In my introduction to this series, I admitted to my political illiteracy. You might be suffering from this malaise too, I suggested, which is why democracy is in trouble at this time of political crises around the world. I said I was off on a journey of discovery and invited you to join me.

First stop: arriving at some sort of shared understanding about what “democracy” means. It turns out that in practice, when including the elements of power and who has it, the word is more complex than plain government by the people – and few places can claim to be leading by example. At the end of that leg, I was left wondering: can we fix democracy?

Well, here’s some good news: some people are certainly trying.

Read this story in one minute.

In 2005, academic Graham Smith put together a 133-page report showcasing global examples – 57 in total. Collectively, they revealed ways to deepen citizen participation in political decision-making, including ones you’ll never have heard of just by watching events in the global north – the participatory budgets invented by the Brazilian city Porto Alegre, for example (more on those later).

“One of the really exciting things that happened to me when I did that work was realising how much there was for us to learn, us as in the minority world, from practices elsewhere,” says Smith. “That was really important for facing down the sort of arrogance that can happen: we know what’s best for democracy, we are the cradle of democracy.”

What follows, then, is an updated taste of those innovations – using Smith’s research as a starting point – varied for geography, approach and scale of government. It’s inevitably partial, my choices a subjective reflection of one person’s view, optimistic or otherwise.

‘Any attempt to define what democracy might mean will be missing something’ – Giovanni Allegretti

And a word of caution, from Giovanni Allegretti, an architect and researcher who for years has wrestled with ideas of what “democracy” might mean and different versions of its practice: “There’s always a missing part, in every example that you can choose.”

That’s because political alternatives, at whatever level they emerge, take place within existing economic and financial systems. “When you do a lecture on democracy and you want to show alternatives, what we must do in the end is always cherry picking. They show another direction but they are never able to be complete.”

Allegretti recommends complementing searches for democratic alternatives with learning at the same time about emerging alternatives to gross domestic product. One place to start: the concept of “degrowth economies” described here by Jason Hickel for The Correspondent.

With that disclaimer, prepare for a global tour of innovations intended to bring more of the power to more of the people.

1. Participatory budgets

Born in Porto Alegre, Brazil in 1989 and adopted by more than 11,000 places in 71 countries.

Here’s the idea: participatory budgets require local engagement in deciding how a city should spend money, both in creating a city-wide budget and monitoring. This combines open assemblies with representative bodies.

Early versions were particularly effective at engaging marginalised segments of the population – in particular, women and people on lower incomes. A well-functioning participatory budget (PB) becomes an embedded part of the annual budget cycle. Citizens review the previous year’s spending, decide priorities for the current year, and make projections for future spending all based on locally determined needs.

Porto Alegre’s original process featured three distinct levels of citizen engagement: popular assemblies at regional and neighbourhood levels; regional budget forums; and the municipal budget council itself. The idea has since rippled out to every continent except Antarctica, including to Marsabit County in northern Kenya, bordering Ethiopia.

One man with more than a passing interest is Christopher Ogom, who studied its effects on his home of Marsabit as part of a US master’s programme. The 33-year-old knows first-hand the problems of gender discrimination, poor accountability and failure to identify community needs which characterised previous budgets. Decisions on spending in Marsabit were once exclusively male and opaque affairs, biased in favour of local leaders’ pet projects which did little to ease hardships faced by the pastoral population.

PB explicitly draws in local women, youths and people with disabilities to challenge traditional gender roles and other embedded hierarchies. A series of meetings – from local communities through several layers to sub-county and county levels – pools funding priorities for local agreement prior to them being sent to the national treasury.

“Top priority will be water, health, you know these issues – they’ll want a borehole to be built here, a hospital to be constructed there, a piping system there,” Ogom explains. “This is a marvellous way of government. If you go to Marsabit right now, you really see a lot of development coming up because people are placing the resources where they’re needed.

“As this process becomes transparent, communities will get to understand how much is allocated for them – which is something that has previously been hidden, they have never known this kind of information. This transparency should be further strengthened. People are feeling that sense of taking responsibility by themselves.”

Marsabit is one of several county-level PBs adopted in Kenya, an innovation brought forward in the wake of constitutional reforms in 2010.

PBs are now embedded in the global political landscape, with nearly two in every five found in Europe, including eastern and southern countries. Among the standouts are Portugal, which has held three national PBs, Ukraine, Poland and Spain. Europe moved ahead as changing political winds in Brazil killed off many of its PB processes. That left South America with a quarter of the worldwide total, just ahead of Asia’s share. Africa hosts about 8% of them.

2. Citizens’ Initiative Review

A direct democracy technique born in the United States and now adopted in Switzerland and Finland.

Smith is a long-time fan of Ned Crosby, the octogenarian US political scientist and philanthropist who in 1971 invented the process for Citizens’ Juries. Think criminal juries but for political issues. Crosby wanted to encourage quality thinking by a small group of citizens on a chosen public policy issue, or to evaluate political candidates. His design gathers representative microcosms of the voting population, helps them to learn about an issue, and then to brainstorm solutions.

The Citizens’ Initiative Review (CIR) was one concrete result. The first, held in the northwestern US state of Oregon in 2008, concluded with 23 registered Oregon voters reaching a considered view on Ballot Measure 58, a ban on bilingual education which proposed limits to foreign-language teaching in state schools.

CIRs mostly recruit panelists who are trained in dialogue and deliberation techniques, before hearing from advocates on both sides of an issue. They can turn to independent experts for help, and rely on voting or consensus-building techniques to reach conclusions. Panels typically summarise their reasoning for or against any measure – that first Oregon CIR split nine people in favour and 14 against. Their statement is made available to all voters in any constituency to help citizens reflect more deeply on a topic before casting a ballot.

