25 June 2020. In Kunamasi, a village in the mountains of northern Iraq, children are laughing and splashing about in the river. Next to them, tourists are hanging out under canopies made of palm fronds, lazing back on carpets, some of them smoking water pipes, others playing with their phones or drinking tea.

Rebaz Lawa (18), who works at his uncle’s shop at the riverside, is in his cellar when he is startled by a loud boom that shakes the ground. Outside, he sees that the windows in the neighbouring houses have been blown out. A man’s body is lying in the street, split in two. Giant flames come spewing out of the shop. Through the smoke, he sees his uncle coming out of the shop carrying his aunt, who is bleeding heavily. His nephew is sitting in the street, his face bloodstained.

The cause of the sudden death and destruction turns out to be a precision-guided missile fired by a drone.

It has killed its target, a high-ranking commander of the Kurdish organisation PKK. Three other rebels, waiting for their commander outside the shop, have been wounded. Lawa’s uncle, aunt and nephew have been hit by shrapnel, as have another villager and an Iranian tourist.

More and more countries are acquiring drones

These targeted killings may make us think of US drones. The US has carried out hundreds of drone strikes on places like Afghanistan and Pakistan since 2001. However, this attack was carried out by Turkey. And both the unmanned plane and the precision weapon with which the attack was carried out were made in Turkey.

More and more countries have acquired drones in the last few years, and have increasingly used them for deadly attacks. Until 2015, only the United States, the United Kingdom and Israel had carried out fatal drone strikes, but in the last five years, eight other countries have joined them.

Drones are having an enormous impact on the way war is waged. The most important change is that they make it much easier. Drones are cheap, you can use them to carry out attacks without endangering yourself, they provoke a lot less political resistance in your own country than if you were to send in soldiers and they are highly effective. Drones have played a leading part in virtually every war that has broken out or re-erupted this year.

Until 2015 only the United States, the United Kingdom and Israel had carried out fatal drone strikes, but in the last five years, eight other countries have joined them

They also have disadvantages. You can’t surrender to a drone. A target has no choice but to hide, flee or disappear into a crowd. As a result, in places where drones are widely used, society as a whole is under permanent, potentially deadly surveillance.

Turkey is at the top of the list of new drone users, but it’s also one of the world’s main manufacturers of drones. In under 10 years, Turkish defence companies have developed armed drones nearly as good as those made by established arms manufacturers in the US and Israel.

A look at these developments in Turkey helps us understand better how drone technology is proliferating all over the world. This understanding is also important in preventing arms technologies now being developed – like killer robots and swarming drones – from being used everywhere, with consequences you can (or can’t) imagine.

How Turkey couldn’t acquire drones …

In 1996, Turkey purchased its first unarmed US drones, says Engin Yüksel, a researcher at the Dutch Clingendael research institute.

Turkey had already been at war with the Kurdish militant separatist movement PKK, who were hiding out in the mountainous southeast of the country, for over 10 years. The Turkish army, finding it difficult to track down the rebels, thought that drones might solve the problem.

The drones would hover in the air for hours to pinpoint PKK fighters’ precise locations, after which an F-16 fighter jet would be sent in to launch an attack. But again and again, says Yüksel, by the time the F-16 had arrived at the site 20 minutes later, the target had already disappeared.

In 2006, Turkey ordered 10 unarmed Israeli drones. However, it took five years for Israel to deliver them, and they turned out not to work well. Moreover, they were operated by Israeli personnel. Turkish officials suspected that the images collected were being forwarded to the Israeli intelligence service.

At the same time, Turkey was trying to buy armed US drones that could attack immediately. But because Turkey had clashed more and more often with Israel since the Arab Spring, the fear arose that the technology would be used against Israel, and thus the US Congress refused to approve the sale of attack drones to Turkey in 2010 and 2012.

… and decided to make them itself

There was only one thing for Turkey to do: get to work developing its own. The two main players were Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI) and Baykar Makina.

TAI was licensed by the American company General Dynamics to manufacture Turkish F-16 fighter jets, which meant it already had useful knowledge for manufacturing attack drones. In addition, the company had already had a contract to develop an attack drone back in 2004.

More important was Baykar Makina, run by Selçuk Bayraktar, who had studied electrical engineering at America’s prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology and in 2005 returned to Turkey at the age of 26 to bring what he knew about drones back home.

