This headline flashed on the website of the Dutch national broadcaster: "One glass of alcohol is one too many." Drinking more than one glass a day increases your chances of dying early, the report stated.

This article, which appeared online in April 2018, cited a study published by the renowned medical journal The Lancet, for which 83 studies referencing a total of some 600,000 subjects had been aggregated. Impressive evidence, I thought, but correlation is not the same as causation. Drinkers and non-drinkers must be different in other ways as well. And these differences could explain why the first group tended to die younger.

The same thing was spotted by Vinay Prasad. A US doctor and researcher, Prasad knows everything there is to know about evidence-based medical theories. He delved into The Lancet study, then tweeted brusquely: "A team of scientists prove [sic] the human thirst for bullshit science and medicine news is unquenchable."

This comment was elucidated in a thread of more than 30 tweets. Prasad referenced publication bias: only studies that find a significant relationship are published. He argued that alcohol use was monitored for only a short time by these studies, and that while a higher mortality risk was found among beer drinkers, this risk had turned out to be minimal in wine drinkers. It wasn’t so much the alcohol, Prasad suggested, as the lower incomes of beer drinkers that was unhealthy.

I came to the conclusion there was nothing wrong with a tipple (or two).

The same mistakes

There is an idea that pops up time and again: a lack of knowledge is the problem that limits understanding, and more knowledge is the solution. When climate scientists publish temperature graphs, or journalists fact-check politicians, or ministers trot out economic figures in a debate – every one of them is trying to combat mistakes with yet more information.

For a long time I believed that knowledge was the solution. As Numeracy correspondent, I wrote about bad polls, margins of error, the nuances of correlation and causality. My articles tried to explain how to recognise these kinds of errors, to deter such misunderstandings in the future. I saw myself standing in a long line of writers who wanted to raise awareness about this topic.

Not much has changed. In 1954, Darrell Huff outlined the principal pitfalls with numbers in his book How To Lie With Statistics. "The crooks already know these tricks; honest men must learn them in self-defence," Huff wrote. His book became a roaring success, selling more than 1.5 million copies of the English version alone. But the same mistakes are being made today: unrepresentative polls still get far too much attention, and health stories confusing correlation with causality appear in the news almost daily.

People are still lying with statistics.

Obviously, making sense of statistics will sometimes require expertise. Not everyone has learned how to calculate a confidence interval, nor to fully grasp how an algorithm works. But many of the mistakes that Huff exposed were easy to spot, even without knowledge or training in statistics. False conclusions about numbers keep slipping past scientists, journalists, politicians and readers.

And past me. I was outraged when I read about a study which alleged that female software programmers were undervalued by their colleagues. Later it turned out that the media had misinterpreted the study; programmers were not nearly as sexist as the reporting had suggested.

Over and over again, I fell for the same mistakes that I had discussed at length in my articles. It was only when I encountered the work of law professor Dan Kahan, that I started to understand why. The problem was not to do with lack of knowledge. This is about psychology.

Culture eats data for breakfast

For years, Dan Kahan has investigated how beliefs, culture and values influence thinking. In one of his experiments participants were presented with a table of results from a fictitious study of skin cream. One group was shown figures which reported an increased skin rash; the other group saw figures which showed the rash had decreased.

Kahan asked participants whether the cream helped with the rash, or made it worse. To answer, participants had to make a tricky calculation from the figures in the tables. The people who had scored better in an earlier maths test tended to come up with the right answer. So up to this point, the experiment confirmed what you’d expect: if you have a better understanding of numbers, you will get closer to the truth.

But there were two further groups. These participants were given the same tables of figures, but this time the data was described as relating to a controversial topic in US politics: gun control. The figures were attributed to a fictional experiment in stricter legislation. The question to answer was: does crime go up or down as a result of the new law?

The answers were as different as day and night from those given by participants in the skin cream experiment. The participants who were good at maths performed worse than before. The figures were exactly the same as those for the supposed skin cream experiment, but now the participants gave the wrong answers.

