Hi,

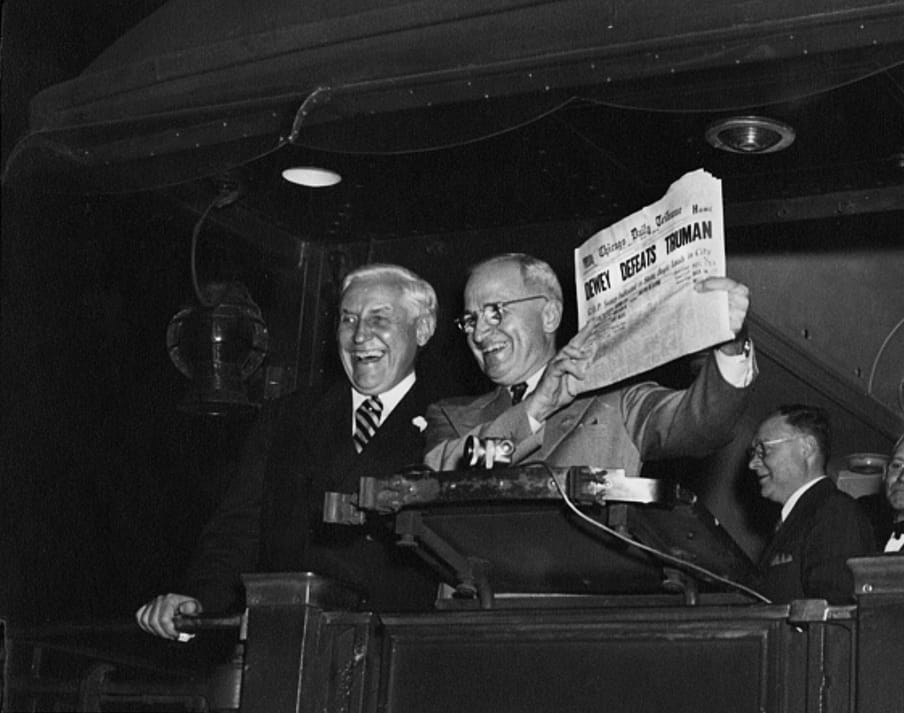

This black and white photo is from 1948. If you look carefully, you see the headline on the front page: ‘DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN’.

The moment is iconic, but not because presidential candidate Thomas E Dewey won the American elections. It is iconic because he didn’t.

The man in the picture is Harry S Truman, Dewey’s challenger. And the newspaper in his hands was completely wrong. The editor-in-chief of the Chicago Daily Tribune had been so convinced of Dewey’s victory – based on the polls – that he hadn’t even waited for the result and had already printed the fat headline on election night.

Fast forward to November 2016. We could have seen a similar picture then, this time with Donald Trump. In his hands one of the many newspapers that had predicted that Hillary Clinton would win. A big smile on his face, because she didn’t.

"How did he pull off such a stunning victory?", The New York Times wondered the day after the elections. "How did almost no one – not the pundits, not the pollsters, not us in the media – see it coming?"

Princeton professor Sam Wang had predicted, based on polls, that Clinton had a 99% chance of winning. If Trump won, he promised, I’ll eat a bug. It tasted "nutty", he said, when he ate a cricket on a live CNN broadcast four days after the election.

Were the polls wrong?

Were the polls wrong in 2016, just like they were in 1948? It was a popular narrative, especially right after Trump’s victory. Only: it was too easy to blame the polls.

Polls are never accurate, that’s the nature of the beast. After all, only part of the entire population is interviewed. Those people will rarely be a perfect reflection of society. There might be a few extra Republicans, or a couple more Democrats.

That is why polls always have a margin of error. That bandwidth indicates that the actual result may be somewhat above or just below the calculated percentage (often with a probability of 95%, so there may still be some outliers beyond the margin).

And while many newspapers in 2016 stated that the polls for the US elections had been magnificently wrong, this was nonsense if you look at the error margin.

At the state level, polls generally did fine. Okay, in some states, pollsters had fumbled. For example, in the state of Wisconsin, Trump did 6 percentage points better than the Marquette Law School poll had predicted, and in the suburbs of Milwaukee as much as 10 percentage points.