In 2007, he interrupted his PhD studies to devote himself completely to developing armed drones in Turkey. Two years later, he won a contract for the production and sale of an armed drone: the Bayraktar TB2.

He imported high-tech parts that his company couldn’t produce themselves, such as the engine and sensors. Many of these parts could be used in either civilian or military applications, and were therefore not subject to export restrictions.

In late 2015 the TB2 had its first successful test, carrying a Turkish precision guided missile. From nearly 5,000 metres up, it hit a target eight kilometres away, accurate to within two square metres.

Almost immediately, the drones were deployed for their original purpose: intelligence gathering, surveillance and targeted strikes against PKK fighters. They were used in southeastern Turkey and the area near the border with northern Iraq, as well as over the border in northern Syria, where Syrian Kurds had controlled large areas of land since the outbreak of the war.

But drones quickly became useful for much more than hunting rebels.

How drones are changing warfare

Unlike the US and Israel, Turkey deploys drones not only against rebels, but also in war against armies of other countries, says Arda Mevlütoğlu, a defence specialist from Ankara.

Turkey deploys drones in coordination with electronic warfare, jamming enemy anti-aircraft and communications operations so that the drones can attack unimpeded. At the same time they also deploy other military units such as artillery and air force. The combination enables the Turkish army to swiftly and effectively attack enemies who lack modern arms technologies, says Mevlütoğlu.

Just how effective this is was shown in late February 2020. When the Syrian army, with Russian air support, wanted to stage a decisive strike on the last rebel-controlled bulwark in the Syrian province of Idlib, the Turkish drone fleet attacked mercilessly.

In a few days’ time, 2,557 Syrian soldiers were killed and two drones, eight helicopters, 135 tanks, two jet fighters, dozens of howitzers and five anti-aircraft systems were disabled, according to the Turkish defence minister Hulusi Akar.

Another victory came in June. After a siege of more than a year the Libyan general Khalifa Haftar had been on the point of taking the Libyan capital Tripoli, seat of the internationally recognised government of Fayez al-Sarraj. Turkish drones came to Sarraj’s help, and Haftar’s forces were driven back within a week.

In late September, Turkish drones played a similarly crucial part in the region of Nagorno-Karabakh, a point of dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan since 1991. After six weeks of heavy fighting, the Armenian president Nikol Pashinyan signed a peace treaty in early November, which meant de facto capitulation for Armenia.

In all of these military confrontations, the use of Turkish drones combined with electronic warfare and the use of precision guided munitions created an asymmetry that turned the tide in favour of Ankara or the party that Ankara was backing, says Clingendael researcher Yüksel. “That shows technology matters.”

Since as many components of Turkey’s drones as possible are manufactured domestically, Turkey is not dependent on foreign companies who can be banned from exporting drones. This enables them to evade international pressure, Yüksel explains. “It gives Ankara a kind of independence in projecting military power outside Turkey.”

Turkey wants (a lot) more

The drones have now become a symbol of Turkish national pride. No one criticises their potential for inflicting civilian casualties. Selçuk Bayraktar has even become a national celebrity. In May of 2016, less than six months after his first successful test of a precision strike, he married President Erdogan’s youngest daughter Sümeyye.

Now and then the president will show up to autograph his son-in-law’s latest drone models, while governors in the southeast of the country take regular trips to the hangars where the drones are kept, to praise them and to pray for the well-being of their operators.

Now and then the president will autograph his son-in-law’s latest drone models

In the meantime, Turkish defence companies are hard at work developing the next generation of drones. The priorities are a greater range, the ability to use heavier ammunition and that they be manufactured as much as possible domestically.

The Turkish army is striving to be completely self-sufficient by 2023.

This self-reliance is also a necessity. As it did previously, Turkey is again facing import restrictions. On 5 October of this year, Canada banned the export of engines and high-tech sensors for Bayraktar TB2 drones because of the excessive force used in Nagorno-Karabakh. The day after this decision, Turkey’s highest procurement official Ismail Demir tweeted that Turkey would be manufacturing the optic systems itself.

Drones could also reduce Turkey’s dependence on foreign jet fighters in the near future, says Yüksel. This is significant, because since last year there has been an embargo on the sale of the US F-35 fighter jet, the successor of the outmoded F-16, because of Turkey’s purchase of a Russian anti-aircraft system.

