"The trouble with the Dutch is they are so self-effacing, so modest, that they’ve stopped believing their own history."

– Johan van Veen (1893-1959)

There is a story that needs to be told, and it needs to be told now. It is the story of Johan van Veen. Engineer. Father of the Delta Works. One of the greatest men in Dutch history.

And yet, his name is virtually unknown.

In the village of Uithuizermeeden in the northern Dutch province of Groningen stands a small monument in Johan’s honour. A grey bust bearing little resemblance to the man himself, erected between a car park and a supermarket ("one of the ugliest spots in the Netherlands", according to his biographer).

Johan van Veen called himself "Dr Cassandra", after the Greek princess whose warnings of Troy’s destruction went unheeded. As an engineer at the Netherlands’ Directorate-General for Public Works and Water Management (Rijkswaterstaat), Johan predicted the devastating North Sea flood of 1953. Not once, but repeatedly, for 20 long years. "Yes, that can happen in Holland," he told a reporter for the weekly Elsevier in 1952. "Because people just don’t get it." Dismissing him as a panic-monger, the magazine editor scrapped the whole interview.

Johan’s story is the story of Holland. It’s the story of a small nation on the North Sea that by rights should be deep beneath the waves. A nation that frowns down on high-achievers and has elevated rudeness to a virtue. A nation of shopkeepers who go around quibbling and complaining, grumbling and groaning, insisting up and down that they won’t, they can’t and they mustn’t, right up until they unexpectedly pull off the impossible.

But disaster has to strike first.

On 31 January 1953, the national weather agency forecast is "overcast with rain, heavy south-southwesterly wind with occasional strong gusts". Nothing unusual.

It’s just another winter’s day – a day to stay indoors. All across the Netherlands, families huddle around wood stoves and tune into De Familie Doorsnee ("An ordinary family"), a popular radio serial. It’s cosy, too, at the village pub in Nieuwerkerk aan den IJssel, just a few miles north-east of Rotterdam, which is abuzz inside with locals laughing, drinking, dancing. All of a sudden, a man bursts through the door.

