Seated at the bar in an empty industrial building in the town of Hoogeveen, a group of Syrians drink coffee. Every now and then, one of the men goes outside to smoke. When they do, the haze from other smokers blows in through the front door, along with a gust of icy air.

Yet inside it’s warm and cozy – you can see it on their faces. The group laughs and eats pepernoten, those little spice cookies that show up wherever people get together in the Netherlands this time of year. They’re talking about how much they are going to miss this. They wouldn’t have thought so beforehand, they say, but they’re genuinely going to miss it.

It is the afternoon before the preview of At Home in Hoogeveen, a theater production put on by 22 Syrians – five women and 17 men – all of whom have been in the Netherlands for one to two years. Three more shows will follow tonight’s preview. And after that, it’s curtains for At Home in Hoogeveen, in any case in the current much-loved factory space.

When they started coming to this building each week, some two-and-a-half months ago, they didn’t know they would be putting on a play. Each of them had received a letter from city, which – due to their limited knowledge of the Dutch language – none of them had fully understood. They were under the impression that they were going to build a theater, or paint sets, maybe. In any case, some kind of manual labor.

Instead, the Syrians were asked to put on a play themselves, which makes At Home in Hoogeveen a unique project. Community theater as a means to integration – it’s something never before seen in the Netherlands. The question of whether the participants do indeed feel more at home here as a result of the play is not difficult to answer. The comraderie at the bar says it all.

In the evening, the atmosphere will be even warmer. Tickets are sold out and the entire former factory seems filled to bursting with the animated voices of a hundred Hoogeveen residents and the Syrians and their families.

“I can guarantee you that each and every one of us is really happy about this.” There are three more sold-out shows to come. And each of those evenings will end in one big Syria-meets-the-Netherlands encounter. It makes you wonder whether this kind of theater show isn’t more effective than a civic-integration textbook could ever hope to be.

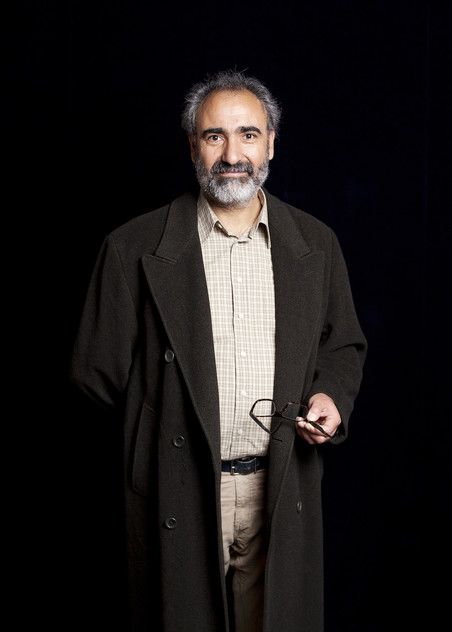

1. Anaas 2. Ramy Shams Aldeen

How to explain this success?

How can a project like this one, an idea that – on paper – sounds like nothing more than artsy-craftsy do-goodery, have such an impact? On the day of the only preview before opening night, I spent an afternoon and evening in the former factory, and came to understand what has taken place here.

How can a project like this one, an idea that – on paper – sounds like nothing more than artsy-craftsy do-goodery, have such an impact?

The day is dull and gray as I enter the equally drab building, one of those pre-fab numbers on an industrial lot on the outskirts of town. Inside, I nearly collide with Ramy Shams Aldeen, the singer in the group. He’s rollerblading through the corridors, over the indestructible industrial-grade carpet, a hold-over from the thrift shop that used to be housed here.

And just like that, the grayness dissipates. I find myself in an honest-to-goodness theater, with a large factory hall for the show, rows of bleachers to one side, and a bar tucked in the corner. There is a kitchen, as well as rooms that are being used as office-slash-bedrooms; these are equipped with inflatable mattresses.

An extra chance to get involved

The beds are where the Dutch people – the ones helping the Syrians put on their play – sleep. They are affiliated with Loods13, an organization that frequently stages theater events on location in the northern part of the country. “We prefer to put on our shows in an old, empty building. That way, we can use the space however we want and really make it our own,” artistic director Eva Wortmann explains.