Your brain works like a lawyer

The explanation for Kahan’s results? Ideology. Irrespective of the actual figures, Democratic voters who identified as liberal (and, normally in favour of gun control) tended to conclude that the stricter measures had reduced crime. For conservative Republican participants, the reverse happened: they calculated that tighter gun control did not work.

These answers are no longer about the truth, Kahan argued. They demonstrate concern for protecting your identity or belonging to your "tribe". And those people who were skilled at maths, Kahan also found, were all the better at this. Often completely subconsciously, by the way. In reaching their answers, it was their psyche that played tricks on them.

Time and again, Kahan saw this outcome from his experiments; when people know more facts or have more skills, they have more resources from which to draw when deluding themselves. Our brain works like a lawyer; it will find the arguments to defend our convictions, whatever the cost or the facts.

This habit is maintained even if your convictions change or seem too contradictory. You can believe one thing at one point, then another thing later on. There are conservative farmers in the US, for instance, who deny the existence of climate change but take all kinds of measures to protect their business from the effects of a changing climate.

This seems irrational but it isn’t, as Kahan explains.

The stakes can be high if you change your convictions. A farmer who is suddenly convinced and believes in climate change may be given the cold shoulder by his family, in church, at the baseball club. He puts a great deal on the line but gets nothing in return. It isn’t as if he’s going to save the climate on his own. The truth will have to wait.

Fallible feels good

In just the same way, the truth had to wait when I read about the alcohol study. I could just continue drinking, I concluded. Vinay Prasad’s tweets had only confirmed that belief. Or that’s what I thought.

When I looked again at Prasad’s tweets, I saw that nowhere did he suggest that drinking was not harmful. His argument is simply that the conclusion of this study was flawed.

As Kahan found, I had chosen an interpretation that fitted my "tribe". When I meet friends, we drink a few glasses of wine or beer. That’s what we do. Should I stop doing this? I’d rather not. My interpretation wasn’t necessarily right, but it felt right. I thought I was good at this kind of thing because, from my work, I understood immediately the arguments that are made against this type of study.

My brain, too, had worked like a lawyer.

Everyone is susceptible to these kinds of psychological pressures, including Kahan. In an interview with journalist Ezra Klein in 2014, Kahan mentioned that he has learned to assume that he will make the same mistakes personally that he has observed from his research. He, too, protects his identity with "facts".

It’s a sad observation.

Not least because when I hear terms such as fake news, alternative facts and post-truth, I always thought of these as problems for others. I believed that people who ignored facts are simply putting their own interests above the truth. Unlike them, I saw myself as someone who took facts seriously. But now I saw that I have my own alternative facts. Just like everyone else.

Know your blind spots

Let’s be clear: there are plenty of issues where the psychological bias revealed by Kahan’s study won’t play a part. Most people will have a neutral reaction to numbers concerning something like skin cream. But it’s the numbers about which you do feel something – racism, climate change, Covid-19 – that are susceptible to bias.

Exactly the topics that play an important role in elections.

How can we avoid making these mistakes? The realisaton that you’re fallible, Kahan told Klein, is already a step in the right direction: "That gives you a kind of humility." The researcher also confided that within his own circle, he’s started to look for differences of opinion. In other words, I should talk to malt beer drinkers – and teetotalers – more often.

But the best response? Kahan didn’t know that for a long time. His research showed that the psychological processes existed, not how you could fight them. Until, by accident, he stumbled upon a solution.

In early 2017, Dan Kahan and his colleagues published a new study. He had asked around 5000 people questions to measure their "science curiosity" for a project about science documentaries. How often did the respondents read books about science? Which topics interested them? Did they prefer reading articles about science or about sport?

He threw in a few questions about the respondents’ political persuasion and their ideas about climate change. For example: "How much risk do you believe global warming poses to human health, safety, or prosperity?" In the same way that Kahan had included a maths test in previous experiments, he was now measuring "science intelligence" – a skill that was supposed to help when interpreting information about climate change.

Again, Kahan saw what he had found in earlier research: liberal Democrats perceived more risk from global warming than conservative Republicans. The more "intelligent" the respondents, the bigger the difference in opinion between the two groups.

