"EXCITED to share that our comment ‘The missing global in global mental health’ is now available online."

Not every academic article warrants such exuberant tweets. But what Maji Hailemariam, assistant professor at Michigan State University’s College of Human Medicine, announced to the world on 19 November wasn’t a dense entry in some obscure journal. It was the culmination of a unique collaboration to address a deep-seated historical wrong, with implications going far beyond the closeted world of the academia.

Hailemariam, who is from Ethiopia, had co-authored a sharp critique of one of the world’s most prestigious mental health journals – The Lancet Psychiatry. By extension, the comment called out the glaring defects in the grandiosely named "Global Mental Health" (GMH) movement that the journal’s parent publication, The Lancet, had played a key role in incubating a little over a decade ago.

Elsewhere on this website, I’ve analysed the failings of the GMH movement, which was expected to tackle the unique and neglected mental health challenges in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

The gist of it is this: this so-called "global" project isn’t global at all.

Global mental health is still controlled by an elite club of funders, researchers, practitioners, et al, located in high-income countries (HICs). LMICs and people with actual lived experience of mental health challenges – the intended beneficiaries of the movement – are still far from being an equal and active part of the conversation. There’s still not enough appreciation that mental health is a complex ping pong between your biology and your environment, and that everything from your skin colour, gender and sexuality to your economic status and politics has a bearing on it, more than just the serotonin levels in your brain.

In other words, global mental health has ended up becoming exactly what it sought to resist: a neo-colonial echo chamber.

The piece Hailemariam co-authored called out serious problems in The Lancet Psychiatry’s own practices that reflect these larger maladies. The immediate trigger was a position paper on the global mental health challenges posed by Covid-19 that the journal had published in July. The paper’s supposedly "international" group of 24 authors had no representatives from LMICs of Africa and Asia (except China), which together account for more than half of the world’s population. Most of the evidence in the paper was from HICs, and all but two of the authors were also from HICs.

"We in Africa are not concerned by this paper," an angry Twitter user had then shot back. "Why are there not any African institutions involved in this paper? Why are some academicians from high-income countries so short-sighted when it comes to key global health questions?"

This might not have been a one-off lapse: of The Lancet Psychiatry’s 50 editorial board members, a mere eight belong to LMIC institutions, only four are black, and only eight are Asian (but only four of them are based in institutions in Asia). Three of the board members identify as service users; only one of them is from an LMIC.

The academia can be notoriously thin-skinned ( "I’ve never seen a group of people – including investment bankers – more obsessed with status," the US columnist Megan McArdle once wrote about professors). But in a highly symbolic departure from this stereotype, The Lancet Psychiatry decided to publish the critique on its own site.

In another subversion of the hidebound traditions of the academia, Hailemariam and her co-author, the Indian psychiatrist and mental health policy advocate Soumitra Pathare, had never met in person. They had found each other in the same place where I found them: Twitter.

Why do we need a global mental health movement?

The concept of GMH started formally gaining currency in 2007, after The Lancet published a series of articles addressing the high incidence of mental health problems and poor access to services in LMICs. These countries bear a disproportionate burden of stressors such as violent conflict and displacement (for instance, Hailemariam’s home country is in the throes of bloody political violence, leaving thousands homeless), and domestic violence (during the first four phases of the Covid-19 lockdown, Indian women filed more domestic violence complaints than in a similar period in the last 10 years). They call for an approach firmly rooted in these social realities rather than the overly medicalised and individualised model prevalent in the west and exported to the rest of the world.

Two years later, in August 2009, a landmark Global Mental Health Summit was convened in Athens. Its aim was to promote mental health awareness, tackle stigma, and push governments to frame mental health-friendly policies.

Here’s a handy definition of GMH in The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA): "Global health is ‘an area for study, research and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide’. Global mental health is the application of these principles to the domain of mental ill-health."

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) adds that global mental health "takes into consideration disparities in mental health treatment and care across cultures and countries".

What kind of "disparities"? Pretty devastating ones. According to JAMA:

- LMICs are home to over 80% of the global population, but command less than 20% of the share of the mental health resources.

- This is a contravention of basic human rights – more than 75% of those identified with serious anxiety, mood, impulse control or substance use disorders in the World Mental Health surveys in LMICs received no care at all.

- In sub-Saharan Africa the treatment gap for schizophrenia and other psychoses can exceed 90% ...

