Office of the International Federation for Human Rights, Paris, France

The odd assembly of people agreed on one thing: something must be done. And quickly.

Charles Heller had sent out the last-minute invitation only two weeks before. Despite the short notice, some 15 Italian lawyers, German sailors, French aid workers and British academics were sitting in this grey office building, in a Parisian alley in the city’s 11th Arrondissement, on a Friday in September 2017.

Everyone in the conference room knew the problem they were facing was getting out of control. It was becoming increasingly difficult to rescue migrants in distress in the Mediterranean because the Libyan coastguard was more active and aggressive in international waters.

The Libyans aren’t in it for fun, but for money. The Libyan coastguard is financed, equipped and coordinated by Italy and the EU. To save migrants from drowning, or at least that’s the official story. And, oh right, as a nice bonus: fewer migrants make it to Europe. Because the Libyans take the migrants back to their own coast and put them in detention centres.

It was making the people in this room furious, Charles Heller, a researcher, most of all. He believes the violence that these migrants suffer in Libya while they are entitled to a fair asylum procedure according to international treaties is the greatest injustice of our time. Hence the topic of the meeting: strategic litigation. To start a court case, hoping it will result in jurisprudence that forces countries to change their policies. If European politicians continue to turn a deaf ear to this injustice, then perhaps the courts will listen.

Heller’s work had served as the foundation for such strategic cases before. He heads Forensic Oceanography, a research project at the University of London, which reconstructs human rights violations at sea. Consider him an activist investigative journalist.

Under international and European law, a migrant cannot be sent back to a country like Libya, where his life or freedom will be at risk. The question that currently keeps Heller up at night is: how can you hold Europe legally responsible for the actions of the Libyan Coast Guard? Or, as he phrases it in his characteristic tone – contemplative yet confident – to the group in Paris: “How do you translate violence into violations?”

The lawyers in the room obviously have ideas about this, the academics cite previous research, the sailors contribute anecdotes about their rescues. But as the meeting draws to a close, no tangible follow-up steps are on the table. Except: keep your ears and eyes open.

All they can do is wait for that one perfect case.

On the shores of Tripoli, Libya

23-year-old Patrick was not afraid when he boarded the balloon from the Libyan beach at 11pm that night. A balloon: that’s what the inflatable boat felt like. He wasn’t really any good at swimming, but it was dark, so he couldn’t see the gigantic body of water ahead of him. And anyway, his older brother had made the crossing four years ago, and was now working in a pastry shop in Turin.

It was uncomfortable, though – at least 130 people had been packed into the little boat. He could hardly see his wife and two-year-old daughter because so many people were sitting between him and the pointed front end of the boat, where the women and children had been ordered to board first.

Around midnight, the engine roared and they were off, bashing their way through the surf along the Libyan coast. Onwards to Italy – onwards to a better future.

They bounced across the water for hours. The wind grew stronger. The waves grew higher. Women started praying out loud. Somebody let out a scream. Patrick called out to his wife: wouldn’t it be better for her to pass the baby to the back, to the men?

Their young child was handed back through the passengers – but where Patrick was sitting, he had nowhere to put her down. The man in front of him offered to hold her; unafraid of the waves, he turned the movement into a game for the little girl. She squealed with laughter.

Suddenly: silence. Patrick looked around. The engine had stopped running; they were out of petrol. The boat was now tossed from side to side by the waves, drifting aimlessly.

With the Thuraya satellite phone they received from the Libyan smugglers, they tried to call the Italian coast guard. SOS. SOS.

Just after dawn, Patrick spotted a little white plane. He took off his T-shirt, waving it over his head. Come back! The plane circled a few times and tossed an emergency flare into the water, raising a plume of smoke not far from their little boat. Help was on the way, Patrick knew.

But before he could enjoy his relief, he heard a loud bang. Pgooo. Followed by a giant stream of bubbles from the side of the boat. The hole was the size of a fist, and not far from Patrick. Water started gushing on board. Using a can, he reached down towards his feet, trying to bail it out. It was no use.