Over the last four years, Wortmann has created a number of shows in cooperation with unemployed individuals in the Dutch province of Groningen. The purpose of these plays was two-fold: amuse an audience, while also boosting the actors’ self-confidence. When the province of Drenthe asked her to come do the same for the unemployed in Drenthe, she ended up in talks with the town of Hoogeveen – and they wanted her to involve refugees instead.

The town of Hoogeveen has some 55,000 inhabitants and has been tasked with housing 140 refugees with residence permits (called “status holders”) this year. Town officials soon noticed that many Syrians were eager to prove themselves, not only to potential employers, but to the other residents of Hoogeveen, too. “They want to show everyone: We’re good people, not terrorists,” says job coach Mariza Mircetic.

The project with Loods13 was intended to provide the Syrians with just such an opportunity. They were invited to take part on a purely voluntary basis. It was an extra way to get involved in Dutch society, on top of the integration course all status holders are required to complete. Officials selected dozens of status holders who had some kind of creative activity in their background in Syria, though “creative” was broadly interpreted. A guitarist and a painter received a letter at their homes – but so did a construction worker and an optician. And as I said, the specific content of that letter was lost on all of them.

1. Feras 2. Nancy Alhattab 3. Maheer Alokleh 4. Eva Wortmann

First, break the ice

And so on a bright September day, more than 20 Syrians stood in the sun, waiting outside an abandoned industrial building. Dani Heres Dominguez from Loods13 saw them standing there, making awkward small talk since they were strangers to one another as well. Heres Dominguez is a producer and director by trade, but Loods13 had hired him to break the ice, since the Syrians weren’t exactly enthusiastic about theater. “That’s one of my particular skills,” he says. “But it wasn’t an easy job.”

“I was a waiter back in Syria... and now you want me to act in a play?

He had to communicate mainly through gestures. “And with a sense of humor, because not every cultural difference has to be taken so seriously,” Heres Dominguez continues. It wasn’t until they were inside that the Syrians realized they would be expected to act in the play themselves.

And as it turned out, none were familiar with theater. Before the war, there were only comedy shows in Syria – but no one here had been to those. One man in particular was not amused: “I was a waiter back in Syria... and now you want me to act in a play?” One person quit on the spot, and a few others said they’d rather work in the kitchen.

The rest stayed, visibly reluctant – but after the first day, that had changed. Perhaps because in the beginning there was plenty of familiar work to do. They furnished the space with secondhand items and made arrangements for food. And in the meantime, they began to rehearse. They met two days a week, which was all the time they had to put together a play before the end of November.

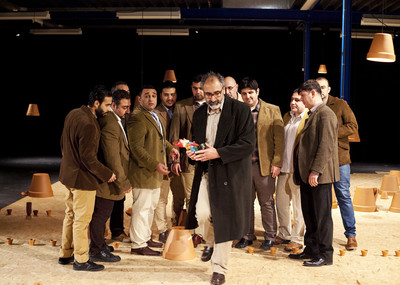

During the preview performance

And then: miscommunication and a lack of understanding

The initial idea was that everything – the story, the dialogue – would all come from the Syrians themselves. Their thoughts and feelings would be expressed in the play. That plan led to quite a bit of miscommunication, and not only because the Syrians’ Dutch wasn’t up to scratch.

Artistic director Wortmann and director Maarten Smit felt that the play should be about life in the Netherlands. That’s where they were living now, right? So they asked the Syrians: “What’s your biggest dream?”

“You can’t ask someone who just crawled onto the beach after a shipwreck what their biggest dream is. We’re all in survival mode

A heavy silence followed the question. Wortmann and Smit were perplexed, until guitarist Anas al Hallak said: “You can’t ask someone who just crawled onto the beach after a shipwreck what their biggest dream is. We’re all in survival mode.”

Al Hallak also remembers a game they were asked to play: tossing a ball to one another and then making a sound. “We thought that was really weird,” he says. But they kept at it. “New experiences are always good, right? They build character.”

1. Wassim Quiuon Al Soud 2. Nashat Hussain 3. Mohanad Sarraj 4. Dani

What the Syrians were trying to say

The turning point came when they all went to see Unknown Country by the Groningen theater company Het Houten Huis. It was a piece without any dialogue about a girl that had to find her way in a new country, where nothing made sense to her and everything was strange and new. It was an apt choice, something the Syrians understood immediately. “Would you all like to do something similar?” Wortmann and Smit asked. Yes, they would.

