Almost 20 years ago, at the Lomé seaport, a young man named Justine climbed into the hull of a ship. He strapped starchy food and a small amount of water to his body, and after making his way to the ship’s engine room, he buried himself as close to its warmth as he could. 32 days later, he climbed out into the darkness of a strange port, and tried to establish where his voyage had taken him. It took him four hours to find out where he was: Brazil.

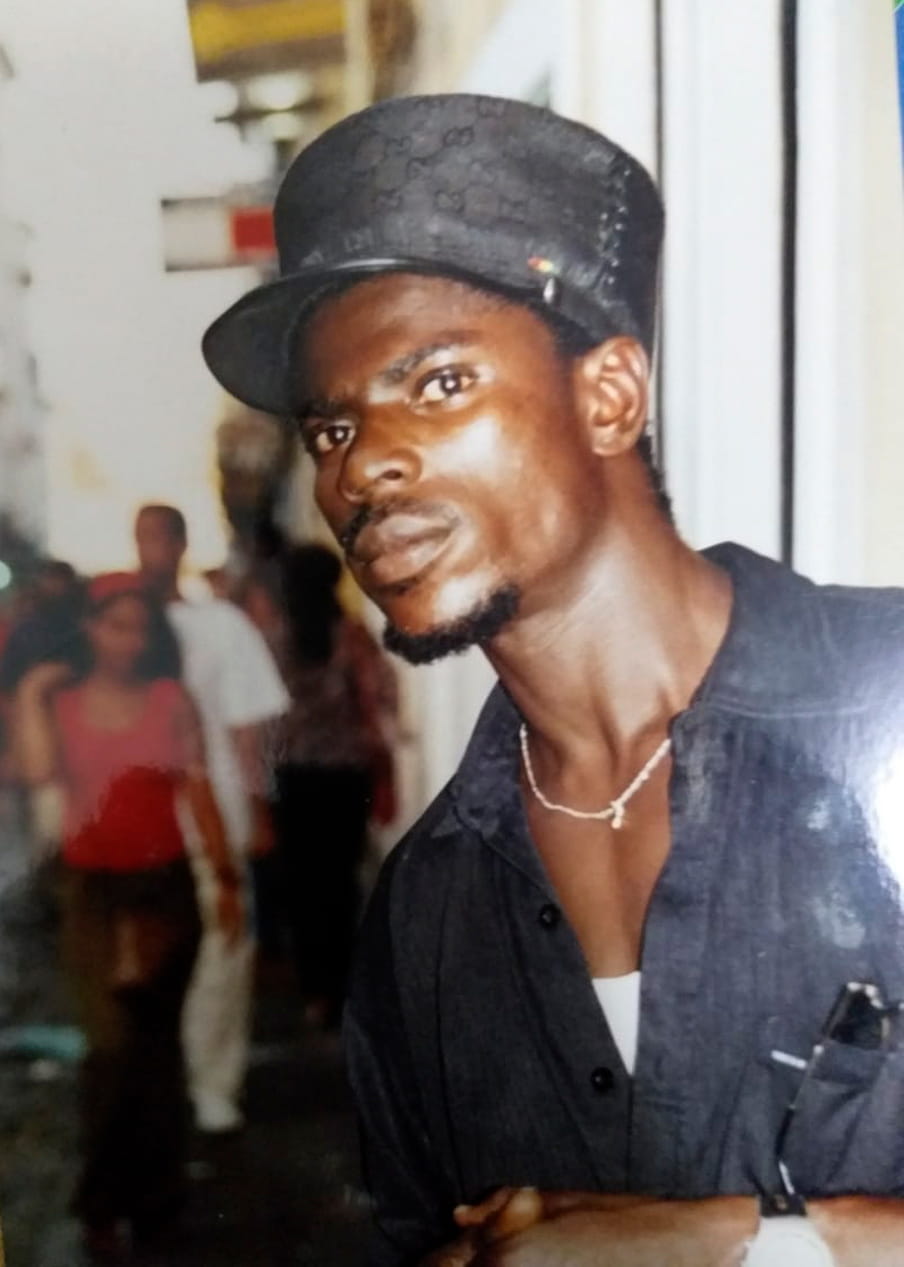

Justine Ankai-MacAdoo, who now goes by DJ Sankofa, had stowed away several times before eventually settling in Latin America’s largest country. On his previous voyages hidden on cargo vessels, he had made his way to Portugal, the Philippines, and South Africa, though he didn’t always know at the start where he would end up.

