“Your mother breastfed you until the age of four?! Yuck!”

I was in my early twenties, sitting on a cushion on the floor of the living room of my flat in Santiago, Chile. Some visiting friends and I were all shocked when Marcela, my flatmate, confessed that she remembered the taste of breast milk because her mother had breastfed her and her younger siblings for many years.

The feeling in the room was unanimous – we were grossed out. How could a mother feed a child who already speaks and walks and will remember the experience vividly? We even had a psychologist among us who ventured into Freudian interpretations of how pathological Marcela’s relationship was with her mother.

Fast forward 15 years, and here I am, still breastfeeding my 20-month-old son Lorenzo, with a full understanding of how good it is for him to have access to this superfood, while developing a very secure attachment to me.

So, why was I even commenting on breastfeeding in my early 20s with no knowledge at all? Why was a psychologist cornering my friend Marcela like that, with cheap, old-fashioned interpretations? Why was everyone in the room disgusted?

It didn’t help that I had never seen a mother breastfeed beyond infancy. I didn’t even remember my younger brother breastfeeding, as my mom nursed both of us for only five months, following her doctor’s advice.

As I started writing about breastfeeding, I realised that I myself had a lot of unpacking and unlearning to do.

So let me guide you through six myths about breastfeeding – ideas that are so deeply ingrained that I’ve also been guilty of sharing them with others in the past.

Myth #1: Breastfeeding is free

This is a tagline for a lot of campaigns – especially aimed at those living in poverty – that breastfeeding is the cheapest option available. I also thought of breastfeeding as free when I first reported on it years ago, thinking it should be a no-brainer for mothers.

Ha, how naive was I?! I didn’t realise just how much time breastfeeding takes until I became a mother myself. In my son’s first months, he was attached to my breast some 12-14 hours a day. Did I still think of breastfeeding as free? Certainly not. As journalist Hanna Rosin wrote: “It’s only free if a woman’s time is worth nothing.”

Breastfeeding is a form of reproductive labour, or care, which is never taken into account in the GDP because it doesn’t “produce” anything concrete. By contrast, the market value of milk formula production and sales are counted.

“Breastfeeding is an example of how the economy is mismeasured,” say economists Julie P Smith and Nancy Folbre. Smith estimates that breast milk production in Australia each year is worth about US$4bn, much more than the baby food industry all together.

There is also a mental cost to breastfeeding, which is rarely talked about

You also have to count on the products and services that you may need in order to breastfeed: creams for your cracked nipples, bras and tops that make reaching for the boob faster, pads that avoid staining your tops with whatever leaks, breast pumps, containers and bottles in case you need to freeze your milk. And if you, like most others, need some help in the process, you may have to pay for a lactation consultant too.

Breastfeeding also has a huge caloric cost. The cumulative energetics of pregnancy and lactation are estimated to consume some 200,000 calories, which the mother needs to make up for by intaking more calories. A friend and I often joke about how we lactating women are always ready for a snack, and it is true!

There is also a mental cost, which is rarely talked about. Women feel guilty when they think they “fail” at breastfeeding. Others feel resentment and downright anger towards the child constantly attached to the boob, and then guilt and shame for their negative feelings. And even when everything else is in order, there are different levels of comfort, and different cultural standards, for women to breastfeed in public. Whichever way you see it, breastfeeding is not “free” from an emotional perspective.

Myth #2: Breastfeeding is natural and therefore spontaneous and easy

Wait, there’s a profession known as lactation consultant? You’ve probably heard that breastfeeding is natural, so why would you need someone to advise you on how to lactate?

I had read about how newborns naturally gravitate towards the nipples. But I was amazed to experience how my son, soon after coming out of my vagina and being placed on my belly, immediately started sniffing around, looking for my nipple. He somehow managed to find it and drag himself towards it, and started sucking immediately, as the midwives were still helping me expel the placenta.

Breastfeeding is natural inasmuch as it is a product of evolution. In this sense, it is part of our nature as Homo sapiens to feed our infants at our breast. But that does not make it easy.

