Bilal Nasim is looking forward to his journey into the underworld. “It sounds awful, so I’d love to do it,” he says with a smile.

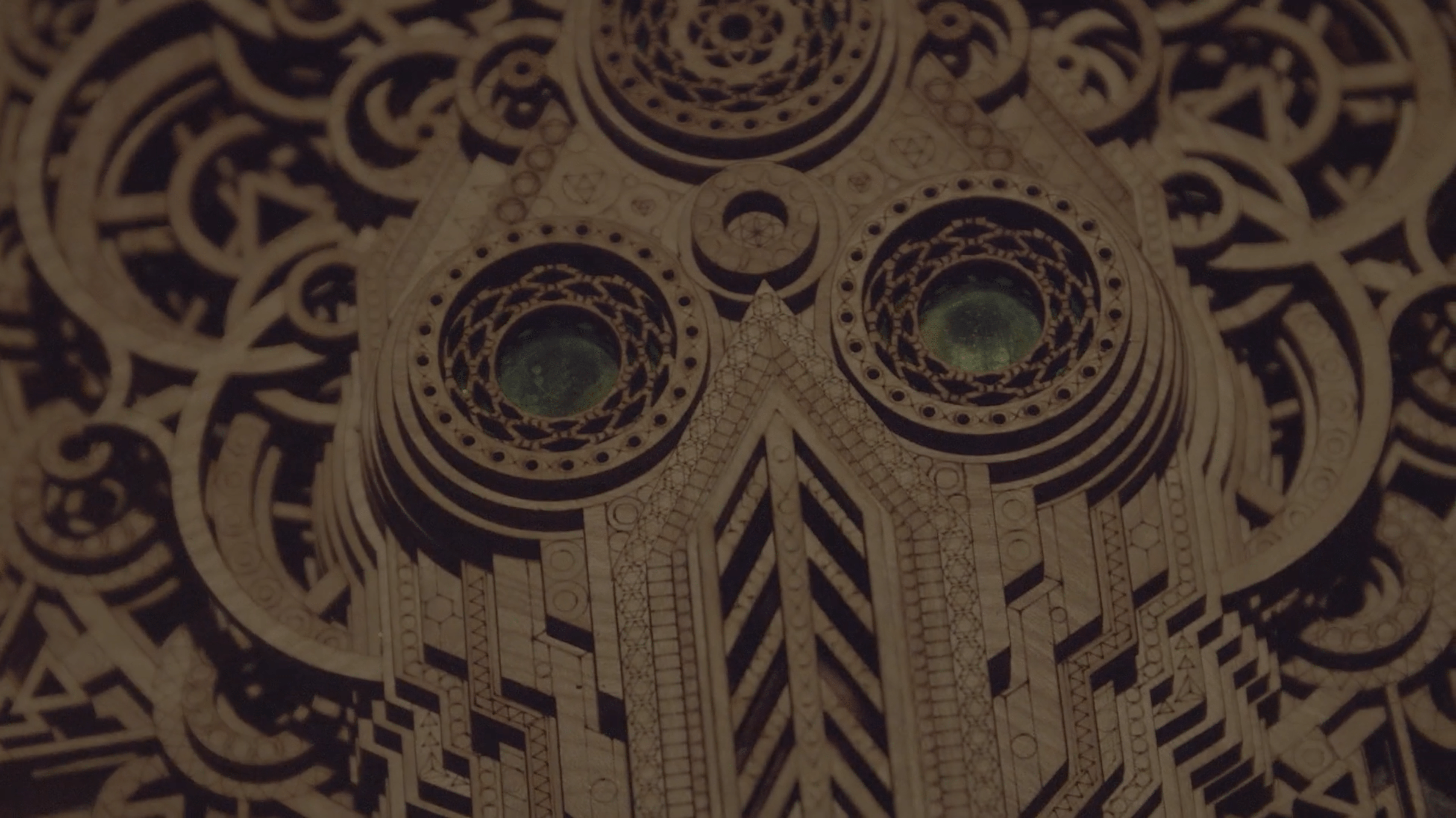

Here’s how it’ll work: a group of intrepid travellers, dressed in garments traditionally worn by the dead, will meet at dusk on the edge of a river in the countryside meant to represent the River Styx, which, in Greek mythology, divides the world of the living from the dead. There they will be met by Charon, the ferryman to the underworld. After paying one coin, they’ll be rowed to the other side of the river where their coffins lie ready to be placed into freshly dug ditches in the ground. When night falls, each member of the small group will lie in their wooden casket which will then be closed and covered with dirt for a number of minutes.

