In this time of disruption, confusion, and cynicism, few professions or institutions command the public’s trust and respect. But thanks in part to Hollywood, investigative journalists still count as the good guys. There’s a Wolf of Wall Street but not Fleet Street.

So it’s with some reluctance that I raise the following question: As demagogues and protest parties launch a full-scale attack on representative democracy, are investigative journalists at risk of becoming their useful idiots?

Those old enough will remember that the derogatory term “useful idiot” comes from the Cold War. It described individuals in the West whose actions aided the Soviet cause, even if they had no communist sympathies themselves and were unaware of the consequences of their actions.

The peace movement in Western Europe in the 1980s is a prime example: Pacifists may have believed they were furthering the cause of peace by opposing nuclear weapons. For the Soviets they were ignorant pawns that could be used to undermine the unity of the West, oblivious as they were to the Kremlin’s cold war games with Western governments.

Is investigative journalism now at risk of providing ammunition for the enemies of democracy as we know it? Are we their unwitting pawns, their useful idiots?

Austria, Nationalrat. From the series Parliaments of the European Union, by Nico Bick.

Watergate and a “self-cleaning” democracy

The archetype of successful investigative journalism is of course Watergate. Reporters at The Washington Post revealed President Nixon’s involvement in illegal espionage – a break-in and bugging of the Democratic Headquarters – as well as the subsequent coverup. Nixon resigns in shame and the journalists receive the 1973 Pulitzer Prize. Reporters Woodward and Bernstein become world famous when Hollywood immortalizes their adventures in All the President’s Men.

That’s the ideal version of journalism as a check on power. Revelations that the president has broken the law shake the trust and faith of every sane citizen in the country. When the ensuing scandal leads to the president’s resignation, trust is not only restored, it’s enhanced. For if even the country’s most powerful man is not above the law, the system clearly works. Remember that Woodward and Bernstein’s Pulitzer was awarded in the “Public Service” category.

Some call this mechanism democracy’s “self-correcting” property. The Dutch use the term “self-cleaning” capacity.

Of course there’s a huge gap between theory and practice when it comes to democracy’s self-cleaning capacity. Most revelations of wrongdoing are never followed up on. The Watergate investigations by The Washington Post and also by Time and The New York Times were initially ignored, mocked, or downplayed by other media outlets. Taken together they were only one element in a larger political process that eventually brought Nixon down.

But the underlying principle is clear: investigative journalists help uncover the abuse of power and keep that story going for long enough to force the rest of the system to respond. In its optimal form a democracy is what the philosopher Nassim Nicolas Taleb calls “antifragile.” A shock to the system, in this case exposing abuse of power at the top, ends up making that system not weaker but stronger.

Watergate happened in the early 70s. We’re now in a very different place. Politics has undergone fundamental changes, with important if deeply uncomfortable consequences for the practice of investigative journalism.

Today the stakes are higher than ever

In the Netherlands where I live and work, and at the national level across Europe, we’re witnessing the implosion of the two traditional political blocks: a large, stable block on the left, made up of social-democratic or socialist parties; and a right-of-center block on the other side, with Christian-democratic or republican parties.

Until the 1990s, most European countries had a ruling party and one major opposition party. What journalists managed to dig up fed into that oppositional dynamic. Simply put: the opposition could run with our stories. And since that opposition constituted a clearly defined and consistent challenge to the governing party come election time, the latter was likely to be forced to respond.

Investigative journalism presumes a bona fide opposition. An alarming number of countries now fail that test

Of great importance here is that the opposition was earnest. Even more crucially, it was constructive. The opposition had its own realistic agenda to pursue and could use journalism’s revelations as a tool of shame. If that didn’t work, voters could punish the governing party in the next elections.

Now suppose that instead of a serious and constructive Democratic party during Watergate, the main opposition to Nixon had been led by someone like Donald Trump or Boris Johnson.

That’s now the situation in France, for example, where any devastating revelation that would lead President Macron to resign would likely bring to power Le Front National, France’s right-wing nationalist party. In Germany a Watergate-type scandal incriminating both parties in the ruling coalition could lead to the far-right Alternative für Deutschland taking power. The same could be true for the Netherlands, where Geert Wilders is waiting in the wings.

Germany, Deutscher Bundestag. From the series Parliaments of the European Union, by Nico Bick.

