October 4, 2011, should have been the turning point in the Syrian civil war. At the time, the conflict was still contained: President Assad had only been fighting the Free Syrian Army for a few months. Chemical weapons had not yet been deployed. The Islamic State did not yet exist. Millions of people had not yet fled the country.

The turning point should have taken place in New York, in the United Nations Security Council – the world’s highest body tasked with peace and security. On that day in October, the council voted on a resolution that condemned the violence of the Syrian government against its own people, and paved the way for further sanctions against the regime. In short, the resolution would smother the flames of war.

But October 4, 2011, was no turning point.

The war raged on. The death toll grew. February 4, 2012 (7,500 dead) was no turning point. Nor was July 19, 2012 (13,000 dead), nor May 22, 2014 (150,000 dead).

On all these dates, the international community tried to take a stand to end the war in Syria. And on all these dates, one thing stood in the way.

Illustration by Aimée de Jongh

The veto.

In the U.N. Security Council, five countries have the right to veto proposed resolutions: the United States, Russia, China, France, and the United Kingdom. And with it, these countries have the power to block every international mission in conflict zones.

Over the past several months, we interviewed dozens of experts about the role of the United Nations in wars. And every time we talked about ideas for the future – when we discussed smarter, better, or faster ways for the U.N. to intervene in conflicts – the conversation ended the same way.

Expert: “That’s all very nice, but it will never happen.”

Us: “Why not?”

Expert: “The veto.”

Us: “Oh, right, the veto…”

In our search for the future of peacekeeping missions, the veto is like a wall we keep running into. And we’re not the first to slam into it. For as long as the U.N. has existed – 70 years in 2015 – people have railed against the veto. It’s enough to make you throw up your hands in despair.

But despair won’t get us anywhere. So we decided to thoroughly examine the veto. Why was it ever adopted, how is it used, and is there a way to do things differently?

Our conclusion: the veto is indeed a wall. But a very specific one. The veto is the Berlin Wall of our time.

A short-lived league

It’s hard to imagine now, but once upon a time, the veto seemed like a good solution to a problem. To understand that, we have to go back to the end of World War I. In 1920, the winners of that war (led by France and the U.K.) founded the League of Nations: an organization designed to prevent a second world war.

The League’s most powerful body was the Executive Council, whose permanent members were the major powers of that time. To reach a decision – to condemn violence, for example, or to impose sanctions on a country – every member of the Council had to agree. That made the League slow as molasses. Almost never did everyone agree on an issue.

What’s more, there was one major player missing: the United States. The U.S. Senate voted against membership in the League, which limited the organization’s power from the start.

Unsurprisingly, the League fared poorly. After the rise of the Nazi party, Germany left the alliance, followed by Japan and Italy. The Soviet Union was thrown out, because it had invaded Finland without permission.

And that second world war? It happened anyway.

A bus with stop buttons

Enter the United Nations. The world’s second attempt to create a group that would achieve world peace. Once again, the winners of the war took the initiative: this time, the Allies.

To avoid the League of Nations’ fate, the founders decided to set up the U.N.’s executive council differently. More decisive. Faster. More effective. And so the new Security Council, as it was named, was given an inventive form.

The best way to picture the Security Council is as a bus driving down a bumpy road. Its destination: world peace. The bus has five seats – the permanent seats on the Security Council – occupied by the winners of World War II: the United States, China, Russia, France, and the United Kingdom. There are also ten places to stand in the bus – the Council’s non-permanent seats – where new countries may stand every two years.

Illustration by Aimée de Jongh

To decide what direction the bus will take, nine of the fifteen seated and standing passengers must vote for it.

All the countries that don’t fit inside the bus drive in a long caravan of vehicles behind it. Their speed is determined by how fast the bus travels toward global peace.