“Stay calm, everyone,” Patrick cried. But panic was already taking hold. People were trying to stand up, falling overboard.

Patrick clung desperately to the deflating rubber. He lost any sense of direction. Left, right, up, down: water everywhere, flailing limbs everywhere. And then, somewhere on a horizon: a ship. No, two!

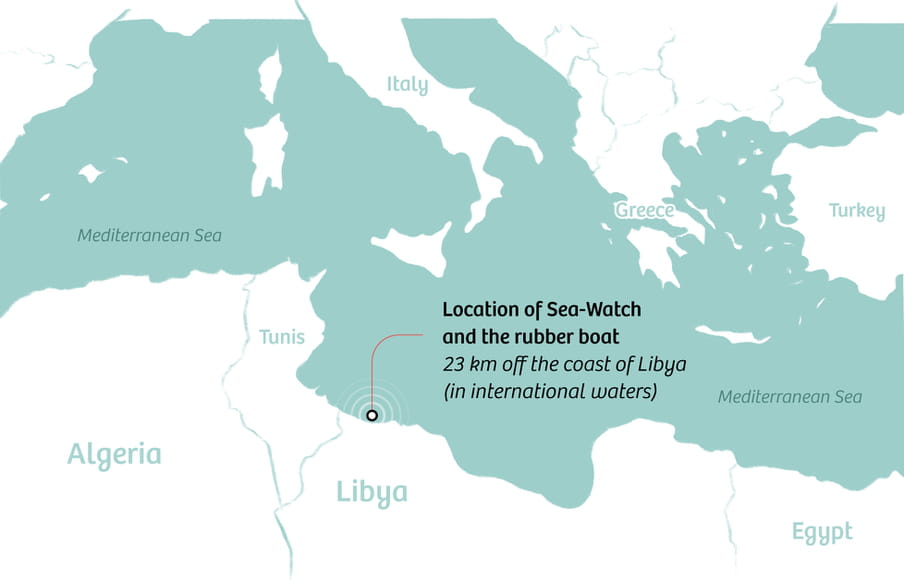

Aboard rescue ship Sea-Watch 3, some 23km off the Libyan coast

Julian Köberer (32) was startled awake by the pounding on his cabin door. “We’ve got a boat!” The first officer of the Sea-Watch 3 checked his watch. 8am. He had been sleeping for four hours.

Into his clothes, up to the bridge.

On his previous rescue missions, someone had shouted through a megaphone almost every night when a new boat was spotted. But these days, far fewer migrants attempted the crossing. This was the first rubber boat needing a rescue since the Sea-Watch 3 had left Valletta three days ago.

The Maritime Rescue Coordination Center (MRCC) in Italy, the headquarters of the Italian coast guard in Rome, had sent them the exact coordinates of an SOS signal at 06:00 that morning. Two hours had passed since then: the current made it harder to search.

And they were not alone – that much was clear to Julian as soon as he peered through the binoculars on the bridge.

- A French military ship to starboard radioed in that it was willing to offer help if their assistance was needed.

- A Portuguese reconnaissance plane was circling in the air and had just dropped a couple of emergency flares near the rubber boat.

- And a fast ship overtook the Sea-Watch to starboard, heading for the smoke: the Libyan coastguard.

Hurriedly, Julian discussed the situation with Pia and Joe, the captain and the head of the mission, while their own, slower ship also sailed towards the plumes of smoke.

At 9:04, the voice of the Libyan coastguard echoed across the bridge radio. Crackling, and with a strong Arabic accent. “Sea-Watch, this is the Libyan coastguard. We are now responsible for this rescue. Over.”

Joe grabbed the receiver right away. “Negative. We have orders from MRCC. We will continue rescue. Over.”

It was quiet for a moment, and then the same Arabic accent was heard again. “Thank you thank you. Over.”

Julian and his colleagues started laughing. “Did they just say, OK, thanks?”

But their laughter stopped shortly after, when Julian spotted people lying in the water from his vantage point on the bridge. The Libyan coastguard had sailed towards the sinking boat – and completely ignored these people who had fallen overboard.