Enter the scandal:

To see how this could happen, consider the expenses scandal of 2009 where British MPs were revealed to have abused their expense accounts, often in disgusting, bizarre, or ridiculous ways. The scandal was a feat of investigative reporting. It damaged the reputation of both major political parties, and rightly so.

But when the EU referendum came along a few years later, this loss of trust and standing contributed to the succes with which the clowns, liars, and demagogues of Vote Leave managed to spread their empty promises. The argument here is not that Britain should not have left the EU. It’s free to do so.

My argument is that the British people were lied to on an unprecedented scale, leading millions to vote for a fantasy: that you can stop being a member of the EU while retaining its benefits. That empty promise was sold so successfully in part because those denouncing the fantasy had seen their credibility seriously damaged by the expenses scandal.

Our work as investigative journalists presumes a bona fide opposition that’s earnest and coherent. An alarming number of countries in the democratic West now fail that test.

The new protest parties are literally that: rather than offering an actionable and well-argued alternative for the future, they merely present a platform for legitimate as well as illegitimate frustrations and grievances, defining themselves primarily by what they’re against.

What happens when clowns and vandals get into office? Might our work inadvertently be helping them?

The chaos now engulfing the United States and the political paralysis currently gripping Britain demonstrate what happens when clowns and vandals of this kind get into office. The question for investigative journalists is then: might our work inadvertently be helping them?

In order to answer that question there’s a second level to consider, that of the European Union. The United States of America is mired in its own crisis and problems, some of which overlap with Europe’s. But the US is not involved in a massive transfer of political powers to a higher, continent-wide level in the way EU member states have been for the past decades. For this reason the US and what you might call the American political experience is becoming less relevant to Europeans. Our political systems have simply grown too far apart.

The problem for investigative journalism at the European level is that a democracy’s self-cleaning capacity requires not only a serious opposition committed to the rules of the game. It also requires a functioning political arena.

Where does politics happen?

Where is this political space or public sphere at the EU level? Where are the news programs, papers, magazines, talkshows, websites, and literary reviews? We have a London Review of Books, not only for books but also for top-notch political debate. There’s an equally formidable New York Review of Books.

But there’s no European Review of Books, just as there’s a Times of London but no Times of Europe. Yes, I know we have Euronews and VoxEurope and EUObserver and a few other outlets. Reporters there would be the first to admit that the impact of their work bears no comparison with political coverage at the national level.

As political scientists like to say: Power may now reside at the European level, but politics still happens at the national level. And so news organizations may have one or two people in Brussels, and a dozen or more in the nation’s capital.

What all this means is that after the initial wave of shock and outrage that greets European or EU-related exposés, a political follow-up is even harder to sustain than at the national level. European news organizations are getting better and better at coordinating and synchronizing their scoops, as we saw with the Panama Papers. This works to create a simultaneous wave of interest and outrage. Talk to the NGOs in Brussels fighting tax evasion and they’ll tell you that the press did more to push the issue up the agenda than twenty years of advocacy.

But for the self-cleaning capacity of democracy to work, that wave of interest and outrage is merely the first step. A political follow-up that leads to actual changes is crucial. That’s how shocked citizens know that this particular wrong has been put right. To go back to those NGOs fighting tax evasion: You could argue they’re part of a fledgling opposition at the European level. But how can that opposition work in the absence of a functioning EU political arena, where political pressure could be kept on until real change takes place?

France, Assemblée nationale. From the series Parliaments of the European Union, by Nico Bick.

Outrage isn’t enough

In recent years Investigate Europe – a group of investigative journalists from 9 European countries – has done fantastic work, for example on “Europe’s dire dependency on Microsoft.” They did equally piercing work on Frontex, the EU agency to secure borders. A few headlines: “Why the European Border Regime is dysfunctional,” “How the EU cozied up to the defense lobby,” “Europe plans the surveillance state,” “Mission impossible in the Mediterranean.”

Yet these pieces leave readers in a state of powerless outrage: “How could this be allowed to continue?” If you then go online to look for the political follow-up, more often than not, there isn’t any. Or there was a response but you have no idea of its scope, since you’d first have to understand all the ins and outs of how power at the EU works.

Who could blame you for not knowing the implications? For power at the EU level works in fundamentally different ways than at the national level. The end result? Readers sink back into anger, despair, or apathy.