In fact, I spent most of Lorenzo’s second night of life in tears as he screamed because he was hungry and I did not know how to attach him properly. Then there were a few gruelling days until there was a proper letdown of milk. When that happened my boobs hardened up and felt like botched silicone implants. I had to massage myself under a hot shower for hours to let go of the pain and help Lorenzo get access to milk.

I was lucky enough to have access to midwives and a free birthing class that put a lot of emphasis on potential issues: my son may not latch on properly, and my nipples may start to bleed (they did); if he didn’t eat enough, I could get clogged up and even get mastitis as a result.

There are also some women who can’t lactate, and men who do. That is natural too.

Breaking up the meaning of the word natural is important because breastfeeding doesn’t happen spontaneously, like urinating. On the contrary, it requires high support.

One more thing: we’ve come to associate the idea of “natural” with “good”, especially when it comes to pregnancy, childbirth and early childhood. But you know what’s also natural? A wasp paralysing a spider and laying its eggs in the spider’s stomach to gestate, and then devouring the spider after the eggs have hatched. Baby sharks eating their siblings up while still in utero. In other words: whether or not something is natural doesn’t say very much at all about whether it’s also good for us.

Myth #3: Breastfeeding improves a child’s IQ

As I started reading up on breastfeeding, I got lost in dozens of claims, some of which I also replicated in the first newsletter I wrote about the issue. (Mea culpa, I will update that!!)

The most incredible claim is that children who are breastfed will have a higher IQ than those who aren’t. What parent would not take their breasts out for this promise alone?

As it happens, IQ is not the best way to test a person’s intelligence, though it provides a standard that is easier to follow in studies. More importantly, there is no compelling evidence showing that breastfeeding determines a higher IQ. Economist Emily Oster breaks down some of the studies about breastfeeding in her book, Cribsheet. The main issue with these studies, she explains, is that it is mainly more highly educated, richer mothers who decide to breastfeed, and it is very hard to separate the impact of breastfeeding on IQ from the impact of all the other socio-economic factors on IQ.

Even in studies that pick mothers from the same socioeconomic background, like this comprehensive study in Brazil, the authors recognise that it is hard to find a direct causation between breastfeeding and higher IQ.

The bottom line is that, even if there is a difference, it is hard to prove that it was caused by breastfeeding alone.

Debunking this is important because we need to give people who can’t or don’t want to breastfeed support too, instead of stigmatising them.

Myth #4: Breastfeeding is just a source of calories

I must admit that one of my very first worries when thinking about breastfeeding was how much my child would eat, and whether it would be enough. I knew of doctors who asked mothers to weigh their kids before and after feeds to see whether their kids were eating enough. But imagine if you were weighed before and after every meal, as if your needs and desires were constant day after day.

The point is that breastfeeding is not just about a transferral of calories. It is not just a simple meal. While breastfeeding, the baby is in direct contact with the mother, and a dialogue takes place, with an exchange of glances, touching and sounds. (Look, I know, I have also taken advantage of breastfeeding to read and message friends, but overall I do interact very closely with Lorenzo when I am nursing him.)

Many scientists think that human milk may adapt to a child’s needs when the child sucks, highlighting that many of the possible benefits of breastfeeding may come from the mother-child interaction, not the milk itself.

This matters because if the mother-child interaction is essential to breastfeeding, then we need to rethink which policies can actually support this. If we put more emphasis on the process rather than the product, then expressing milk may not be enough.

Myth #5: Breastfeeding has an expiry date

Let’s go back to my very first misunderstanding about breastfeeding: how grossed out I felt by my friend Marcela’s experience of breastfeeding until she was a toddler.

It turns out that Marcela’s mum was right – breastfeeding doesn’t have an expiry date. The World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life and continued breastfeeding until two years of age or beyond.