In Oregon, CIRs are now part of official process in state elections, although struggles persist to secure consistent funding. In 2008, Ballot Measure 58 fell flat as Oregon voters chose the same line as the CIR majority. The technique survived and has spread since, notably to Switzerland where a centuries-old tradition of direct democracy exists in citizen-initiated votes.

In common with every place that holds elections or referendums, Swiss voters suffer time pressures and information overload. CIRs can ease those problems while countering establishment bias on topics which politicians often have failed to tackle. “When people launch an initiative, it is very often because the politicians haven’t been able to respond to an issue, to give an acceptable answer,” says Charly Pache, a political science researcher at Geneva University.

Switzerland’s first CIR was held in 2019 in Sion, a commune in the southwestern Valais canton. Twenty panelists examined a proposal to double the minimum amount of social housing provided nationally to 10%. Their report in January 2020 shared arguments for and against, prior to a national vote in February which rejected the idea.

CIRs need funding and, ideally, institutional buy-in. In Oregon, for example, no further citizens’ juries have been held since 2016 due to a lack of state funding. That lack of money is telling. While CIRs can make issues clearer to voters, they do little to reduce the conflict inherent in campaigning and elections – and still less to tilt the balance of power. For reformists seeking game-changing democratic innovations, they’re hardly electrifying.

3. Representative population samples

A mechanism designed to deliberate issues and recommend policy responses, also known variously as “mini publics” or citizens’ panels.

Representative population samples are similar in design to citizens’ juries, but mini publics typically tackle more complex issues, often at larger scale – national government, or even global issues – with outcomes that can be more impactful than advisory statements for voters.

While Brazil has cut back citizens’ involvement in participatory budgeting, another democratic innovation has made its debut in South America’s most populous country – the Conselho Cidadão or citizens’ council.

The objective? To tackle solid waste management in the tropical northeastern coastal city of Fortaleza. A citizens’ collective, Delibera Brasil, coordinated various groups in the city prefecture to create a citizens’ council tasked to examine the city’s R$200m (US$37m) annual spend on garbage. This topic might not grab headlines, but the method has already produced some stand-out results around the world.

In Ireland, a de facto ban on abortion was lifted in 2019 after debate within a citizens’ assembly helped to break the deadlock among politicians. That initiative opened the way for a national referendum in which citizens voted two to one to drop the ban.

In Australia, a similar approach killed off the South Australian government’s proposal to expand a long-term storage facility for nuclear waste.

In South Korea, another citizens’ panel revived a stalled nuclear power project.

Common to all these examples was the role of representative panels of citizens who acted as a catalyst for policy changes by delivering deliberated views on the questions at hand.

If this is a revolution, Fortaleza is a small and quiet one – involving quotas for gender, age, occupation, income and education

The format for these panels includes all the elements advocated by Democracy R&D, a network whose members specialise in citizens’ council-style events, from local to global. Participants are chosen by lottery selection, or similar, to ensure a diversity of views. Groups are granted the necessary time, information and opportunities to talk through their differences. Facilitators help them to weigh trade-offs in reaching well-grounded policy suggestions.

According to a forthcoming study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, more than 700 such deliberative groups have been gathered over the past several decades. Their popularity is surging – and includes a significant number tasked with responding to the climate crisis. Since late 2018, these have been prompted in part by direct action campaigns and calls for citizens’ assemblies from Extinction Rebellion.

In 2019, Ostbelgien – the German-speaking part of Belgium – went a step further by voting to create a permanent second parliamentary chamber of members chosen by lottery.

Back in Fortaleza, 40 participants in Delibera Brasil met five times between October and December 2019. During the first three sessions, they learned about waste challenges in the city of 2.6 million people. For the remainder, they deliberated on how to handle them. Participants who made it to at least four meetings were paid R$500 (US$92) each for their time, transport costs and other expenses.

If this is a revolution, it’s a small and quiet one – involving residents selected according to quotas for gender, age, occupation, income and education, then tasked with talking about the problems of rubbish dumped outside official collection processes and treatment facilities. Despite support from the city mayor, the prefecture and other stakeholders, there’s no guarantee of any concrete outcomes from the work.

Putting recommendations into practice depends on office holders taking action before their mandate expires in 2020. The coronavirus pandemic, which has ravaged Brazil, is not helping. “When we looked at their plan of implementation we could see that it was going to take longer than we thought. Now, with coronavirus, we really don’t know,” says Delibera Brasil co-founder Silvia Cervellini.

4. vTaiwan, crowdsourced democracy

An evolving experiment in crowdsourced democracy, which aims to engage the entire society in open consultation on policy issues.

While Covid-19 has devastated many communities around the world, and exposed serial incompetence in governments such as the UK’s, it’s also thrown up remarkable stories of political skill, foresight and ingenuity. None is more remarkable than Taiwan.

The island of nearly 24 million people, just 81 miles (130km) off the coast of mainland China, might have been expected to be hard hit by the coronavirus. Yet by the end of May, it had registered 442 confirmed cases – 351 of them imported, 55 local ones and 36 among naval crew members. Total number of deaths? Seven.

Part of the reason might be its female president, Tsai Ing-wen. Current data shows that countries with women in leadership positions have six times fewer confirmed Covid-19 deaths than those led by men. (Perhaps that’s the democratic innovation we need – more women in power). Correlation is not causation, of course, though it definitely begs closer scrutiny.

President Tsai drew on Taiwan’s prior experience of the Sars pandemic to introduce targeted measures and medical checks, immediately – from December last year. That massively cut the risk of an outbreak and made lockdown unnecessary. She also called on the services of both vTaiwan – an online-offline public consultation phenomenon – and the remarkable Audrey Tang, an activist citizen hacker-turned-Digital Minister.

