What’s in a name?

Not far from where my brother lives in north London’s East Finchley neighbourhood is a street called Kitchener Road. I had spotted it by chance: a newish sign of black letters printed on a white metal sheet and affixed to a lamp post. Just behind the lamp post, screwed into the brickwork above a Turkish cafe, was a much older sign, made of thick iron, bearing the same name.

To name a street after a person is a universally accepted way of publicly honouring that person’s achievements. The two signs on Kitchener Road, one old and one new, seem a clear indication that this individual has once been honoured and is still deserving of public recognition.

Street names help us figure out where we are, talk about where we’ve been, and ascertain whether we’re heading in the right direction. This is of course true both literally and figuratively. Names such as 125th Street or West Side Highway are purely descriptive; they express the geographical location of the thoroughfare. But more often than not, streets take their names from people, places, events or things, in these instances situating us not only geographically but also politically, socially, historically. As such, Kitchener Road reminded me of Britain’s long and brutal history of colonial domination.

To say that street names are a physical marker of history is to invite two critiques. The first is that this is all much ado about nothing; that street names don’t really matter. The second is that any calls to change these names is to “erase history”, an erasure which – to those who argue this point – is as bad as the acts the signs commemorate. Perhaps we should consider the evidence.

Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) was a notoriously brutal military officer of the British Empire, working across Palestine, Egypt, Sudan, South Africa, and India. During the second Anglo-Boer War, Lord Kitchener, who took over the war effort in 1900, innovated a three-fold strategy that included burning homesteads to the ground and keeping large numbers of people – both black and white – in concentration camps. 48,000 people are recorded to have died in these camps.

The commemoration through street names of people who have been responsible for killing, dehumanising and exploiting others is a powerful way to preserve a celebratory view of colonial history

The Irish-born, Swiss-educated soldier, who was also known as Earl Kitchener of Khartoum, is more fondly remembered for his role in annihilating anticolonial forces in Sudan, killing tens of thousands at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898. He celebrated his victory by dynamiting the tomb of the revered religious leader Muhammad Ahmad (known as the Mahdi). Kitchener had the Mahdi’s bones thrown into the Nile. British prime minister, Winston Churchill, who as a young officer had been a part of the same campaign, wrote in his book, My Early Life, that Kitchener “had carried off the Mahdi’s head in a kerosene can as a trophy”. This is the man whose name has been endlessly imprinted across the map of modern Britain. In London alone, there are at least five different residential Kitchener Roads.

Britain is not alone in these acts of commemoration that casually sidestep the brutal reality of many of the people honoured in this way. In Belgium you will find many streets, such as Boulevard Leopold II, named for the Belgian king who personally owned the Congo Free State (1885-1908) and was responsible for the deaths of up to 15 million people while accruing vast wealth through the production of rubber.

Unlike King Leopold II, Kitchener’s face is as well known in Britain as his name. An illustration for the London Opinion magazine of his glowering, pointing, thickly mustachioed face and pointed finger, demanding men to enlist during the first world war has become one of the best-known recruitment posters. This image is freely reproduced within the iconography of British colonial nostalgia (a booming industry), and Kitchener remains the embodiment of jingoistic masculinity.

In fact, Kitchener has been so deeply embedded in British cultural memory that his name makes an appearance in the most unlikely of places. Knitters may choose to use the Kitchener Stitch, which I am told is the optimal way to graft or join stitches, particularly at the toe of a sock. Apparently Kitchener insisted on this stitch in order to reduce chafing, and therefore the risk of trench foot, among his troops.

One person who understood perfectly well the powerful significance of streets and naming practices was Kitchener himself. Drawing up plans for Sudan’s capital city, Khartoum, in 1898, he named a central thoroughfare Victoria Avenue in honour of his queen. Not only that, but Kitchener instructed officials to design a grid pattern for Khartoum’s streets that was arranged in a Union Jack pattern that reproduced unmistakably the triangular shapes of the British flag. That crude piece of imperialist urban planning survives in Khartoum today.

Rewriting the past, reshaping the present

The commemoration through street names of people who have been responsible for killing, dehumanising and exploiting others is a powerful way to preserve a celebratory view of colonial history, and normalises this narrative in everyday life. So how should it be addressed?

My own view is that such signs should simply be torn down and the streets renamed. This is what happened in Mozambique from 1975, when the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (Frelimo) came to power having fought Portugal’s fascist colonial government in the war of independence.

When I lived in Maputo, I stayed on Avenida Vladimir Lenine and attended Portuguese classes on Avenida Karl Marx. I bought groceries on Avenida Kwame Nkrumah and would sometimes enjoy a coffee at a place on Avenida Patrice Lumumba. In this way, a city spells out a set of commitments. This is as true in London, where Kitchener and other colonial “heroes” are still memorialised, as it is in Maputo, where the old colonial street names have simply been disposed of, and replaced with the names of the kinds of left-wing radicals and revolutionaries whose struggles and ideas grounded hopes for a free and socialist future in the new People’s Republic of Mozambique.

If simply doing away with problematic names is not to your taste, another possibility is to follow this example spotted in Amsterdam. In the Dutch capital you can find Albert Luthulistraat (honouring the great anti-apartheid leader of the African National Congress). Beneath the Luthulistraat sign, details of the previous honoree are provided: "Formerly: Louis Botha street." Botha was the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa, a forerunner of apartheid South Africa. This renaming models a practice of redress that preemptively avoids accusations of erasure.

In rare cases, a colonial street name survives for locally specific, often amusing reasons. Napier Road in the city of Karachi is named after Charles Napier, the first British Governor of Sindh – now Pakistan. It also happens to be the site of the city’s red light district. “Following independence, many streets named after colonial Britishers were renamed after illustrious Pakistanis,” Mahr Malik told me. “But I suppose no Pakistani government officials wanted a Pakistani name on this one.”