Most research focuses on breastfeeding in the first six months of a baby’s life, but very little has been carried out on extended breastfeeding. For example, we don’t know much about how much milk composition changes when lactation is sustained for multiple years, or for mothers who tandem feed (who feed two children of different ages at the same time). We do know, however, that in different societies and countries around the world, breastfeeding ends between the age of two and four. And if we look at our closest primate relatives, chimpanzees and gorillas, they wean between the ages of three and five.

So, is there a preferred duration of breastfeeding? Despite what I and my friends thought over a decade ago, and despite what some paediatricians may still tell you, there is no clear evidence that there is an optimal age for breastfeeding, and it is very much up to parents, cultural norms and work commitments.

Myth #6: Breast is best

You probably know this by now: I am a big fan of breastfeeding because it’s worked quite well for my son and for me over the past 20 months.

But do I think “breast is best”? No. Breastfeeding worked for us because I have a very supportive husband who could travel with us when I had to, I could manage to sleep while breastfeeding, and I worked from home, so I could type away while Lorenzo fed.

But what about those women who have to go back to work just after giving birth, maybe after a C-section? Is breast best for them? And those who can’t breastfeed? And adoptive parents, or gay fathers?

Formula is best for them in many occasions, just as it can be great for a woman who can sleep more as her partner feeds the baby at night.

Breast is best only if you have the right support, and if it works for you.

Breaking down myths for more freedom of choice

Assessing the real value (it’s not free) and effort (it’s not easy!) of breastfeeding will help us recognise how much work breastfeeding actually involves and create policies that respect breastfeeding as a proper occupation. Think of maternity leave, for example: how can a government like the United States recommend exclusive breastfeeding for six months and not implement a law whereby women can get paid leave to do so?

Also, making sure we don’t repeat unfounded claims (breastfeeding has an expiry date, or lowers the IQ, or it is simply best) and we know all the pros and cons of breastfeeding might help us feel more secure in our choices. This is a conversation that we all need to have: for so many women, a lot of the pressure comes from the cultural norms and expectations. For example, my mother and her generation think I am spoiling Lorenzo by breastfeeding him at this age. Thankfully, I have read enough about extended breastfeeding to feel convinced about my choice, but it would be a shame if I felt forced to hide or stop altogether because of this pressure.

When it comes to breastfeeding, I’m done with stigmatising people.