Sea-Watch immediately launched two speedboats to fish the drowning people out of the sea.

Meanwhile – contrary to every rescue protocol – the Libyan coastguard had pulled up right next to the rubber boat, causing a large wave to capsize the half-deflated plastic shell even more. By that point, Julian could see exactly what was happening: his Sea-Watch 3 had approached the Libyan coastguard and was just a few dozen metres away.

It was the first time Julian had seen someone drown. A floundering hand disappearing under the water, agonisingly slowly.

It was the first time Julian had seen someone drown. A floundering hand disappearing under the water, agonisingly slowly

He leaped into action. Sea-Watch had rescue devices aboard known as Centifloats: gigantic inflatable cylinders with ropes attached. A hundred people could hold on to it at the same time to keep from drowning. Julian ran to the aft deck and lowered the deflated orange tubes into the water, ready to launch.

But then doubt crept in. If he threw the inflatable tubes into the sea here, the people on the sinking rubber boat would have to swim another 20 metres to reach the Centifloat. Would they survive that? And what if the people who had been pulled onto the Libyan ship suddenly decided to jump, to get to the Centifloat? Wouldn’t even more people drown then?

He doesn’t release the Centifloat. Years later, he still often wonders if it was the right decision.

He was called to the deck: a child’s body had been brought on board. While the doctor was attempting to resuscitate, Julian took over her position on deck, helping people out of the speedboats and up the ladder.

As he pulled one hyperventilating person after another onto the deck and threw a blanket around their shoulders, the crew in the speedboats yelled to get his attention: the Libyan coastguard was throwing hard objects at their heads. Potatoes, apparently. Other rescue teams had been fired at by the Libyan coast guard in the past.

At 09:30, the Libyan coastguard called it a day. Julian saw the Libyans speed off, through a thick black cloud of exhaust. But he also saw there was still someone hanging overboard, clinging to a ladder. The boat accelerated; the man was almost invisible now, engulfed in the bow wave.

Julian heard Joe screaming into the radio on the bridge: “Libyan coastguard, this is Sea-Watch! You have one man in the water, you are towing him with speed. You are killing a person. You are killing a person. Over.”

He heard the sound of helicopter blades above him. It was like a war zone out there. The Italian coast guard helicopter also came in over the radio. “Libyan coastguard, stop your engines! We want you to stop! Now, now! You have one person on your side. Stop, please, stop!”

The Italians shouted “stop” 19 times. Then Julian saw the ship slowing down.

At that point, Julian had 58 people on board. And one small child, dead.

In the Tajoura detention centre, Tripoli, Libya

Patrick hadn’t slept for over 24 hours. But there was nowhere to sit, let alone lie down. They were packed together like animals. They hadn’t had any food yet, nothing to drink. He had rinsed the salt from his mouth with water from the toilet bowl in the corner. He was covered in scratches and bruises from fighting his way off the sinking boat.

His little daughter was dead. He was absolutely sure of it. In the wave caused by the Libyan coastguard vessel, he had seen the man holding her disappear overboard.

When he was pulled onto the deck of the Libyan ship, it was chaos – men and women were separated, the Libyans beating people with ropes. He had seen his wife there, at least, but he hadn’t been able to speak to her.

Jostled around the prison from place to place, Patrick wasn’t allowed to settle anywhere. Get lost, get out of here. A man tapped him on the shoulder: aren’t you also from Benin City? “Yes, yes I am! I had a clothes shop there,” Patrick said. The man gave him a place where he could curl up on his side against a wall.

Patrick did not cry. He felt bitter.

Someone patted him to wake him up; he had no idea how long he had been sleeping. A woman from the United Nations (UN) was visiting the prison. She asked if he wants to go back to Nigeria. Patrick didn’t have to think twice. Don’t worry, said the UN official. We’ll put you on a flight home before the end of the week.