“This is a great moment, and we could not have done the counter-coronavirus efforts so well without the previously civic tech, now also civil engineers,” says Tang, referring to thousands of volunteer coders, activists and ordinary citizens who donated their expertise to quell the virus. “It’s a very short iteration cycle that brings people’s innovation, amplifying it, into national visibility within a matter of days. That’s the turnaround cycle.”

If you do not trust the citizens, there’s no way the citizens will trust back. You trust citizens by empowering them with real-time open data – Audrey Tang

Taiwan’s innovations include a real-time national map of pharmacies with stocks of face masks. Anyone seeking to collect their allocated masks can check a pharmacy’s stock levels before and after; withdrawals are typically logged within minutes. This transparency calms panic buying and helps to curb rumours. Useful tips, such as using rice cookers to disinfect and refresh face masks, are shared quickly and widely.

Taiwan’s digital participation platform didn’t emerge out of nowhere; it was there before coronavirus. The same technologies and approach had contributed to startling victories in forcing Uber and Airbnb to compromise their predatory business models on the island. In both cases, public pressure was expressed and moderated via the civil society platform, ahead of direct talks with government. Tang talks of creating utopias for public action.

vTaiwan itself is a product of protest, including Tang’s. Today’s Digital Minister was, not long ago, among demonstrators occupying government buildings as part of the Sunflower Movement in 2014. Protest erupted in response to the then government’s attempt to forge a trade deal with China, which was subsequently defeated. vTaiwan has been described as a new cyber-punk frontier of democracy, a story which deserves several books.

Tang doesn’t exactly buy the idea of democratic crisis. She prefers a computing term for data transmission speeds – the bit rate – to make her argument: “I see that with the social media and the hashtags an entirely different way of organising collective action has happened. Public service can remain in the old bit rate, which is voting like four bits every four years.”

The higher bit rate enables government responses along the lines already seen with Covid-19 in Taiwan, a litmus test of what’s possible with what Tang calls collective data democracy or data governance.

Three possible outcomes follow from this heightened transparency: to make the state transparent to citizens, as Taiwan has on this issue; to make citizens transparent to the state; or to serve the agenda of multinational capitalist entities.

“If you’re a government official, you need to trust the citizens. If you do not trust the citizens, there’s no way the citizens will trust back. You trust citizens by empowering them with real-time open data.”

5. Non-state efforts to secure democratic freedoms for the disempowered

Rights-based claims for autonomous systems where rights are not protected in law, from Syrian Kurds and Mexican zapatistas.

The crowdsourced democratic innovations in Taiwan are more remarkable given the island’s precarious legal status but maybe that precariousness is the catalyst for profound democratic innovations which benefit groups typically left out under other systems. What of people without power in places that have nothing like nation-state rights or any sort of recognition?

Consider Rojava, or Syrian Kurdistan. The enclave’s autonomous government has put women into positions of power, in single-sex army units and in political office, against a backdrop of military aggression from both Turkey, to the North, and Syrian authorities in Damascus.

Since 2012, both Kurds and Arabs have moved more towards democratic communalism, an idea that aspires to smaller-scale, locally directed government in place of centralised rule.

In Chiapas, southeast Mexico, indigenous zapatistas run their lives autonomously in the face of low-intensity warfare against them by the Mexican government. They’ve held out for more than 25 years, since their masked and poorly armed fighters occupied streets in several Chiapas cities and towns on 1 January 1994.

Autonomous communes, councils of good government, regional assemblies and collectively owned land have enabled zapatistas to attempt to remedy centuries of poverty, inequality, racism, and exploitation. Their example, incorporating everyday people into all aspects of day-to-day government, is on an entirely different and more advanced level from Porto Alegre’s participatory budgeting.

Clearly, then, vigorous examples of democratic innovation can be found around the world – it’s not our human ingenuity that’s lacking. Learning about these innovations is a hopeful exercise, a salve to the stories of toxic politics in conventional systems. The key question is how to adopt such innovations more widely and at scale. How do we manage such transformational changes, upending top-down government in the process?

What can we learn from history?

Knowledge alone is not enough. Smith is excited about progress but also wistful as he reflects on events since his 2005 report: “Fifteen years ago, I was naive about the extent to which these things would be taken up, to the extent that they would become a familiar part of our politics.”

“There have been a whole series of what I would call relatively small wins when I was expecting larger victories. I still despair about the structural barriers to getting these things in place, the lack of desire and the lack of willing,” he says, referring to the political structures of the status quo.

“We know how to engage well, we know how to empower but the question is whether those with power are willing to see this stuff flourish. That’s where the block is,” says Smith, who now combines his professorial career with climate activism.

So our tour of democracy innovations ends where it began: wrangling with questions of power, the too narrow slice of humanity which holds it, and how to loosen their grip for our collective benefit, the current power holders’ included. It’s gripping stuff. There are stirring stories from history to describe how societal change comes about.

Freedoms seem always to demand some form of struggle. Struggle directed outwards against incumbent power – certainly; but also inwards, directed at personal ignorance, egotism and prejudice. What sort of people have successfully managed that balance in the past? What was it that they did, and how did they manage?

Would-be democracy innovators, including us political illiterates, have much to learn from our predecessors in history, the widely known and less familiar.

So stay tuned, fellow sufferers. We’re off to seek some of them out.

Editor’s correction: a previous version of this article stated that representative population samples initiated in Brazil. That country was in fact just the latest to have used it.