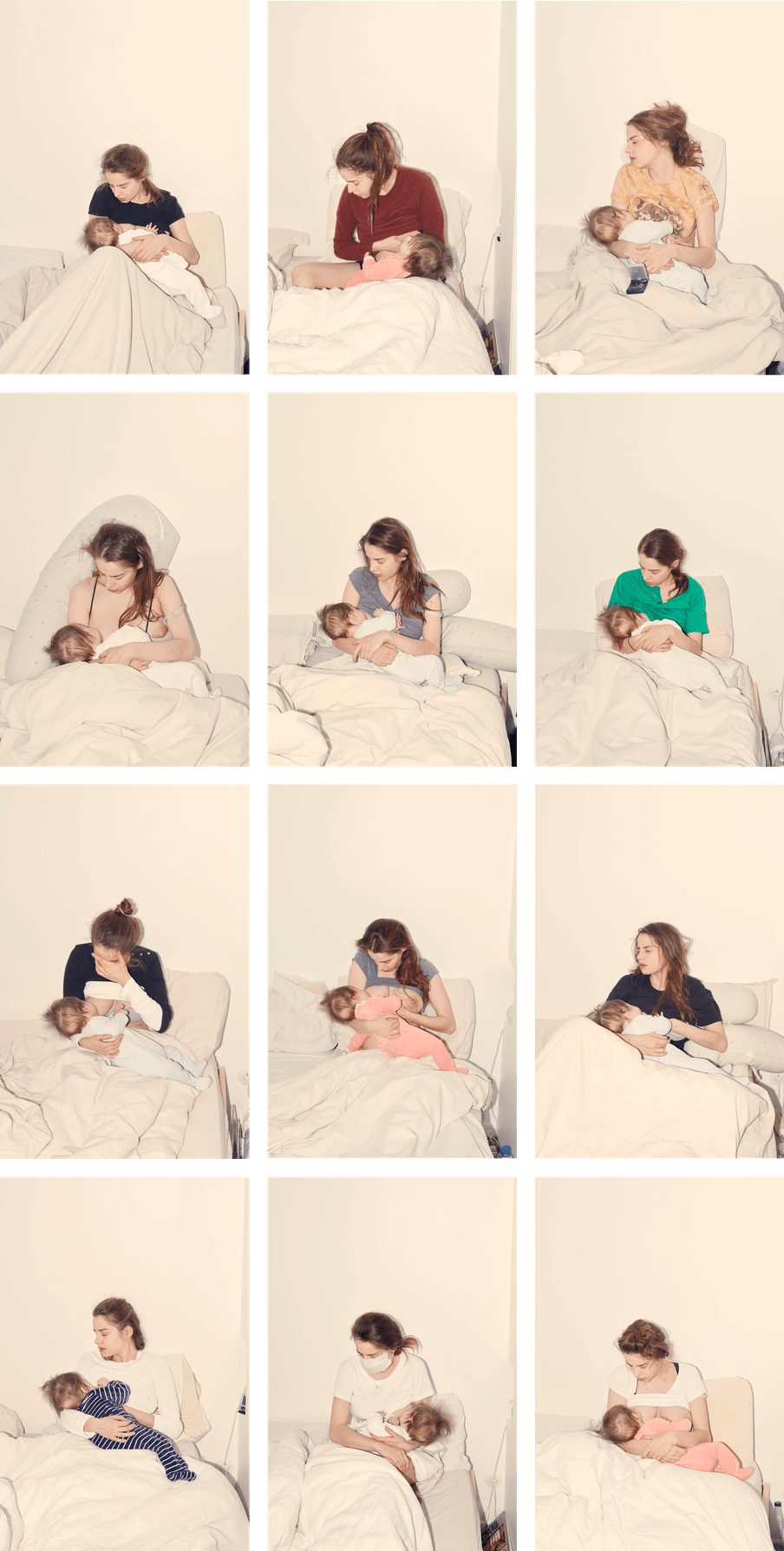

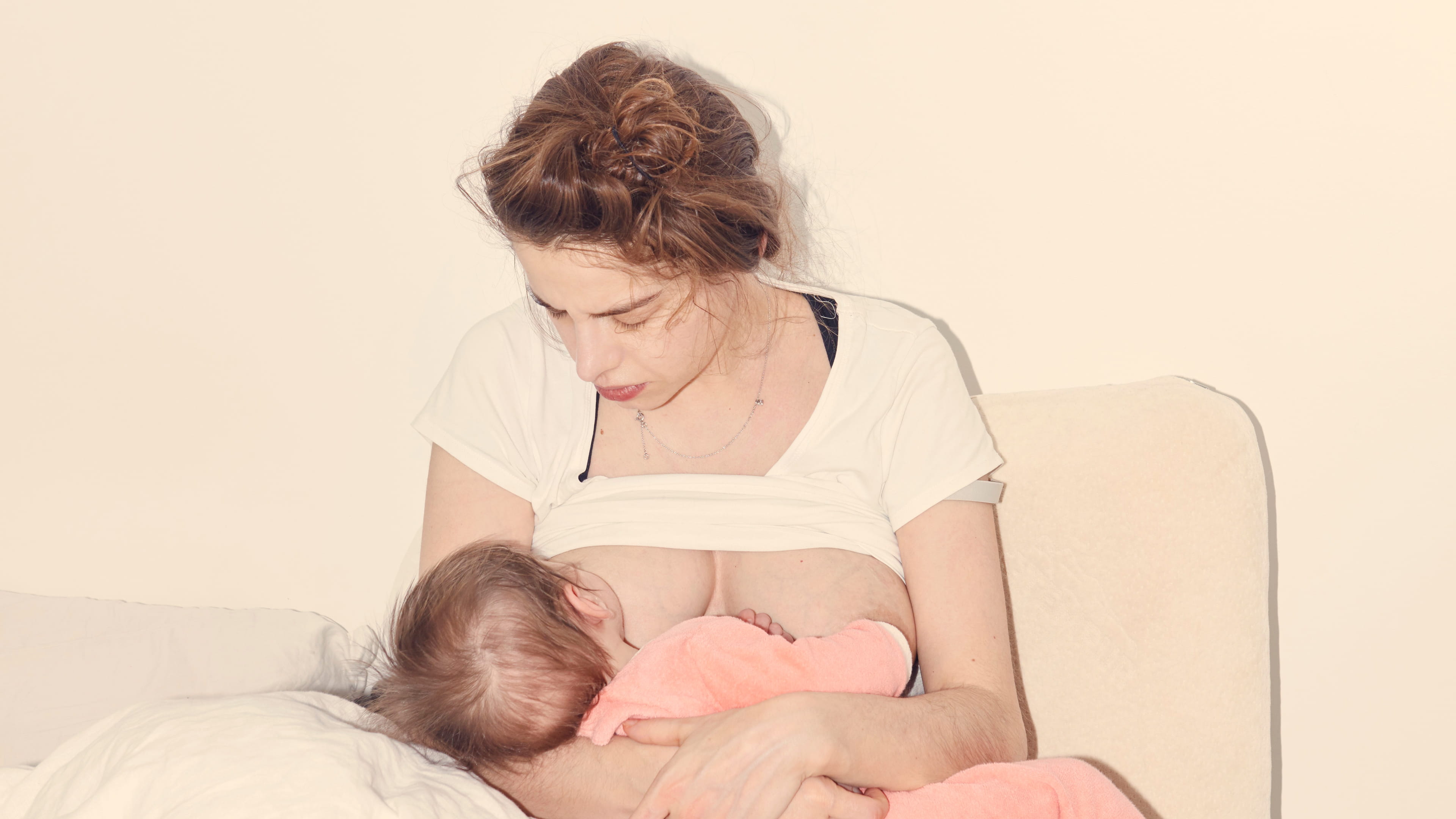

About the images

She is holding the baby with both arms with her head turned to the side; a sleeping madonna. The sight of this woman nursing her child reminds me of all the classic paintings depicting the same event. Only this picture is followed by many almost similar moments alternated with unpolished scenes from the life of a new mom. It shows the hard labour that goes into feeding, the many hours spent on holding, pumping while not sleeping.

About the images

She is holding the baby with both arms with her head turned to the side; a sleeping madonna. The sight of this woman nursing her child reminds me of all the classic paintings depicting the same event. Only this picture is followed by many almost similar moments alternated with unpolished scenes from the life of a new mom. It shows the hard labour that goes into feeding, the many hours spent on holding, pumping while not sleeping. Although these captured moments of his wife nursing are particularly intimate, the distance is palpable. French photographer Vincent Ferrane documented the repetitive act of nursing between his wife and their newborn for over six months. It resulted in the book Milky Way. As an observer, he grasped the opportunity to stay away from a romanticised cliche. (Yara van der Velden, image editor)

Dig deeper

Human milk is the first intelligent superfood. We need to know the science of this medicinal marvel

From added insulation on cold days to extra antibodies during illness, breast milk is customised for every baby. If science will just tell us how, we could argue less about formula and breast pumps.

Human milk is the first intelligent superfood. We need to know the science of this medicinal marvel

From added insulation on cold days to extra antibodies during illness, breast milk is customised for every baby. If science will just tell us how, we could argue less about formula and breast pumps.

Want to stay up to date?

If you’re interested in reading more about breastfeeding, early childhood, as well as reproductive rights and sexuality, you can subscribe to my weekly newsletter about the First 1,000 Days of life.

Want to stay up to date?

If you’re interested in reading more about breastfeeding, early childhood, as well as reproductive rights and sexuality, you can subscribe to my weekly newsletter about the First 1,000 Days of life.