After the coronavirus, flying may never be the same. The introduction of temperature checks at airports and social distancing rules on aircraft mean taking a holiday or travelling for work will be different. Some airlines will stop offering food. Ryanair, persistently the world’s most unsentimental airline operator, now forbids passengers to queue for the toilet.

Fewer people will be allowed to travel in the same cabin space, making the whole business a lot less profitable than before. But that hasn’t stopped governments the world over from doing their best to revive the aviation industry to its former glory.

By early May, as the bailout season began, states had devoted $85 billion to propping up airlines. Despite this, in early July demand for flying in the US, the world’s largest market, was still down by 75%. More bailout packages are on the way.

Across the world, the dominant policy in every country appears to be to put as many airplanes back in the air as soon as possible. Passengers have missed travel during the lockdown, according to Ed Bastian, chief executive of Delta Air Lines. Doing things over Zoom was fine for a while, “but business is done face-to-face. We’ll get back”, he told the Financial Times.

If he’s right, we’re fucked.

I’m sorry to be so blunt. We really do have to acknowledge the hard truth. If we return to flying as we did before Covid-19, we’ll never bring global warming under control.

The urgent need to fly less may feel painful. It spells the end for a certain way of living. Since the ending of the second world war, flying has been associated with shifting boundaries, meeting people, new experiences and the discovery of new cultures. "Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness,” wrote Mark Twain. He was right.

In flight over planet earth, holidaymakers, business people, academics would all sit together, paging through the same magazines, listening to announcements from the cockpit. It was sweet.

But looking at the facts about flying and climate, we can arrive at only one conclusion. To keep the planet liveable, those of us who fly need to do it much less, or stop altogether.