We’re not responsible for how our political systems developed. But we cannot simply walk away from the political consequences of our work

So there we are. The implosion and fragmentation at the national level undermines the self-cleaning capacity of our democracies. The diffusion of power at the European level does the same. As investigative journalists we’re not responsible for how our political systems developed. But we cannot simply walk away from the political consequences of our work.

I grew up in the 1980s and 90s when the political center was solid. In those days it made sense to be as critical as possible about state power and the governing party. At the moment, the political center is shrinking before our eyes. What worries me is that exposés without meaningful and visible political follow-up end up fueling discontent.

When misdeeds have no political fallout

A number of years ago, I spent over two years investigating the culture of finance in the City of London. What I found was truly shocking. Turns out that when Lehman Brothers collapsed in September 2008, our economies – and hence society at large – had been in a state of near-collapse for months on end. We were unwittingly close to a scenario in which we would have lost access to our bank accounts while the economy ground to a halt and supplies to supermarkets, pharmacies, gas stations would stop. We were 36 hours away from that scenario. That’s how dangerous the mega-banks are.

What I found most disconcerting is the broad consensus among top financial journalists and academics, as well as former central bankers such as Jean Claude Trichet, that our financial system is no safer today than it was in 2008.

The fragility of our financial system is now well documented. But the system has become immune to exposure. What do I mean? To put it in terms of Nixon: Imagine everybody knows that the man is illegally spying on the Democratic headquarters at the Watergate. But no one follows up. And there’s no political fallout whatsoever for the President.

The financial crash of 2008 was the worst since the 1930s and could have been far, far worse. After a crash of this magnitude you would expect wide ranging debates followed by decisive and groundbreaking political action. But while we have endless easy-to-produce stories about banker bonuses, the kind of wide-ranging political campaign necessary to make finance safe again seems further away than ever.

Our financial system is no safer today than it was in 2008, but it’s become immune to exposure

Where does that leave investigative financial journalists? And when will national political journalists join forces with them, building on the work of their financial colleagues to really turn up the heat and push for change?

To give an example: one reason finance hasn’t been fixed is that so many mainstream politicians end up working in the sector. It would make sense to ask political leaders in every future debate: if your party supplies the next minister of finance, can you guarantee that person will never go work in the financial sector?

Ten years after Lehman Brothers, and it seems that’s still too much to ask of political journalists.

But another part of the explanation for finance’s immunity to exposure is that a real change in the DNA of the financial sector must occur at the European or global level. And national journalists don’t work at the European or global level.

Journalists who do, meanwhile, find it exceedingly difficult to keep the story of financial reform going. It can be technical and dull, at least initially. Financial reporting also involves a number of institutions that are technocratic rather than democratic in nature: the European Central Bank, the European Commission, the Court of Justice of the European Union.

Add to this the difficulty of holding national politicians to account for outcomes they’ve negotiated at the European level. To be sure, national politicians are deeply involved in those outcomes. But they’re not ultimately responsible for them except collectively. And there’s no collective European public opinion to hold them to account. Instead national leaders go home to claim victory in Brussels. Or they change the subject.

Greece, Βουλή των Ελλήνων. From the series Parliaments of the European Union, by Nico Bick.

We need sustained reporting on the political consequences

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying we should call off the hunt and stop investigating the failings, crimes, and misdemeanors of those in power.

But I worry about the emails I keep getting from people convinced I’m on their side, their side being people convinced that finance is run by “the Jews,” or the Illuminati, the Bilderberg Group, or whatever theory makes the rounds next on the web.

I worry when my work is held up as proof that democracy’s a sham: “Look how our leaders are in bed with the banks! We need a strongman instead, someone like Putin!” I worry even more when I find my talks exposing the dangers of finance and its entanglement with mainstream political parties on websites right next to crazy conspiracy theories.

Is my work now feeding the hunger for undemocratic leadership with make-believe solutions a la Trump and the Brexit?

Is my work now feeding the hunger for undemocratic leadership with make-believe solutions a la Trump and the Brexit?

As investigative journalists we feel that our work is done when we’ve nailed the story. If we’re lucky we might even collect an award before moving on to document the next instance of government failure or corporate abuse.

But given how radically our democracies are changing, can we stick to merely exposing what’s going wrong? Shouldn’t we insist that the news outlets publishing our work ensure sustained and meaningful reporting on the political response to our revelations? And if there’s no response, to report on that, too? And shouldn’t we find ways for national politics reporters to shed their reluctance and ask politicians the hard questions about their careers in finance?