In places where colonial street names persist, there has, in recent years, been an upsurge in local people organising walking tours that put those names into fuller context. In Scotland, the Coalition for Racial Equality and Rights ran a walking tour of Glasgow for Black History Month this year, with the purpose of illuminating “the reality of Glasgow’s role in the enslavement of human beings”.

There are now similar walking tours in several Dutch cities, as well as in New York. Such projects are creative, imaginative responses to painful and damaging histories, and at their best they work constructively to build thoughtful and collective ways forward at the local level. ‘Colonial Traces in my Neighbourhood’, for example, provides school pupils with classes on everyday colonial traces and facilitates interviews with elderly people living in their neighbourhood who grew up in the former Dutch colonies.

Another noteworthy approach to mapping such histories is University College London’s groundbreaking project Legacies of British Slave-ownership, which includes not only a database of British slave-owners (based on 19th-century public records) but also provides users with an interactive map that pinpoints the addresses of slave owners on many of the very streets we walk today.

Continuing on to my brother’s, I turned off Kitchener Road and thought of a very different Kitchener: the legendary Trinidadian calypso musician Aldwyn Roberts, who performed to huge acclaim under the stage name of Lord Kitchener. This Kitchener come to England from Jamaica aboard the Empire Windrush in 1948, the vast passenger ship whose arrival has often been used by historians as a marker inaugurating modern, multicultural, postcolonial Britain.

As he disembarked the vessel at Tilbury port, Lord Kitchener spontaneously performed London is the Place for Me, a song he had written aboard the ship to mark the occasion of his arrival. The song asserts his ownership over the metropolitan centre of the British Empire, just as he had audaciously claimed the title of one of Britain’s most celebrated imperialists as his own.

I thought about the song’s opening lines as I walked:

London is the place for me

London this lovely city

You can go to France or America,

India, Asia or Australia

But you must come back to London city

Well believe me I am speaking broadmindedly

I am glad to know my mother country

I have been travelling to countries years ago

But this is the place I wanted to know

London that is the place for me.

If the many Kitchener Roads are to keep their name, rather than commemorating a colonial butcher, I’d like to imagine them as honouring the “King of Calypso” instead.

Thank you for reader contributions to Moos van Caspel, Minka Bos, Kira van den Ende, Ceecy Nucker, and Mahr Malik.

About the images

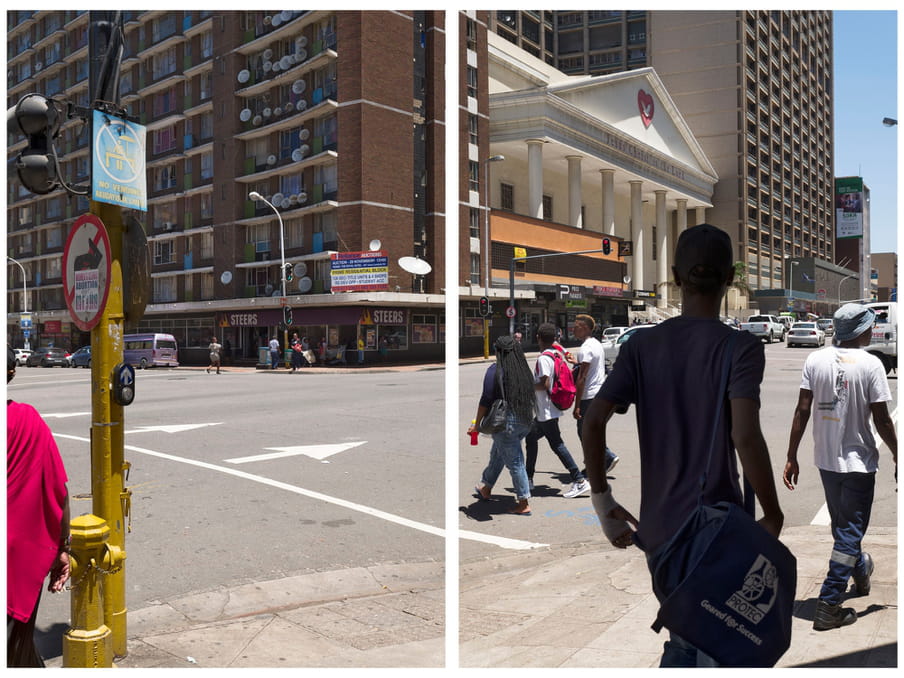

South African photographer Guy Tillim was orginally attracted to the medium for its ability to document and confront the racial gap in his country. Nowadays his work reflects on the postcolonial realities of nations in Africa. For his series Museum of the Revolution, Tillim travelled across Africa to find cities in which streets had been renamed following decolonialisation. Following the tradition of street photography but reimagining it in his own way, Tillim reflects on the celebration of independence by changing the narrative of these places. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

South African photographer Guy Tillim was orginally attracted to the medium for its ability to document and confront the racial gap in his country. Nowadays his work reflects on the postcolonial realities of nations in Africa. For his series Museum of the Revolution, Tillim travelled across Africa to find cities in which streets had been renamed following decolonialisation. Following the tradition of street photography but reimagining it in his own way, Tillim reflects on the celebration of independence by changing the narrative of these places. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Dig deeper

What do we do with our colonial relics?

Consider the pith helmet, a symbol of exploration and expansion – and a fashion accessory worn by Melania Trump. Does it still carry meaning or is it old hat?

What do we do with our colonial relics?

Consider the pith helmet, a symbol of exploration and expansion – and a fashion accessory worn by Melania Trump. Does it still carry meaning or is it old hat?