But what if instead of groups categorised according to intelligence, Kahan measured according to curiosity?

When Kahan looked at the correlation between curiosity and perceived risk from climate change, he noticed an interesting tendency: the Democrats and Republicans still held to their different opinions, but the more curious the respondent, the greater the risk they perceived from a warming planet. Irrespective of political convictions.

Kahan had found a potential antidote: our best defence is curiosity.

Curiosity trumps identity

Why did curiosity play a part here? In a follow-up experiment Kahan presented respondents with two articles about climate change; one confirmed the risks, another was sceptical.

The headlines of both articles were suggestive. One was worded in such a way as to appear novel: "Scientists Report Surprising Evidence: Arctic Ice Melting Even Faster Than Expected." The other headline suggested no such surprise: "Scientists Find Still More Evidence that Global Warming Slowed in the Last Decade."

He asked the participants to choose which article to read. And here, the power of curiosity became evident. The curious types didn’t choose the article whose headline accorded with their convictions: they preferred the challenging one. For these respondents, curiosity was a stronger influence than personal ideology.

Suddenly, the remedy for our psychological barriers seems simple: look for new information. Or in writer Tim Harford’s phrase: "Go another click." Don’t just read articles that confirm what you already think. Instead, find out information that might surprise you, which goes against your beliefs, or makes you feel angry, desperate, uncomfortable.

I’ve put this to the test. After I noticed that I felt a little too good about the conclusion that alcohol was fine, I started to google, which led me to all kinds of studies into a causal link between alcohol and cancer risk. One experiment involved a baboon who developed liver disease as a result of alcohol consumption, for instance. A meta-study found a linear correlation between alcohol and breast cancer risk.

What became clear to me is that experts have long agreed on the adverse effects from drinking. The Dutch Health Council has, since 2015, recommended drinking no more than one glass of alcohol a day. For a reason. As anyone who has woken up with a hangover could attest, you don’t need scientific proof to realise that alcohol is probably not very healthy.

Should I stop drinking then?

Those who are certain, lack curiosity

Kahan’s research into curiosity is still in its early stages. His experiments need to be repeated, and tested. Even if re-running them brings the same results, his conclusions may yet be invalidated by new studies.

Research into alcohol is much more advanced than Kahan’s research into curiosity. If you google "meta-study" (a study into studies), you’ll find that many alcohol studies come to the same conclusion. The causal link between breast cancer and alcohol consumption is now proved. Research into alcohol is arriving at the point already reached by scientists who examined the stack of studies into the impacts of smoking: we know enough.

But even that research into alcohol is never definitive: that’s the nature of science. You can’t always disentangle correlation and causality in alcohol studies; research on animals is not the same as research on people, after all. And it’s unclear how much alcohol you can drink before it becomes bad for you.

That’s the point of research: it doesn’t promise certainty.

It turns out that, psychologically, uncertainty is something we don’t handle very well. This is why people with firm convictions dominate talk shows, political debates and newspaper columns. "I’m sure about this," every one of them will say: "let me tell you how the world works". But people who are certain lack curiosity, by definition. If you cling to your convictions, you’re not likely to be receptive to new information. If we want to be informed – properly informed, then we have to embrace uncertainty.

Don’t let yourself be paralysed by uncertainty, though. At some point you’ll have to decide. Despite uncertainty, you can make a choice. For example: should you have a drink? Or should you drink less?

Vinay Prasad wrote something else in those tweets. When it comes to things like coffee and alcohol, he cautioned, "we may have to make decisions the same way we decide how often to go to the bathroom or movies". Based on common sense.

Based on common sense, I choose to be curious. And to drink one of those malt beers tonight.

This article is an excerpt from The Number Bias - How Numbers Lead and Mislead Us, published by Sceptre. You can also read the Dutch version of this article.