Aboard rescue ship Sea-Watch 3, en route to Italy

The Sea-Watch 3 was still on the high seas when Julian typed a long email to the group he met in September in Paris. He had a thousand questions, jumbled and confused, but also a strong sense that they had experienced something important. He wrote: “It is possible that with all collected video material and also the voice recordings on the bridge there is a chance that this case might be interesting in regards of Europe’s and Italy’s complicity in the non-refoulement and the death of migrants at sea.”

Yes, everything had been recorded. The Sea-Watch 3 had recently been equipped with 10 cameras, while the crew’s helmets were mounted with GoPros. The idea was to give Sea-Watch ammunition against false accusations – such as the Libyan Navy was now posting on their Facebook page. They were accusing Sea-Watch of disrupting the rescue operation, and thus causing the deaths by drowning. In response, Julian and his colleagues immediately posted video material online showing how recklessly the Libyans had acted.

But Julian was starting to see that the material had even greater potential.

Julian instructed the crew to start conducting interviews with the migrants – some had seen family or friends climbing onto the Libyans’ boat. Making contact with those people will be difficult, but crucial, Julian emailed the group from Paris.

And: staying in touch with the migrants that Sea-Watch had managed to rescue would also be challenging. The ICT coordinator aboard Sea-Watch created a Facebook profile using the name "November 6 Incident". He handed out small notes with that name to the migrants: when you reach land, send us a friend request.

That afternoon, Julian used Signal to send a message to Charles Heller. “We might be able to have a case … ”

In the emergency shelter in Pozzallo, Italy

Other than a piece of paper with the name of a Facebook profile, 37-year-old Samuel had nothing with him when he entered the emergency shelter in Pozzallo, on the island of Sicily. He hadn’t asked anyone where they were taking him – all that mattered was that he was safe.