But, as data journalist and FiveThirtyEight editor-in-chief Nate Silver writes in his post-mortem analysis of the elections, the polls were as accurate as they have been, on average, since 1968.

The popular vote – the vote among the entire US population – was not surprising either. Trump scored between 1 and 2 percentage points higher than the polls predicted, while a reputable pollster such as ABC News/Washington Post reported an uncertainty margin of 4 percentage points. Within the margin.

So there was nothing crazy about Trump’s victory if you had looked at the polls. Moreover, the difference between the polls and the results was even less than in 2012, when no one complained about the figures.

It wasn’t the polls that had erred in 2016, it was the media.

And now what?

The difference between Biden and Trump is bigger than between Clinton and Trump in 2016 (for the record: with Biden ahead). The polls must be a lot more wrong this time if The Donald wants to win again.

But, wrote Silver this weekend, that’s not impossible. In his own model he gives Trump a 10% probability to win. So the chance is not zero. He lists a number of reasons:

- In swing states that can tip the election, the difference between Trump and Biden is smaller than in the popular vote.

- In Pennsylvania, the state that is important for the victory, Biden is ahead but the lead is not overwhelming.

- There may be structural errors in the polls (for example, a certain group of Trump voters could be undetected by polling), and these are difficult to predict.

- There may be a recount or a tie in the electoral college.

- Finally, there are scenarios in which Trump could achieve an illegal victory (enter: one of the many "what if Trump doesn’t want to go" articles of the past weeks). Silver doesn’t take this into account in his predictions.

I’ll be ready for the election night with popcorn and Budweiser (read more about the media hype around elections in Nesrine Malik’s column).

Maybe Biden will get a resounding victory, maybe Trump will surprise us once more, or there might still be no clarity when I dive into my bed.

Reading and listening tips

Feel like diving further into the American elections? At The Correspondent we list a number of tips: sources we follow to put the elections into context and our own journalism on the subject.

Personally, I can recommend the following:

- FiveThirtyEight, you might have noticed, is a website I like to follow when it comes to data about the American elections. Sophisticated and well thought-out analyses of the figures, while also stressing what we don’t know. And while you’re at it, don’t forget to read Nate Silver’s Signal and the Noise. Already a few years old, but still relevant if you want to understand more about forecasting.

- Historian Jill Lepore created the beautiful podcast series The Last Archive, in which she looks for an answer to the question: who killed truth? With historical examples she touches upon themes such as the anti-vaccine movement, MeToo and climate change. In episode 5 she talks about the American elections of 1952, when for the first time a computer predicted the elections – the ‘UNIVAC’ on television channel CBS. Dwight D Eisenhower’s landslide victory over Adlai Stevenson was a surprise. The UNIVAC had predicted it, but it was never broadcast; CBS had simply not believed the forecast.

- Where does the polarisation in the United States come from? That is the central question in Ezra Klein’s book Why We’re Polarized. Klein is himself a political reporter and co-founder of the journalistic platform Vox. In the book he looks at the problem of polarisation from different angles. Historically, for example, political parties were more diverse than they are today. Psychologically, Klein argues, we tend to think in "tribes" and defend our own club. Would you like to hear a critical reflection after reading? Jill Lepore questions Klein’s work in his own podcast show.

- I’ve talked about the book before: Strangers in Their Own Land. Sociologist Arlie Hochschild immersed herself for years in an archconservative region in America, in order to better understand why people have such a different political preference than herself. A nice insight into right-wing America, and a lesson on how to have better conversations with people who think differently from you. Read more about it in my review of the book.

Before you go...

Correlation is not causation – it’s a well-known maxim. It’s easy to refute a causal relationship, much harder to prove one. So how do you do it? In my latest article for The Correspondent, I take a deep dive into the science of cause and effect.

Part of this newsletter comes from my book The Number Bias (translated by Suzanne Heukensfeldt Jansen). With thanks to colleague Lynn Berger, who recommended The Last Archive to me.

Prefer to receive this newsletter in your inbox?

Follow my newsletter to receive notes, thoughts, or questions on the topic of numeracy.

Prefer to receive this newsletter in your inbox?

Follow my newsletter to receive notes, thoughts, or questions on the topic of numeracy.