have, for centuries, effectively managed more than 80% of the world’s biodiversity. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples provides a particularly effective model for how to uphold peaceful nation-to-nation relationships while simultaneously building a world that works for everyone. We, as humans, have known how to do this for a very long time. We will remember how to do it again.

We will finally reach peak global emissions. We will finally stop accelerating towards our own destruction.

We will criminalise and delegitimise the fossil fuel industry. Fossil fuel executives will be tried for crimes against humanity. Ecocide tribunals will hold those to account for making parts of Earth uninhabitable. We will march through the streets of our coastal cities and along the shores of the future seas in solidarity and celebration as our oppressors are held to justice.

We will courageously name the people who created our burning world without fear of retribution because they will be made powerless by our vision of a better world. History will remember our decades of inaction to tackle the climate crisis as one of humanity’s most profound mistakes.

We will realise we have lost so much, but there is still so much worth fighting for. We will prioritise our own psychological and emotional resilience. We’ll take walks by the river. We’ll visit our friends.

We will, at last, have created the moral and cultural infrastructure for rapid decarbonisation of every aspect of our civilisation.

We will electrify everything: trains, heating, steel making, farm tractors. Since carbon dioxide stays in the atmosphere for hundreds of years, we will focus most intensely on the other greenhouse gases, such as methane and nitrous oxide. We will listen to farmers and use their wisdom to radically reform agriculture so that farms produce food, not commodities. While we’ll continue to plant new trees, we’ll focus our efforts on saving intact forests which suck a greater amount of carbon dioxide out of the air, and minimise the risk of using much needed arable land in ways that do not support the local ecosystem.

We will decrease global emissions by 10% in a single year and hold that pace for the rest of the decade. It will be the first year in history that we will be doing enough to slow the climate emergency.

We will have long begun seeing cars as death machines which steal half the surface area of our cities. At this point, there will be so much more space available for quality housing for all, for parks, for city farms, for life.

We will have long begun to reclaim lawns and parking lots in our cities for people and gardens. We will take back public spaces that had been privatised.

We will begin to feel comfortable around each other in public again because we love each other and we always have. We have always liked meeting new people, so our public spaces will help us do that instead of isolating us in outdated cubicles of individualism.

We will rebuild our cities and redesign our roads for walking, bicycles, and those who move slowly. Public transit will be free, because it doesn’t make sense for it not to be. We will have pedestrian-first towns and cities, the way it always should have been. We will all learn to move more slowly.

The places we live will be aspirational because living a good life was always the point.

We will redefine what we mean by technology.

We do not need more gadgets, we need more connection. We do not need more entertainment, we need more empathy. We do not need virtual reality, we need reality.

The backlash against Big Tech has already begun, and we will continue to hold them accountable for using us as cogs in the wheels of extractive capitalism. We will reject the lie that technology inherently cures loneliness. We will reject technology companies’ efforts to commodify our desire for community.

Midway through this transformational decade, we will begin to realise that what we had been craving all along was a sense of purpose. We wanted to do work that was meaningful. We wanted to belong to something bigger than ourselves.

Through art, music, memes, and methods-yet-to-be-invented, we will laugh and love and interpret what it means to be a part of a thriving global civilisation in the middle of the most transcendent decade in human history.

We will expand our practice of regenerative agriculture. I say “practice” because working in partnership with nature to produce our food is something we knew how to do for thousands of years before we began expanding monoculture agriculture.

The old practice of growing a single crop over large swaths of land had stripped the soil of nutrients, but we will have returned to even more ancient sustainable techniques such as intercropping, where different plants grow side by side, fostering the diversity on which nature thrives. Food produced this way requires less pesticides and fertiliser, allowing for a thriving ecosystem that supports more wildlife.

We will re-learn what we have forgotten. We will build a circular economy.

We will begin decommodifying our own survival; that is, we will provide all the necessities for survival as a human right. We will no longer be "earning" a living or letting how "productive" we are determine our individual importance to society. We will give each other what we deserved all along: acceptance as a fellow living being.

It’s this runaway cycle of production for profit-at-all-costs that created the climate crisis. Stopping this cycle is possible by changing how the economy works. We will abandon the concept of growth for growth’s sake. We will celebrate inefficiency. We will call it creativity. We will call it living.

