The Amazon is a vital organ in the global biosphere. Often called the “lungs of planet Earth” by climate researchers, it’s also “the heart” – in an ecological sense, but also as an emotional and mythic anchor for humanity. Forests create rain, and none more than this one. The Amazon is the biotic pump of the Earth, drawing more than 20% of the world’s fresh water through its hydrological cycle.

Without the Amazon, our planet’s ecosystem would collapse.

In the aftermath of the fires which ravaged the Amazon in 2019, awareness of the varied threats to this precious natural resource has soared. The fires which occur every year are increasing in scope and size, largely due to mining and extractive industries, large-scale soy farming and cattle ranching.

New research shows these threats are more dire than was previously understood. What scientists call the “Amazon tipping point” is approaching faster than predicted.

Who is responsible for driving this destruction?

The culprits at government level include all nine nation states of the Amazonas region (Brazil, Ecuador, Venezuela, Suriname, Peru, Colombia, Bolivia, Guyana, and French Guiana). Their governments adhere to the neoliberal, global creed which demands GDP growth at any cost.

Indigenous peoples know the Amazon with an intimacy beyond words: their presence protects the environment against the onslaught of corporate and state interests

No less complicit are the globalised demands of industrial capitalism and its consumer culture, serviced by large corporations. Amazon Watch, an NGO, recently published a report on the companies driving deforestation in the region. There’s no room for doubt that the insatiable addiction of our global economy to extraction is, quite literally, razing the Amazon rainforest.

We often hear about the impact of industrial capitalism on the natural world. It’s less common to hear about the concomitant damage to living memory – the loss of cultures, dances, medicines and ancient wisdom – in its wake. Intertwined with this destruction is the methodical extinction of an extraordinary number of the living beings that populate our ecology.

As writers and researchers, our work explores alternative narratives as a way to balance or resist mainstream discourse. What we found most striking in the Amazon is a lack of interest and the absence of dialogue with Indigenous peoples whose ancestors have stewarded this land for centuries, if not millennia.

For those of us socialised in the west, their example is too important to ignore. These are people who know the Amazon rainforest with an intimacy beyond words. Not only have they survived but their presence has protected and enhanced their natural environment, despite the onslaught from corporate and state interests.

We can, and should, learn in all humility from the example of these cultures. Indeed, we believe that their knowledge of how to live in symbiosis with the natural world may be the key to ensuring the continuity of our species on this planet.

The ‘Cure of the Earth’

Indigenous peoples, who make up only 4% of the global population, are directly responsible for or oversee more than 80% of the world’s biodiversity. Where Indigenous people steward land, we find evidence of richer biodiversity and healthier ecosystems. These benefits are often sustained in Indigenous communities by deep appreciation and respect for the needs of other species, which then further contributes to what scientists call positive feedback loops.

This example is under attack in Brazil. President Jair Bolsonaro, the far-right leader of South America’s largest country who took office in January 2019, has declared war on the Amazon. His agenda is endorsed by some industrialised European states. For example, recent reports have highlighted the alleged complicity of the UK government in Bolsanaro’s "pro-development" policy to raze the Amazon for agribusiness and mining for minerals.

We are the first inhabitants of the country. We do not only defend the environment: we are Nature itself – Piaraçu Manifesto

The rate of murders of Indigenous activists in these communities continues to rise. Sonia Guajajara, an activist and organiser with Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), reminded us that Indigenous peoples are often known as the Cura da Terra, the Cure of the Earth. As the name implies, a combination of their ancestral knowledge and practical experience equips them to preserve and regenerate the rainforest through the restoration of Indigenous land management practices.

Indigenous methods of conservation are losing ground, literally and metaphorically. Recent data suggests that by April 2020 the deforested area in the Brazilian Amazon increased in size by 171% compared to a year earlier. This brutal statistic is emblematic of the wider trend of national governments prioritising the pursuit of short-term economic growth above the shared interest of all humanity in preserving the Earth’s natural ecosystems. As we wrote here, citizens of every country need to understand how we’re consuming the finite resources of our living planet.

Before it’s too late.

The convergence of factors which will drive this region to the Amazon tipping point are causing the rainforest to die off, releasing massive amounts of carbon into the atmosphere. Carlos Nobre, a renowned climate researcher at the University of São Paulo, forecasts that the central Amazon region will be transformed into a desert-like savannah. At the current rate of destruction, this could happen within 10–15 years.

The Piaraçu Manifesto

In January 2020, representatives from more than 45 Indigenous communities gathered in the small village of Piaraçu in the Xingu Basin of the Amazon. Their meeting, attended by 600 participants, was convened by Chief Raoni, legendary chief of the Kayapo people who has been nominated for the 2020 Nobel Peace prize. We had the honour of joining this meeting as delegates from an international group of media and civil society organisations.

Over the course of four days, participants came together to share their sacred songs, dances and ancient stories. In the face of imminent catastrophe, their contributions to this historic event combined in a vibrant celebration of living memory, weaving together the threads of rainforest cultures into a sophisticated tapestry. By the close of the meeting, Indigenous leaders had drafted the Piaraçu Manifesto, a collective statement of resistance.

The four-page document makes clear that the Brazilian government’s actions represent genocide, ethnocide and ecocide. It articulates their demands as custodians of the rainforest, to remind the Brazilian government of the critical role for Indigenous peoples in the preservation of the rainforest: “We are the first inhabitants of our country. We do not only defend the environment: we are Nature itself.”