I met Sankofa completely by chance in 2016. My roommate at a conference in Bahia had spent months arranging to interview him, and I was invited to have lunch with them at his home on my last day in Salvador. I don’t remember what he fed us, but it was delicious, surprising, and very enthusiastically prepared.

Recently, I’ve been writing about borders and untimely, violent death as the ultimate result of social norms that dehumanise people. When I remembered Sankofa’s story, I thought he’d be an excellent person to speak to, to try to understand why someone would circumvent established immigration processes, even at the risk of death. Perhaps Sankofa’s life could teach us something about undocumented travellers – too often faceless and nameless – and about what it is to fully and freely live.

As well as DJing, Sankofa currently works as a travel guide and personal chef. When I catch up with him, he’s in Rio de Janeiro for two weeks, cooking for a client. During our call, he takes several breaks to go into the kitchen. Even over the phone, he’s as vivacious as I imagine anyone who has stared death in the face to be.

In the 1990s, when he was still attempting to arrive at a life different from the one he was born into, the possibility of being killed was part and parcel of what it meant to stowaway. He says the word with easy familiarity, two syllables lilting upwards: “sto-WAY”. The lightness of his tone completely belies the immense hardship the word describes, and the very real dangers faced if caught. “The sailors on board [kill stowaways], because they can’t take them to the shore,” Sankofa says, matter of factly. “If they take them to the shore, the ship will have problems. So the best thing is to dismiss them on the ocean, like what they did in the slave time.”

Despite knowing the risks – and having faced them more than once himself – Sankofa is philosophical: “We have all kinds of travelling, right?” he asks rhetorically. “We have people that travel for quick money. We have people that travel for a better life and we have people that travel just for adventure. My way of travelling, it’s more of using adventure to look for a better life.”

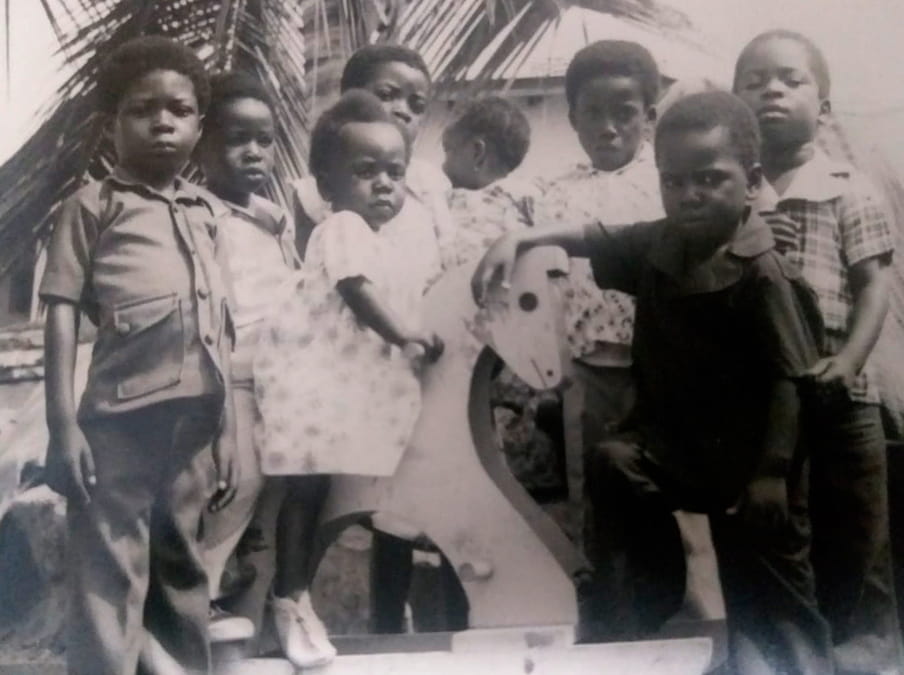

Born in Cape Coast, Ghana, Justine’s parents had several children across multiple relationships. “We’re from the ocean, from the sea; fishermen. But my father wanted us to go to school.” But Justine didn’t take to formal education, and there simply wasn’t enough money to invest in helping him improve his performance.

At the same time, the young people around him spent their days dreaming about getting away. “We were hearing these stories of stowaway trying to travel outside the country without paying no ticket or passport. When you get there, they say the white people take care of you.”

‘We have people that travel for a better life and we have people that travel just for adventure. My way of travelling, it’s more of using adventure to look for a better life.’

“So when I can’t take things anymore in my adolescence, because my dad don’t have no money, we always be hungry, always borrowing things from the neighbours to pay later … I look at that life and I say, what the fuck is this? How long am I going to be in this? And I look around my city, I look around my neighbourhood. I have to be a fisherman. Or, I guess be a hustler.”