Turkey is even intending to develop its own domestically made fighter jet in order to avoid any potential problems caused by its dependence on foreign defence equipment, as became clear with the purchase of the F-35, he continues. “The expertise they acquired in producing the drones could be very useful here.”

Turkey is not alone

Turkey’s approach demonstrates not only that it pays off for a country to make strategically important weapons technology domestically, but also how relatively easy it is. Less than five years after the first successful missile test with a Bayraktar TB2, Turkey is now one of the world’s top users and producers of attack drones.

Azerbaijan, Qatar, Ukraine and the Sarraj government in Libya now possess Bayraktar TB2 drones. TAI is also in talks about exporting drones to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Turkish drones have proved their worthiness in battle, are far cheaper than American or Israeli models and moreover are not subject to import restrictions.

China, Iran and Pakistan have also built up impressive drone industries

But Turkey’s approach is not unique. China, Iran and Pakistan have also built up impressive drone industries in the last few years, and are manufacturing some formidable high-end attack models.

Even countries like South Africa, Poland and Belarus are developing drones. Like Turkey, they seem to be perfectly capable of developing technology that until recently was almost exclusively in the hands of the US and Israel.

The consequences can be seen on the battlefield. In Ukraine and Yemen, at least 40 different kinds of drones from twelve different countries are in use – ranging from small commercial models to large military drones, the peace organisation PAX reported in September.

Libya, sometimes called “the world’s largest drone-war theatre”, also has military drones from various other countries, including the Turkish Bayraktar TB2, the Chinese Wing Loong, the Russian Orlan-10, the Yabhon from the United Arab Emirates, the American Reaper, the Iranian Mohajer, the Israeli Orbiter and dozens of smaller commercial hobby models.

“Drones have become the ultimate instrument for countries who are unwilling to send in soldiers but who see the need to use armed force,” says PAX researcher Wim Zwijnenburg.

The ease with which countries deploy their drones concerns him. Because, he warns, this is just the beginning. As more countries make drones, the cheaper they will become, and more countries will buy and use them. Since much of the technology necessary to manufacture drones is used for both civilian and military purposes, it can be spread quickly and continue to develop.

And that in turn gives rise to new concerns. In June, the Turkish army reported that they had operationalised 500 swarming kamikaze drones. Weighing under seven kilos each and laden with explosives, these mini-drones seek their target independently, then crash into it, writes Turkish press agency Anadolu.

Armies all over the world are investing in weapons systems that can perform more and more tasks independently, like autonomous drones and unmanned ground vehicles. China recently set a new record by sending a swarm of 3,051 drones into its airspace simultaneously.

These kinds of technologies are the future, says Zwijnenburg. “And I expect that in five to ten years they’ll be as commonplace [in battle] as drones are now.”

‘That fear will never leave you’

Four months after the Turkish drone strike in Kunamasi, peace seems to have returned to the village. A few geese scratch around in the now-mostly dry riverbed, and hundreds of small birds have lit in the scrubby oaks on the mountainside next to the village.

If you didn’t know that the pothole in the road was made by a precision guided bomb and the pits in the traffic sign a little further along were from shrapnel, you probably wouldn’t even realise that a new kind of war is raging here. Yet since June, at least 10 attacks of this kind have taken place, in which civilians were killed, states the research collective Airwars.

Since the attack, life in the village has changed, says Rebaz Lawa, who has taken over his uncle’s now-rebuilt shop. “Everyone is constantly on their guard. The other day when a car tire exploded, everyone panicked. Five days ago, there was a drone hovering in the air for hours. When that happens, people close up their shops and go home.”

Lawa: “I used to think that the drones wouldn’t hit us. Now I’m not sure. You can always be a target. That fear isn’t going away.”

This story was partly made possible with support from the Postcode Loterij Fonds of Free Press Unlimited.

Translated from the Dutch by Anne Hodgkinson.