... and so on.

A failed revolution

The call for "equity" is well-meaning and rousing. Except most such widely cited manifestos of "global mental health" are issued by out and out North American or European platforms.

Here’s an experiment: go ahead and Google "what is global mental health?". How many Asian or African publications or perspectives did you find?

There are several fallouts of this disparity, the most critical ones being:

- a stubborn over-dependence on western systems of classifying mental illnesses (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual or DSM, for instance);

- the continued primacy of the biological – or "chemical imbalance" – model of mental illness, despite perpetual controversies about the absence of concrete scientific evidence;

- the resultant concentration of power in the pharma industry; and

- the erasure of the role played by local, socio-cultural factors in shaping the experience of mental distress.

Add to these the half-hearted commitment of the very same platforms that had blown the bugle of change, and you get the sour aftertaste of a failed revolution.

A new revolution needs new spaces

After it received backlash on Twitter for its July paper, The Lancet Psychiatry was quick to respond with a radical confession: it is game over for global mental health as we know it. We urgently need a new playbook. I had then said that this was every bit as momentous as McKinsey calling game over for capitalism as we know it.

"It is a concern that ‘global mental health’ contains assumptions about knowledge and expertise that are inimical to the very populations it purportedly sets out to help," the journal’s editors wrote in an extended mea culpa. "Without sufficient forethought, global mental health may become a globalised iteration of psychiatry’s potential to reinforce existing power structures and hierarchies."

It acknowledged the particularly grave dangers of this power imbalance in the aftermath of Covid-19. "As Sarah Dalglish of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and University College London put it in a letter to The Lancet in April, 2020, "Global health will never be the same after Covid-19 — it cannot be. The pandemic has given the lie to the notion that expertise is concentrated in, or at least best channelled by, legacy powers and historically rich states."

The Lancet Psychiatry was quick to respond with a radical confession: it is game over for global mental health as we know it

The editorial took note of Hailemariam and Pathare’s tweets criticising the paper, which began a chain of correspondence that led to their co-authored comment.

"This collaboration came about after Dr Pathare and I read the [July] paper and took it to Twitter because we couldn’t believe our eyes," says Hailemariam. "I didn’t know of Dr Pathare or his work before this incident. We were each offered an opportunity to write a correspondence letter or a comment after we tweeted about the issue tagging the journal (the editor Niall Boyce reached out to us). We talked about it and agreed to join forces. I agreed to lead."

On his part, Pathare – who has long used Twitter to shape public opinion in India on complex issues such as suicide prevention – says the collaboration across time zones via email and video calls was "fun and a really pleasant experience". The psychiatrist, who has helped shape mental health policy and legislation in a number of LMICs such as India, Lesotho and Eritrea, also praises the journal’s role in making space for their comment notwithstanding its strong criticism.

Where do we go from here? For all its clout, a journal is still a terribly limited and exclusive haven for privileged writers and readers. It can only push the vast, nebulous goal of reinventing the idea of global mental health so much.

Hailemariam and Pathare argue that we need to begin by recasting how we understand and use the word "global". Global can’t just be a geographical concept anymore. Between its two syllables, it must hold the entire gamut of human experiences.

"We call for an alternative interpretation of global as comprehensive, inclusive, and embracing all — eg, cultures (countries and regions), stakeholders, and sectors in all endeavours extending from research, policy development, and mental health services," they write.

As a show of intent and to set an example, they invite The Lancet Psychiatry to conduct a regular audit of its diversity practices, including the composition of its editorial board, authors and peer reviewers.

Does this reckoning signal real change, or will it be another false dawn? It’s too early to tell. But to me, this episode is an exciting reminder of the shifting locus of meaningful change – and indeed, of the fact that change is possible, even in the most monolithic places. Groundbreaking alliances and new combat strategies to take on old hegemonies can now play out 240 characters at a time. The revolution will not be televised. It will be tweeted.