Why flying is so bad for the climate

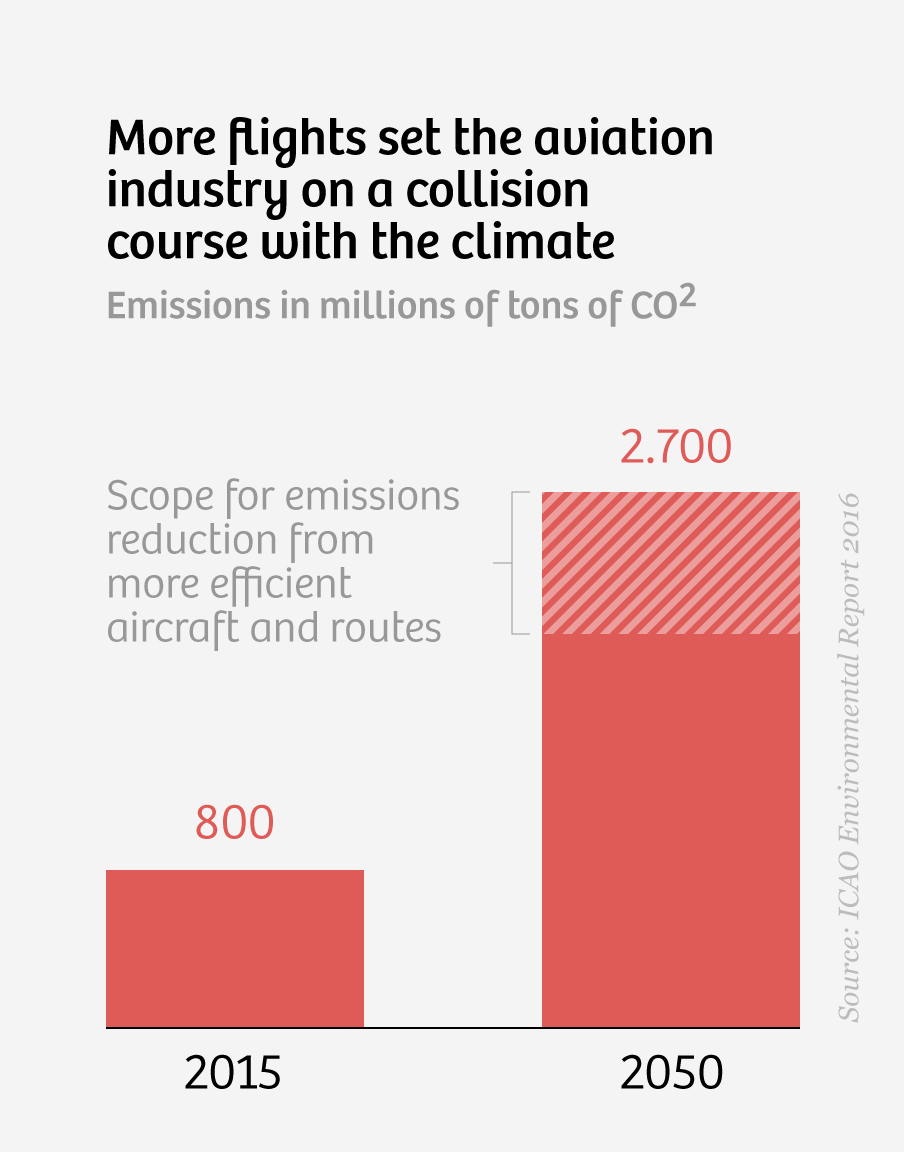

Flying is a small but growing source of emissions. At just over two percent of global CO₂ emissions, it currently represents only a limited share of the total. But prior to coronavirus, this expanding industry was forecast to account for a fifth of all emissions by 2050.

It may take the industry up to five years to recover from recent lockdowns, according to Airbus chief executive Guillaume Faury. But, noted The Guardian, even that "short-term outlook was coupled with longer-term optimism that the aviation industry will rebound and grow”. As it always has done in the wake of past crises.

Before Covid-19, Airbus expected the wider aviation industry to build 39,000 new aircraft by 2038, a doubling of the global fleet. And because all those new planes will be flying on jet fuel for at least 20 to 30 years, CO₂ emissions will go through the roof.

To date more than 80% of the world’s population has never flown, but rising incomes coincide with a clear trend in passenger flight: many people start to travel by air as soon as their budget allows. By 2022, China is forecast to overtake the US as the world’s largest market for air travel.

Growth on this scale is incompatible with meeting climate targets. It literally flies in the face of a climate-friendly lifestyle.

A Boeing 747 carrying 410 passengers burns through the equivalent of four bathtubs of jet fuel per person