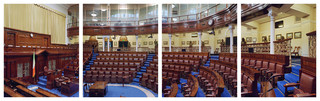

Ireland, Dáil Éireann. From the series Parliaments of the European Union by Nico Bick.

Looking for answers in new places

One might go a step further still and ask if there’s perhaps also investigative journalism to be done about things that are going unusually well? I know, good news bulletins tend to be terrifically boring. But it’s becoming increasingly difficult to deny that in Europe’s current political configuration, our ever-critical work could undermine what’s left of ordinary voters’ trust in democracy.

As investigative journalists we also tend to be quite cynical about politicians. Is that attitude still helpful now that cynicism has been appropriated by the likes of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson?

If only there were some easy answers. What seems beyond doubt is that the EU will never be a functioning democracy if we don’t build a corresponding public sphere. In some respects the EU now mirrors the Arab world, where reliable investigative journalism is extremely rare indeed.

And while Arab countries can’t boast what Europeans have constructed over the past half century – a common currency, a Europe-wide parliament, and a European Court of Justice – the Arab world has something Europe does not: a public sphere spanning the entire Arab world with pan-Arab news sites, newspapers, radio stations, and satellite stations.

So while European leaders may have very little to learn from their Arab counterparts, the opposite is true for journalists.

Maybe it’s time to look south of the Mediterranean for some inspiration.

This is an edited version of the keynote I gave at the 2018 European Investigative Journalism Conference in Mechelen, Belgium.

Parliaments of the European Union

Nico Bick photographed parliamentary chambers in all 28 EU member states between 2010 and 2016. Positioned in a spot on the plenary chamber floor that’s not generally accessible to the public, he made detailed portraits of the vacant interiors. Nico’s work shows how the chambers – despite their similarities – can vary from one country to the next. The architecture, furniture, color choice, lighting, and ornamentation lift the spaces out of the functional and into the realm of cultural representation.

Parliaments of the European Union

Nico Bick photographed parliamentary chambers in all 28 EU member states between 2010 and 2016. Positioned in a spot on the plenary chamber floor that’s not generally accessible to the public, he made detailed portraits of the vacant interiors. Nico’s work shows how the chambers – despite their similarities – can vary from one country to the next. The architecture, furniture, color choice, lighting, and ornamentation lift the spaces out of the functional and into the realm of cultural representation.

Need an antidote to the daily news grind?

Sign up for our updates. Find out what we're doing to make a full English edition of De Correspondent a reality. And how you can help.

Need an antidote to the daily news grind?

Sign up for our updates. Find out what we're doing to make a full English edition of De Correspondent a reality. And how you can help.

More from De Correspondent:

This is how we can fight Donald Trump’s attack on democracy

The news provokes outrage every day, but it rarely inspires sustained resistance. Now that Donald Trump has launched a frontal assault on democracy, the press needs to fundamentally change tack. Journalists have to beat historians to the punch and write history – before it repeats itself.

This is how we can fight Donald Trump’s attack on democracy

The news provokes outrage every day, but it rarely inspires sustained resistance. Now that Donald Trump has launched a frontal assault on democracy, the press needs to fundamentally change tack. Journalists have to beat historians to the punch and write history – before it repeats itself.

The tale of the dictator’s daughter and her prince

Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner are often viewed as a “moderating influence” on her father. But as their power in the White House grows and Donald Trump tightens his inner circle, this is looking more and more like a ruling dynasty. And this dynasty is no fairy tale.

The tale of the dictator’s daughter and her prince

Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner are often viewed as a “moderating influence” on her father. But as their power in the White House grows and Donald Trump tightens his inner circle, this is looking more and more like a ruling dynasty. And this dynasty is no fairy tale.

So you say you can’t say anything anymore

Being surrounded by middle-aged white people is nothing new for me. But my presence can apparently still seem something of a novelty. After an excruciating train trip, I can only conclude: the idea that racism is relegated to deplorables is elitist. And dead wrong.

So you say you can’t say anything anymore

Being surrounded by middle-aged white people is nothing new for me. But my presence can apparently still seem something of a novelty. After an excruciating train trip, I can only conclude: the idea that racism is relegated to deplorables is elitist. And dead wrong.