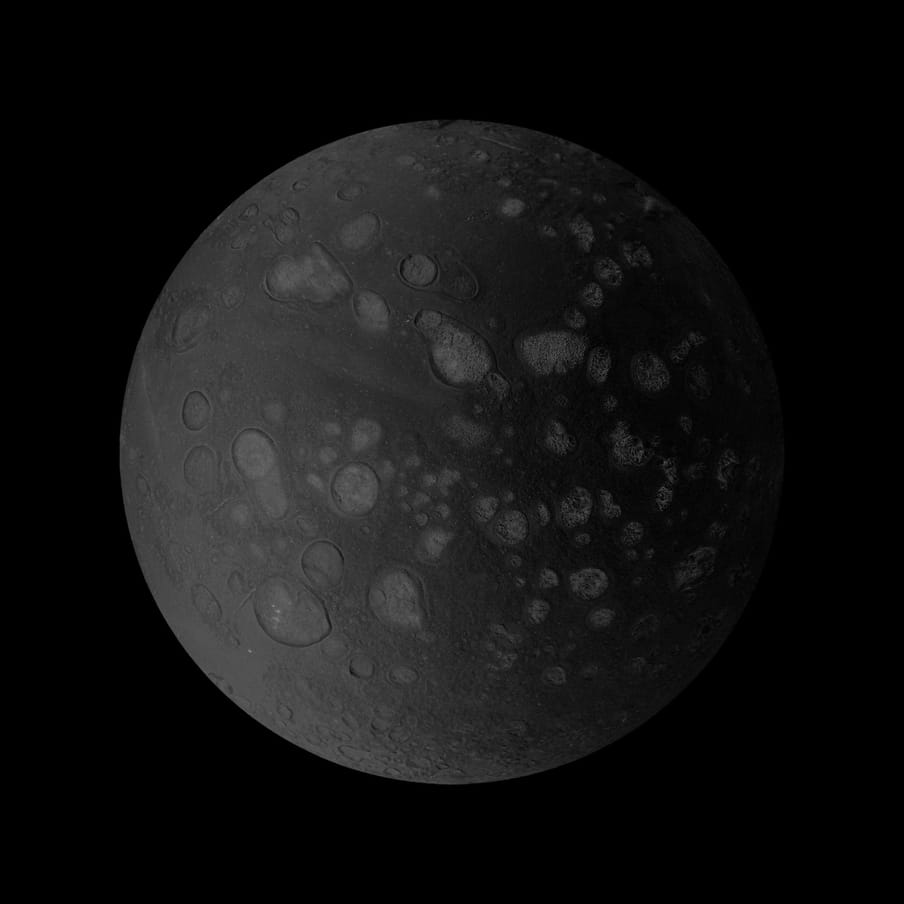

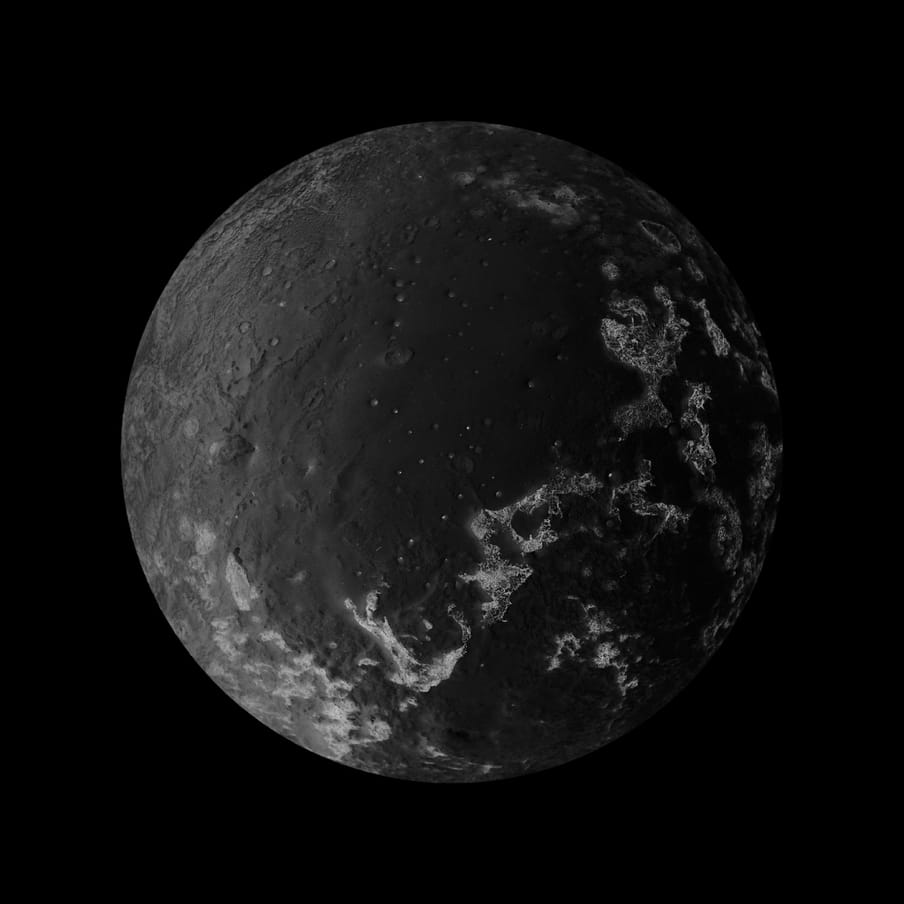

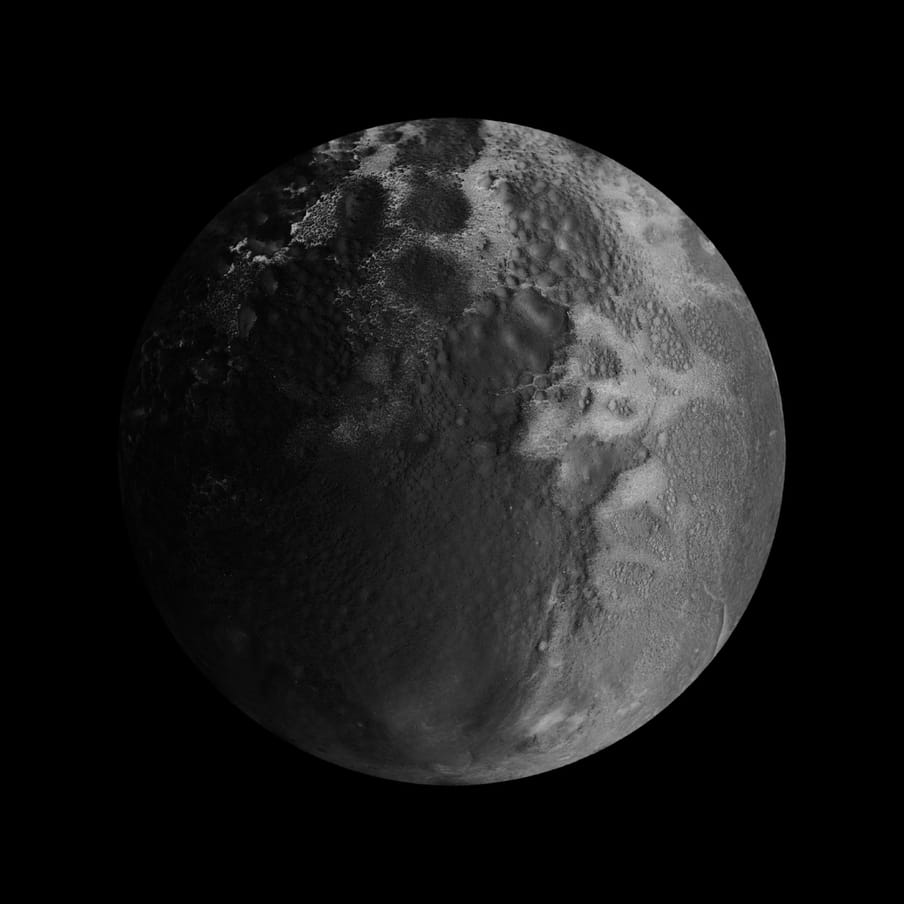

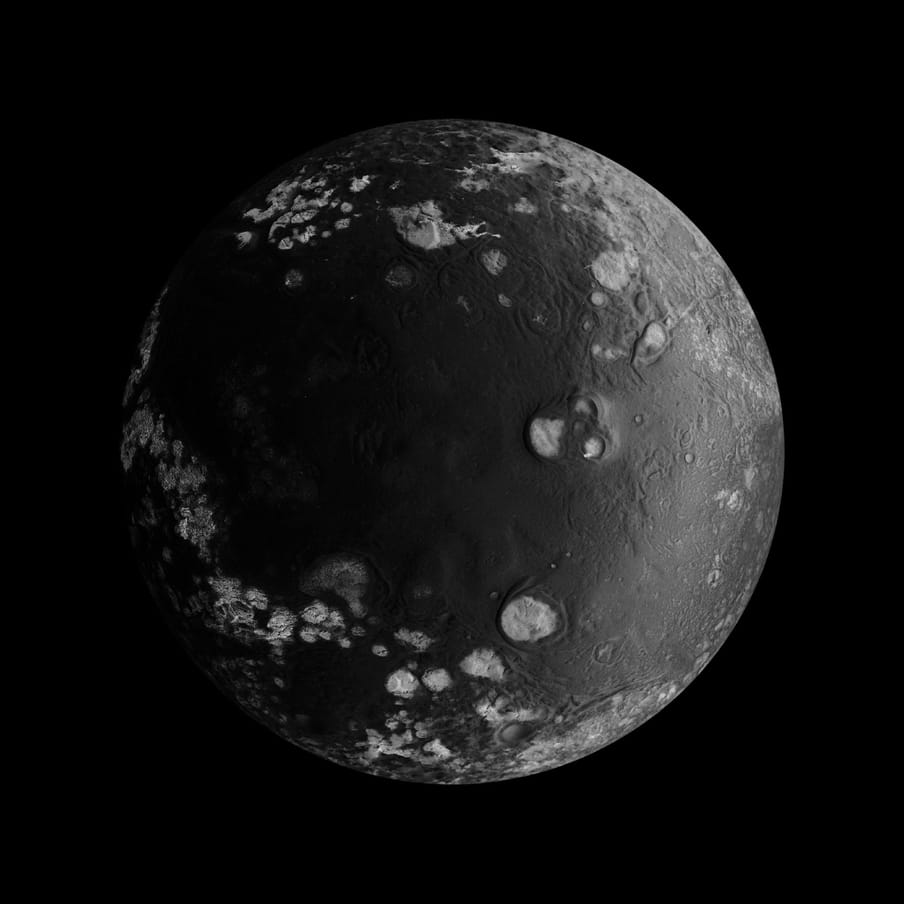

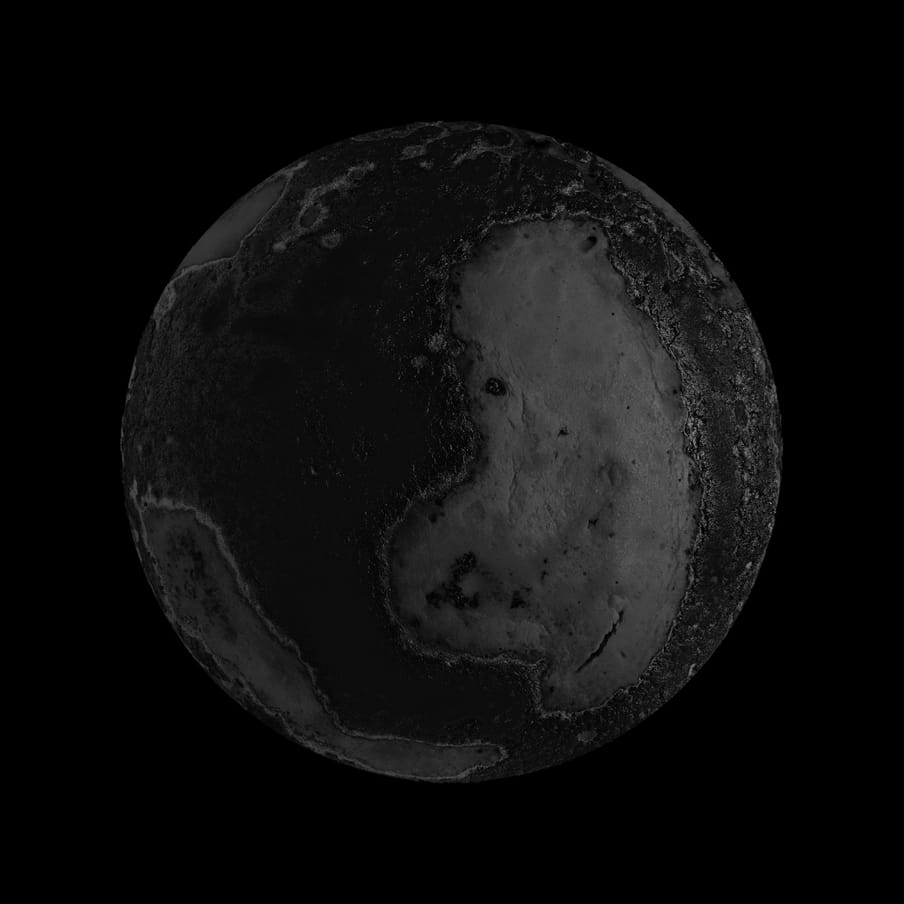

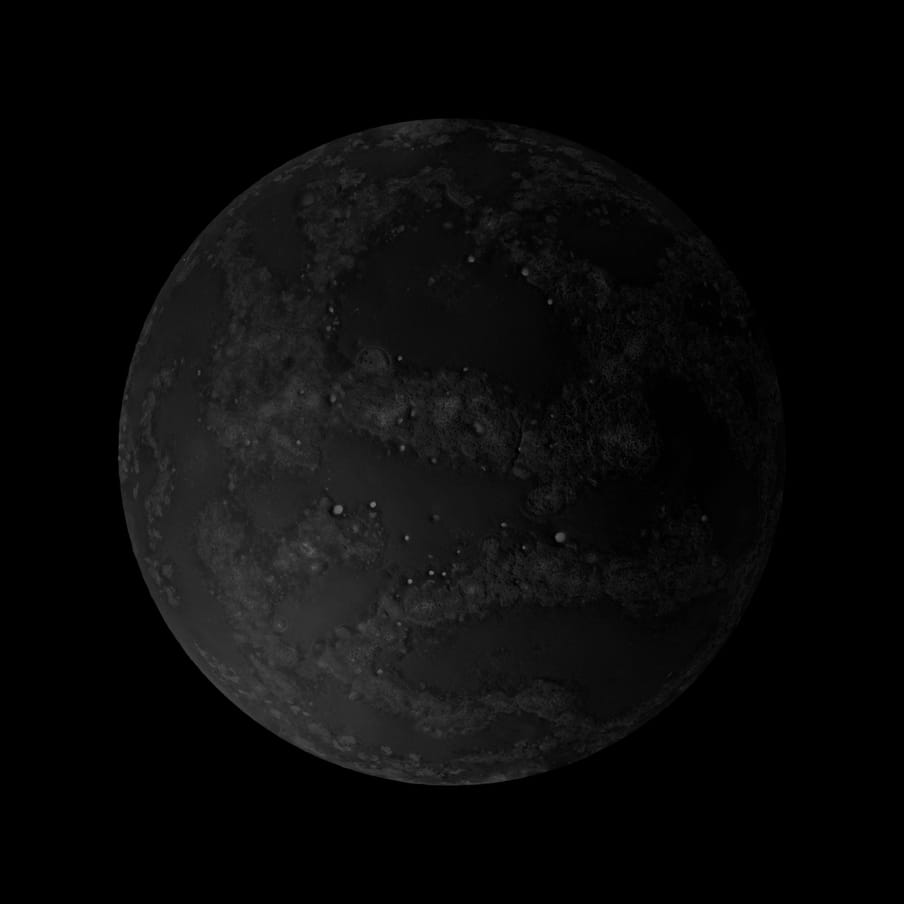

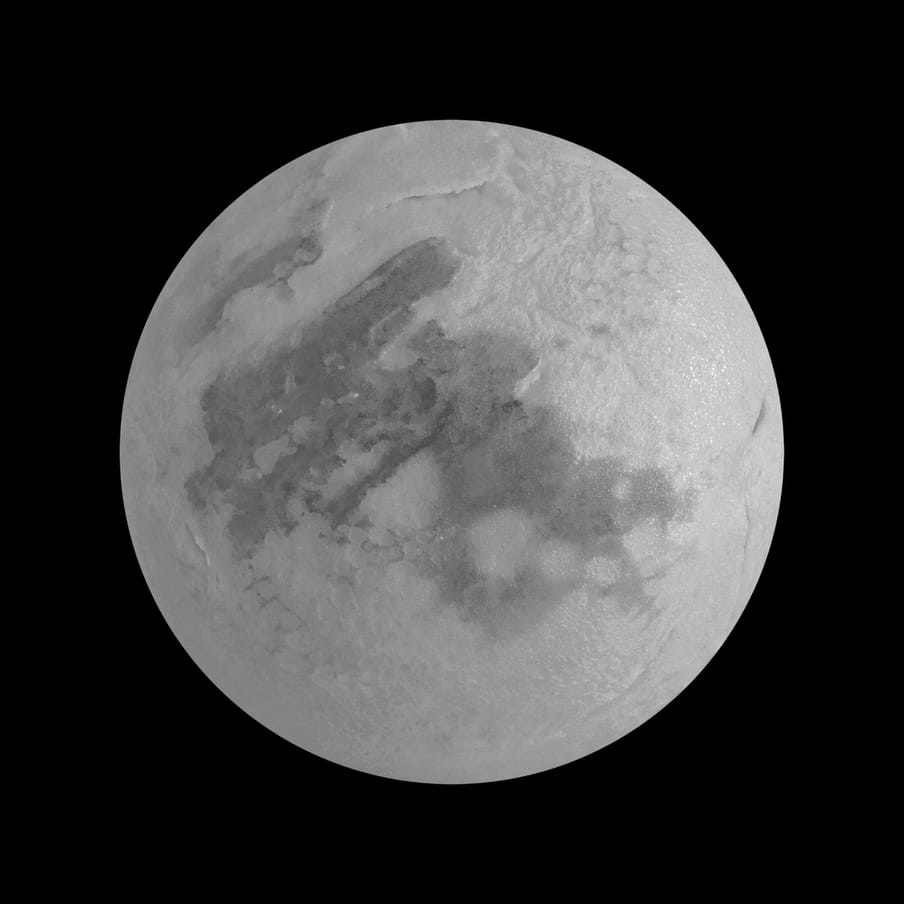

About the images

Seeing the images in this article you might have thought: Wow, what beautiful lunar landscapes! Well, these