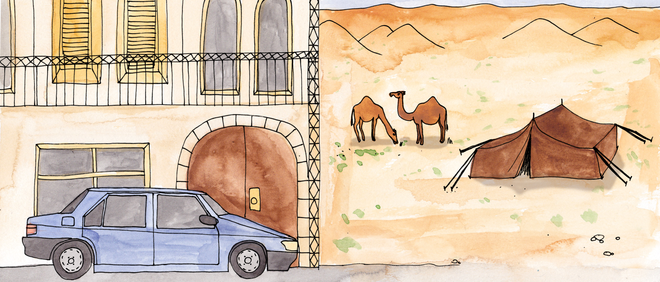

Many refugees who have been living in the Netherlands for less than eighteen months retain a strong focus on their country of origin. They are deeply worried about the family members left behind.

They keep a close eye on events in their homeland: so close that it sometimes borders on obsession. Events there are largely responsible for how they feel on a given day. So far, there’s no escaping their old life.

That applies to the over 200 newcomers taking part in the New to the Netherlands initiative. For the second time, they filled out a questionnaire together with a member of De Correspondent. This time, our questions focused on ties with their homeland and the family reunification procedure. The results are not representative for all newcomers, but serve as a starting point for journalistic research.

1. Events in their homeland largely determine their mood

How often do you check your phone, look online, or turn on the TV to find out what is going on in your homeland? That was one of the questions. Two-thirds answered: every day. For three-fourths, the things they hear or see about their homeland influence their mood “greatly” or “to an extreme extent”.

For three-fourths, the things they hear or see about their homeland influence their mood “greatly” or “to an extreme extent”

By way of comparison: two out of five respondents keep track of current events in the Netherlands on a daily basis. For half of these, what happens here influences their mood “greatly” or “to an extreme extent”.

In other words: the majority of participants are more deeply impacted by developments in their country of origin than by what goes on in the Netherlands.

One in three thinks that the Dutch have a “good” or “reasonably good” awareness of what’s happening in their homeland; according to one in four, this awareness is “bad” to “reasonably bad”.

2. Refugees are deeply worried about those left behind

Many of the newcomers interviewed are highly concerned about the fates of family members back home. Half of respondents are in touch with relatives in a foreign country on a daily basis; in most cases, they use WhatsApp and Facebook. Nearly all of them place great importance on that contact; nine out of ten say it’s “very important”.

Contact with friends outside of the Netherlands is also important, but less so than the contact with family. One in seven of the refugees interviewed by our members has contact with friends every day. For one quarter of the participating newcomers, that interaction is “very important”.

For every five respondents, four of them worry “greatly” or “to an extreme extent” about their family. The most intensely emotional reactions were given in response to the open question of what it is, specifically, that they worry about.

When you call family in Syria and they fail to pick up the phone, that’s cause for real concern.

Nearly everyone said they were afraid that relatives wouldn’t survive the situation in their homeland – for the majority, that’s the war in Syria. Some of them have already lost family members, like the man who said through tears: “My father was killed in Aleppo this weekend, and now I’m extremely worried about my mother.” A handful of the refugees don’t know if their families are alive or dead. When you call family in Syria and they fail to pick up the phone, that’s cause for real concern.

Respondents also worry about the lack of money, food, and medical care in Syria. The country has yet another problem, one that appeared on five of the questionnaires we got back: kidnappings. Men are being snatched off the street by the government, IS, warlords, or gangsters and given a choice – join the fighting or go to prison. Some of the newcomers are afraid this might happen to their brothers, uncles, nephews or cousins as well.

For instance, one person said: “I’m scared that our fathers and brothers will be arrested by Bashar al-Assad’s regime, or by a fake militia – that they’ll be taken, car and all, and never come back. That kind of thing happens all the time. People leave home and are never heard from again.”

And then once family members have fled Syria, other problems arise. Do they have enough money to survive? One newcomer wrote: “When it comes to friends and family outside of Syria and the Netherlands, I worry about them living in isolation and whether or not they can take care of themselves.”

While those interviewed were most concerned about family members, the safety of their friends was a source of concern as well. “Every time the government issues orders to the military, like to search people’s homes or start a war with Ethiopia, I’m afraid it will have consequences for my family and friends,” one newcomer from Eritrea wrote about their homeland.

3. Two out of five refugees have applied for family reunification

Family reunification was a second theme of the questionnaire. Two out of five respondents said they had applied for family reunification. Reunification is only an option for a spouse or children. Minors can apply on behalf of their parents. A quarter of the newcomers said they applied on behalf of a single family member, half of them applied for two or three other people, and the remaining quarter of respondents applied for reunification with four or more family members.

