She never set out to be influenced by the western world’s perceptions of people from Arabic countries. “But of course, it happened anyway,” says Romy Cartiere. Before she met her first Arab, she thought they were all proper, reserved, strict individuals. That’s why, a year ago, she was surprised when she first encountered long-haired, pot-smoking, tattooed guys who turned out to be of Arabic descent.

“First I thought, ‘Huh?’ But from then on, it became clear to me: You have to meet actual people. Otherwise, you know nothing.”

“You have to meet actual people. Otherwise, you know nothing

I’m staying with Romy, who’s getting her Master’s in Ecology and Evolution, for 24 hours. She lives in the Riekerhaven “Startblok,” a collection of shipping containers converted into housing, located in the marshy fields along highway A10 in the Amsterdam district of Nieuw-West. The name Startblok literally means “starting block”. Some 283 Dutch students and 282 refugees with residence permits – all of them under the age of 28 – have been living here together since summer.

I have heard from at least three sources that the integration of refugees in Amsterdam Nieuw-West is being handled in a pro-active way. The Startblok recently won a housing innovation award and has inspired similar projects, soon to open in other locations across the city.

The Riekerhaven Startblok in Amsterdam’s Nieuw-West district. Photo by David Hup

The man behind the Startblok idea is Achmed Baâdoud, chair of the Nieuw-West district council, who intends to help newcomers to the Netherlands interact with the Dutch, whatever it takes. Before I stop by in person, I give Baâdoud a call. He hopes that individuals from both groups will become “buddies,” although there’s no rule saying they have to. “It has to come from the heart.”

I’m curious about day-to-day life in the Startblok, which is why I’m going to be spending a day and a night there. In this mini-society, I’ll have the chance to see cultural integration in action. There are a lot of preconceived notions in need of adjustment, about everyone – and on everyone’s part.

You’re more likely to meet if you’re neighbors

The majority of the containers have been converted into studio apartments. Romy’s is located in Hall 3A. Ten Dutch citizens, six Syrians, three Eritreans, and one Gambian live here. They’ve nicknamed their hall “the Mixed Grill platter.” “I thought it was really funny,” Romy tells me. “But it was hard to explain it to the newcomers – they asked if we were planning to barbecue them.”

Hall 3A and James the bunny, at Startblok in Amsterdam. Photos by David Hup

One of Romy’s neighbors is named Ali Awadalla and the other is Abdelmoumen. The Dutch residents and the newcomers are assigned rooms in strict alternating order. “When I found that out, I felt like a guinea pig in some kind of experiment,” Romy says. “But the distribution really does help. The fact that Ali and I interact, is – I think – partly just because he’s my neighbor.”

Romy’s cliché ideas about Arabs were quickly dispatched, and mistaken notions are dissolving on the other side as well. For instance, Aladdin, who comes from Aleppo and has been in the Netherlands for ten months, thinks it would be okay for a man to ask a random Dutch woman what size clothing she wears. Upon hearing he’s wrong, Aladdin reddens from ear to ear. “Oh, shit,” he says.

When Ali was living in the asylum seekers’ center, he only spoke Dutch in the supermarket

Aladdin lives in Venlo and is here to visit his friend, and Romy’s neighbor, Ali. They sit in Ali’s studio, drinking tea. According to Romy, it’s mainly the refugees who have invested time in making their living quarters in the Startblok into something special. You can see this Ali’s room – he’s even plastered one of the walls himself. The room’s heating is turned on; Ali passes Aladdin a package of Dutch wafer cookies. “Do the cookies seem like something you’d like, Ala?” Ali asks him in Dutch.

