Hi,

Let’s talk business today. Allow me to introduce to you three startups from three different corners of the world, which together represent the unique opportunities and challenges for businesses eyeing a massive market: broken human minds.

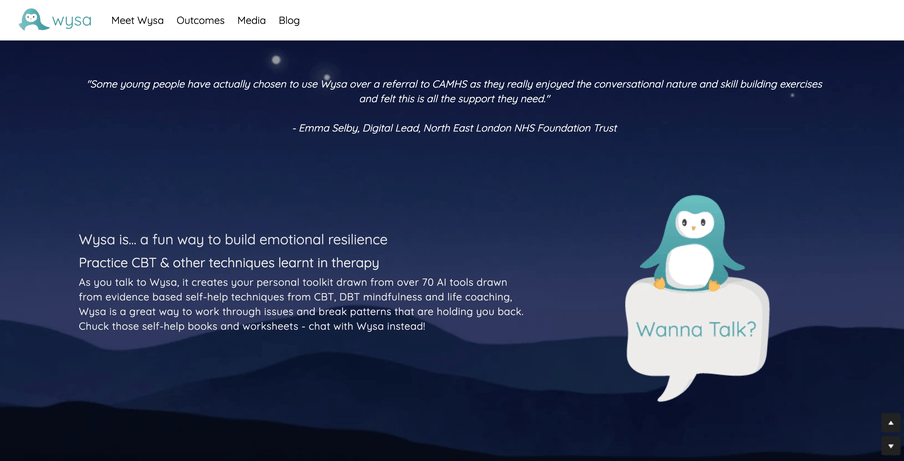

First, meet Wysa, a mental health app built in Bengaluru, India. Founded barely four years ago by the wife and husband duo of Jo Aggarwal and Ramakant Vempati, Wysa has garnered over a million users across the world (I am one of them), to whom it offers a combination of free artificial intelligence-based chat support and paid human coaches. Wysa was chosen for the first-ever Apple Entrepreneur Camp that ended on 23 October.

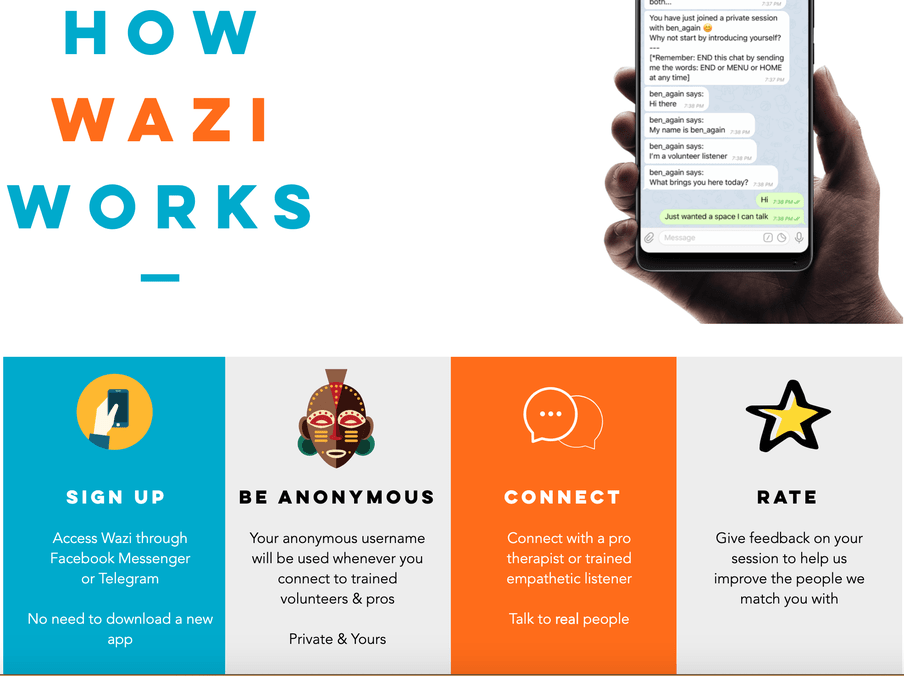

Next, say hello to Nairobi-headquartered Wazi, launched last year. I discovered Wazi via a LinkedIn notification last week that Alex Royea, co-founder and CEO of the company, had started following me. Wazi’s website says it is an "anonymous digital therapy" platform that can be accessed via Facebook Messenger or Telegram. (I have emailed Royea requesting an interview but haven’t yet heard from him.)

