Hi,

Dorothy Parker, that’s who I’m blaming if I have a breakdown over my debut newsletter. "She looked as new as a peeled egg," Parker describes a new bride in her short story Here We Are. Show me a droller way of capturing how strange and faintly repulsive new things can be.

Maybe I should pop one of those emergency anxiety pills before the palpitations get worse?

Oh come on. You’re not sick - just nervy.

No no no, don’t fall for that. You know how this ends – with you locked up in a room bawling your eyes out. Take the damned pill.

Over a lifetime of depression and anxiety – 18 years now since my first diagnosis – I’ve got used to a few things. First, the perpetual wait for an "episode" triggered by the smallest germ of self-doubt. Second, the constant tug of war between paranoia and bravado. And finally, in consequence, treating life as a series of questions with no expectation of certainty.

Yet recently I’ve found my questions acquiring an unfamiliar colour. I am no longer obsessed with the side effects of pills or the relative efficacy of psychoanalysis over cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT is a short-term, goal-oriented form of therapy that aims to change people’s patterns of thinking and behaviour). Instead, I have taken to wondering about something more fundamental – if my condition can really be boiled down to what my doctor and therapist tell me it is: a sickness.

Denying your sickness complete power over you is a political statement

I have begun to suspect that my talent for blowing up every moment into a crisis has a higher purpose. Maybe it gives me access to a secret world that the “healthy” can never find? If that’s what my sickness really is – the ability to see a mountain, however forbidding, where others can only see a molehill – would I want to give it up?

Shreevatsa Nevatia, author of the bipolar memoirs How to Travel Light, is a bankable source of wisdom on such messy issues. He writes about his conversations with K, a schizophrenic, who has learnt to “enjoy her illness”.

K sees and feels things that don’t exist in the way most people understand existence. In the eyes of medical science, this makes her a malfunctioning human who needs to be fixed. But that’s not how she sees herself.

“I’m more at peace with my own suffering as a cost of receiving access to other worlds,” she says. “They come to you at [a] price. You see scary things, yes, but at the end of it all, you see a world that is beautiful, one that is not accessible to others.”

K doesn’t believe her schizophrenia is a disability. "I think of myself as a super able person," she says.

This interpretation of sickness has profound implications for the relationship between the sick and the rest of the world. When the sick refuse to be pigeonholed into that four-letter word, it calls for a rethinking of everything – to begin with, the never-enough superstructure of healthcare, and who needs it more than others.

Getting the world to acknowledge your invisible sickness can be harrowing

K’s flights – as a child her hallucinations took her to Kashmir, even though she has never really been there – are not just a salve for her. Her magical spin to her sickness is also a way to give society permission to shift its focus to those who have not yet managed to turn their demons into something beautiful. (Whether society cares is a different story.)

Denying your sickness complete power over you is a political statement. Agreeing to split your share of the meagre sympathies, and resources, earmarked for those who live with disability – if not leave the queue altogether – is an act of enormous benevolence.

But K’s story also raises its own questions. As a high-functioning depressive, "super able" is a badge I wear with pride. And there are times when I regret it. Getting the world to acknowledge your invisible sickness can be harrowing. On top of that, if you don’t look or act sick – all sickness is also a performance, I have discovered – and pack in 12-hour work days without complaining, you risk playing right into the hands of those who want to deny your sickness altogether.

Is it fair to invalidate the experience of sickness by calling it not-sickness? Who has the right to do that? Only the one who lives with it?

What if our tools of transcending our suffering are appropriated by those who whisper, "It’s all in your head"?

Near the weekend, I saw an angry tweet from Vijay Nallawala, who runs a bipolar peer-support group in India, reminding me that this is a real danger.

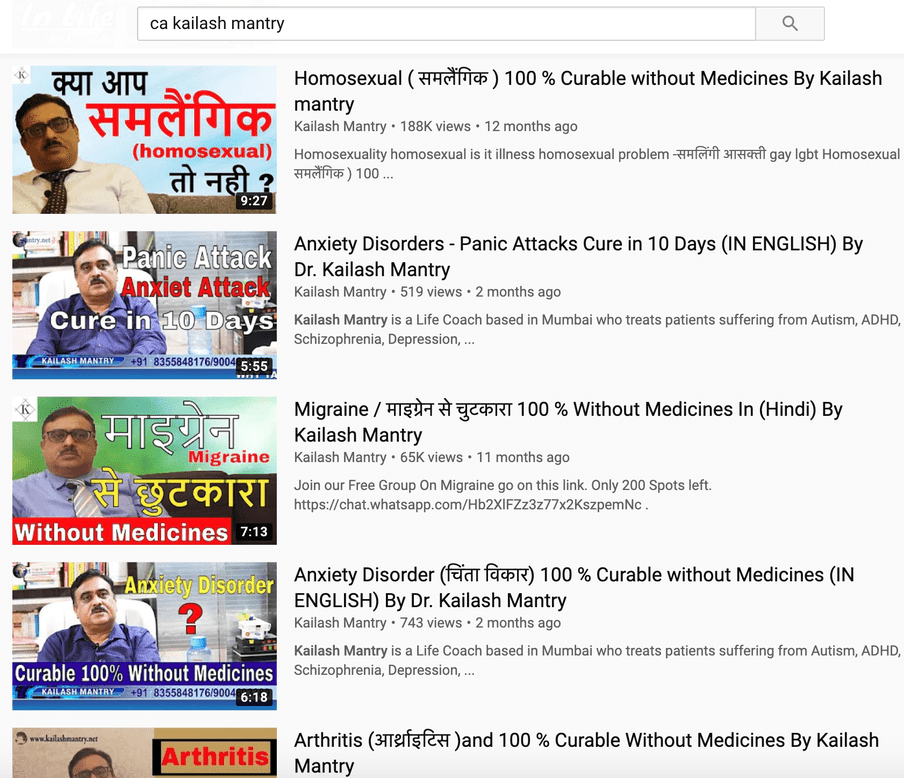

The subject of the tweet was a chartered accountant and self-styled life coach who has become a YouTube mini-sensation by claiming that he has invented rapid, guaranteed cures for everything from depression to bipolar (he also calls homosexuality a “mental illness” and promises “100% cure”), without any medicine.

This miracle worker will have you know that all mental illnesses are caused by one thing alone: "In one line, people who are not at ease with themselves get these problems.” (Emphasis mine.)

The fact that his videos (in Hindi) have had tens of thousands of views proves how easy it is to turn complex psychological conditions into clickbait by preying on people’s confusion and lack of awareness, and our collective desire to wish them away with easy DIY fixes. He may be a crude embodiment of this desire, but you can see the same streak – the idea that "you are what you think" – in some well-respected academics quoted by reputable newspapers.

After watching a couple of minutes of one video, I was suddenly filled with gratitude and affection for my doctor and therapist - brave warriors making sickness real via antidepressants and colouring books.

What do you think? How should someone make sense of their sickness? Strictly follow the definitions given in diagnostic manuals? Or to each their own, even if that means learning to live in a fantasy?

An update on my next investigation

My first series for The Correspondent will be an exploration of guilt and how it is shaping our world. Why guilt? I attempt to answer that in my first callout.

If you are a member of The Correspondent and can help me with my research, or you want to introduce me to somebody who can, please give me a shout via email or Twitter.

Thanks for reading. Until next time.

Tanmoy

(PS: I dodged the pill for today.)

If any of the issues raised here resonates with you or someone you know, please know you don’t have to suffer in silence. Seek help.