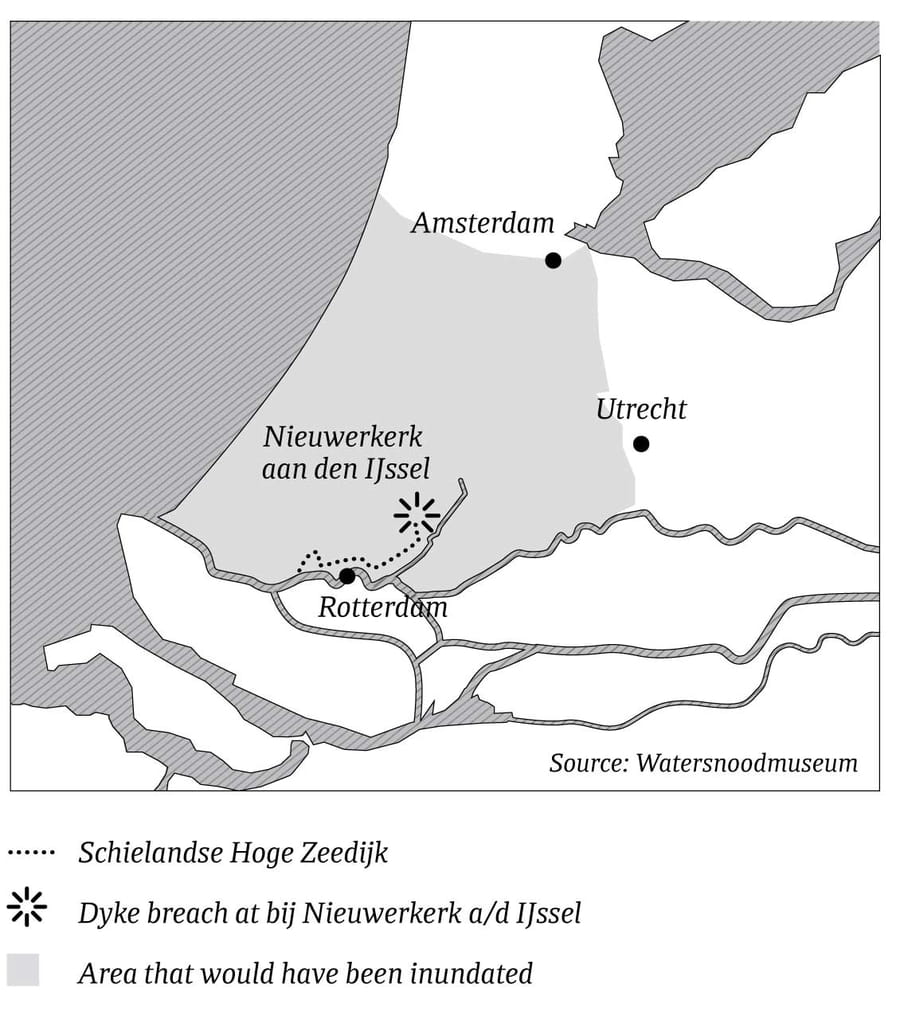

It’s the river. The river is too high. Nieuwerkerk sits in a polder – an area of land reclaimed from the sea – along a branch of the IJssel river. Separating it from the river is a high dyke called the Schielands Hoge Zeedijk, which has protected the polder’s inhabitants for centuries. The polder is nearly seven metres below sea level, and Nieuwerkerk is at the very lowest point in the Netherlands. Beyond it lies a densely populated region stretching from Gouda to The Hague, from Rotterdam to Leiden. A region that’s home to more than three million people.

If the dyke at Nieuwerkerk fails, half of Holland will drown.

Realising there’s not a moment to lose, the village mayor Jaap Vogelaar gives orders to sound the alarm and for everyone at the pub to start hauling sand bags. He himself rushes into the darkness, shouting at spots along the river where the dyke needs to be reinforced. Dozens of men arrive, but as soon as they feel the ground give way beneath their boots, see the water cresting over the dyke and realise it could collapse at any moment, many turn and run.

All the while, the water continues to rise. Rain, sleet and hail pour from the sky. A cutting northwesterly wind sends waves surging against the slope. Here and there, whole sections of the inner dyke wash away.

And then it happens. At 5.30am, Mr Kleijbeuker, a machinist, sees an entire length of dyke give way, leaving a gaping hole 15 metres wide. Water rushes in through the gap and floods down into the deep polder, heading straight for the metropolitan heart of Holland.

At that moment, Captain Arie Evegroen is aboard his barge the Two Brothers. He moored at Nieuwerkerk earlier that evening, hoping it would be safe. But suddenly the mayor appears beside his boat. Shouting to be heard above the storm, he directs Evegroen to steer his 18-metre barge into the dyke. He wants the captain to plug the hole.

Horrified, Evegroen refuses. It doesn’t take much imagination to picture his boat – with him on it – taking a nosedive into the polder. But the mayor is determined. He commandeers the boat "in the name of the Queen". The captain gives in.

As plans go, it’s a long shot.

"Trying to close a burst dyke with a boat is the kind of stunt that would fail 99 times out of 100," the district water board engineer will say later. But in the moment, there’s no time for consideration. Evegroen navigates into the raging river and positions his bow perpendicular to the dyke. Then, propeller turning, he starts to pivot towards the gap. The boat swings in like a floodgate, closer and closer, until the powerful current sucks it right into the dyke. You’d almost think the Two Brothers was made for this purpose – just a tiny bit shorter and it wouldn’t have worked.

Even the captain can hardly believe it; just like that, the hole in the dyke is plugged. Arie Evegroen will go down in Dutch history as "the saviour of Holland" – albeit a reluctant one. "My barge was there," he says afterwards, "and there was nobody else to do it."

In the early hours of 1 February 1953, the dykes protecting Holland broke in more than 500 places. Over 1,290 sq km of the country were flooded, including almost the whole province of Zeeland. Thousands of homes and farms were destroyed, 100,000 people had to be evacuated and 1,836 died.

But it could have been much worse.

On that first day of February the spring tide was low, wind speeds were unexceptional and the water level in the Rhine and the Meuse rivers wasn’t particularly high. "At that time of year the water should have been at least a metre higher," noted the Elsevier journalist whose 1952 interview with Johan van Veen never ran. "In that case, it would have flooded everywhere." Instead, the rivers had absorbed much of the sea surge.