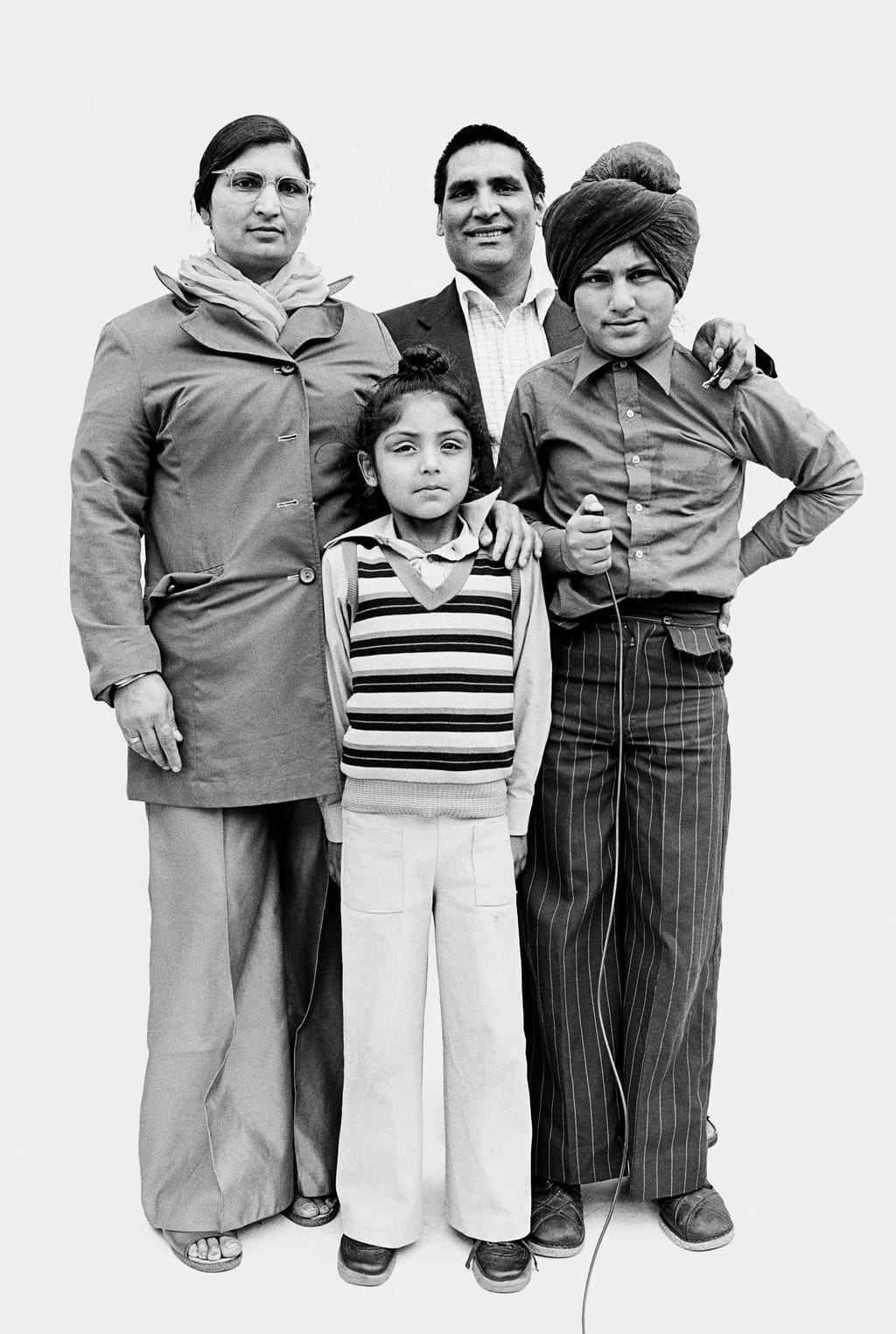

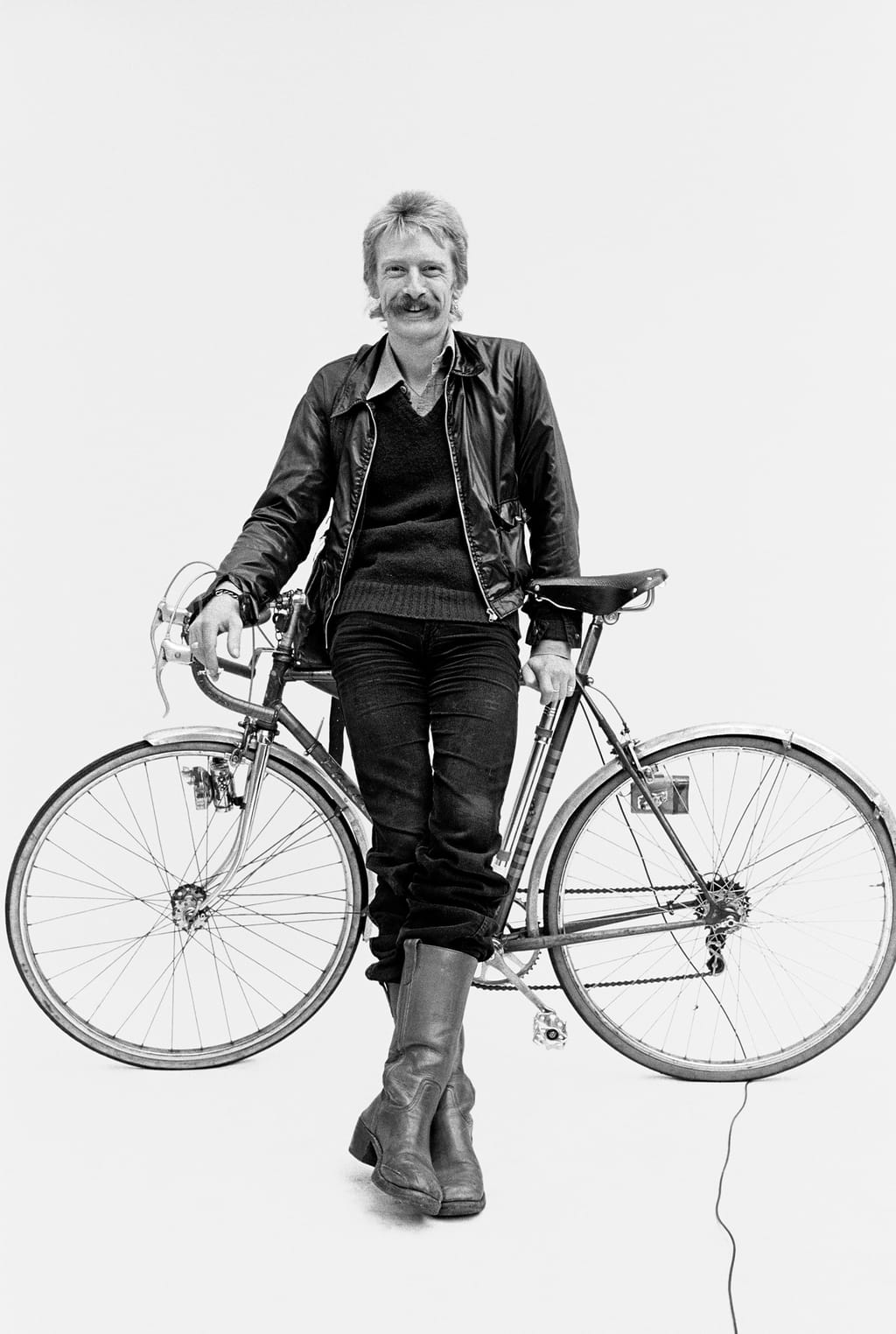

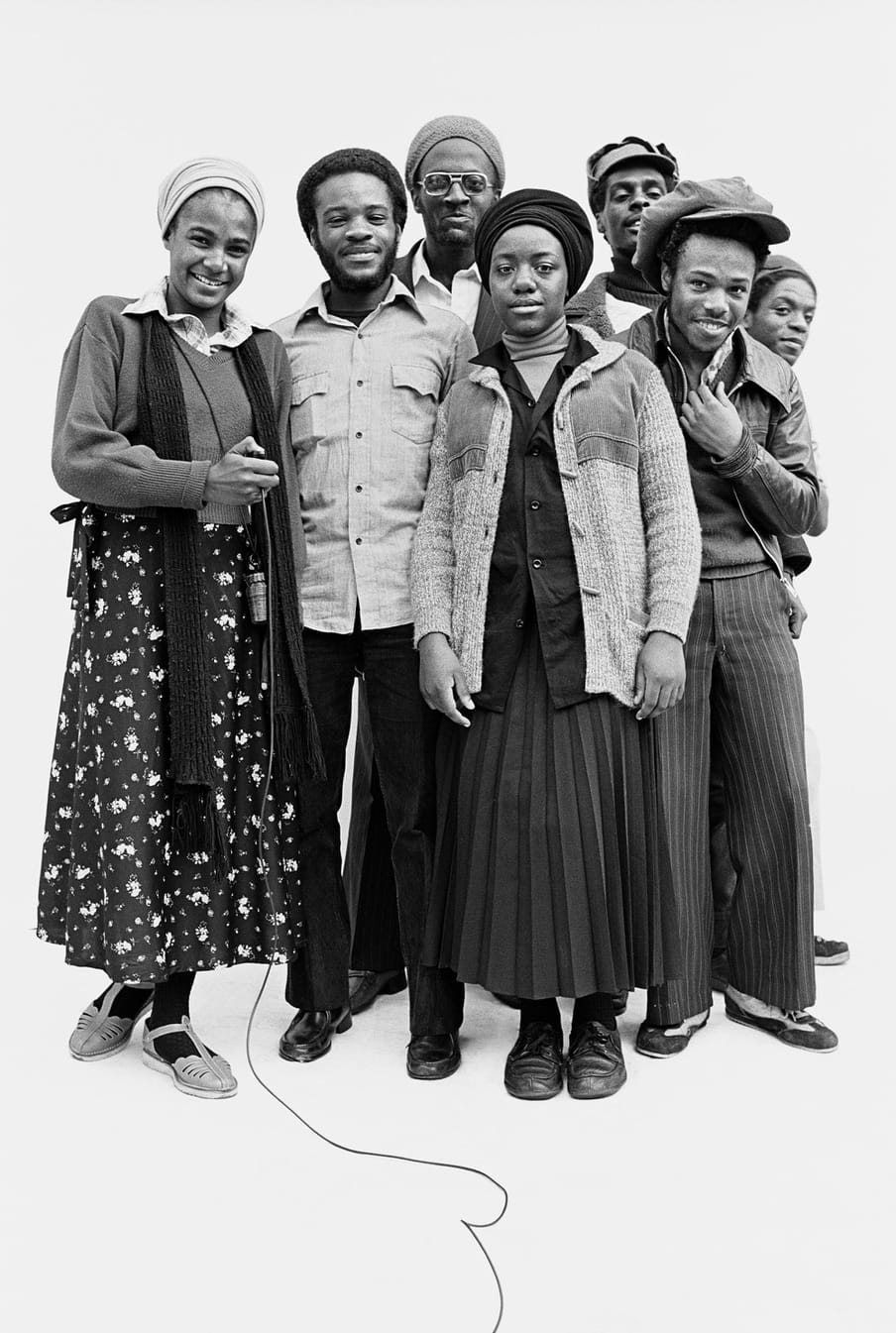

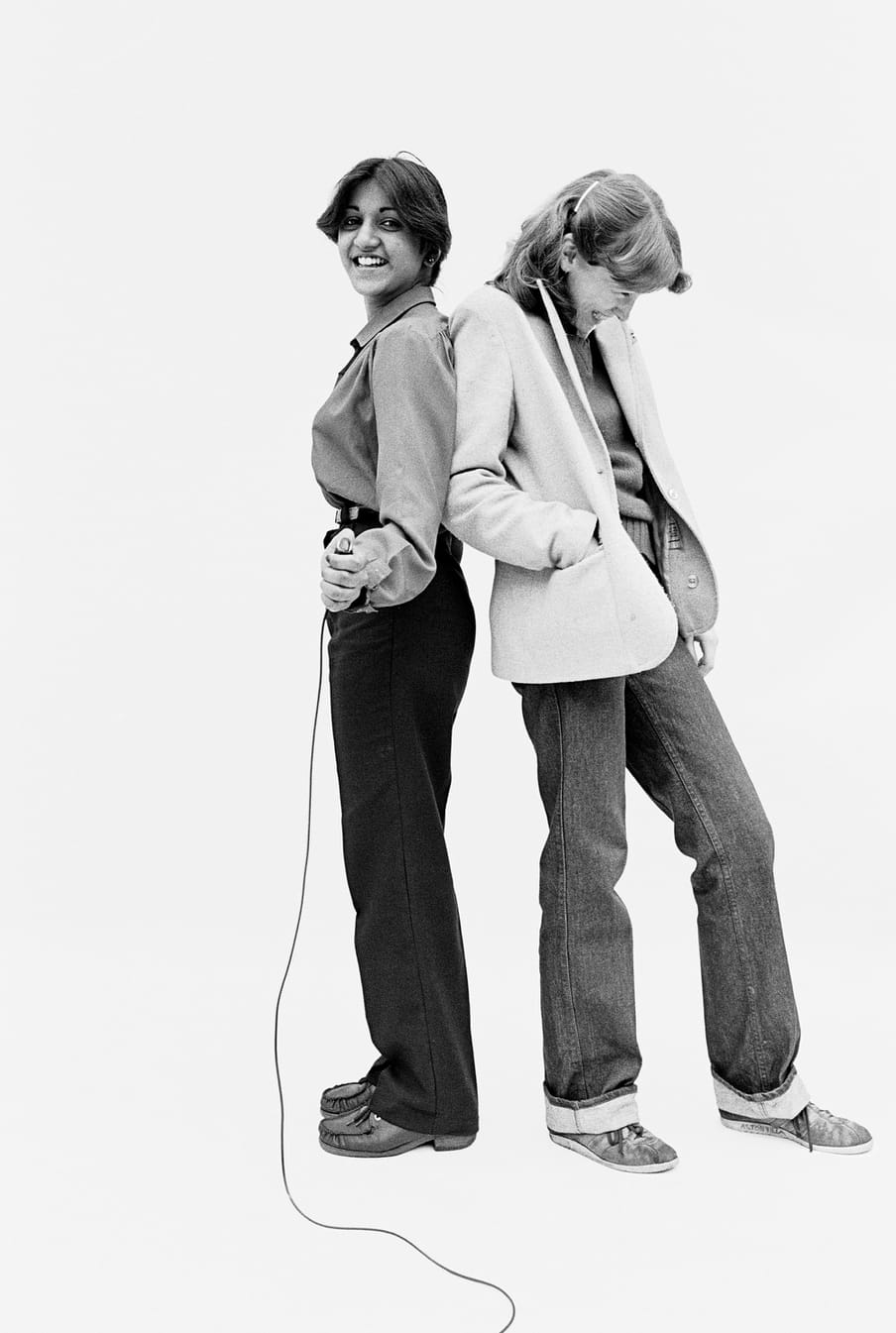

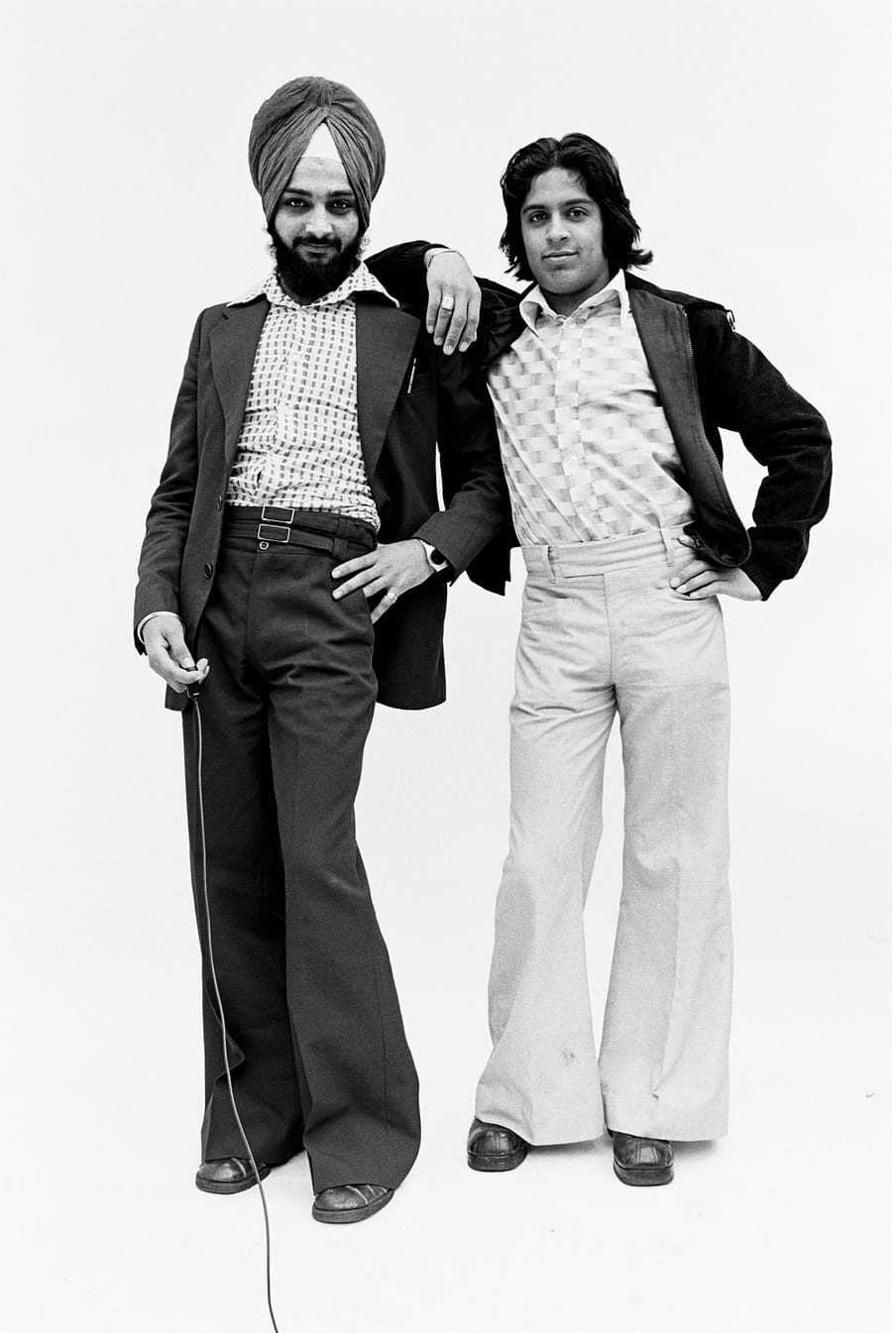

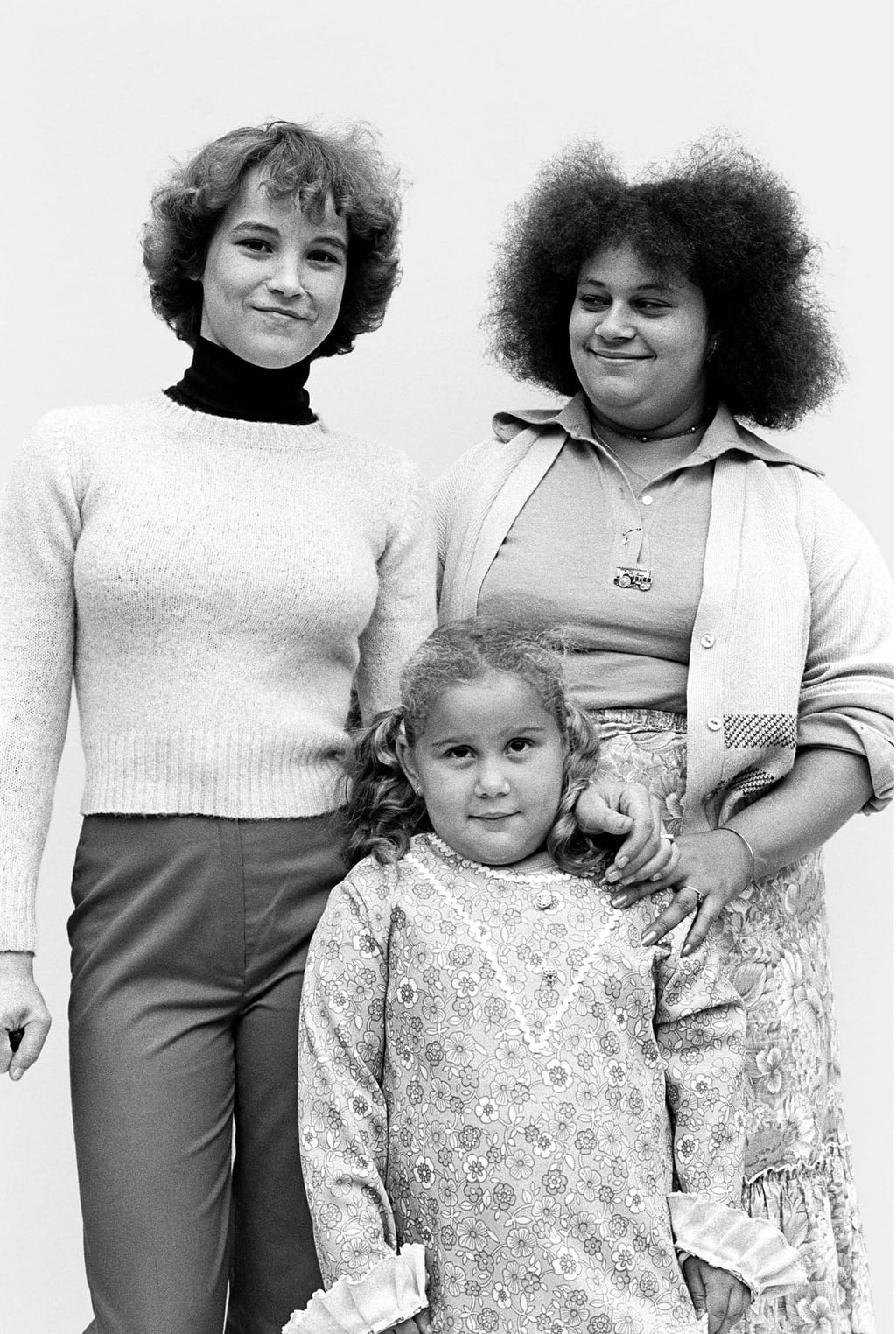

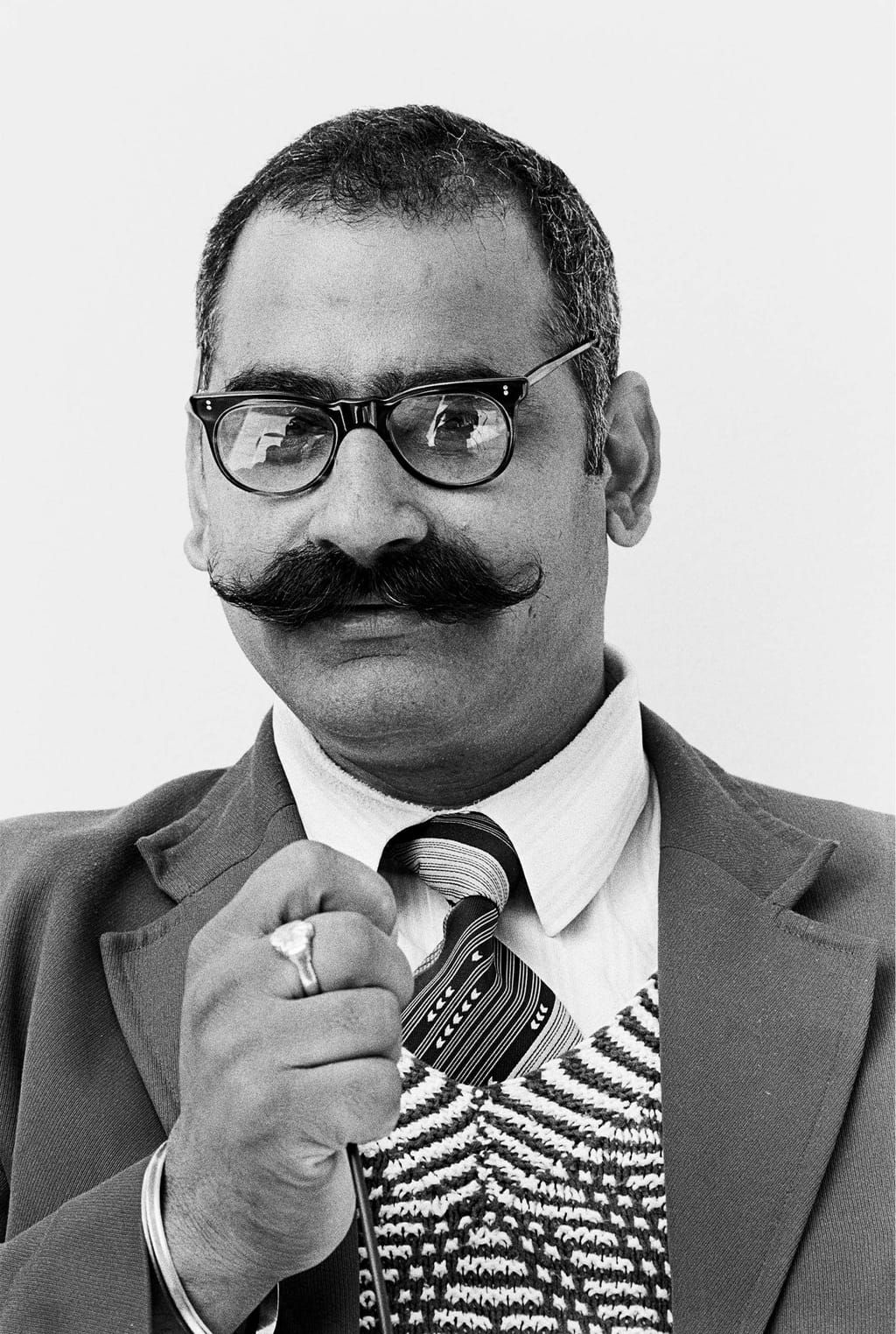

About the images

In 1979, Derek Bishton, Brian Homer and John Reardon created a pop up photography studio on the street outside their office in the multicultural district of