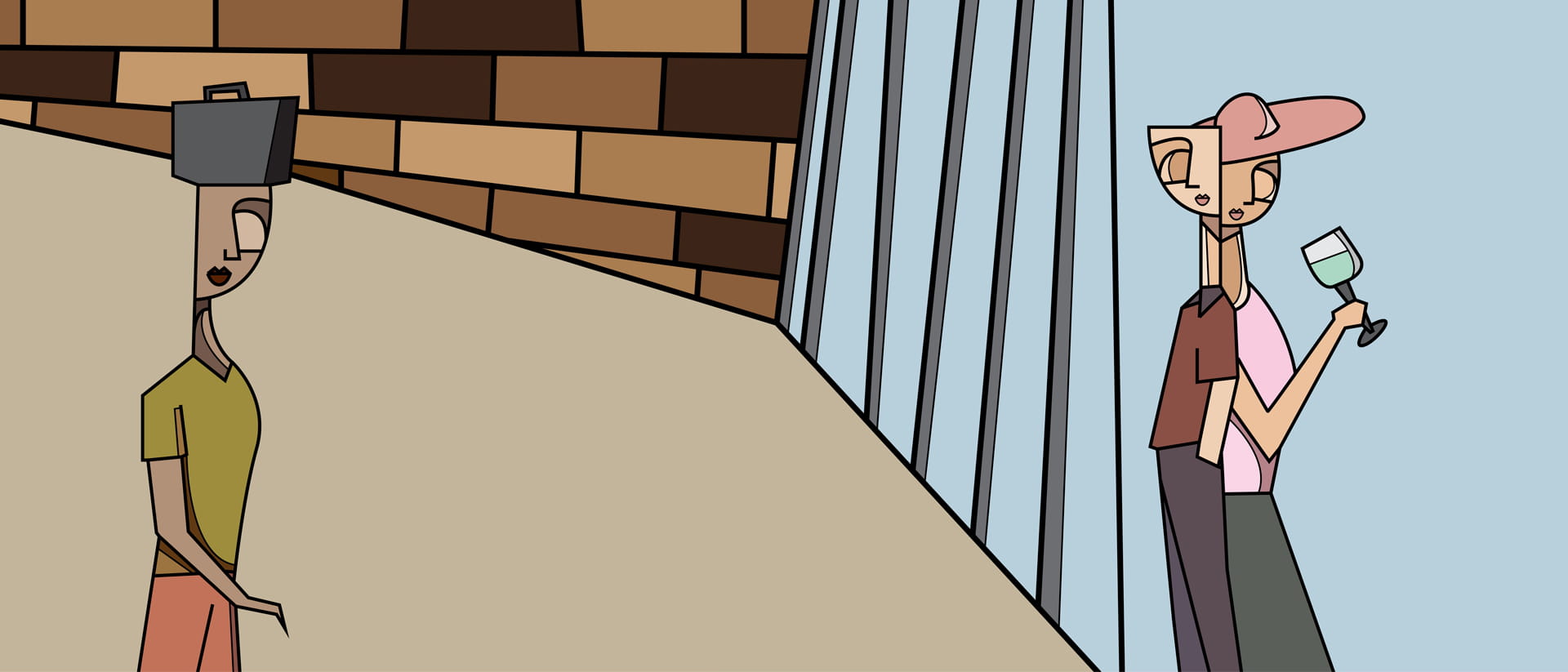

He was surprised, however, when he saw the high grey fences and the low sand-coloured building, which had no windows, only a clerestory window. Even so, this emergency location surrounded by olive trees felt like heaven. In Libya, where Samuel had hoped to find work, he had been kidnapped, sold at a slave market and forced to work day in, day out on a tomato farm.

After eight months, he managed to escape, in the chaos of fights between two armed groups. A Libyan who felt sorry for him said he could take him to a safe place in Egypt. It was not until he was on the rubber boat that he heard they were going to Europe.

For more than two hours, Samuel kept himself alive by swimming in the sea, before being pulled aboard by one of Sea-Watch’s speedboats. When a boy who couldn’t swim pulled him under, he thought he was going to die. But he managed to drag him up and grab a life jacket. That’s how they both stayed afloat.

All queued up, they were led into the camp: past a doctor (drink a lot of water), a pile of clothes (the trousers fit him quite well), and then, blanket under arm, into a kind of sports hall, where as many as 300 bunk beds had stood.

That night, he dreamed about water.

The next day, Samuel was asked to register: if he wanted to apply for asylum? Yes, go ahead, he said. Not that he had ever dreamed of a life in Europe. Samuel was happy in Nigeria: he had a wife and a 16-year-old daughter there. But when his father died, his creditors came after him. His house was smashed to bits, and his face too. To avoid worse, he ran away.

Samuel strolled the Sicilian streets during the day; by six o’clock in the evening, he had to be back inside the fences of the camp. When he stumbled on an internet cafe one morning, he remembered the crumpled piece of paper in his pocket. He went inside, and sent “November 6 Incident” an invitation to become his Facebook friend.

At Charles Heller’s office, Geneva, Switzerland

When Charles Heller saw the footage for the first time, he thought: What have we done?

The massive inequality in the value of human lives – never before had he seen this so clearly.

And that made this case absolutely unique. Never before had Forensic Oceanography had such a wealth of information to help reconstruct an incident.

But Heller also immediately realised: it wasn’t enough. Because the images, however horrific, had not yet established that the European Union was legally responsible. There were no European customs officers shooting at migrants.

The images, however horrific they might be, had not yet established that the European Union was legally responsible. There were no European customs officers shooting at migrants

Heller worked closely with two lawyers: Violeta Moreno-Lax from Spain and Itamar Mann from Israel. They were convinced that they could present a case to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. Provided they could find a smoking gun: solid proof that Italy or the EU was actually controlling the actions of the Libyan coastguard. Evidence showing that these violations would not have taken place without the European migration policy.

Time was not on their side: a case must be filed with the Court in Strasbourg within six months of the incident. Nearly a month had already passed, and the case still had to be assembled from scratch.

And there was yet another crucial piece missing: the lawyers had to get in touch with the survivors intercepted by the Libyan coast guard. They needed to be able to show that Libya was not a country that was safe for returning migrants.