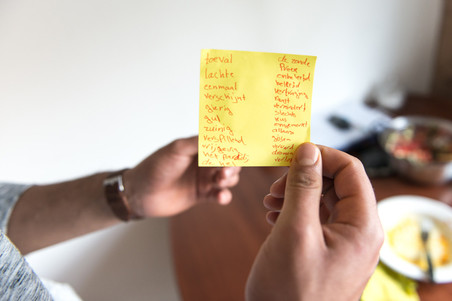

Romy’s neighbor is from the Syrian city of Daraa and arrived in the Netherlands two years ago. In the asylum seekers’ center in Zeist, he pushed and pushed, until they let him start taking Dutch lessons earlier than officially allowed. Today, he can say a good deal in Dutch, although there are certain words he tends to forget. “Gedisciplineerd.” Disciplined. “Geïnteresseerd.” Interested. “Communicatief.” Communicative. Ali pronounces the words carefully, pausing between each one.

Ali is happy to be living in the Startblok. In Zeist, he came across almost no one with whom to practice his Dutch – and he needs to speak Dutch in order to enroll in the economics degree program he has in mind. He only ever spoke Dutch with the cashier at the Plus supermarket back in Zeist: “Please. Thank you. A receipt? No, thanks, don’t need one. Okay, have a nice day. Bye.”

Here, society has yet to start

In the course of my 24 hours in the Startblok, I see how right Romy was: you have to meet people, because otherwise you know nothing about them. And that’s an important thing to remember in this early stage: Society has yet to start here in 3A.

Romy in her room in the Startblok. Photos by David Hup

Sure, Romy and Ali hang out on a regular basis. This time, when they do, Romy talks about the trips she’s taken with AEGEE, an international student association. Plastic event armbands cover her arm halfway to the elbow, each of them a souvenir from a beautiful foreign city. And then Ali says that he’s seen a little of the world, too: Turkey, Greece, and Macedonia, where he spent seventeen days in a forest and was unable to continue his journey. It was cold and he got sick.

“Ali!” Romy exclaims in reply. “Didn’t you sleep in a tent?" Yes, there was a tent, Ali laughs. “But it was still cold, even inside the tent.” He moved on to Albania, Montenegro, Serbia, Austria, Germany, and finally, the Netherlands.

Not all of 3A’s residents are so eager to have contact with others, Romy tells me. While she thinks the three Eritreans in the hall are “really sweet,” for instance, they mostly keep to themselves. And not every Dutch person living in the Startblok is there because of some deep desire to spend all their time with refugees.

“If I’m really honest?” begins Matthias Meuwissen, who is studying commercial economics. “I mostly just like having my own place. I think the concept behind the Startblok is interesting, but I was mainly looking for a room somewhere.”

The first dinner together

Today marks the day that 3A is going to eat together for the very first time. They’ll be dining in the communal living space that each hall has, consisting of two shipping containers put together without a dividing wall. The funny thing, Romy says, is that you can tell how far the community on each hall has come by looking at those two containers. “Some halls are further along than we are and some have a ways to go to catch up,” she explains.

The communal living room and kitchen of 3A. Photos by David Hup

In 3A’s communal room, it looks like the secondhand couches, dining tables, and cupboards have been randomly dumped in the space. The kitchen is sticky. One or two residents cook here, but apparently, no one cleans. The trash can smells like something died in it. “A f*@king mess,” Romy concludes. “Let’s take care of the hygiene first.”

She and Matthias begin scrubbing the kitchen. Then, it’s as if Imad and Abdelmoumen catch wind of it over in the hall itself. They immediately appear in the communal living room, armed with Windex and ready for action. They vacuum. They drag the furniture into a more logical arrangement. Romy begins pulling the stuff she bought earlier today at the Action, a clearance store, from oversized shopping totes: a set of knives, purple and green flatware, and a dustpan with whisk.

There we go, now Matthias can start browning the ground chuck. The buzz of activity begins to draw more of 3A’s residents. Not all of them, but Ali, Jesse, Mohammad, Kenny, Achmad, and Aladdin-from-Venlo turn up. Ali puts on some music on his cell phone – and the conversational volume rises to close to shouting.