Hustling meant taking odd jobs all over southern Ghana, working in a timber market, then as a security guard. Still eager to try for a different life than the one looming before him, Sankofa left for Togo in 1993, taking a bus to the Aflao border and walking, pockets empty, all the way to the ports in Lomé. “Togo is close to Ghana [and] there are many things that are easier. When they arrest you for going to the ship to stowaway, man, for them you’re a king. But in Ghana, you go to jail.”

At the seaport, he survived by teaming up with other young men from across west Africa, all of whom had their gazes fixed on the horizon, certain that a rewarding life was somewhere beyond it. While he gleaned the rules of stowing away, he earned a living by learning the port city’s pleasure spots and directing sailors to them. Being useful to the sailors made it easier to try to figure out which ships left for where, and when.

Weeks after he arrived in Lomé, the novice stowaway made his first attempt, hiding with two other boys on a ship headed to Durban, South Africa. Three days into the trip, they got caught. Once in Durban, the crew handed them over to South African immigration services, and when their attempt to pose as Liberian asylum seekers failed, they were deported back to Togo – at the shipping company’s expense.

After that experience, Sankofa decided to try again, this time on his own. In the next two years, he stowed away four or five more times, sometimes making it to port, sometimes not. Aboard, he would deliberately allow himself to become constipated and dehydrated so the smell of bodily fluids and excrement wouldn’t risk giving him away.

He got caught again, on this, his second attempt. Expecting that the current would carry him to shore, the ship’s crew cast him overboard in a raft, giving him some food they hoped would tide him over. But the winds weren’t in his favour. Instead he floated on the ocean until the same crew found him, days later, on their way back. The sailors pulled him back onboard and took him back to Togo.

By the time Sankofa got his first passport in 2002, he had attempted entry into some eight countries. Over the course of his travels he picked up more than a dozen languages, which now bleed into one another. He starts a sentence in Pidgin and ends it in Yoruba, which he is delighted to use with me.

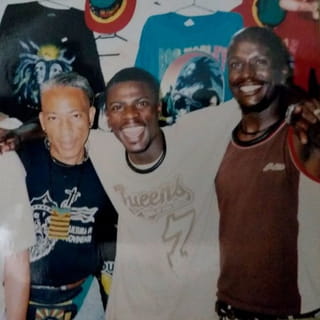

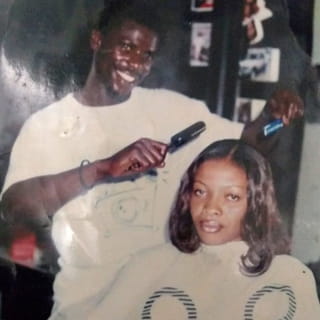

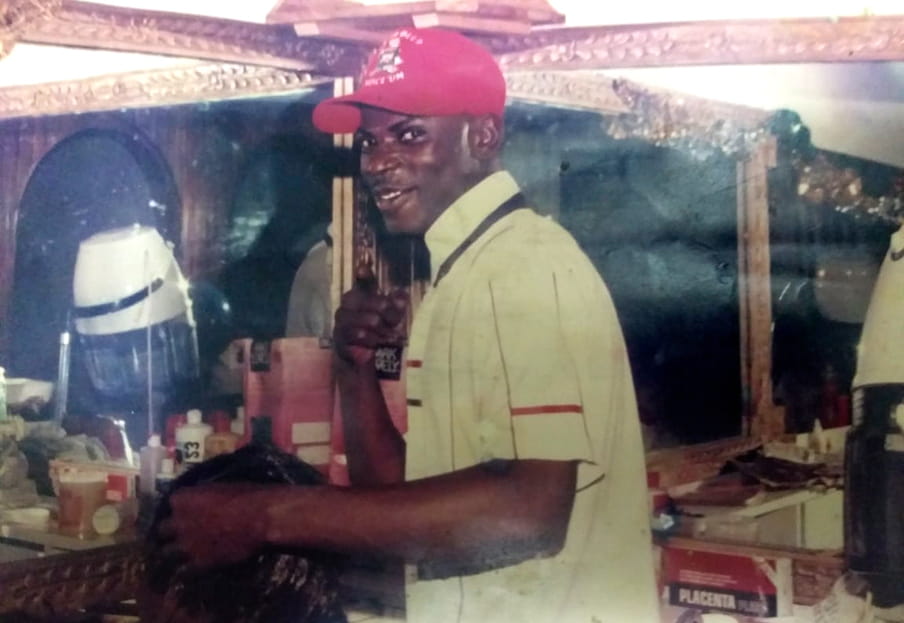

He picked up Yoruba from a five-year stint in Nigeria , a destination he got through via Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon. There, he made a living, and a name for himself, in the beauty industry. He tells stories of establishing salons in Lagos and Abuja, Nollywood stars popping into one of salons he opened, Men’s World, for a haircut but also because it was a great place to be seen. But then, in 2000, Sankofa packs up all of his tools, and heads back to Cape Coast. He gives all he’d amassed to his sisters before heading back to Cotonou’s ports.