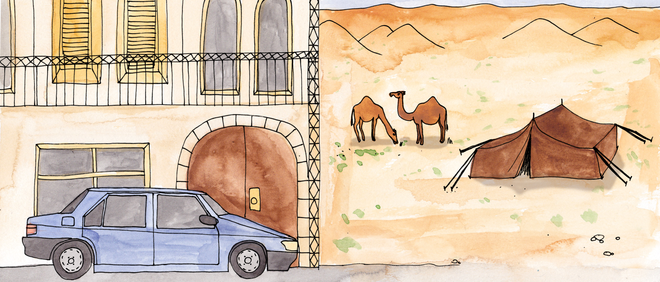

Except that the Syrians wanted to start with Syria. They wanted to show how good their lives used to be there, how husbands and wives would get up in the morning – a half-hour earlier than their children – just to spend time together listening to Fayrouz, a Lebanese singer beloved throughout the Arab world.

They want have one thing really get through to Dutch people – that they didn’t leave home voluntarily. They want to talk about the war, how they fled the country and about their arrival in the Netherlands after that, where nothing made sense to them and everything was strange and new. “We’re so isolated from everyone, how can we make contact with people?” they all asked. “We want to break down the wall, how can we do that?’

During the preview performance

They themselves had an inkling of what the metaphorical wall was made of: IS. After all, that was what they had seen on television and heard all around them – sentiments like “You know those Syrians are probably part of IS.” All 22 participants had the feeling that this was making normal communication with Dutch people impossible. They repeated it again and again, in their industrial building in Hoogeveen: “We are just like all of you.”

The Dutch people behind Loods13 started to realize that the play needed to be more than just a play. It needed to be a way to reach out, to make contact. They came up with the idea of sharing a meal with the audience after the show: shawarma sandwiches, bread and hummus, salad, tea, and baklava. They hung pieces of paper in the factory hall, as a place for the Syrians to introduce themselves, like the bulletin boards you sometimes see in supermarkets. They put their phone numbers at the bottom, on easy-to-tear-off strips.

Slowly but surely, the play took shape. It became a play without dialogue – which helped the actors lose their inhibitions. There was no need for them to speak in broken Dutch, except in a single scene. All they had to do was communicate images to the audience. Smit: “If you let the audience hear the sound of falling teacups at the beginning, and then at the end, the Syrians are putting the pieces of china back together, what more do you need to say?”

During the preview performance

The actors speak better Dutch than before

The first contact with the people of Hoogeveen occurred even before the preview. Two partial repetitions were held in front of an audience, which the actors had to arrange themselves – in the form of local residents. An added effect of two-and-a-half months of rehearsals: the actors’ Dutch-language skills were improving by leaps and bounds. It was consistently the language used by the Loods13 team.

The two groups spoke to one another a great deal, which affected the Dutch people as well. In the beginning, the team referred to “the refugees” when talking to one another. After that, it became “the status holders.” Then it was “the Syrians.” Then “the participants,” and then “the actors.”

And finally, those actors began to have names and faces. “They’ve become individuals, I can’t talk about them as some homogeneous group anymore,” artistic director Wortmann says.

1. Mutaah Daaboul 2. Maarten Smit

Theater has a therapeutic effect

And then finally, the day of the preview performance arrived – and Wortmann gets word that another theater, de Tamboer in Hoogeveen, wants to host the play on January 14 and 15. “Hopefully, this is the start of a nationwide tour!” she crows. The news is well-received by the Syrians at the pepernoten-strewn bar. Like they said, they’ve realized they’re going to miss the theater.

Following the very last rehearsal of the day, the Syrians have really loosened up. The women taking part in the show can’t help but notice, too. Randa el Kendi sees it, for instance; she says that their husbands have become much less serious than they were back in Syria. “It’s like they’re little boys again,” she giggles.

They’ve realized they’re going to miss the theater

She’s right. If you listen to their stories, these people have lost a child, or have a child in prison back in Syria. They know what it’s like to have an assault rifle pressed against your head, or to be tortured. Yet in this industrial space in Hoogeveen, they laugh and hurry about energetically, putting the finishing touches on the set or the tables bearing food.