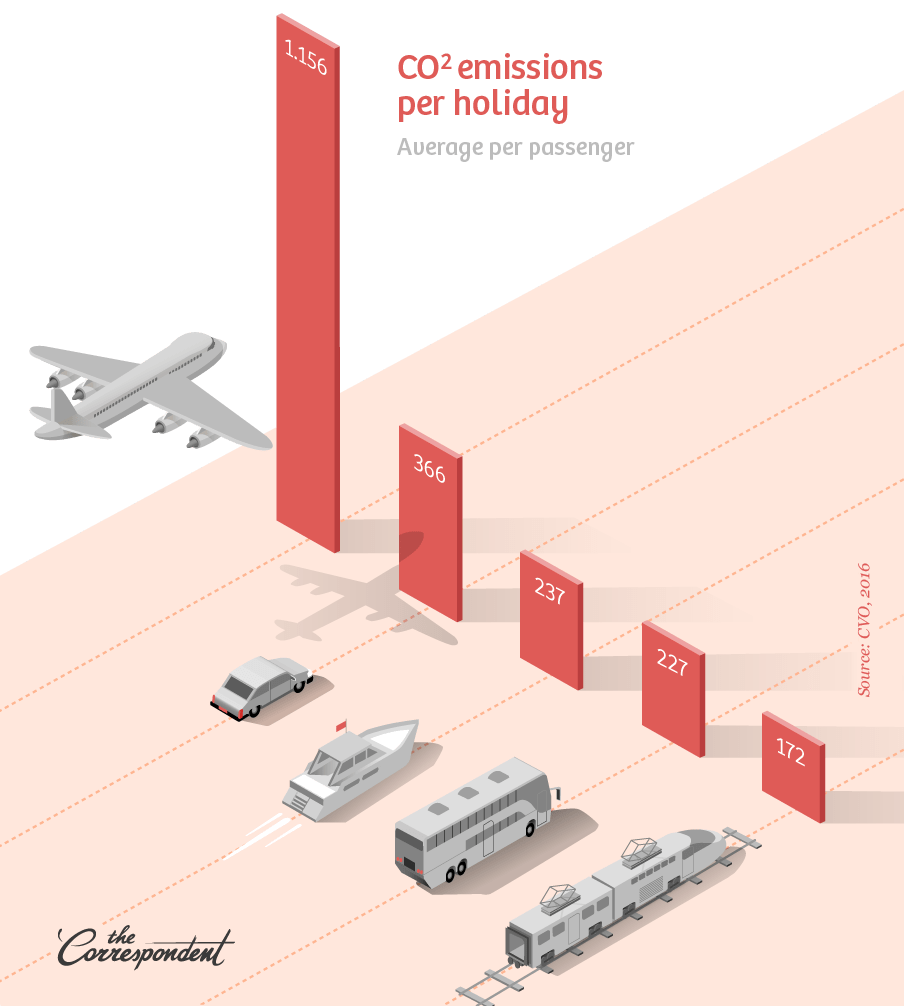

Perhaps you have already decided to give up meat for the sake of the climate: did you know that one return flight from London to New York is as bad for the climate as consuming almost 1,000 Big Macs? Have you swapped old lightbulbs at home for environmentally friendly LEDs? The CO₂ you will save over five years is cancelled out by one medium-haul flight, from, say, Berlin to Lisbon.

I’m not saying these things to suggest that vegetarianism and energy saving are pointless. On the contrary, these are effective steps to lower your carbon footprint. But here’s that uncomfortable truth again: if we continue to fly, we will undo the progress made in many other areas.

Why is flying so bad? Because it takes a lot of energy to lift a metal bucket full of people and suitcases into the air. Go figure: a Boeing 747 burns more than 190 tons of kerosene for an average long-haul flight. With 410 people on board, that’s four bathtubs per passenger. Burning that fuel emits 530 tons of CO₂. That’s nearly 2.5 times the weight of the plane, all deposited in the atmosphere.

And those trails produced by aeroplanes? That’s frozen condensation. For each molecule of water, another molecule of CO₂ is left behind. And that we can’t see. Here’s another uncomfortable truth. Flying not only contributes to climate change through CO2. Emissions of nitrogen oxides, water vapour and aerosols also change the composition of the atmosphere.

Vapour trails have a direct effect on warming, and also cause clouds to form. The net result of all these effects is more warming, making the total climate impact of flying two to four times that of CO2 alone.

And then there are the ultrafine particles emitted by aeroplanes, the noise pollution and biodiversity damage. These impose further costs borne by society (when people become ill, for example), but which, like CO₂ emissions, are not included in the price of a ticket.

The illusion of low emissions flying

We’re in the habit of hearing that technology can save us – or at least, our lifestyles. Electric-powered flight is often claimed to be the answer to all these challenges. Some small aircraft already are capable of flying on electric power, but passenger flights across the ocean? That’ll take decades at least, simply because batteries aren’t yet good enough.

Alternative fuels such as hydrogen or synthetic kerosene can power aircraft, but at a price. Not only are they expensive, these fuels constitute an improvement only if there’s a surplus of green electricity to produce them – which is not yet the case.

The aviation sector overall intends to use more biofuels. This means scarce agricultural land will be used to grow crops that – after conversion – will be burned in aircraft. Because there isn’t enough land currently available to grow these crops, additional demand for biofuels will add to the destruction of the world’s tropical forests. If the aviation industry has its way, we will be flying at the indirect expense of the last untouched woodlands on earth.

What about offsetting emissions by planting new trees? That will never be enough. Even if you choose a good project, the benefits will only come about after a period of years. Compensation schemes do not reverse the negative impact in the short term. Nor will they reduce emissions other than CO₂. The best outcome of offsetting is that, decades later, the level of CO₂ will be the same as it was before you got on the plane.

If you’re hoping for a technological breakthrough: sorry, I have to disappoint you. The aviation sector likes to talk about improving the efficiency of aircraft, but passenger volumes and flights are increasing so fast that every drop of jet fuel saved through efficiency is still burned elsewhere by another flight.

Rules are made to be flouted

In a "business as usual" scenario, aircraft emissions will triple by 2050 compared to 2018 levels. Recent reports suggest that just before the coronavirus hit, the actual trajectory was even steeper.

So the burning question remains: will we return to flying as we did before the Covid-19 crisis?