Handsworth, Birmingham. Their neighbourhood was often portrayed in negative ways by mainstream media, so they decided to challenge this representation.

About the images

In 1979, Derek Bishton, Brian Homer and John Reardon created a pop up photography studio on the street outside their office in the multicultural district of Handsworth, Birmingham. Their neighbourhood was often portrayed in negative ways by mainstream media, so they decided to challenge this representation. They launched a participatory project, inviting their neighbours to literally and figuratively put themselves in the frame and take their own images. More than 4,000 people stopped by to take part in this groundbreaking ‘Selfie’ project, which generated a unique archive of images of the moment the UK emerged as a multicultural society. (Veronica Daltri, Image editor).

Dig deeper

My name is Patrick and I’m politically illiterate. You are too

Talking politics often feels like a personal health hazard. Unless we can learn to understand our own roles in a dysfunctional system, there’s no chance of fixing it. Come learn with me.

My name is Patrick and I’m politically illiterate. You are too

Talking politics often feels like a personal health hazard. Unless we can learn to understand our own roles in a dysfunctional system, there’s no chance of fixing it. Come learn with me.

The real story of US democracy isn’t the drama. It’s the complete unresponsiveness to it

Democracy in the United States has often been declared at risk – if not actually dead, then at least on life support. But American democracy isn’t dead, it’s in a deep and worrying coma.

The real story of US democracy isn’t the drama. It’s the complete unresponsiveness to it

Democracy in the United States has often been declared at risk – if not actually dead, then at least on life support. But American democracy isn’t dead, it’s in a deep and worrying coma.