By establishing a civilisation that values life instead of production, we will recalibrate the economy to care for people and the planet’s needs. Our worth won’t be tied to how much we can produce for people who are already rich. We will build a society that guarantees the basics of survival – food, water, shelter, community – to everyone.

As the decade draws to a close, we will celebrate that our efforts have cut emissions in half globally over the past 10 years. Many countries will reach the goal of zero carbon emissions far sooner than their leaders thought possible. We will finally be on pace for a world without catastrophic climate change. But that will be only a small part of our achievement.

We will have remade what it looks and feels like to be alive. We will have done all this because we had to in order to survive. But, after it is done, we will realise that we did it so that we could thrive.

We will be unable to remember what the old world was like. The key, in hindsight, was understanding that revolutionary change starts with changing how we see how each of us fit into the world.

Perhaps the most radical change of all this decade will be our newfound ability to tell a story – a positive story – about the future and mean it.

What that story looks like will probably be very different than what you’ve just read, but it will feel very much the same. It will feel like something you’ve always wanted, but never thought you’d get. You deserve it.

That is what we have to do now, in the first days of 2020. Dream unashamedly big dreams, dreams that reimagine the more just and loving world we want to live in, not the one traditional science fiction or even the media suggests is inevitable. Put these dreams to paper, speak them into the world, and work together to make them a reality.