So far, it looks very likely that we will. Governments and regulators continue to treat aviation as an exception. While every economic sector is asked to lower its emissions, aviation gets free pass after free pass to pollute.

States have attached few, if any, climate-related performance conditions to the terms of bailout packages. The sector is conspicuous by its absence – and largely unmentioned – in most of the national policy plans drawn up by countries under the Paris climate agreement.

As if to confirm that aviation is privileged over other sectors, more often than not jet fuel is exempt from taxation

In 2016, under the auspices of the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), a UN agency, it was determined that airline companies should compensate part of their CO2 emissions. The combined emissions of all aircraft in 2019-2020 would be the point of reference: all CO2 emissions beyond that level would have to be compensated from 2025. At least, that was the plan before coronavirus. Recently, the reference year was moved back to 2019, a busier year for air travel, to allow higher uncompensated emissions in the short term – another free pass.

These policies are designed so that other sectors – which must adhere to Paris goals – are required to work harder to limit emissions, while the aviation sector continues to pollute.

The ICAO plan is billed as "carbon neutral growth". But there’s nothing "neutral" about it, since in years to come all CO2 emissions up to the level set by the reference year will not incur charges. Only emissions above that threshold are to be compensated. You could compare this dubious arrangement to a landlord renting out 10 apartments that are known fire hazards, while announcing a plan to fireproof an 11th apartment by 2023.

Moreover, compensation – via the main international market for carbon offsets – is barely working. To date, 85% of the projects included in these schemes only produced additional emissions reductions on paper.

In fairness, some serious attempts are being made to put a price tag on CO2 emissions from aviation.

Within the EU, for instance, flights fall under the "emissions trading system" designed to make carbon emissions expensive and clean alternatives more attractive. But airlines are still granted special treatment. They are given about half of their permits ("allowances") for free. The balance of the pollution permits are still so inexpensive that they hardly affect emissions from aviation in the EU – until the Covid-19 outbreak, those continued to rise.

Beyond Europe, the only country to put a price tag on CO2-emissions from domestic aviation is South Korea. China has signalled an intention to price domestic aviation emissions at some point, and a pilot scheme is underway in Shanghai. The time frame for any commitment or wider implementation is not known.

That’s it: the whole, brief story of environmental regulation of air travel! No other schemes exist to price carbon emissions from aircraft. As if to confirm that aviation is privileged over other sectors, more often than not jet fuel is exempted from taxation.

No other sector enjoys such generous and routine exemptions. In aviation, until very recently, they were considered normal by policymakers who wrote them into the small text of hundreds of bilateral global "air transport agreements". These documents are the basis of what amounts to a kind of trade agreement about flying, its details so obscure that this is probably the first time you’ve heard about them.

A flight path for activists

Luckily, there’s some progress. In the last couple of years, some governments have started to renegotiate air transport agreements in an attempt to create the legal space necessary to introduce taxes on jet fuel. In Europe, no legal roadblocks remain. In France and the UK specifically, regulators are considering serious climate goals for the aviation sector.

In many countries, activists are taking the lead by campaigning against the expansion of airports. Some have taken their battle to court. A recent lawsuit against the plans to construct a third runway at Heathrow Airport in London made headlines when the judge ruled that the expansion would be in violation of the Paris climate agreement. The legal precedent contrasts with a similar case against Vienna-Schwechat Airport Expansion which failed in Austria just three years ago – a testament to the coming of age of climate litigation.

Court cases alone will not be enough. Legal processes are slow, and jurisdictions vary. We urgently need better alternatives to flying. More high-speed train connections could make a sizeable chunk of current flights redundant, a cause taken up by many climate organisations and NGOs.

The 12% of Americans who fly more than six round trips a year are responsible for two-thirds of all aviation emissions from the US

Protests are becoming more frequent, as more concerned citizens around the world join the call for tougher climate measures in aviation. The longer these protests continue, the more likely they will have an effect: politicians may take a long time to listen when people raise their voices, but eventually, they do listen when enough citizens make themselves heard.

Government action – in the form of much higher taxes on aviation, and real disincentives for flying – is absolutely necessary. At this critical juncture, with the industry on a government lifeline, the time for that action is now, when politicians have unusual leverage over airline CEOs and industry lobbyists.