Finally, there’s Two Chairs Therapy, founded two years ago in San Francisco by Alex Katz. Two Chairs Therapy is different from Wysa and Wazi in that it uses technology to find the right match between users and mental health professionals - but its USP lies in its chain of brick-and-mortar clinics. In August, Katz announced that the company has raised US$21 million in a Series B funding round.

The "tech" prefix is valuable in the startup world for one reason: scale. It is the magical bridge between cool ideas and constituencies that might otherwise remain unreachable. It is the salt without which startups are deemed unappetising for growth- and returns-hungry investors. Solving for mental illnesses, a multitrillion-dollar global challenge, is, naturally, a salivating prospect for entrepreneurs and the moneybags backing them.

"[T]he amount of venture capital money deployed in mental health tech deals is projected to almost triple in 2018 compared to last year (2018F: $793m, up from $322m in 2017)," writes Edouard Gaussen, CEO and founder of the New York-based mental health company Mantra Health.

Of course, the problem with the human mind is that it frustrates business models that are a rage in the rest of the tech-startup universe. You can’t grow a great mental-health business by building giant marketplaces or last-mile delivery hacks, or by throwing irresistible discounts at customers who don’t care where they buy from as long as it’s cheap.

Different companies are taking different approaches to counter this. Wysa claims that its AI-based intervention takes away the stigma that comes with seeking in-person help by facilitating anonymous conversations with a cutesy chatbot. It guarantees user privacy - a prickly subject in all of health-tech - by requiring no logins, and enhances the accessibility and affordability of services by removing the dependence on expensive physical spaces. The bot (hopefully) can become the first step in a user’s journey to accepting help.

But within the entrepreneurial community, there’s a deep divide about this claim. Richa Singh, founder of the online therapy platform YourDost in India, had once told me that she sees tech as only an enabler, not a replacement for humans. For people like her, the idea that mentally ill people will somehow start buddying up with bots is absurd.

Wysa, and a similar American platform called Woebot, have also dealt with criticism about the ability of their algorithms to respond sensitively to potentially serious cries for help, though both have since overhauled their platforms and added fresh safeguards.

This is connected with the larger problem of the absence of a strong regulatory regime for mental health apps . Soumitra Pathare, an Indian psychiatrist who played a key role in shaping India’s Mental Healthcare Act, 2017, has repeatedly raised questions about allowing such apps in the market without rigorous checks, such as clinical trials, which are mandatory for drugs. On its part, Wysa says it has been given a 93% score by Orcha, an organisation that evaluates the safety and efficacy of care and health applications.

Increasingly, the zeitgeist seems to be moving towards limiting tech to the role I described above: a connector between demand and supply. Two Chairs Therapy is a good example of this philosophy at work. "Technology at Two Chairs means building products and experiences that improve in-person care — not replace it," writes founder Katz.

It remains to be seen if brick-and-mortar therapy chains can raise enough capital to become viable in fledgling markets such as India and Kenya. Among other things, this depends on finding the right price that people are willing to pay for mental health care. Corporate clients paying for "wellness" programmes could be a handy revenue source, but Royea of Wazi writes on LinkedIn that in 2017, in Sub-Saharan Africa, only US$0.3 billion total was spent on corporate wellness, compared with US$17 billion spent in the US alone.

There’s a steeper hurdle still - the extremely shallow supply of trained therapists in these developing markets. According to one study, Kenya, for instance, has only about 88 trained, working psychiatrists. Only 16 out of 47 counties have psychiatrists in the public sector, and none have psychologists.

How do you see technology’s hand shaping the mental health landscape? Any smart companies in your part of the world that you’d like to tell me about? I’m listening.

Cheers,

Tanmoy