On August 10 and 11, 2016, Ahmed Mansoor got a series of texts on his iPhone. Their subject was a gripping one: new revelations on the torture of prisoners in his homeland, the United Arab Emirates. Mansoor is an internationally renowned human rights activist who was imprisoned in 2011 after calling for democratic reforms in the Gulf state.

Mansoor forwarded the messages to researchers at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab. They discovered that an Israeli company, the NSO Group, was attempting to install malware on his phone. Hacking Mansoor’s device was evidently worth a lot to the UAE’s government: software like this is hugely expensive.

It wasn’t the first time Mansoor had been sent malware. Two European companies, Gamma Group International in Britain and HackingTeam in Italy, had previously tried to break into his computers and phone. Citizen Lab had uncovered those attempted hacks too.

Both companies initially denied wrongdoing – until they were hacked themselves, by an activist calling himself Phineas Fisher. He unearthed internal correspondence showing that each had done business with a number of despotic states. Both firms remain active today.

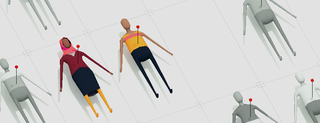

One in three exports is to “not free” countries

Incidents like this spurred the European Union to act to curb the export of surveillance products in 2014. Human rights activists were overjoyed.

But today, the celebrations have given way to disappointment. The new rules haven’t had the effect many had hoped for. Research by our international consortium Security for Sale shows that EU member states permitted exports of cybersurveillance technology at least 317 times in the last three years. They denied only 14 applications.

Almost one third of the licenses were for exports to countries the watchdog organization Freedom House has branded “not free.” Despite the attempts to hack Mansoor, Denmark and the UK have both approved exports of mass Internet surveillance systems to the UAE during the past two years.

Only 17% of permits were for exports to countries Freedom House deems “free”

And Finland has issued several licenses to the Finnish subsidiary of the Canadian company EXFO allowing sales of cellphone spying technology to countries including the UAE.

The UAE isn’t the only country buying surveillance tools from Europe. Egypt – weighed down by General Abdul Fatah Al-Sisi’s repressive regime since 2013 and ranked “not free” by Freedom House – received spy tech exports from the UK.

The British government also permitted the sale of surveillance technology in Vietnam, a communist one-party state ranked as “not free.”

Reporters Without Borders has characterized the country as an “enemy of the Internet” and as the world’s third-largest prison for online dissidents and bloggers after China and Iran. Denmark, meanwhile, allowed a Danish business to demonstrate a system for monitoring Internet traffic in Vietnam.

Of the licenses uncovered in our investigation, 52% were for exports to countries Freedom House ranks as “partially free.” They include Turkey, where president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s government has cracked down on political opposition following a failed coup last year.

Only 17% of permits were for exports to countries Freedom House deems “free.”

Compared to Finland and the UK, the Netherlands hasn’t exported much spy tech. The Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which grants the relevant permits, issued one for the sale of software to Montenegro – considered “partially free” by the Freedom House. But it refused one for export to the UAE. In interviews, the Ministry told us it did so because of human rights concerns.

Why many more applications should be denied

“The data clearly illustrate that the current regulation is insufficient,” says Edin Omanovic, a research officer with the nonprofit group Privacy International. “The very low amount of applications being denied is concerning. Given that many of the countries that these products are being sold to have a problematic human rights record and no legal framework regulating the use of surveillance technologies, a lot more exports should have been refused.”

US security researcher Collin Anderson, who wrote a report on regulating cybersurveillance for the NGO Access Now and has spoken about the subject before the European Parliament, draws a similar conclusion. “The few cases where a denial has been issued are success stories,” he says. ‘But the overall picture seems to be that the good intentions behind the rules have not been followed up in practice.”

Security for Sale’s investigation is the first extensive, systematic probe of the issue. The figures may actually be much higher. Of the 28 EU member states, 11 refused to furnish the information we requested. They include France and Italy, both home to some of the world’s biggest spy-tech businesses.

“There are numbers you’ll never find,” says Marietje Schaake of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe in the European Parliament, who’s been at the forefront of efforts to monitor the digital weapons trade. ‘We’re talking about a very gray, untransparent, and dark industry.”

“We’re talking about a very gray, untransparent, and dark industry”

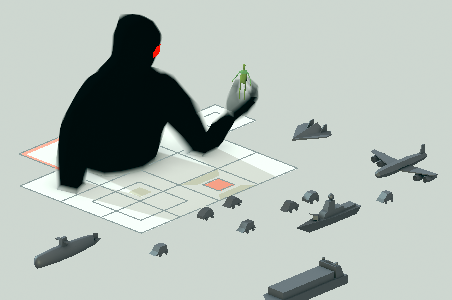

So how do the current rules work? In the EU, national authorities in the member states determine whether or not to grant export licenses for surveillance products, which are so-called dual-use goods, usable for both military and civilian purposes. According to EU regulations, issuers of permits must take into account “all relevant considerations” – including the possibility that a technology could be used to violate human rights.

The rule for dual use technology was added to EU export policies in 2014. Citing “growing security concerns regarding the use of surveillance technology and cyber-tools that could be misused in violation of human rights or against the EU’s security,” the European Commission decided the export of spying tools outside the union would henceforth require government approval.