In the Tajoura detention centre, Tripoli, Libya

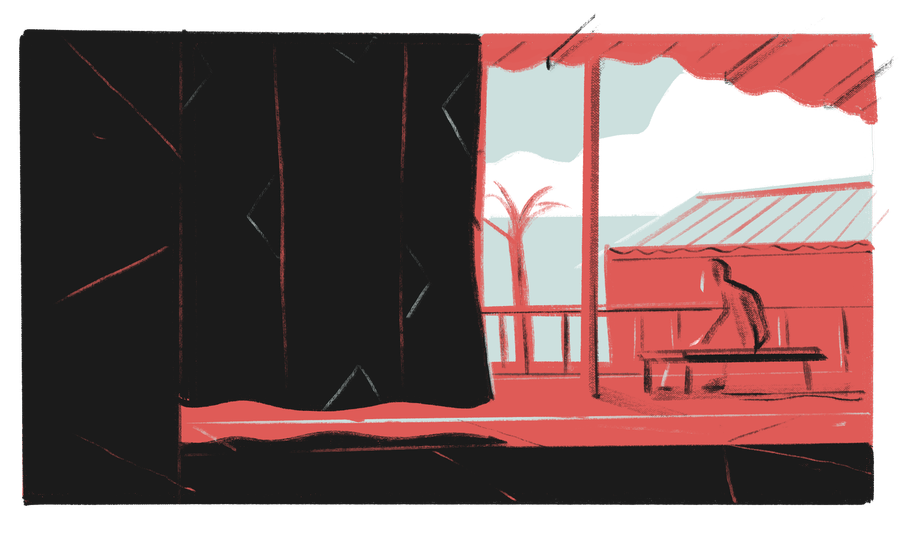

Patrick could hardly stand any more. He hadn’t seen the sun for two months – the UN official who promised to help him never came back.

A single moment has been running through his head on repeat: he’s standing on the back of the Libyan coast guard vessel, contemplating jumping into the water and swimming to the Sea-Watch ship. He had been afraid he wouldn’t make it. But if he had made it, he would have been in Europe by now.

Why didn’t he jump? Why didn’t he jump?

His cough had grown bad enough to wake him up at night. He needed urgent medical attention. One of his cell mates died that night. Even before the corpse was removed, people were fighting over who would get his mattress.

A few days ago, a couple of men had carried him to the door, hoping the guards would take him to a clinic. But they had chased him away from the door with a club. Patrick no longer remembered how he had gathered the strength to crawl back to his corner.

Patrick couldn’t understand why the UN people hadn’t come back. He had heard rumours: that the UN criticised the conditions in the prison and that the Libyans hadn’t let anyone else in since then. Some people called their family in Nigeria to send money: for about €1,000, you could buy your freedom.

Suddenly, there was a commotion at the entrance. “Release my countrymen, or it will be war!” he heard someone shouting, in a Nigerian accent. When the doors opened a little later, tears were streaming down Patrick’s cheeks. The bright light hurt his eyes so much. Himself, and about 400 other walking skeletons, were herded outside. The Nigerian ambassador stood there, crying. They were being taken to the embassy.

Three days later, on 7 January 2018, Patrick was on a plane for the first time in his life. He looked down and thought: I’ll never, ever come back here. He was on his way home. Without his wife, without his child. But alive.

At the Forensic Oceanography office, University of London, UK

When Heller hung up the phone, he knew: they were one step closer to their smoking gun. After weeks of trying, he had finally made it through to the Brigadier of the Libyan coastguard again. He had spoken to him earlier, shortly after the incident. But now Brigadier Masoud Abdel Samad had confirmed that they had received the coordinates of the rubber boat from Rome on 6 November. In other words: without the Italians, the Libyans would never have been there.

It was one of the many pieces of evidence that Heller and his colleague Lorenzo Pezzani had uncovered.

Another highlight: a photo they had found in the archives of the Reuters press agency, taken on 15 May 2017. Right in the middle was Marco Minniti, the Italian Minister of the Interior, surrounded by a horde of cameras. A new, light grey boat could be seen behind him. Clearly readable on the bow were the numbers 648.