Over at the Directorate-General for Public Works and Water Management, Johan investigated what would have happened had Captain Evegroen failed. Answer: the hole in the Schielands Hoge Zeedijk would have torn wide open, making the breach impossible to close. Within a week, most of the province of Zuid-Holland – the lowest-lying part of the country – would have been under water. After 26 days, the sea would have been lapping at the fringes of Amsterdam.

"The flood, the flood! I can neither think of nor do anything else," Johan wrote to a British friend some weeks after the disaster. "I know how close the whole of the Netherlands came to absolute ruin. Not a camel, but a whole herd of elephants passed through the eye of the needle. Frankly, it’s unbelievable the middle of the country still exists."

Climate change is something that tends to feel abstract. So the planet will be four degrees warmer in 2100 – is that a bad thing? It doesn’t sound all that terrible. And if the sea level goes up three metres, so what? It doesn’t feel like much.

So let me make the threat more concrete.

The very existence of the Netherlands is at stake.

There’s a possibility our children will have to abandon cities like The Hague and Delft, Rotterdam and Amsterdam, Leiden and Haarlem. That centuries of culture, heritage and history will be lost. That’s not what I say – that’s what the scientific successors of the engineer Johan van Veen say. Reading their work, you don’t have to look far for a Dr Cassandra. In fact, these days, there’s a whole legion of Cassandras.

For this story I interviewed seven Dutch scientists, all sea level experts. And I was shocked at how candidly they describe scenarios in which the Netherlands will be forced to sacrifice vast areas of its land to the sea.

"Say you start having kids now," says Dr Maarten Kleinhans, a professor of physical geography at Utrecht University, "then you’re talking about people who could lose their homeland, who won’t be Netherlanders, because the Netherlands will be gone. That’s what’s at stake here."

Dr Kim Cohen, assistant professor of geography at Utrecht, shares this fear. "I think this country can cope with a sea-level rise of two metres. But three, four, or five metres? That’s doubtful. The measures needed would be draconian. At that point, I think we’d start sacrificing cities."

For a long time, it was assumed the sea level around the Netherlands would rise at most 85cm by the year 2100. But in recent years that figure has crept up steadily. Where 10 years ago the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) was still calculating in decimetres (tenths of a metre), now it’s talking whole metres. If the world doesn’t cut greenhouse gas emissions fast enough, the Netherlands will face a sea-level rise approaching three metres by 2100. And a hundred years after that, five to eight metres.

"It’s really terrifying," says Maarten Kleinhans. "Well and truly terrifying. Without trying to match myself with him, I feel pushed to shoulder Van Veen’s role as Dr Cassandra. I’m noticing a sense of despair among colleagues in the field, especially polar ice researchers. For years we’ve all been saying this is happening, and the world still won’t listen properly."

‘For years we’ve all been saying this is happening, and the world still won’t listen properly’

One of those polar ice researchers is Michiel van den Broeke, professor of polar meteorology at Utrecht University. When I repeat Kleinhans’s words to him, the line goes quiet briefly. Then: "Look, Maarten’s a great colleague. But he’s also very vocal. I’ve promised myself not to go along with the chorus of people saying ‘We’re not being heard, nothing’s being done’. You’ve got to keep the roles of science and policymaking separate."

In June 2018, Van den Broeke co-authored a groundbreaking article published in the journal Nature revealing that the south pole ice sheet is melting faster than previously thought. In the past decade, as much as three times faster.

That’s bad news for the Netherlands. Melting land ice not only equals higher sea levels, but as it warms water also expands. What is more, if ice at the south pole melts, the Netherlands is at particularly high risk.

That’s because right now the gravity of the miles-thick ice cap attracts gigantic quantities of water. This gravitational force is so powerful that the water actually slopes upward against the ice, like a vast mountain of water. But now that this ice sheet is melting the gravitational force is diminishing, so water at the south pole is subsiding and, like a seesaw, the ocean at the north end of the earth is lifting up.

The north end: that’s us.