As Nasim, who is a trainee death doula, describes the process, I literally grip the edge of my desk in terror. To me it all sounds like the stuff nightmares are made of. Yet it is precisely that visceral reaction of fear and revulsion that the London-born 36-year-old, who is of Pakistani parentage and Kashmiri ancestry, finds so necessary to explore. “[The act of burial] speaks so directly to our aversion to death and to sensations and instincts which we can spend our whole lives trying to push away,” he says.

Though unconventional, this secular ceremony entitled The Odyssey of the Dead reveals two things: the first, perfectly captured by my own reaction to talk of the underworld, is just how uncomfortable western society is with death. The second is how much our cultures frame grieving as a temporary inconvenience – better suppressed and if that’s not possible, dealt with quickly and decisively.

But confronted, as we have been, with loss of life at an unparalleled scale during the pandemic, what can people who are willing to lean into the concept of death, as Nasim is, teach us about what it means to live? Equally, given that in part the cultural reticence to confronting death in the west may be linked to our desire to forestall grief, how do we begin to better embrace this most crucial of emotions?

Responding to traumatic grief

In March of this year, these questions moved out of the fringes and into mainstream public conversation, as the world watched in horror the scenes unfolding in Bergamo. Military vehicles ferried the bodies of people who had died from the coronavirus in the northern Italian city to graveyards in churches where the pews had been replaced with rows of coffins.

Covid-19 had spread out of China and across the world and Italy was the new epicentre, registering 919 deaths a day at its peak. As governments scrambled to respond, the death toll began to drop in southern Europe and rise elsewhere: the UK, Brazil, the US. With large gatherings no longer permitted, Zoom funerals have become the way people have said goodbye to their loved ones.

Interestingly, it was not a bereavement but the end of a long-term relationship that prompted Nasim to reflect on his own relationship with death. Yet what he describes is familiar to anyone who has known the loss of a loved one. He talks of a “hollow, helpless hopelessness”, before adding what is perhaps an uncommon response to these emotions: “These feelings, this bodily sensation that may be deeply painful, was so ferocious, I just couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t understand where it was coming from.”

In an attempt to understand and integrate this profoundly unsettling experience, Nasim turned once again to the 1973 book, The Denial of Death, written by the US anthropologist Ernest Becker, which he’d first read at university when a terrifying dream led him to begin exploring his fear of death.

The book’s central idea is summarised as follows: “Human beings are mortal, and we know it. Our sense of vulnerability and mortality gives rise to a basic anxiety, even a terror, about our situation. So we devise all sorts of strategies to escape awareness of our mortality and vulnerability, as well as our anxious awareness of it. This psychological denial of death … is one of the most basic drives in individual behaviour, and is reflected throughout human culture.”

The way this denial of death manifests in culture is further explained by the terror management theory, which developed out of Becker’s work, and suggests that we as human beings manage our existential dread by creating cultures and norms that give meaning and value to our fleeting lives.

Our inability to tolerate the anxiety that emerges at thoughts surrounding the impermanence of our existence leads us to attach great importance to things that are ultimately meaningless to grasp at immortality. In your day-to-day life, this false sense of control could look like seeking fame, conspicuous consumption, equating work with existential value or basing one’s worth on romantic relationships.

As Nasim came to understand through his breakup experience, we human beings have a tendency to externalise our self-worth, such that when these things, situations or people are removed or fall away we are left holding an empty bucket. “I put so much of my self-worth into this partnership, which was a wonderful space, that when that was taken away, it became painfully apparent that I actually hadn’t really cultivated any internal self-esteem that I could stand on in that moment.”

Do not keep calm, do not carry on

Marked as our lives have been in recent times by both loss and the total absence of certainty, the stories that neoliberal societies have told themselves about our perpetual progress – that we are always improving and moving forward – are hard to believe in the current context. Yet, collectively, we seem to lack the tools and techniques to deal with the immense loss and change we’re experiencing, particularly in the west.

“When we experience losses in life, when things change, there is a need to grieve. But culturally we don’t have those tools and techniques anymore in a western context so it just builds up,” says Camille Barton an artist, writer and somatic educator of British, Guyanese and Nigerian heritage who is currently researching grief. A recurring theme that emerges in her research is that people in the west often don’t feel as though they have permission or the safety to lose control and actually surrender to their grief, choosing instead to maintain “a stiff upper lip”.

The frenzy of modern life stops us from fully processing the heaviness that is accumulating in our bodies

Some people do turn to talk therapy, but despite its merits, talk therapy doesn’t work across all cultures and remains accessible and affordable for only a small elite even in the west. In the UK, police are dealing with soaring numbers of incidents involving mental health crises, indicating a system already under strain. Limitations of traditional mental health provisioning are replicated beyond national borders as Canadian journalist Anne Thériault’s recent piece for The Correspondent indicates.