“Back home, maybe you have a better life when you have money,” Sankofa tells me when I ask why he went back to stowing away – to risking his life – despite the success he’d found in Nigeria. “But a better life is not really money. It is peace.”

There is a lull in our conversation; kitchen noises pick up in the background. I listen to the sounds, thinking about all of the lives that Sankofa has lived before finding this one. There are people who are comfortable with what they are handed by the circumstances of their birth, but there are many who must try on different options until they find one that fits them as snugly as a life should fit a person.

‘Back home, maybe you have a better life when you have money. But a better life is not really money. It’s peace.’

Sankofa in Twi means "go back and get it". Justine took on the name two years after he arrived in Brazil – his last voyage as a stowaway. The name is emblematic of the work he now also does to connect Afro-Brazilians to their African heritage, in part, through music. In 2001, he noticed that hardly anyone played or even knew anything about African music, despite the fact that Brazil has the largest population of black people outside of the continent. That disconnect represented an opportunity. “There was Afro-Brazilian music, like Olodun, Ile Aiye and others from diaspora Black communities. But they didn’t know African artists, they didn’t have no clue.” He started asking people coming to Salvador to bring him CDs of the hottest sounds from the continent.

“I started improvising with Afrobeat, juju music, highlife from Ghana, Igbo high life, soukous, Magic System, Awilo Logomba … There was one guy, from Ivory Coast. He was here from France with some turntables. So when he was leaving he sold them to me. That’s how I started calling myself DJ.”

As his reputation grew, a Spanish friend who knew he was undocumented advised him to get a passport, and gave him the transport fare to get to the Ghanaian Consulate. “I used the bus for three or four days from Salvador to Brasilia to go and do the passport. Then I went to Policia Federal for them to bill me my ticket for overstaying. It was like $200 that time, about 800 reals.”

For the first time in his life, Justine Ankai-MacAdoo existed on paper. But being in a country legally doesn’t mean you’re welcomed. “I have three different kinds of discrimination, just being African and being black and also [wearing my hair in] dreadlocks. In Africa we don’t see this kind of racism. So it’s strange. That is the most difficult part to absorb.”

“I will not lie to you,” he continues. “Brazil is a very receptive country. I mean, I’ve been living here 18 years. I don’t feel like going back. You leave your mama house and you go to work. You can’t be absorbing every pain, you have to be strong. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen. It happens. You just ignore it so that you can find a better place. I choose to live here. I’ve found my place. This is the happiest, most comfortable and easiest [time] in my life. This moment that you are interviewing me.”

DJ Sankofa has a wife and a teenage daughter. I wonder if he’s ever told her what it was like to huddle as close to the engine of a ship as possible, just stay hidden and keep warm. Does she know that she would not exist if her father had not stolen leftovers from kitchen bins to survive aboard the ship? Perhaps his wife has heard the story many more times than she can count, of the time he was stuck on a raft, at risk of dying of thirst and exposure.

In a migrant-wary world, only certain kinds of people are allowed to travel wherever they want, just because they want to. For those who don’t have the advantage of the right citizenship or class status, for whom the categories of "tourists", "aliens of extraordinary ability" , or "expats" may apply, the world is often on the other side of a locked door to which they have no keys. If they want to get out of where they are, and into anywhere else, a broken window or even a gap in the floorboards will have to suffice.

In a migrant-wary world, only certain kinds of people are allowed to travel wherever they want, just because they want to.

Justine Ankai-MacAdoo found his window in the darkness of ships’ hulls. But people like him are lucky to be alive; lucky to survive the contemporary delegitimisation of their desire to find prosperity and peace wherever they can.

He puts me on hold briefly to return to his stew. When he comes back on the line he says: “I call this grass to grace. When I came to Brazil, I didn’t even have a passport. Now, I use two passports.”

“You know, I went [back] to South Africa – to Cape Town – as a tourist. That’s how I feel like going now, knowing more countries, having the opportunity as a traveller, not as a stowaway.” He laughs. It’s a sudden burst of sound, full of heart. Irresistible. “I never really had documents, I always lived without them … Now I travel [freely]. I can go anywhere I want.”