The European Commission was referring to a number of incidents in which authoritarian regimes cracked down on the opposition using European technology. In 2011, Bloomberg found out activists in Bahrain had been tortured while being interrogated about private messages the authorities had intercepted using equipment from the Finnish-German conglomerate Nokia Siemens Networks. And there are more cases like this.

Human rights? Profits come first

Time to curb the export of surveillance technology, the EU decided in 2014. But the regulations proved to be weak. Conventional arms regulations dictate that a country must refuse an export license if there is a “clear risk” that a weapon could be used for internal repression in the destination country.

But dual-use technologies aren’t subject to this rule. With them, the authorities can choose to prioritize other interests, like boosting economic growth or maintaining a good relationship with the country in question.

That means EU nations can decide for themselves whether to treat human rights as a decisive factor. “The regulation is mostly focused on security risks and is not geared to sufficiently address the risks of human rights violations,” says professor Quentin Michel, an expert on export regulations at the University of Liège.

The European Commission acknowledges the presence of a “regulatory gap” and has put forward a proposal to strengthen the law. The proposal would not require member states to deny licenses for exports that could endanger human rights. But it would strengthen human-rights language in the rule and include more categories of spying equipment than the three that are currently regulated.

Klaus Buchner, the European Parliament’s rapporteur on the proposal, says our investigation highlights the need for an update to the law. “The [denials of permission for 14] exports in your data set have in effect strengthened human rights and strengthened the EU as a trading partner,” he says. “The importance now is to harmonize this human rights-focused approach across Europe in order to overcome internal differences and patchy implementation.”

But it’s not clear whether the proposed bill will be passed. The Danish government, in a memorandum, said “there is a general skepticism among member states” towards the new rule. That’s because it differs from existing international agreements, such as the Wassenaar Arrangement, a voluntary but politically binding pact between 41 states regulating the export of munitions, tanks, missiles, guns, and digital weapons. The current EU rules are partly based on that agreement.

Member states also fear that the new emphasis on human rights would “create uncertainty about the interpretation and implementation and thus create large administrative burdens for both companies and authorities,” the memorandum said. The European Parliament will debate the proposal on February 28.

This piece is part of the investigative journalism project Security for Sale, reporting on Europe’s security industry in partnership with journalists from eleven European countries. Security for Sale is made possible by Journalismfund.eu

—Translated from Dutch by Laura Martz

More from Security for Sale:

The surveillance industry still sells to repressive regimes. Here’s what Europe can do about it

The European Union has tried in vain to stop the export of spying technology to despotic states. Why is the industry so hard to regulate? Here’s our analysis.

The surveillance industry still sells to repressive regimes. Here’s what Europe can do about it

The European Union has tried in vain to stop the export of spying technology to despotic states. Why is the industry so hard to regulate? Here’s our analysis.

How billions vanish into the black hole that is the security industry

The European Union spends billions on research into advanced technologies meant to make society safer. But our investigation with 22 journalists in 11 countries shows that the generous subsidies are mostly good for one thing: filling the coffers of the security industry.

How billions vanish into the black hole that is the security industry

The European Union spends billions on research into advanced technologies meant to make society safer. But our investigation with 22 journalists in 11 countries shows that the generous subsidies are mostly good for one thing: filling the coffers of the security industry.

Security for Sale. The price we pay to protect Europeans

The EU has deep pockets when it comes to security. But who reaps the benefits of generous subsidies? The public or the industry? For over a year now, we’ve worked with 22 journalists in 11 EU countries to investigate the European security industry. The result is Security for Sale, which brings you up to speed on this burgeoning sector.

Security for Sale. The price we pay to protect Europeans

The EU has deep pockets when it comes to security. But who reaps the benefits of generous subsidies? The public or the industry? For over a year now, we’ve worked with 22 journalists in 11 EU countries to investigate the European security industry. The result is Security for Sale, which brings you up to speed on this burgeoning sector.

More from The Correspondent:

This is how we can fight Donald Trump’s attack on democracy

The news provokes outrage every day, but it rarely inspires sustained resistance. Now that Donald Trump has launched a frontal assault on democracy, the press needs to fundamentally change tack. Journalists have to beat historians to the punch and write history – before it repeats itself.

This is how we can fight Donald Trump’s attack on democracy

The news provokes outrage every day, but it rarely inspires sustained resistance. Now that Donald Trump has launched a frontal assault on democracy, the press needs to fundamentally change tack. Journalists have to beat historians to the punch and write history – before it repeats itself.

A day in the life of a sniper fighting ISIS

In few places has the fighting against the Islamic State been as heavy and sustained as in the Syrian town of Kobani, near the Turkish border. The Kurdish population there slowly but surely took back their streets from the terror organization. Filmmaker Reber Dosky made the trek to Kobani and came back with a unique portrait of a sniper in a battered city.

A day in the life of a sniper fighting ISIS

In few places has the fighting against the Islamic State been as heavy and sustained as in the Syrian town of Kobani, near the Turkish border. The Kurdish population there slowly but surely took back their streets from the terror organization. Filmmaker Reber Dosky made the trek to Kobani and came back with a unique portrait of a sniper in a battered city.

Our kids may never get the chance to know America

This would be a dark chapter in US history even if Donald Trump had lost the election. But thanks to the incoming president, American democracy is in an accelerated state of decay. Is there anything we can do?

Our kids may never get the chance to know America

This would be a dark chapter in US history even if Donald Trump had lost the election. But thanks to the incoming president, American democracy is in an accelerated state of decay. Is there anything we can do?