But something had to be done to ensure that the world’s superpowers were willing to sit in the bus in the first place, and to keep them from leaving it at the slightest provocation (as happened in the League of Nations). So the U.N.’s founders decided to install a stop button at each of the five seats: the right of veto. That way, the seated superpowers could control the speed of the bus themselves.

And that’s why to this day the United States, Russia, China, France, and the United Kingdom can block any decision the U.N. Security Council makes, and thus determine U.N. policy on international peace and security. They are called the P5: the permanent five seated on the bus.

One big veto party

Illustration by Aimée de Jongh

The stop button turned out to be a winner: unlike the League of Nations, the United Nations is still around – and every major country is still in the club. But the right of veto gifted to the superpowers also had a downside.

That became painfully evident shortly after the U.N. was founded. To protect and expand their own spheres of influence during the Cold War, the U.S. and the Soviet Union meddled in every conflict. In proxy wars in Cambodia, Angola, and Vietnam, the two superpowers were diametrically opposed – and thus always at odds on how to intervene. Meanwhile, the superpowers could carry on as they pleased: the United Kingdom protected the apartheid regime in South Africa, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, the U.S. sent its armed forces to Panama. And the U.N. was powerless to stop them. Plans to intervene were invariably vetoed by one of the superpowers. The Security Council was deadlocked.

What’s more, it was nearly impossible for new countries to become a member of the U.N. The Soviet Union played the veto card every time a new country petitioned to join, in order to maintain the U.N.’s precarious East-West status quo.

In total, the P5 exercised the right to veto 199 times during the Cold War. Nearly half the vetoes were cast by the Soviet Union.

Source: Dag Hammerskjöld Library

The end of the Cold War around 1990 meant the start of a new era in the Security Council. At last the veto would stop being used to fight the East-West feud. At last the Security Council would be able to work as one to prevent and resolve conflicts.

So you’d think.

But the fall of the Berlin Wall did not vanquish the veto, as the graph below shows.

Source: Dag Hammerskjöld Library

The United States kept blocking sanctions against Israel. Russia twice stopped the U.N. from condemning its annexation of the Ukrainian Crimea. And nowhere is the Security Council’s incompetence more clearly visible than now in Syria. China and Russia block every action against the regime of President Assad.

Of course we can’t say with certainty what the world would look like if no one ever cast a veto. We don’t know whether the war in Syria would have been stopped if the U.N. had intervened early on. But what we do know is that when the U.N. gets involved, it usually means fewer civilians die. That peace often lasts longer when the international community intervenes. And that watching from the sidelines while so many victims die is morally unacceptable.

When we compare the two graphs again, something else jumps out at us. The veto has been used far less often since the Cold War: “only” 35 times. That sounds like good news, but it isn’t that simple. Because the veto has picked up a negative taint – “blood on your hands” – the P5 use the threat of a veto instead, known as a pocket veto. The five countries just have to move a hand in the direction of the stop button, and a topic is scrapped from the agenda.

And so the veto still has the world in a stranglehold.

Lynched by an angry mob

It’s time to take a trip back in time, to the 5th century B.C. There was no United Nations yet, but the veto was already in use.

You see, the right of veto was invented around this time, in the Roman Republic. Here, the highest power lay with the elite Senate – a kind of Roman Security Council. The veto – Latin for I forbid – was invented as a way of limiting the Senate’s power. The tribunes, who represented the common folk, could veto the senators’ decisions. And if a senator ignored the people’s veto? As a rule, he was lynched by the crowd.

In its origins, then, the veto is a form of democratic check, a way to hold the powerful Senate accountable. But in the Security Council, it’s precisely the most powerful countries – the P5, the senators of today – who hold the right of veto. So instead of a democratic tool, the veto has become a way for the superpowers to hold on to their power, to maintain the status quo.

And the older the U.N. gets, the more that status quo in the Security Council chafes against reality. Because today, in 2016, are the P5 even the world’s superpowers anymore?