A recent report for the European Commission found that “taxing aviation kerosene sold in Europe would cut aviation emissions by 11% and have no net impact on jobs or the economy as a whole”. Another study calculated: “If the biggest emitting countries in Europe agreed to tax kerosene, it could bring up to €3.7 billion per year.”

That’s no-brainer policy right there.

But.

We don’t have to wait around for governments and regulators to get their act together. Flying less is a personal choice, and one of the most effective things you can do as an individual to limit climate change.

It’s perfectly doable, believe me. Although it’s been more than 10 years since I gave up meat because of my worries about climate change, until recently I still liked to fly. Then in 2015, I made a return trip to New York. When I did the sums and realised that one trip was the climate equivalent of eating 1,000 Big Macs, something clicked. That was about two and a half years ago: I haven’t set foot in a plane since.

And guess what? It’s been fine – better, even. I’ve been on more interesting holidays (Europe by train in my case) and I haven’t felt that I’m treated like cattle by queuing in the uncomfortable holding pens that we call airports.

Of course, some people really need to fly to see family or keep their jobs. If you’re one of those people, you could compensate for your emissions by supporting certified reforestation projects. Various guides are available online. Providers including goldstandard.org and standfortrees.org offer reliable schemes.

Better still: compensate tenfold. The more trees you pay for, the higher the chance that the patch of wood you’re planting or protecting will survive long enough to yield some net compensation for your actual emissions.

But honestly, compensation will never be enough. Paying other people to clean up your emissions is bad strategy. It’s not sustainable, especially if you already fly frequently, flying less is what you need to do.

In my own country, The Netherlands, highly educated people and high-income earners fly four times as often as people with a low level of education and those with low incomes. How equitable is that? In the UK, the top “10% most frequent flyers took more than half of all international flights in 2018”. Just one percent of English residents are responsible for almost a fifth of all flights abroad.

In the US, a recent analysis found that the “12% of Americans who make more than six round trips by air a year, are responsible for two-thirds of aviation emissions”. Skewed, right? It’s only fair that frequent flyers should take a step back or stop completely. If you belong to one of these groups, why not consider booking a train, choosing a different holiday destination or conducting your next meeting by video call? As the recent lockdowns proved, virtual working is perfectly doable.

If the people who still fly act of their own will to restrict their freedom even a bit, their action would increase the freedom of others. Because ultimately, it’s the poorest people who are most exposed to the worst effects of global warming. Did all our flying really make us more cosmopolitan? Then it’s time to act accordingly.

You can read more about our future on a hot earth in my book How Are We Going To Explain This? available now from Profile Books (UK) and from Scribner (US) in November.

Translated from the Dutch by John Edwards, Laura Vroomen and Anna Asbury. You can also read the Dutch version of this article.

About the images

The images in this piece are from the project Paper Planes (2014) by visual artist Sjoerd Knibbeler. He made folded paper models from designs which never made it past the drawing board, then managed to get the planes airborne. Knibbeler’s series references our drive for innovation and the romance in ideas about flight. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

The images in this piece are from the project Paper Planes (2014) by visual artist Sjoerd Knibbeler. He made folded paper models from designs which never made it past the drawing board, then managed to get the planes airborne. Knibbeler’s series references our drive for innovation and the romance in ideas about flight. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Dig deeper

Renewables are cheap and effective. Now, let’s make them just and humane too

The technological chapter of climate transformation can be whatever we choose to make it. If we allow it to be a bulldozing, profit-driven enterprise, the energy transition will fall apart – ratcheting impacts of climate change.

Renewables are cheap and effective. Now, let’s make them just and humane too

The technological chapter of climate transformation can be whatever we choose to make it. If we allow it to be a bulldozing, profit-driven enterprise, the energy transition will fall apart – ratcheting impacts of climate change.

If we want the future earth we deserve, we need to do things that scare us

We’re at a transformative moment in history – from an old world based on extraction and exploitation to a new world that we must create as we go. Embracing discomfort is at the core of climate action. And it’s something we’re all capable of.

If we want the future earth we deserve, we need to do things that scare us

We’re at a transformative moment in history – from an old world based on extraction and exploitation to a new world that we must create as we go. Embracing discomfort is at the core of climate action. And it’s something we’re all capable of.