It wasn’t exactly the intention, but At Home in Hoogeveen has had a therapeutic effect. One of the Syrians had refused to pretend to be sitting in a boat that would carry him and the rest across the Mediterranean. “It was only six months ago that I was sitting in a boat like that, and it still keeps my children up at night,” he explained. “I’d really rather not.” But four rehearsals later, he climbed into the boat after all.

1. Renate Dokter 2. Mohammad Kahil 3. Feras 4. Nsrin Al Rachid Abazid

They made contact with Hoogeveen’s residents

Ramy Shams Aldeen is practicing the songs he’s going to sing during the show, some of which originated in his hometown of Aleppo over a thousand years ago. After the trip by boat, he’ll perform a song about the country every one of the actors was forced to leave behind. “The first time I sang it, I wept,” he tells me.

During the preview performance of At Home in Hoogeveen.

And then the show begins; the singer himself is dry-eyed, although many a tear glistens among the people from Hoogeveen. A set of closed doors stands directly in front of the bleachers where the audience sits. The Syrians are on the far side, rattling the door handle – but the doors stay shut. Meanwhile, the voice of Geert Wilders blasts from the speakers, screaming that three-quarters of Muslims want to introduce sharia law.

The doors are rolled away and a story begins to unfold – about life in Syria, the flight from danger and prejudices in the Netherlands. "Shukran Hoogeveen,” one of the actors, Khalil Kader, calls out: Thank you, Hoogeveen. Behind him, the letters on a light box have been arranged to read, “ Full is full. Fuck you. Go back home.” He’s visibly frustrated by the sight.

It’s this kind of crude message that really hits hard. At the end of the show, the doors in front of the bleachers are back. This time, they open. The Syrians step through them, take the people of Hoogeveen by the hand and lead them to the food.

Over a plate of salad, audience member Saskia Oost remarks that maybe the Syrians don’t know how to make contact with the town’s long-time residents, but that the same is true for many of Hoogeveen’s Dutch people as well. Janneke Feijer, who is seated at the same table, says: “Here in Drenthe, we’re a little afraid of anything unfamiliar.” A Syrian refugee told her that his neighbors had brought him flowers. “Sometimes, it’s just that simple,” she says.

After dinner, people drift to the stage and begin to dance to the old songs performed by Ramy Shams Aldeen from Aleppo, Syrians and Dutch mingling on the crowded floor. In the factory hall, the first strips of paper with the Syrians’ phone numbers are being torn off.

1. Youssef Aldarbi 2. Kais Khaski 3. Amer Anbar 4. Khalil Kader

—This report is part of the New to the Netherlands initiative, which is made possible by support from the Dioraphte Foundation. Translated from Dutch by Liz Gorin and Erica Moore

More from New to the Netherlands:

Seven things the Dutch need to understand about how refugees here feel

Some 300 newcomers to the Netherlands have answered thirty questions asked by members of De Correspondent. It was the largest group interview ever conducted with refugees in this country. Today: the answers to a single question.

Seven things the Dutch need to understand about how refugees here feel

Some 300 newcomers to the Netherlands have answered thirty questions asked by members of De Correspondent. It was the largest group interview ever conducted with refugees in this country. Today: the answers to a single question.

Hundreds of Correspondent members asked refugees about life in a new country. Here’s how this unique initiative got started

We’ve all seen news reports on refugees fleeing war, famine, or persecution in their home country, desperate for a better future elsewhere. But what happens to refugees after they arrive in a new land? To find out, De Correspondent mobilized hundreds of its members. And asked.

Hundreds of Correspondent members asked refugees about life in a new country. Here’s how this unique initiative got started

We’ve all seen news reports on refugees fleeing war, famine, or persecution in their home country, desperate for a better future elsewhere. But what happens to refugees after they arrive in a new land? To find out, De Correspondent mobilized hundreds of its members. And asked.

The hairdresser’s amazing comeback (or why everybody needs a Fatima)

It took Maher Mansour four years to build a business in this country as successful as the one he’d owned back in Syria, before he lost everything. His dream wouldn’t have come true without Fatima El Kaddouri. If only every refugee had a Fatima.

The hairdresser’s amazing comeback (or why everybody needs a Fatima)

It took Maher Mansour four years to build a business in this country as successful as the one he’d owned back in Syria, before he lost everything. His dream wouldn’t have come true without Fatima El Kaddouri. If only every refugee had a Fatima.