The answer, of course, is no. The five countries that were granted the right of veto after World War II are not nearly as powerful in the 21st century. They’ve gotten competition from countries like Brazil, India, Germany, and Japan. But what should today’s Security Council look like, then?

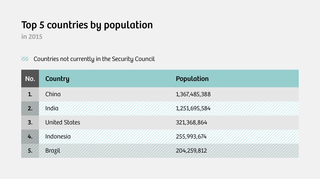

If you look at population, then this should be the Security Council’s P5:

Source: CIA World Factbook

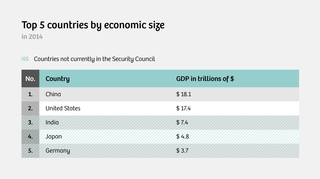

If you look at economic strength, this would be the P5:

Source: CIA World Factbook

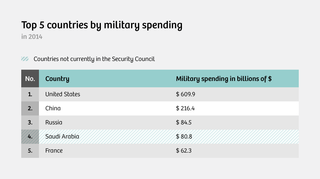

Or this, if you look at military spending:

Source: Sipri

And of course there are 1001 more ways to come up with a top five. You could look at where the most wars occur; then African and Middle Eastern countries should be better represented. And who says there has to be a top five in the first place? The Security Council could also be expanded – with permanent or non-permanent members – to give more countries influence.

Would you like to sit down? I’d be happy to stand

So, actually, the world has two questions on its plate: who should be in the U.N. Security Council, and should they have veto rights or not?

To answer these questions, the U.N. created a working group way back in 1993. The group has the longest U.N. name ever: the Open-Ended Working Group on the Question of Equitable Representation and Increase in the Membership of the Security Council and Other Matters Related to the Security Council.

But despite plenty of meetings, the working group hasn’t yet found a solution to the problem. And that isn’t so surprising.

To understand just how hard it is to find a solution, let’s go back to our bus, where the United States, Russia, China, France, and the United Kingdom have been occupying the seats with stop buttons for decades.

Illustration by Aimée de Jongh

A long line of traffic is piled up behind the bus: the other U.N. member states. The cars in that line are highly disgruntled. Everyone agrees it’s unfair that only five countries may have (and keep) a seat on the bus. And for that matter, those guys need to lay off the stop buttons. The rest of the world wants to keep moving forward.

And so the majority of those cars have united in the ACT Group – Accountability, Coherence, and Transparency – and devised a code of conduct for stop button use. They propose making the button off limits in the event of “mass atrocity crimes,” and when the button is used, the one who pressed stop has to explain just exactly why.

But there are plenty of other groups calling for even greater reform. They’re tired of being stuck behind the bus. The catch: these countries are at odds as to which of them should be allowed to join (or replace) the ones in the bus.

- For example, the G4 – India, Brazil, Germany, and Japan – also want to sit down. They promise that for now, they won’t press the stop button.

- The C-10 wants two seats for African countries – with stop buttons – plus five extra places to stand. The African Union will vote on who gets to sit and stand there.

- The Arab Group also wants its own seat in the bus.

- And then there’s the Uniting for Consensus Group. These are jealous rivals of the G4, such as Italy, Argentina, and Pakistan. They know they’ll never be allowed to sit down, so they want everyone else to have to stand, too. They’re trying to ensure that no solution will be found.

Meanwhile, the P5 are sitting comfortably, and none of this bothers them in the least. They let the line of cars behind the bus bicker among themselves. Divide and conquer. They do the same thing with the countries standing on the bus, too, the non-permanent members. From their seats, the P5 exert pressure to ensure these countries don’t get together to discuss the matter, so they’ll never be able to reach a common stance regarding the P5.

Every so often, the P5 makes a gesture of goodwill toward the caravan behind the bus. For example, France has voiced support for the ACT Group’s poster. And the United Kingdom says it’s fine for some African countries to take a seat, as long as they don’t touch any buttons. But the P5 are utterly ignoring the “Would you like to sit down? I’d be happy to stand” stickers on the wall of the bus, that urge those with seats to be courteous to fellow riders. None of them are willing to stand up so that another country can sit down.