Matthias in his room at Startblok. Photo by David Hup

People in this country are always busy

A little while later, as everyone is crowded around the dinner table to enjoy Matthias’ pasta, Mohammad shares some news. “You guys,” he crows, “I passed my Dutch language test.” Cheers and applause all round.

Mohammad had to speak for three minutes, in Dutch, about things he’s noticed in the Netherlands. His observations included that – according to him, anyway – there is only one way to tell someone you love them in Dutch. Nope, but what about Arabic? “We must have a hundred different ways,” Aladdin says. Now the Syrians really start to loosen up: you are my soul, my eyes, the beat of my heart, I will die for you, you are the one to lay a flower on my grave.

Mohammad in his room at Startblok. Photos by David Hup

According to Mohammed, this proves that Syrians treat women better than Dutch men do. The Dutch people protest this loudly. “It’s true,” Mohammed continues. “When you go to a restaurant, who pays for the food? For us, it’s always the man.” Romy: “If you put me on a pedestal, then I’m not your equal.” Matthias: “Do you get it, Mohammad? She doesn’t want to be treated like a princess.” Mohammad blurts out: “But women are princesses, aren’t they?”

The music coming from Ali’s phone is interrupted by an incredibly loud “Allaaaaah Akbar” – the call to prayer. Everybody laughs. Ali messes with his phone for a moment; the music continues. Mohammad, little Mohammad Tlej, who was so excited about his Dutch test, suddenly says that he had higher hopes for the society here at Startblok. “People in this country are always busy, aren’t they?”

He first noticed this after leaving the asylum seekers’ center in Luttelgeest, when he rented a room from an elderly man for two months. One time, the man was sick for three days and even though he had plenty of relatives, no one came to visit. “I was angry and asked him, ‘Why doesn’t your family come?’” My family is busy, the man answered.

You cry every time you hear someone has died

Mohammad used to live in Damascus, where he was studying mathematics. He came to the Netherlands a year ago. One by one, he lost the members of his family in Syria, until there was no one left. “You cry again every time you hear someone has died,” he says. “But then you go on, and you get used to it. My family did everything they could for me, so I could come to the Netherlands. So now I’m going to work hard and take up mathematics again. I want to do things they would have been proud of.”

“My family did everything they could for me, so I could come to the Netherlands

Mohammad stands up and walks to his own studio. According to Ali, he’s going to watch soccer: FC Barcelona is playing Manchester City. Ali gets up to leave as well – he’s going to bed. He wants to get an early start tomorrow so he can spend two hours cramming Dutch vocabulary before heading off to Bagels & Beans, the coffee and bagel place where he works three days a week. The other Syrians say their goodnights as well, most of them because – like Ali – they want to be well-rested for an early start studying.

By around 10 pm, there are only Dutch people left in the communal living area. Then Yasser from Hall 7A shows up and the evening of integration continues. Yasser Rais from Damascus is a friend of Romy’s. Cigarettes are lit and there are bottles of vodka and liqueur on the table. It might have something to do with those bottles that Yasser starts to talk about the war in Syria – although Romy will later say that Yasser talks about the war so much it’s like he’s reporting on a trip to the drugstore.

Yasser remembers how, in Damascus, the teacups would rattle on the tabletop every time a bomb fell nearby. He talks about his mother, who is still in Damascus. He tells us about the army’s conscription policy, which drives many Syrian men to flee the country before their eighteenth birthday. Military service means fighting for President Assad. “What do you do in a situation like that? The only thing you can do is get away.”

The push they needed

The next morning, Romy and I are the only people in the communal living room. Around eleven, Ali strolls in with tea, olive oil, and za’atar, an herb he insists we try on our bread. He’s been working on his Dutch: gedisciplineerd, geïnteresseerd and communicatief roll off his tongue with increasing ease. After Ali leaves, Romy and I do the dishes. The space needs to kept clean from now on.