Van den Broeke stresses that the scientific models have a large margin of uncertainty, especially when it comes to the speed of future sea-level rises. But the risks are big too. Roderik van de Wal, professor of sea-level change and coastal impacts in Utrecht, is most worried about the tipping points. Specifically, the point when glaciers at the south pole become so destabilised that the melting can no longer be stopped, no matter what we do. "We don’t know precisely where those points lie, but it could be as soon as in the next 20 years."

Once a tipping point is reached, the ensuing sea-level rise will be measurable in whole metres. That much is certain. Kim Cohen, the geographer, drew a map of what the Netherlands would look like in 2300 if we lose this war against the water.

When I saw this map for the first time, I was reminded of something Johan van Veen once said. "There will come a day when, with a sigh of relief, we’ll sacrifice this country to the waves."

The man who called himself Dr Cassandra had always been a loner.

At university, he refused to join any of the student societies. He had few friends and went around in wrinkled shirts and threadbare jackets. One time – by then he was working at the directorate – he arrived at the office looking distracted. "Mr van Veen," a colleague cried out. "You haven’t any socks on!"

It was when he was by himself on the water, doing research, that Johan was truly in his element. "Search and measure" was his motto. For his thesis, he walked the whole length of the English coastline near Kent, interviewing 50 locals along the way ("harbourmasters, fishermen, lighthouse keepers, old folks"). That’s how he discovered the South Foreland Lighthouse stood a good 10 metres closer to the cliff edge than it had in 1793.

As head of the directorate’s research department, Johan worked incessantly. Evenings. Nights. Weekends. Which is not to say his superiors were pleased with him. Besides a stiff disposition Johan had a problem with authority – and that’s putting it mildly. During the Nazi occupation he had amused himself by taking out his motorsailer, sporting patriotically orange curtains, and sailing it back and forth in front of German troops for fun. At lunch, he made a big production of displaying his equally bright orange crockery on deck.

Tact and diplomacy were wholly wasted on Johan. He did not suffer fools gladly, which in his view was almost everyone. Once, during a conference, he sneered at the director-general, his boss: "Sir, you so thoroughly don’t understand anything about it that I can’t possibly answer you."

In June 1946, Johan brought that same boss a thick report on the poor state of the dykes in Zeeland. Wordlessly the director took it, went to a cupboard, put it inside, locked the door and told Johan to sod off. (In January 1948, Johan mentioned this incident to his doctor. "I wanted to ask him," he later wrote in his journal, "if he could give the director-general some poison, as that would have been most helpful to me.")

Outside the Netherlands, however, Johan enjoyed a growing reputation. His reports were widely read and hydraulic engineers came to The Hague from all over the world simply to speak to him. But at home, Johan had few fans. Mostly, he was dismissed as an alarmist. Even by the Dutch Water Management Secretary, who in response to parliamentary questions around this time wrote: " … No one need worry about the question [ … ] whether they shall wake up one day to see the water level has risen above the dykes."

In reality, the situation was becoming increasingly dire. Already in a state of disrepair, the dykes had been further damaged by Allied bombings during the second world war. Efforts were made to patch them up in places, but responsibility for water management was fragmented across 263 separate bodies. Moreover, many of the water districts were underfunded, plus the bureaucracy was maddening – inspiring Johan to pen this satirical verse:

"Lord, give us that we shall come to no decisions this day, and bring us no responsibilities, but lead us so that by all our acts and omissions wholly new and utterly unnecessary agencies will be created."

All this time, Dr Cassandra continued to warn that far more extensive measures were needed to protect the Netherlands from the next storm surge. And that another storm surge was sure to strike – the only question was when.

Johan even drafted an ambitious plan during these years proposing massive dams to close the mouths of the country’s rivers. Dams on a scale the world had never seen. The result, a veritable Delta Plan, was lying on the secretary of transport and water management Jacob Algera’s desk on 29 January 1953.

48 hours later, the dykes broke.

How was it that Johan saw what nobody else did?

One factor undoubtedly helped. He knew his history. The engineer was well aware that the Netherlands had suffered countless storm surges in the past. On average, 16 per century. Such as, back in 1170, when the water tore across the dunes at Den Helder and ripped Texel island off the Dutch mainland. And the All Saints’ Flood of 1570, which left at least 20,000 people dead and washed away half the coastal village of Egmond aan Zee. Or the flood of 1808, after which King Louis Bonaparte wondered if saving the province of Zeeland was really worth the expense.