The Berlin Wall of our time

Like we said, the situation is enough to make you throw up your hands in despair. Because let’s be honest. If you were in charge of the bus, who would you let get on, and who would you turn away? And under what conditions? How can the entire world ever agree on those? And what guarantee do we have that the balance of power won’t rapidly shift yet again?

Besides, even if all the cars behind the bus agreed, you’ve still got those stop buttons. A veto can block every attempt at veto reform.

But – as we already wrote – what if we think of the veto as a kind of Berlin Wall? What if we make peace with the fact that we can’t see the solution now, but it will inevitably come? Suddenly there’s a lot less cause for despair.

Illustration by Aimée de Jongh

After all, the right of veto was invented as a way to keep the superpowers in the United Nations, a way for the P5 to secure their influence in the world. In that sense, the right of veto is similar to the Berlin Wall. It, too, was meant to protect the dominance of a superpower – the Soviet Union. Like the Wall, the right of veto is a way to maintain the status quo.

But history has taught us that the world does not submit to status quos.

There comes a moment when a status quo becomes untenable. A moment, perhaps, when other countries become as powerful as the P5 and it’s important to keep them in the United Nations. A moment, perhaps, when the cars behind the bus reach consensus on a better approach. A moment, perhaps, when the status quo simply becomes too ridiculous for words.

The Berlin Wall ultimately fell, even though just days before, that still seemed unthinkable. And so, too, will it go with the veto.

In any case, it will require a united crowd. It was a united crowd of Berliners who tore down the Wall. A united crowd killed every senator who failed to respect the people’s veto in the Roman Republic.

The question is: how high a price must we pay before such a crowd rises to its feet? How many more victims must die in Syria? What has to happen before the cars behind the bus force it off the road? What has to happen before the Wall falls?

Research Assistant Lisa Peters contributed to this article (original Dutch version published in December 2015). English translation by Grayson Morris and Erica Moore.

More from De Correspondent:

What’s deadly dull and can save the world? (Hint: We can’t stand it)

What do poor people need most? Food? Healthcare? Education? The answer is as surprising as it is simple. And it can be found under fluorescent lights and modular ceilings.

What’s deadly dull and can save the world? (Hint: We can’t stand it)

What do poor people need most? Food? Healthcare? Education? The answer is as surprising as it is simple. And it can be found under fluorescent lights and modular ceilings.

A day in the life of a sniper fighting ISIS

In few places has the fighting against the Islamic State been as heavy and sustained as in the Syrian town of Kobani, near the Turkish border. Filmmaker Reber Dosky made the trek to Kobani and came back with a unique portrait of a sniper in a battered city.

A day in the life of a sniper fighting ISIS

In few places has the fighting against the Islamic State been as heavy and sustained as in the Syrian town of Kobani, near the Turkish border. Filmmaker Reber Dosky made the trek to Kobani and came back with a unique portrait of a sniper in a battered city.

Big business orders its pro-TTIP arguments from these think tanks

Think tanks present themselves as independent providers of arguments, facts, and figures in the ideologically charged debate on TTIP, the pending free trade agreement between the U.S. and the EU. But is that really the case? Together with the Platform for Authentic Journalism and fellow correspondent Dimitri Tokmetzis, Tomas Vanheste investigated where think tanks get their money and whether this influences their work.

Big business orders its pro-TTIP arguments from these think tanks

Think tanks present themselves as independent providers of arguments, facts, and figures in the ideologically charged debate on TTIP, the pending free trade agreement between the U.S. and the EU. But is that really the case? Together with the Platform for Authentic Journalism and fellow correspondent Dimitri Tokmetzis, Tomas Vanheste investigated where think tanks get their money and whether this influences their work.