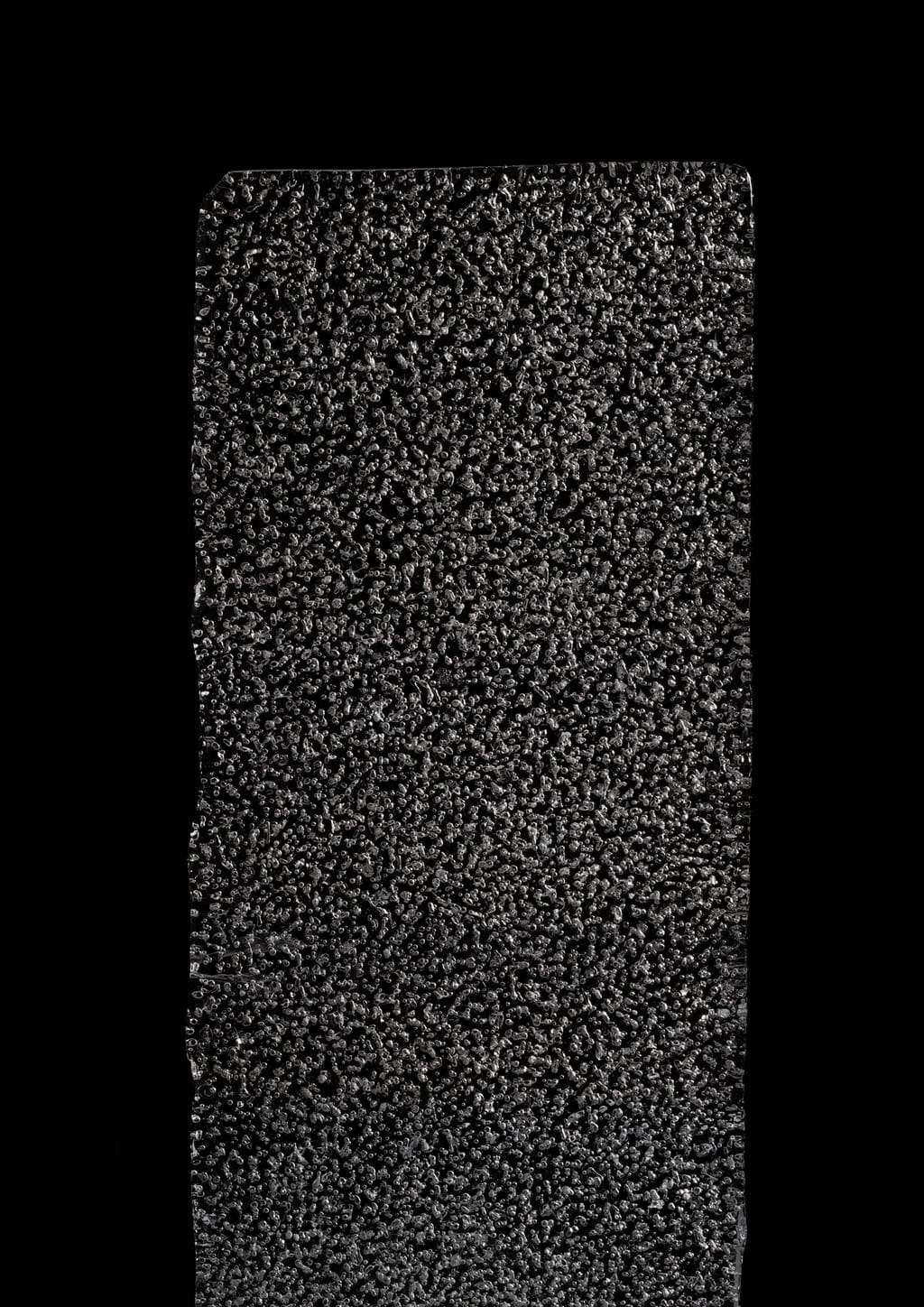

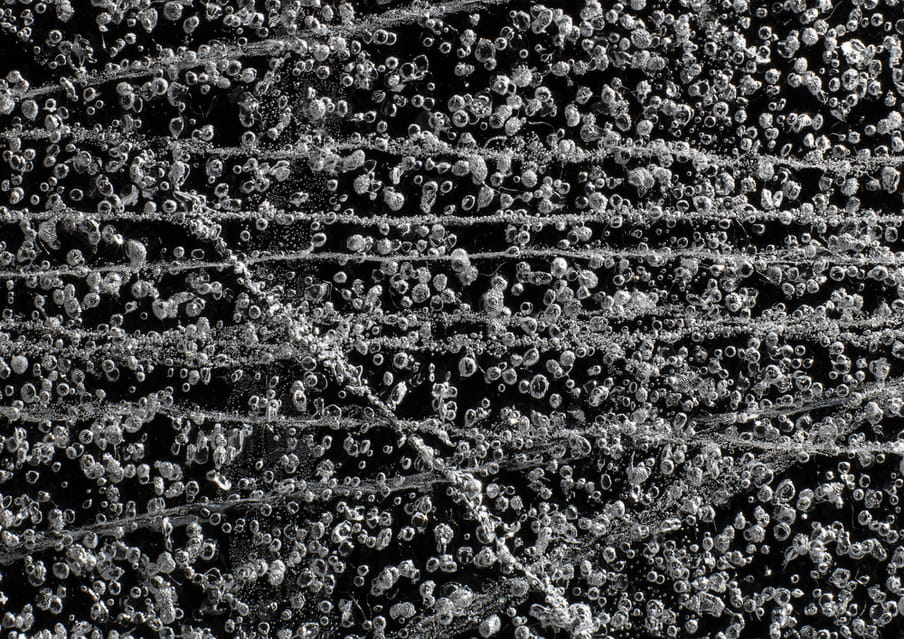

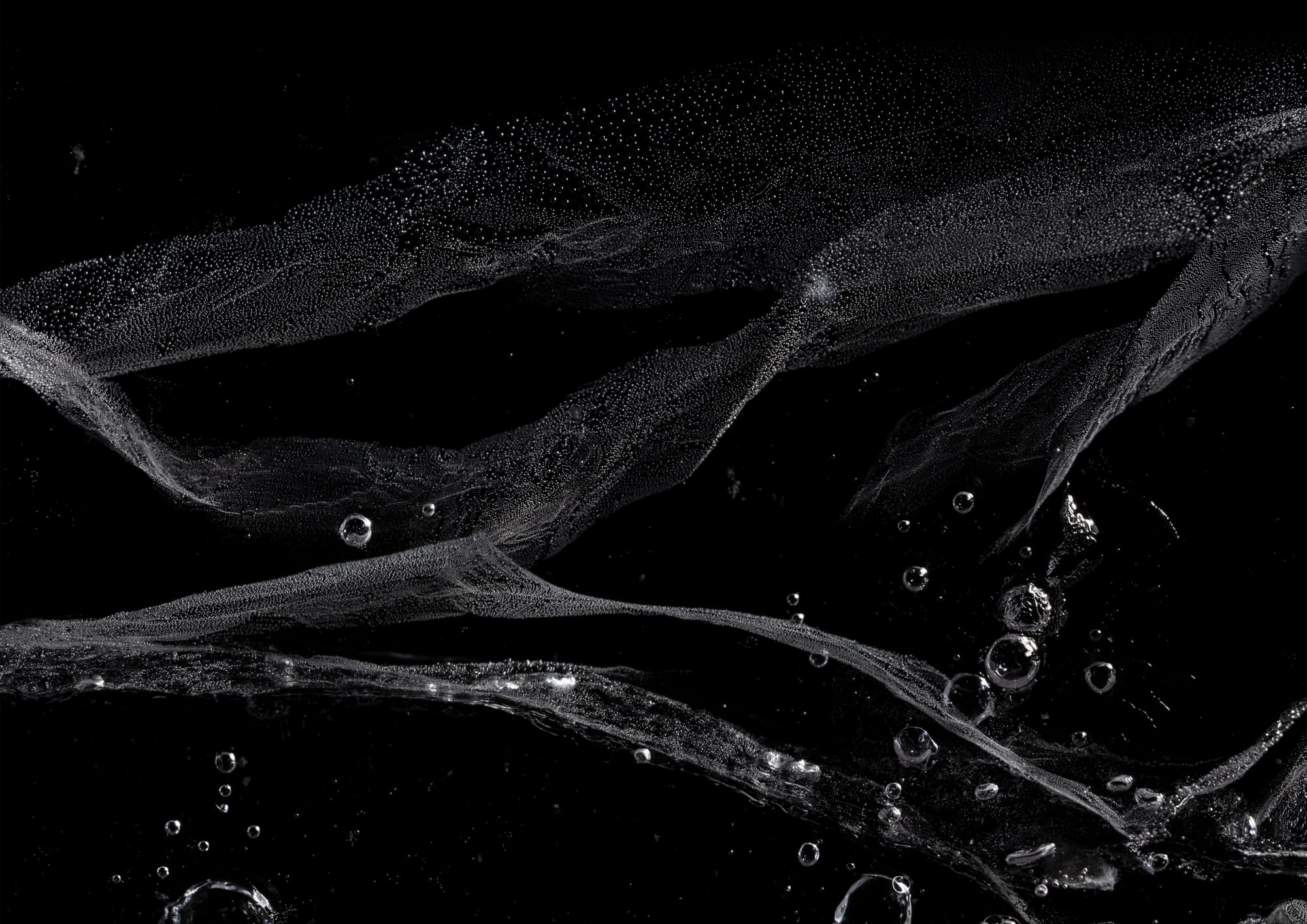

About the images

For the project Climate Archive, photographer Suzette Bousema, whose work usually focuses on climate change, collaborated with scientist Peter Kuipers Munneke. Her photos show ice cores that were extracted in 1995 in Antarctica and Greenland that are about 20,000 years old. They are being used to research the history of our climate. These sheets of ice were formed by snowfall and reveal information about Earth’s atmosphere and climate at the time in their air bubbles and dust particles. The title of the series refers to the idea that the ice caps are an archive in themselves. They store useful information on our climate and contain knowledge from the past that will improve predictions of the future. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

For the project Climate Archive, photographer Suzette Bousema, whose work usually focuses on climate change, collaborated with scientist Peter Kuipers Munneke. Her photos show ice cores that were extracted in 1995 in Antarctica and Greenland that are about 20,000 years old. They are being used to research the history of our climate. These sheets of ice were formed by snowfall and reveal information about Earth’s atmosphere and climate at the time in their air bubbles and dust particles. The title of the series refers to the idea that the ice caps are an archive in themselves. They store useful information on our climate and contain knowledge from the past that will improve predictions of the future. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Dig deeper

Climate change is about how we treat each other

Our weather has changed so rapidly that we now stand on the brink of collapse. But simply speaking about the impending apocalypse will do nothing to change it. We need to reimagine human relationships.

Climate change is about how we treat each other

Our weather has changed so rapidly that we now stand on the brink of collapse. But simply speaking about the impending apocalypse will do nothing to change it. We need to reimagine human relationships.