Johan was well acquainted with the history of Holland’s age-old struggle against the sea. He knew it was no coincidence that the country’s oldest political bodies were its water boards, presided over by its earliest administrators, the dyke reeves. That the Dutch had invented polder windmills to drain the land in the 15th century; and built the mill complex at Kinderdijk in the 18th century, with 20 windmills to pump 50,000 litres of water every minute.

In time, the Dutch drained a grand total of 4,000 polders, creating a country of which one quarter lies under sea level. In 1916, after yet another storm surge, the Afsluitdijk ("enclosure dyke") was built, a 32km dam that still protects the northern half of the country against the North Sea.

But Johan also knew the Dutch are forgetful.

The longer the sea kept quiet, the louder the old objections: Won’t. Can’t. Mustn’t. "The trouble with the Dutch," Johan wrote, "is they are so self-effacing, so modest, that they’ve stopped believing their own history."

But after 1 February 1953, everything changed.

In the months following the disaster, the breached dykes couldn’t be sealed fast enough. When the last one was repaired at Ouwerkerk on 6 November, people all across the country hung out their flags in celebration. There was a great sense of unity – and no interest in laying blame (in fact, it was widely believed to have been the will of God). But people did realise that Johan van Veen had been right all along. Everywhere he went, they whispered: "Did you know he’s called Dr Cassandra?"

Suddenly, the whole country wanted to know all about the megalomaniacal plan Johan had offered the state secretary just two days before the flood. Abruptly, the won’ts and the can’ts and the mustn’ts fell silent, and the Netherlands embarked on the largest infrastructural project in its entire history.

When the plan for the Delta Works was ratified by the Dutch House of Representatives on 5 November 1957, construction had already started. Foreign journalists were astonished at the country’s determination. "What those crazy engineers now represent," wrote The Saturday Evening Post, "is a Maginot line of three new dams [ ... ]. This concept has been around for a while. But, as one Dutchman said, ‘We first had to get angry to forget that it was impossible.’"

Headline of that article? "The Dutch Strike Back Against the Sea."

The cost of the Delta Works was budgeted in 1958 at 3.3bn guilders, amounting to 20% of the country’s gross domestic product at the time (about €140bn in today’s money). But it wound up costing quite a lot more. This owed to controversy which arose in the 1960s over the plan to close off the Eastern Scheldt estuary. Environmentalists feared for the fish, while fishermen feared for their jobs. In the end, all sides sat down together to achieve a consensus for the greater good – following a decision-making model and proud Dutch problem-solving tradition aptly known as "poldering". This ultimately led the Eastern Scheldt storm surge barrier to be redesigned with huge sluice gates that would close only when needed, representing an unprecedented (and very pricey) feat of engineering.

Where the Netherlands had been considered stodgy and old-fashioned right up through the 50s, now those days were well and truly past. "The Dutch have stopped being dull," a British journalist wrote in 1967 of the land of football legend Johan Cruyff, the anarchist "Provo" movement and the monumental Delta Works. Johan van Veen was proclaimed "master of the floods", and US engineers even hailed the Dutch Delta Works as one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World.

But at home Johan van Veen was as unpopular as ever. The fact is, we Dutch don’t care much for heroes. Few things are as suspicious to us as success. If you can’t help being a high-achiever, at least do everyone a favour and keep it to yourself.

That was fine with Johan. He didn’t like effusive compliments. And he didn’t trust foreign journalists. What did they know about Dutch history?

The Delta Works themselves – not surprisingly – manifested that same Dutch no-nonsense pragmatism. The service buildings were functional grey blocks. Where US Americans would have erected grandiose monuments and the French would have inscribed them with solemn mottos, the Dutch left it at water, wind and concrete.

And then promptly forgot all about their wonder of the world.

These days, it’s mostly foreign tourists who marvel at the Eastern Scheldt barrier with its 65 pillars, each as big as a cathedral, and at the Maeslant barrier with its two swinging Eiffel towers and biggest ball joints in the world. The Dutch themselves are less interested. At the Haringvliet dam, with its 17 sluices, the information signs are worn and weathered, the letters falling off. And the artificial island of Neeltje Jans, made to aid construction of the Eastern Scheldt barrier, is now home to a fun park owned by a Spanish multinational.