were actually pancakes. Visual artists Robert Pufleb and Nadine Schlieper show in their book ‘Alternative Moons’ how a crêpe is sometimes hardly distinguishable from a celestial body. Just as the lie became an alternative fact, the pancake became an alternative moon. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

Seeing the images in this article you might have thought: Wow, what beautiful lunar landscapes! Well, these were actually pancakes. Visual artists Robert Pufleb and Nadine Schlieper show in their book ‘Alternative Moons’ how a crêpe is sometimes hardly distinguishable from a celestial body. Just as the lie became an alternative fact, the pancake became an alternative moon. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Want to stay up to date?

Follow my weekly newsletter to receive notes, thoughts, or questions on the topic of numeracy.

Want to stay up to date?

Follow my weekly newsletter to receive notes, thoughts, or questions on the topic of numeracy.

Dig deeper

In praise of doubt: we should be less sure about everything. Right?

Talking heads spout forth online and in the media, each new opinion seemingly more assertive than the last. But the world is full of uncertainty. If you want to make better decisions, dare to doubt, embrace unpredictability and learn to think like a fox.

In praise of doubt: we should be less sure about everything. Right?

Talking heads spout forth online and in the media, each new opinion seemingly more assertive than the last. But the world is full of uncertainty. If you want to make better decisions, dare to doubt, embrace unpredictability and learn to think like a fox.