Additionally, therapy sees the problem as residing solely in the mind, while other approaches to grief and loss describe it as accumulating in our bodies, and can be physically purged. This is where ritual comes in. Barton explains: “What you see in a lot of indigenous contexts is that their grief rituals are physical experiences. People are screaming, shaking, crying and acting in ways I guess would be labelled as hysterical in the British context.”

These physical acts are not just performative, they help emotion and energy move through the body in order to be released. But these sorts of grief rituals, where we allow ourselves the time for whatever we are feeling to come to the fore, require us to slow down, and here’s the rub: the idea of slowing down runs counter to how we are so often encouraged to live our lives. Productive lives are about running from task to task, thinking and then doing, finding value in being busy. But the frenzy of modern life stops us from fully processing the heaviness that is accumulating in our bodies.

The art of grief-tending

This work cannot be done solely by the individual experiencing grief. There is a communal aspect which Barton describes as our ability to become “comfortable with people losing control and being in altered states that are associated with deep grief." This she refers to as “grief-tending”.

Forging connections with others – especially in scenarios where physical connection is a challenge – is key. In his book Ritual: Power, Healing and Community, writer and teacher of west African spirituality, Malidoma Patrice Somé explains that without community we cannot be ourselves. The community is where we draw the strength needed to effect changes inside of us, a space of interdependence where we can find supportive presence. “What one acknowledges in the formation of the community is the possibility of doing together what it is impossible to do alone.”

To the notion that we might bury our grief deep and hope that time alone will heal, nature provides the answer: the pattern will be cyclical rather than linear. Or as Nasim puts it: “Unless we address it, it’s just always going to distort and come back.”

The whole premise of grief-tending is to go towards that feeling, rather than go away from it. When we emerge on the other side, we realise that we haven’t been torn apart, which is a fear we often have. We think to ourselves when faced with the prospect of confronting our grief “I’ll never be able to put myself back together”, but then we realise that’s not true.

As Nasim knows the experience of the burial ritual will show, when we come back from the place of our dread, some of that weight has been lifted and the energy you may have been holding onto has been shifted. “Through ritual, I want to find safe containers in which to go into my terror, to realise that I’m still here to feel the peace that comes after going through that process.”

These rituals, whether they involve a physical act of burial, or they encourage those who grieve to thrash around screaming, may seem eccentric or foreign, but the logic remains sound and applicable in other contexts in which we face pain and uncertainty. To live lives not crippled by our fears or grief, we must be willing to face them, and ritual helps us do so.

Yet fundamentally, what might be far harder to accept in the west – and beyond as its cultural reach continues to grow – is not these practices themselves but the importance of making the time for them in our otherwise busy lives. As Somé writes: “We run from these symptoms and their sources that are not nice to look at. To be able to face our fears, we must remember how to perform ritual. To remember how to perform ritual, we must slow down.”

At the time of writing, there have been over one million people who have died from coronavirus with little indication that rate is slowing. It is likely that this figure may just be the tip of the iceberg given the hunger and social and economic unrest that will follow.

What at the start of this pandemic may have seemed like nature sending humanity to the naughty corner for a short while has now been replaced with the realisation that the very classroom we imagined ourselves to be standing in no longer exists.

Our ability to both acknowledge and lean into the intense grief triggered by the pandemic as a collective rite of passage – in which much that we assumed was certain to our sense of being is stripped away – may be the very act that enables us to level up at the individual, community and societal level in ways that are more connected, more compassionate and more kind.

Dig deeper

No justice, no profits: the fight for racial equality isn’t just in the streets. It’s in the boardroom too

Some big brands have been quick to voice support for Black Lives Matter, but that’s no longer enough. In multiple industries, pioneers are seeking change from the inside out.

No justice, no profits: the fight for racial equality isn’t just in the streets. It’s in the boardroom too

Some big brands have been quick to voice support for Black Lives Matter, but that’s no longer enough. In multiple industries, pioneers are seeking change from the inside out.

Our world is built for profit. Let’s build one that protects us instead

We live in a society where it’s easier to get a Michelin-star meal delivered to our doorstep than it is to get a medical mask that protects our nurses and doctors. And it’s designed that way. But we can change it for the better, just as we can change ourselves.

Our world is built for profit. Let’s build one that protects us instead

We live in a society where it’s easier to get a Michelin-star meal delivered to our doorstep than it is to get a medical mask that protects our nurses and doctors. And it’s designed that way. But we can change it for the better, just as we can change ourselves.