Heller knew those numbers. After all, he had spent hours watching the Sea-Watch videos: it was the same boat that the Libyan coast guard used on 6 November 2017. The same boat that had capsized Patrick and Samuel’s balloon.

Moreover, internal EU reports showed that eight out of 13 Libyan crew members on boat 648 had been trained by the EU.

By now, a whole team of legal experts was involved. It looked like they would be able to pull together a case against Italy.

Now all they needed were plaintiffs, on whose behalf they could bring the case to court. And they only had three months left.

In an asylum-seekers’ centre near Florence, Italy

Samuel’s days had been the same for months. Every morning, he went to school to learn Italian. Every afternoon, he returned to the asylum-seekers’ centre and did ... nothing. He watched some TV – his roommate loved Russia Today. He read – mainly Italian children’s books from the library. He slept. And he waited for his asylum application to be reviewed. He was waiting to see his wife and daughter again.

But three weeks ago, on 21 March, something had changed. When school let out, he saw that he had a Facebook message. From his friend “November 6 Incident”.

Another message arrived.

In the days that followed, they talked on the phone. Julian told Samuel that he wanted to try to file a lawsuit with a group of lawyers, so that the EU could not send people back to Libya any more.

Samuel was glad he had something to do: he started sending messages to other survivors, asking whether they wanted to talk to Julian as well. The people who ended up in Libya were especially hard to find, Julian told him. But Samuel was smart and resourceful at tapping into his network: he quickly established contact with Patrick and three others who had ended up on the Libyans’ ship.

He hoped that he would be able to change something for all those people who were still in Libya.

And on the 13 April, he met Julian at the door of the asylum-seekers’ centre. He had flown in from Sicily, where he and two lawyers paid visits to other survivors to gather powers of attorney for the trial. He explained to Samuel that they wanted to start legal proceedings. That it would take years. But that they wanted to hold the Italian government responsible for what had happened to him. Julian asked him whether he would allow the lawyers to conduct the case on his behalf as well.

Samuel was a bit worried: would this affect his asylum procedure?

He would remain anonymous in all the documentation, Julian assured him. The Italians would not know who he was.

Samuel trusted Julian. If Julian said it would be a good idea, he was in. Samuel answered a long list of questions – about why he left Nigeria, how long he had been in Libya, what exactly happened on 6 November. He watched the video footage on Julian’s laptop, and pointed himself out on the screen: that’s me floating there; that’s me being pulled out of the water.

And then he signed document after document, all sorts of paperwork, signing his name again and again and again.

At Julian Köberer’s home, Frankfurt, Germany

It was all over the news. In the Italian media, on Reuters, on Voice of America, in Nigerian newspapers. “17 Nigerian migrants sue Italy for returning them to Libya.” That morning, the case had officially been sent to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. From behind his laptop, Julian watched a livestream of the press conference in Rome, where Heller was speaking. He couldn’t be there himself: his brother was visiting from Australia.

Julian had run out of steam. He had spent the past few months chatting, calling, apping with the migrants. Although they had to work under time pressure, he didn’t want to make them feel like he was only “using” them for the trial. So he asked them how they were doing, what was on their minds. Where necessary, he referred them to pro-bono lawyers to help with their individual asylum cases.

His contact with the men who were still in Libya was the hardest for him, emotionally – perhaps too hard. The stories of torture, slave trade, electrocution. The palpable fear on the phone.

His four-year-old nephew tugged on his arm, wanting to play. He closed the lid of his laptop.

Julian needed a break.

At Patrick’s mother’s home, Benin City, Nigeria

Patrick sat on his mattress, in his mother’s house, holding a card in his hand. The ornately scripted letters spelled out the name of his wife. And another man’s name. They would be getting married on Saturday.

Since he had returned to Nigeria, his wife would have nothing to do with him. She had returned from Libya a little before him. They had barely talked about their drowned daughter, but Patrick felt that she blamed him.

He still had all her baby clothes, wasn’t sure what to do with them.