For nearly half of the participating newcomers, that application has already resulted in successful reunification with family members in the Netherlands. One in ten newcomers, on the other hand, has had at least one application rejected. One in four has an application still pending. And finally, one in seven has been told their application is approved, but are currently waiting for reunification to take place.

Two out of five participants had applied for family reunification

Only three newcomers reported that their application was approved but that it was impossible to carry out. Those stories are the most harrowing. We’ll be coming to back to them in a subsequent report.

When it comes to how family reunification in the Netherlands is being managed, newcomers’ opinions seem to vary widely. Half of them reported being “satisfied” to “very satisfied”. One in three, however, is “dissatisfied” to “very dissatisfied”.

Half of the participating newcomers currently have family in the Netherlands. Nearly all of them – more than nine out of ten – have friends in this country. Still, two out of five report feeling lonely either every day or a few times a week. One in three worries “greatly” or “to an extreme extent” about their own well-being. Which means that the majority is more concerned about family and friends in other countries than about how they themselves are getting along in the Netherlands.

All told, it’s safe to conclude that many of the newcomers our members spoke with are preoccupied with concern for family back in their country of origin, and with worries about being reunited with them.

4. Other responses and stories

We asked two additional open-ended questions: What do you miss most about your homeland? and What do you like about the Netherlands? We also asked for a photo of something in the newcomer’s home that reminds them of their homeland. We published a selection of the responses and photos in the Dutch-language edition last week.

This time around, we received 223 completed questionnaires. That’s about 50 fewer than last time. Often, the reasons why the Correspondent member or newcomer were unable to take part were basic or trivial. “Too bad – haven’t been feeling well!” was one submission. Another member reported: “We weren’t able to complete the questionnaire this time. Thanaa said that after we filled out the first one, she started worrying about Syria.”

Some newcomers were simply too busy at the moment, because they were looking for an internship or painting their house in anticipation of being reunited with family members. And a few had more important things on their minds after getting “some really bad news about family back in Syria,” as one Correspondent member wrote. Or the newcomer was working on a presentation “about De Correspondent” for class.

In one case, the contact between a Correspondent member and a newcomer ended in a head-on confrontation: “I quit,” the member in question wrote. “The woman I had met with twice so far posted pictures of the fires in Israel on Facebook, along with captions crowing things like ‘I’ve never seen such beautiful photos’, and ‘May Allah burn them up, one by one’. Cautiously, I asked if maybe I had misunderstood her, or if Google Translate had gotten it wrong. But no, she was genuinely very happy [about the fires]. I let her know that I felt shocked and hurt by her reaction. [...] And so, with all apologies to the remarkable and valuable New to the Netherlands project: I will no longer be participating.”

Luckily, among the hundreds of interactions between members of De Correspondent and newcomers, the vast majority have been positive experiences. Dozens of participants have let us know they look forward to the next encounter in connection with the next questionnaire. The following round will focus primarily on civic integration.

This report is part of the New to the Netherlands initiative. This project is made possible by support from the Dioraphte Foundation. Thank you to Numeracy Correspondent Sanne Blauw, who oversaw interpretation of the data. And a special thank you to all the newcomers and Correspondent members participating in our project.

—Translated from Dutch by Liz Gorin

More from De Correspondent:

The hairdresser’s amazing comeback (or why everybody needs a Fatima)

It took Maher Mansour four years to build a business in this country as successful as the one he’d owned back in Syria, before he lost everything. His dream wouldn’t have come true without Fatima El Kaddouri. If only every refugee had a Fatima.

The hairdresser’s amazing comeback (or why everybody needs a Fatima)

It took Maher Mansour four years to build a business in this country as successful as the one he’d owned back in Syria, before he lost everything. His dream wouldn’t have come true without Fatima El Kaddouri. If only every refugee had a Fatima.

Seven things the Dutch need to understand about how refugees here feel

Some 300 newcomers to the Netherlands have answered thirty questions asked by members of De Correspondent. It was the largest group interview ever conducted with refugees in this country. Today: the answers to a single question.

Seven things the Dutch need to understand about how refugees here feel

Some 300 newcomers to the Netherlands have answered thirty questions asked by members of De Correspondent. It was the largest group interview ever conducted with refugees in this country. Today: the answers to a single question.

Twenty-four hours in the dorm where students help refugees. And vice versa

One Amsterdam district aims to bring refugees and other residents into contact with one another. At the western edge of the city, there’s an apartment block that 283 Dutch students and 282 refugees call home. I spent 24 hours in this microcosm of society and watched prejudices crumble.

Twenty-four hours in the dorm where students help refugees. And vice versa

One Amsterdam district aims to bring refugees and other residents into contact with one another. At the western edge of the city, there’s an apartment block that 283 Dutch students and 282 refugees call home. I spent 24 hours in this microcosm of society and watched prejudices crumble.