The Eagle is a figure for the rational, the industrial and the masculine. The Condor represents intuition, connection to the Earth, the feminine

As the Manifesto argues, Indigenous communities across the Amazon are taking action to protect the biome from extractive industries. Their presence is essential to the preservation of indigenous species and the promotion of biodiversity. The deep attachment and respect of Indigenous peoples, often manifested in their offerings to the land, helps to maintain a culture of balance and reciprocity between humans and the Amazon’s more-than-human world.

This example is a lesson for the world, argues Atossa Soltani, founder of Amazon Watch and a recently created Amazon Emergency Fund. “What happens in the Amazon affects the entire planet. We cannot allow rich, industrialised nations to continue to push their agenda for economic growth at all costs when the lives of so many humans, and so many other species, are on the line. We know Indigenous stewardship of the land is the only sane response to managing the Amazon before it’s too late,” she says.

Indigenous prophecies

As we pursued our research into alternative narratives, we were struck by the prescience of Indigenous prophecies which presage this moment in the long history of the Amazon. From interviews with Indigenous leaders, we heard about the prophecy of the Eagle and the Condor, a potent story that permeates the cultures of many First Nations in North and South America.

The Eagle and the Condor would fly together in the same sky – a new level of consciousness for humanity

The prophecy speaks of human society dividing along two paths, following the Eagle (from the North) and the Condor (from the South). The Eagle is a figure for the path of the mind: for rationalism, the industrial, the masculine. The path of the Condor is that of the heart, intuition, connection to the Earth, the feminine.

The Eagle and Condor prophecy tells that the colonisation of Latin America from the 1490s began a period of about 500 years during which the Eagle people would become so powerful that they almost wiped out the Condor people. Then comes the next 500-year period, when the potential would arise for the Eagle and the Condor to come together, to fly in the same sky, creating a new level of consciousness for humanity.

The resonance of this prophecy in our current moment needs no elaboration. We have reached a juncture, the moment where our civilisation will decide if these two attitudes or ways of living can learn from each other.

If we choose to continue on our current path, the western mode of consumption will allow our species only a slight chance of survival. This is a moment when the industrialised nations must begin to discover what can be learned from cultures which exist without destroying the planet. How do we humble ourselves to those who know what it means to be a companion species on the living Earth?

Given the issues now confronting us – the Amazon Tipping Point, Covid-19, ecological breakdown, a resurgence in the movement for racial justice, the neo-colonialism of global finance and impending economic recession – there couldn’t be a better time to seek a cure. The logic of our life-destroying culture needs an antidote logic. Our ability to respond, indeed our responsibility to do so, is intertwined with the meaning and potential of prophecy.

Felipe Viveros and Alnoor Ladha are researchers, journalists and activists. They are board members of Culture Hack Labs, a not-for-profit dedicated to shifting the dominant cultural narratives that create inequality, racism, poverty, patriarchy and ecological breakdown.

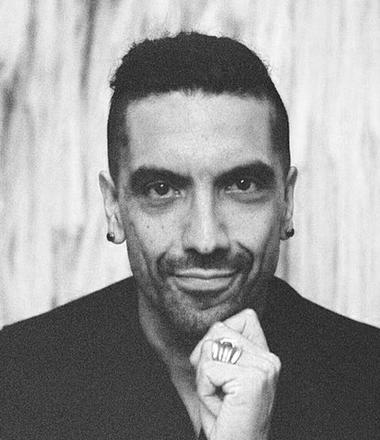

About the images

In these diptychs, photographer Pablo Albarenga depicts sacred ground as a backdrop to his portraits. The series explores the relationship of Indigenous people to their environment. Each portrait is paired with an aerial view of a soya bean field, a new road or a bauxite mine. The subjects are human shields for land ravaged by agribusiness, mining and pollution. Their stance is more than a pose; Amazonian communities continue to defend their territories from external threats, despite the deaths of more than 200 activists in 2017.

About the images

In these diptychs, photographer Pablo Albarenga depicts sacred ground as a backdrop to his portraits. The series explores the relationship of Indigenous people to their environment. Each portrait is paired with an aerial view of a soya bean field, a new road or a bauxite mine. The subjects are human shields for land ravaged by agribusiness, mining and pollution. Their stance is more than a pose; Amazonian communities continue to defend their territories from external threats, despite the deaths of more than 200 activists in 2017.

Dig deeper

Sapiens: groundbreakingly original in the history it tells, predictably disappointing in the history it leaves out

I read Yuval Noah Harari’s self-described history of humanity to see if it had a place for someone like me. But although Harari’s bestseller promises a satellite view of human history, it has some very traditional blindspots.

Sapiens: groundbreakingly original in the history it tells, predictably disappointing in the history it leaves out

I read Yuval Noah Harari’s self-described history of humanity to see if it had a place for someone like me. But although Harari’s bestseller promises a satellite view of human history, it has some very traditional blindspots.

Meet Julian Brave NoiseCat – the 26-year-old shaping US climate policy

This man helped to draft the Green New Deal – the most radically progressive environmental and economic policy the US has seen in decades – about identity, climate justice, and hope for the future.

Meet Julian Brave NoiseCat – the 26-year-old shaping US climate policy

This man helped to draft the Green New Deal – the most radically progressive environmental and economic policy the US has seen in decades – about identity, climate justice, and hope for the future.