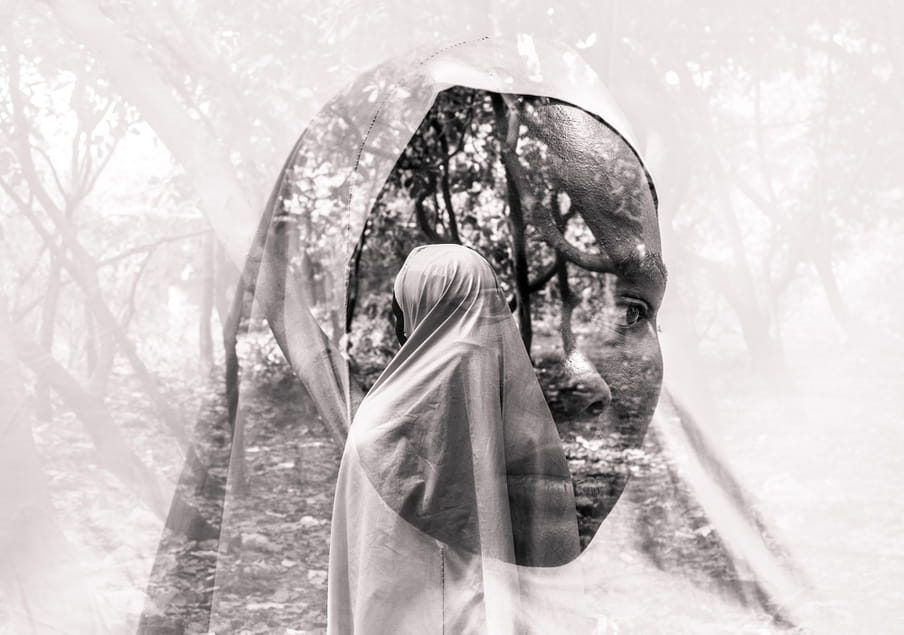

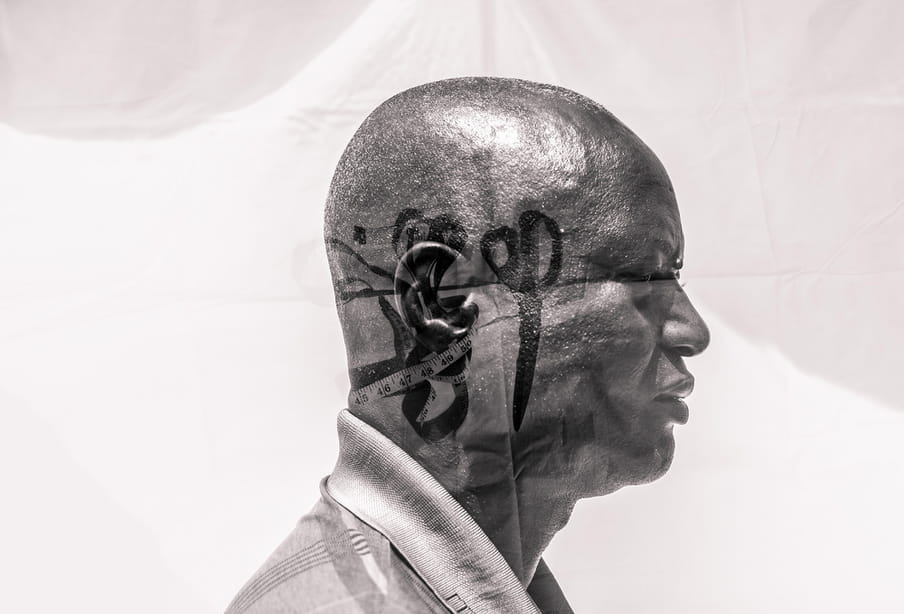

About the images

‘It’s All in My Head’ is a multimedia project by Etinosa Yvonne that explores the coping mechanisms of survivors of terrorism and violent conflict by using layered portraits (still images, videos and letters) of the things they do to help them move forward. The project aims to advocate for increased need for access to psychosocial support for the survivors, which in turn will improve their mental health.

About the images

‘It’s All in My Head’ is a multimedia project by Etinosa Yvonne that explores the coping mechanisms of survivors of terrorism and violent conflict by using layered portraits (still images, videos and letters) of the things they do to help them move forward. The project aims to advocate for increased need for access to psychosocial support for the survivors, which in turn will improve their mental health. In the last two decades, Nigeria has witnessed varying degrees of terrorism and violent conflicts. Whenever there is an attack, little priority is given to assessing the mental health of survivors.

Exploring the coping mechanisms of these individuals gives an insight into how these survivors struggle to move on amidst little or no psychosocial support. (Veronica Daltri, image editor)