About the illustrations

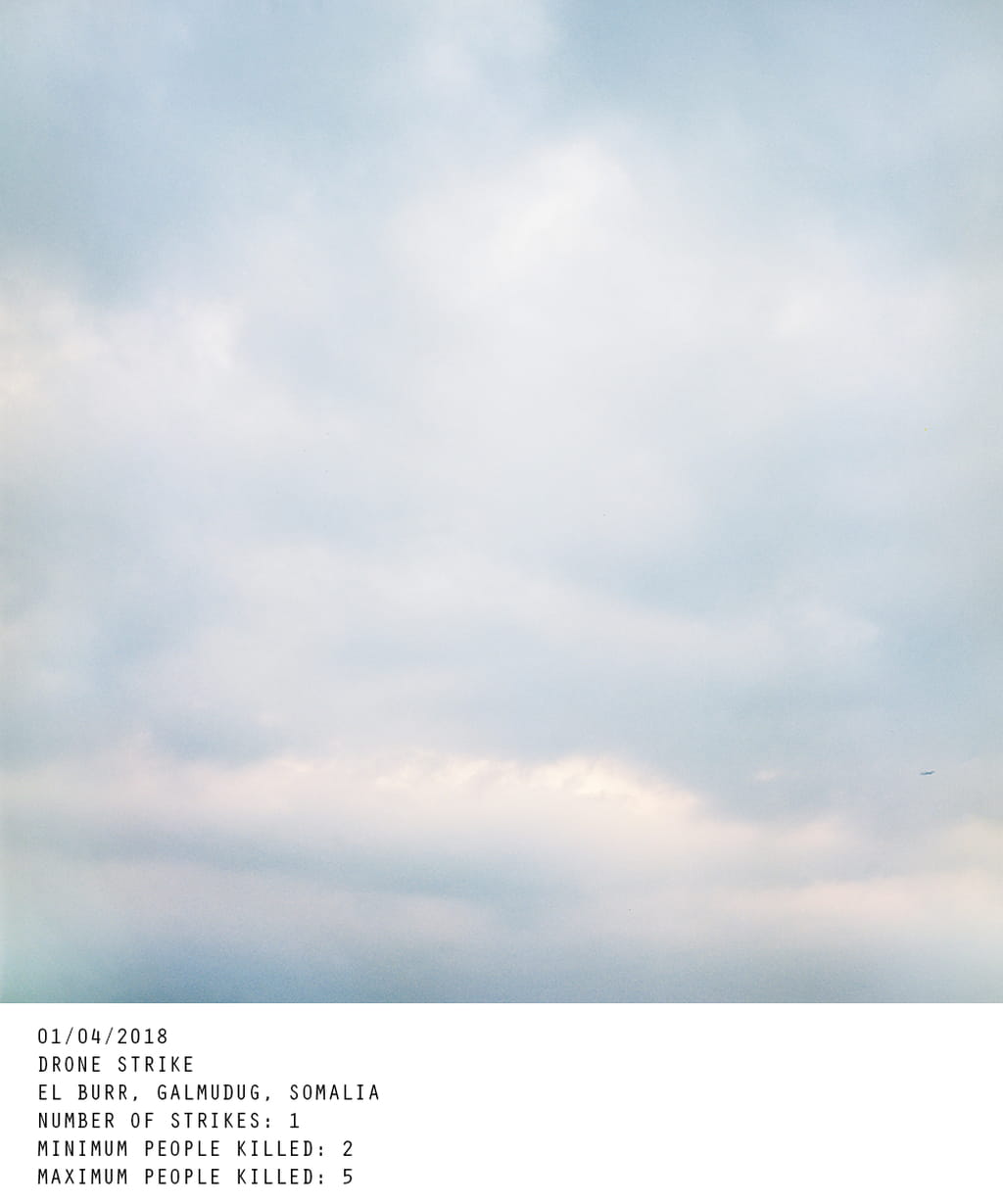

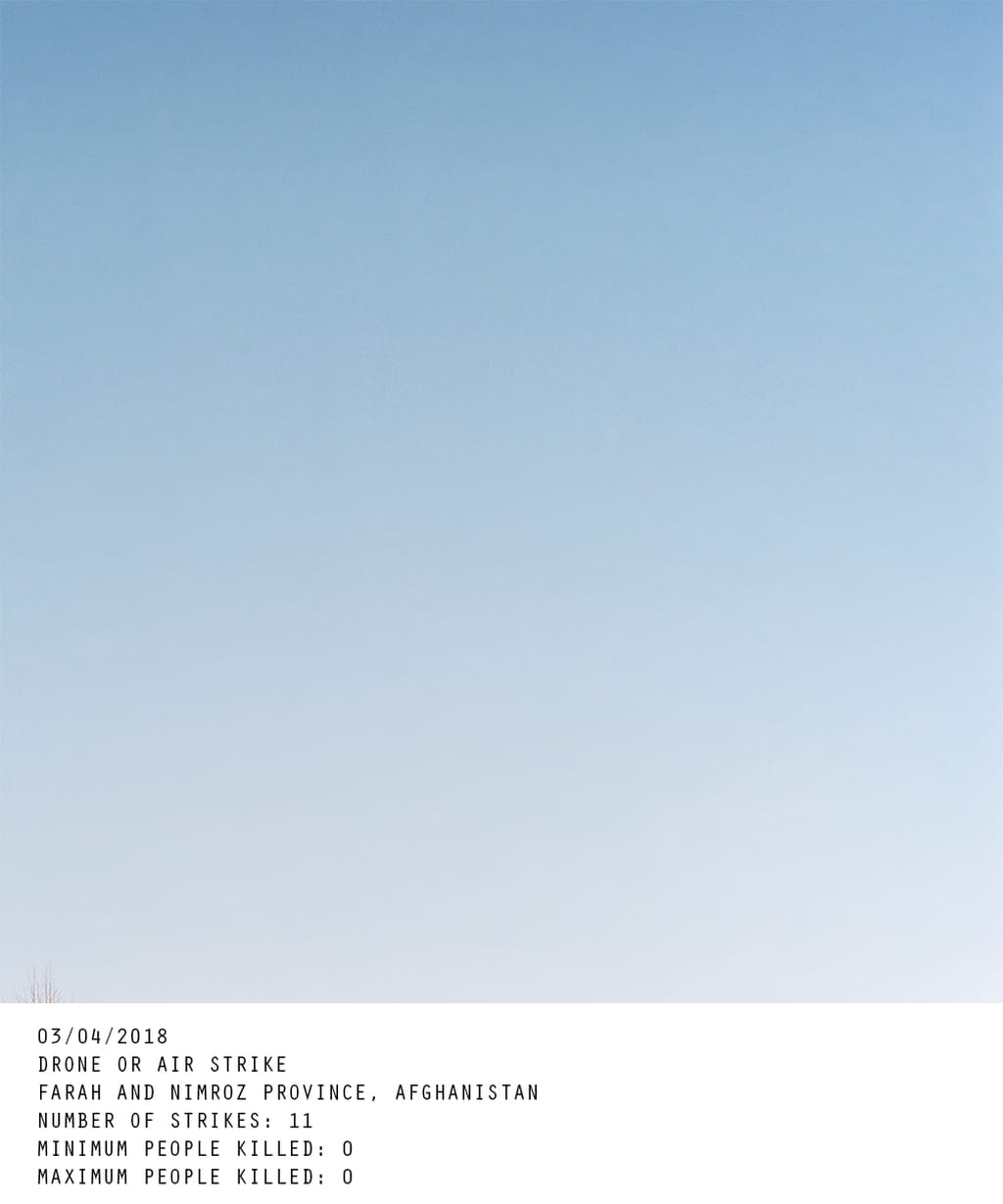

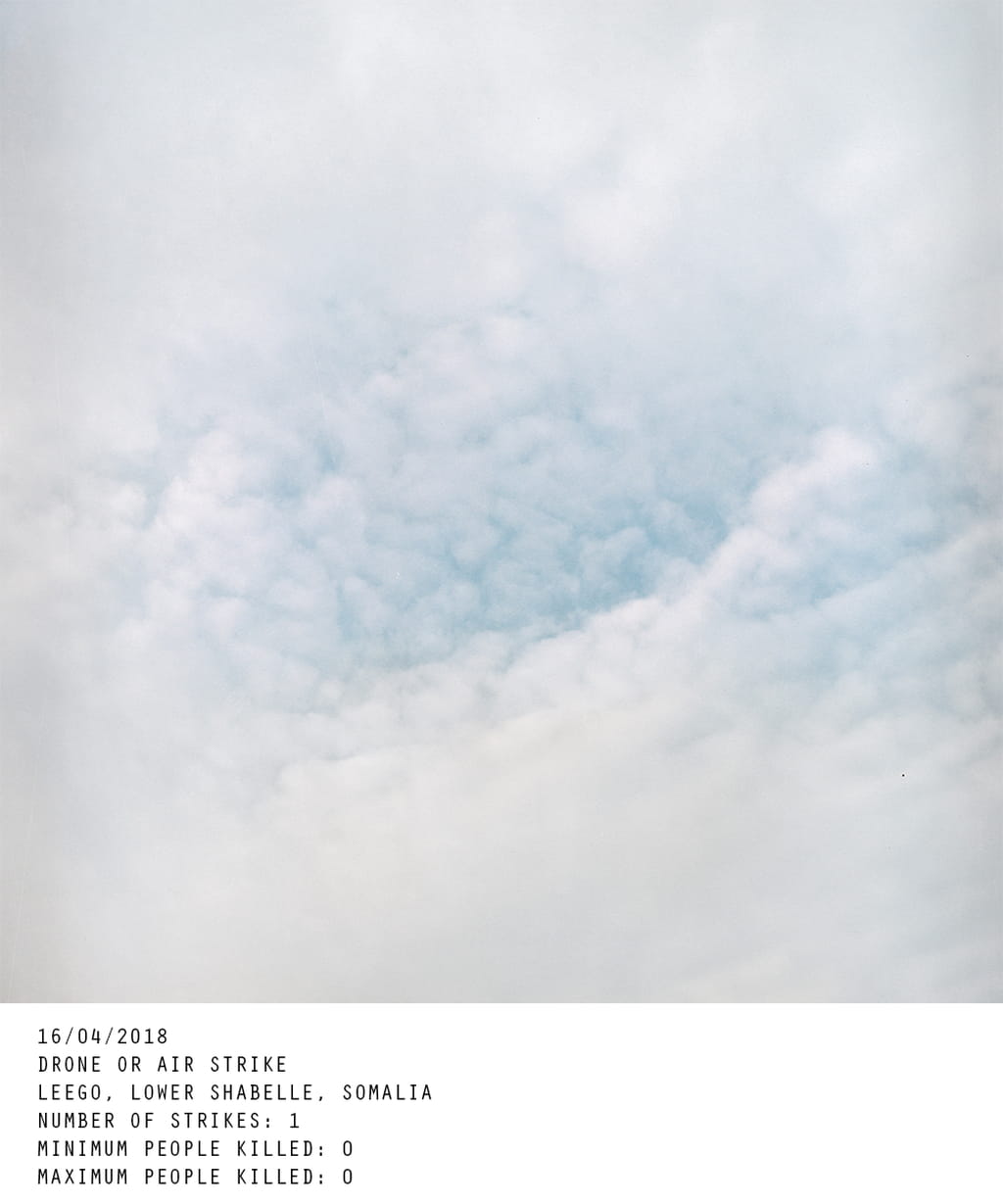

Every day in the spring and summer of 2018, the Dutch-Iranian photographer Tina Farifteh took a photo of the morning sky. Whether it’s a blanket of grey clouds, the sun breaking through or even cloudless and brilliant blue, all of them look familiar and innocent. Until we read the captions.

About the illustrations

Every day in the spring and summer of 2018, the Dutch-Iranian photographer Tina Farifteh took a photo of the morning sky. Whether it’s a blanket of grey clouds, the sun breaking through or even cloudless and brilliant blue, all of them look familiar and innocent. Until we read the captions.Later on, Farifteh used the London Bureau of Investigative Journalism databases to connect her pictures to days when there had been a US drone attack. She found out that there had been an air strike on average once in four days on Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia or Yemen. The shocking discoveries turn her skies into an unpredictable enemy.

With the Killer Skies series Farifteh questions a remotely waged form of warfare, which a growing number of countries are becoming interested in. What does it do to you when the sky above you can become a lethal battleground?

Veerle van Herk, image editor

Dig deeper

Drones have changed warfare. This is what life is like as a constant human target

The use of drones fundamentally changes the nature of war. The pilots are invisible and untouchable, with a terrible price being paid by ordinary citizens. Turkey’s military operation in northern Iraq reveals that all too clearly.

Drones have changed warfare. This is what life is like as a constant human target

The use of drones fundamentally changes the nature of war. The pilots are invisible and untouchable, with a terrible price being paid by ordinary citizens. Turkey’s military operation in northern Iraq reveals that all too clearly.