Patrick remembered the heat when he got off the plane a year ago in Port Harcourt, in south-eastern Nigeria. It brought back that same feeling, the feeling that had driven them to leave: here in Nigeria, you work like a giant and earn like an ant.

When he arrived at his mother’s house, the door was closed. He walked around to the back. His mother screamed – a burglar! “It’s just me, mama. It’s Patrick.” She started crying. When he looked at himself in the mirror that night, he understood why.

He sat on the floor of the living room and ate the food his mother put before him: swallow and egusi. His little brother and nephews just looked at him. Nobody asked questions.

What he was most ashamed of was going back to his tailor shop. He had handed the shop over to his best apprentice. In the eyes of that boy, Patrick saw that he had also ruined his dreams by coming back. He had failed. Everything had to be rewound, including their lives.

When a lawyer had asked him last year if he wanted to participate in the trial, he was glad that someone still remembered him. But he hadn’t heard anything about the case for months.

He had watched the video of 6 November at least 100 times, since it appeared two weeks ago on the site of the New York Times. He could see himself standing there, on the aft deck of the Libyan boat, in his green shirt. Some days, he thanked God he didn’t jump – he could have been killed. On other days, he cursed himself – he could have been in Europe.

In his dreams, he was always in Europe. That was where his potential lay, he could feel it. But he knew that the EU was cooperating with the Libyans for a reason: they didn’t want people like him.

The European Court of Human Rights, Strasbourg, France

Their case is now lying somewhere on a desk in Strasbourg. It has been there for almost two years now.

For the first year, Charles and the lawyers had only a case number: 21660/18. Apart from that seven-digit number – which showed that the case at least met the European Court of Human Rights’s procedural requirements – the silence was deafening.

The court in Strasbourg can take up to two years to send the case to the Italian authorities – but in actual practice, complete radio silence for almost a year is very unusual.

Charles and the lawyers attribute the delay to how incredibly politically sensitive the case is: the judges know that Italy’s possible conviction would send shock waves throughout the EU, going far beyond putting a stop to the Italian cooperation with Libya. All deals with neighbouring countries such as Turkey, Morocco, Tunisia and Libya – the stopgap measures designed to curb migratory flows – would be opened up to legal challenge. And the Court would prefer, the lawyers believe, to postpone such serious consequences, in the hope that European politicians would resolve the problem themselves.

But so far, that’s not what has happened. In fact, the situation has gone from bad to worse.

At sea, migrants in distress are increasingly left to their own devices. At the beginning of 2019, the Sea-Watch 3 was the only European rescue vessel still plucking drowning people from the waves. On several occasions, it sailed off European coasts for weeks before receiving permission to drop rescued migrants off in a European port. In February 2019, the boat was chained up in Sicily by order of the Dutch government. And in March, the EU also stopped its human trafficking counter-operations in the Mediterranean. The only “rescue” that remains is the Libyan coast guard. But since Libyan commander Khalifa Haftar launched an offensive on Tripoli, the already unstable country has become even more dangerous. Anyone trapped in Libya now is in the middle of an explosive civil war. Tens of thousands of migrants are still stuck there, at the very least.

In Strasbourg, there has been a first round of "observation exchanges" with the Italian government. Each time, it takes months to wait for a reply. It is still unclear if the Court will actually hear the case. And so Charles Heller, sometimes nearing desperation, sits waiting for a message from Strasbourg.

Of the 17 migrants taking part in the trial, two are back in Nigeria, one is still in Libya, one in Spain, one in France and eleven in Italy. Samuel was allowed to appear before a committee regarding his asylum procedure in January 2019. He’s still waiting to hear the outcome.

This article was created with the help of the Stimulation Fund for Journalism and first appeared on De Correspondent. It was translated from the Dutch by Joy Phillips.

Dig deeper

Europe is the promised land – and nothing will convince these migrants otherwise

Many migrants want to get to Europe – and no costly EU awareness campaign will dent their idealised vision of life there.

Europe is the promised land – and nothing will convince these migrants otherwise

Many migrants want to get to Europe – and no costly EU awareness campaign will dent their idealised vision of life there.