And what about the father of the Delta Works, Johan van Veen? He too is all but forgotten. Not a single dam, bridge or dyke was ever named in his honour. The cabinet containing his life’s work long stood collecting dust at the directorate, but has since been thrown away. "That cabinet held the history of the Delta Works," says Willem van der Ham, author of an impressive biography about the engineer. "It was national heritage, but it’s gone now."

Meanwhile, the sea level is rising.

According to the Dutch meteorological institute, even if every country in the world fulfils its commitments and we manage to limit global warming to 2C – even then the Netherlands could face a sea-level rise of two metres by 2100. And if the planet warms beyond that (to 4C in 2100), we’re almost certain to exceed the two-metre mark, coming out at (in the worst-case scenario) five to eight metres in 2200.

The Delta Works were designed to accommodate a rise of only 40 centimetres.

Even if we manage to limit global warming to 2C – even then the Netherlands could face a sea-level rise of two metres by 2100

So the Netherlands is facing a challenge that’s unprecedented in scale. At present almost 70% of the population live in flood-prone areas, and that percentage is only growing. The densest part of the country around the major cities in the west, home to over eight million people, is like a giant bathtub, sinking a little deeper year by year as the water rises around it.

"According to the current models, it will really start to kick in around 2050," says Marjolijn Haasnoot, a water management researcher. "My kids will be the same age then as I am now. It’s not very far off."

All the experts I talked to think the Netherlands can still cope with a sea that’s two metres higher. That is, provided we take measures so extreme they’ll make the Delta Works look like child’s play. Like building the biggest pumping stations the world has ever seen to drain water from low-lying rivers into the higher-lying sea 24 hours a day, seven days a week. To reinforce the Dutch coastline, a fleet of dredgers would have to be permanently stationed in the North Sea to keep replenishing the shoreline, requiring 25 times as much sand as is already used now.

And that’s just the beginning. If the earth warms more than 2C, sea levels will rise higher and the Dutch will have to think even bigger still. Johan van Veen already imagined a colossal dam stretching from Norway to England. Now there are proposals for a vast seawall going from northern France to Denmark.

Would that work? Well, it depends who you ask.

"We are more likely to grow gills," geographer Maarten Kleinhans responds drily. The Utrecht University professor is among the Cassandras who think it’s game over for Holland if the sea level rises more than two metres. "Only at university engineering departments in places like Delft will you find folks who think we could survive that. The kind who believe in a makeable world."

So I decide to give one of them a call.

Bas Jonkman teaches hydraulic engineering at Delft University of Technology. Turns out, he’s one of the youngest professors there. That’s no accident, he tells me: the older generation is poorly represented in his field. "They mostly went into ICT, project management and banking," says Jonkman. "Those jobs paid more." Where engineers used to dream of building bridges and dams, now they construct complex financial products and the algorithms behind online ads.

In recent times that tide seems to be turning. Jonkman himself is part of a new generation of engineers who are eager to build. "Looking at my students now, most stay in this field."

Talking to Bas Jonkman, it’s hard not to get swept up in his outpouring of plans and ideas. He stresses that there are plenty of options, even if the sea rises more than two metres. For starters, Holland could go on the offence and spray up some islands to break incoming waves. Those islands could then double as wind parks. Or, we could move Schiphol Airport out to sea. If that’s not enough, a huge ring dyke could be built linking all those islands, resulting in an inland sea off Holland’s west coast.

Admittedly, the impact of a plan like this would not be pretty for marine life. (Dutch ecologists are known to say the country has suffered two environmental disasters: the Afsluitdijk and the Delta Works.) But Jonkman isn’t deterred by this criticism. Nature is dynamic and can recover, he says. "I’m used to thinking in solutions, not problems."

But by now at least one thing is clear.

However widely their views differ, ecologists and engineers agree on the big issue. We have to do everything in our power to prevent a sea-level rise exceeding two metres. Whatever the cost. First of all, by eliminating all greenhouse gas emissions as quickly as possible. Not just in Holland, but worldwide. And our new Delta Works will have to go beyond dams and dykes, bridges and islands. A Delta plan for modern times also has to include solar panels and wind parks, mega-batteries and high-speed trains.