Ali in his room at Startblok. Photos by David Hup

Imad comes in: Imad Sanan, who was fairly quiet yesterday evening. He speaks only Arabic and is virtually illiterate. Although he’s doing his best to learn Dutch, it’s difficult because he must learn to recognize letters for the first time. He has a sheet of paper with him, with drawings and simple words: cat, rat, fat, hat – that kind of thing, but then in Dutch. He asks us how to pronounce the words on the paper.

A little while later, we hear the sounds of spoken Dutch from his room, clearly coming out of a cell phone. He’s busy practicing; I ask if I can help. He invites me in and shows me a notebook in which he’s copied the Latin alphabet over and over, at least three thousand times.

Imad hasn’t done much in the way of decorating. His bed consists of a bare mattress and a duvet with no cover. He makes me coffee, strong Syrian coffee. Then, as he sets my mug on the table, he says an Arabic word I understand. Afraid. Using his index fingers, Imad traces imaginary lines running from his eyes down his cheeks. I feel for him.

We communicate with gestures and he reads aloud to me from his lesson material. Afterwards, I make my way back to the communal living room, where Romy continues her home improvement efforts. She drapes decorative throws from the Action over the couches and sets coasters on the table. You can feel that from now on, things will be different here in 3A. “That dinner yesterday was exactly the push we all needed,” she says.

This report is part of the New to the Netherlands initiative, in which 300 Correspondent members and refugees will meet for at least six months. They’ll be offering us insight into how newcomers are building new lives for themselves in the Netherlands. This project is made possible by support from the Dioraphte Foundation.

—Translated from Dutch by Liz Gorin and Erica Moore

More stories from De Correspondent:

How one Syrian woman is fighting her way off government assistance

Syrian refugee Zohor Al Musry opened her own karate studio in the Netherlands – just nine months after arriving in the country. A reader sent us this tip after we launched our New to the Netherlands project in October. In the studio just north of Amsterdam, I encountered a resilient woman, proud to be earning her first paycheck here.

How one Syrian woman is fighting her way off government assistance

Syrian refugee Zohor Al Musry opened her own karate studio in the Netherlands – just nine months after arriving in the country. A reader sent us this tip after we launched our New to the Netherlands project in October. In the studio just north of Amsterdam, I encountered a resilient woman, proud to be earning her first paycheck here.

WhatsApp after Paris: 18-year-old Hanna teaches her dad a thing or two

As everyone else was hoisting the French flag on Facebook, a Dutch student named Hanna gave her profile picture the colors of the Syrian flag. The act led to a spirited chat on WhatsApp with her dad, who runs out of comebacks as their conversation goes on.

WhatsApp after Paris: 18-year-old Hanna teaches her dad a thing or two

As everyone else was hoisting the French flag on Facebook, a Dutch student named Hanna gave her profile picture the colors of the Syrian flag. The act led to a spirited chat on WhatsApp with her dad, who runs out of comebacks as their conversation goes on.

A day in the life of a sniper fighting ISIS

In few places has the fighting against the Islamic State been as heavy and sustained as in the Syrian town of Kobani, near the Turkish border. The Kurdish population there slowly but surely took back their streets from the terror organization. Filmmaker Reber Dosky made the trek to Kobani and came back with a unique portrait of a sniper in a battered city.

A day in the life of a sniper fighting ISIS

In few places has the fighting against the Islamic State been as heavy and sustained as in the Syrian town of Kobani, near the Turkish border. The Kurdish population there slowly but surely took back their streets from the terror organization. Filmmaker Reber Dosky made the trek to Kobani and came back with a unique portrait of a sniper in a battered city.

This is the Berlin Wall of our time

Syrian refugees continue to flee the country in droves, but a solution to the conflict there remains elusive. Why? The answer may seem surprising, but our greatest obstacle on the road to peace in the world could well be veto rights in the United Nations.

This is the Berlin Wall of our time

Syrian refugees continue to flee the country in droves, but a solution to the conflict there remains elusive. Why? The answer may seem surprising, but our greatest obstacle on the road to peace in the world could well be veto rights in the United Nations.