This realisation finally seems to be dawning in The Hague. On 28 May 2019 the Dutch senate passed a climate bill pledging to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 49% in the year 2030 relative to 1990. And by at least 95% in 2050.

Is that a lot? Is it fast?

Let me make the challenge more concrete.

The Netherlands has to take eight million buildings off natural gas. To replace nine million cars with electric or hydrogen-powered models. To scale up its power grid times three. To fill a quarter of the North Sea with windmills. To install 75 million solar panels. To plant 1,000 sq km of forest. And on top of that we’ll need a tonne of technologies that have yet to be invented.

In short, we need to embark on a country-wide renovation on the biggest scale ever.

Meanwhile, our nation of shopkeepers is still haggling over the price of this revolution. One party leader has claimed €1,000bn; journalists who check their facts put it closer to €500bn to €700bn. Either way, it’s a jaw-dropping sum. We’re talking 70 to 100% of Holland’s gross domestic product (GDP). That’s five times as high as the Delta Works.

True, many technologies will get cheaper when rolled out on a larger scale. And true, the costs can be spread out over 30 years to an annual price tag of "merely" 3% of GDP (roughly what the whole country spends on holidays per year).

But still, when people start talking about how expensive the energy transition will be, they’re absolutely right. Of course it’s going to be expensive. How could it not be? Not since 1953 has the Netherlands faced a challenge of this magnitude. Now is not the time to pinch pennies.

Among Dutch dyke reeves there’s an old saying: "Give us today our daily bread, and every so often a flood" (of course, it rhymes in Dutch).

And it’s true: it seems we’ve always needed a disaster to shake us up. In 1916 it took the inundation of the northern part of the country to make us build the Afsluitdijk. And in 1953, the south had to be drowning before we embarked on the Delta Works.

So will we wait once more for the worst to happen? For the sea to swallow half the country before we stop grouching about expensive heat pumps and unsightly windmills? Can only a disaster wake us up to the fact that we need to pull off a revolution, transform the entire economy and blaze a trail for the world?

One thing is certain. If we want to hold onto the Netherlands, we – the Dutch people – have to fight for it. We have to fight against the water, but also against ourselves. Against our apathy. Our thriftiness.

Sure, we may be a nation of quibblers and complainers, of grumblers and groaners. A nation that can be wilfully blind, even when the truth has been flashing in front of us for twenty-odd years. (Elsevier magazine, which dismissed Johan van Veen as a panic-monger back in 1952, now talks of "the panic-factory called climate change".)

But we’re also a nation that can rise above itself. That’s capable of incredible feats. Not because we yearn for a pedestal or a statue or to be heroised by future generations. That will never happen in any case – here, you’re lucky to get an ugly bust outside a supermarket.

No, we can do this because we’re a nation that has mastered the art and the politics of poldering. Because we can turn water into land. Because, as we’re so fond of saying, God created the world, but the Dutch created the Netherlands. And because our future, once again, is in our own hands.

Rutger Bregman,

January 2020, Houten (presently still two metres above Amsterdam Ordnance Datum)

- Want to learn more? Follow The Correspondent’s climate coverage here.

Translated from the Dutch by Elizabeth Manton.

Dig deeper

Don’t forget: disasters and crises bring out the best in people

Disasters and crises bring out the best in us. This simple fact is confirmed by more solid evidence than almost any other scientific insight, but we often forget.

Don’t forget: disasters and crises bring out the best in people

Disasters and crises bring out the best in us. This simple fact is confirmed by more solid evidence than almost any other scientific insight, but we often forget.

If we want the future earth we deserve, we need to do things that scare us

We’re at a transformative moment in history – from an old world based on extraction and exploitation to a new world we must create as we go. Embracing discomfort is at the core of climate action. And it’s something we’re all capable of.

If we want the future earth we deserve, we need to do things that scare us

We’re at a transformative moment in history – from an old world based on extraction and exploitation to a new world we must create as we go. Embracing discomfort is at the core of climate action. And it’s something we’re all capable of.