At the end of my introduction to this series, where I offered myself up as a political literacy guinea pig, I wrote: “Until we can better understand how politics works, including our own parts in its dysfunction, there’s no chance fixing it.”

To my mind, there seems no better starting point for understanding politics than to grapple with the word “democracy”. What does it mean and how should it work?

The word is easy enough to define. It comes from the Greek for people (demos) and power (kratos), translating as people power, or government by the people. Most of us know democracy as something like that. But things quickly get more complicated when we ask what exactly that means in everyday life.

If you’ve been following, you’ll know I appreciate British political theorist Bernard Crick’s ideas about the three elements of politics. They are: who gets what when and how, who has power over those decisions, and how well their related outcomes ensure everyone’s welfare. So “politics” describes the day to day of any group of humans whose lives are bound together by family ties and territory. “Democracy” describes only one way of tackling such questions.

Read this story in a minute

Ancient Greeks get star billing in the politics timeline, having tried several approaches to governance, conjured up a rich political vocabulary and doing us all a favour by analysing and recording their experiments. These included sometimes electing public officials and other times selecting them by lottery.

How the Greeks approached the challenge of governing is well documented but it’s hard, if not impossible, to compare that with what other societies did. Findings from the Americas show the sophistication and embedded knowledge of indigenous cultures before colonising Europeans overwhelmed them with their guns, germs and steel. What could we have otherwise gleaned from political systems there?

Then there’s ubuntu, the Nguni language word for a humanist philosophy and way of living from southern Africa. It’s most often translated as “I am, because you are”, a profoundly political concept which evokes the connectedness that exists, or should exist, between all people and the planet – a manifesto for inclusive government.

That I don’t know much about other political histories is because I learned little about them at school four decades ago and I haven’t done enough to look into them since. This goes some way to explaining my illiteracy. But I digress ...

Democracy is dead! Long live democracy!

Centuries of European colonial dominance transported Aristotle’s political definitions around the world. It helped that his ideas are apparently simple: democracy, oligarchy and tyranny meaning government by all, the few and the one respectively. Aristotle was a pragmatist. He reckoned the best a city of his time could hope for was some compromise between oligarchs and democrats, or rich and poor, with neither inclined to entertain the other’s desires or perspectives.

Eric Arthur Blair, better known under his pen name George Orwell, was much less pragmatic. He classed “democracy” among what he called “meaningless words”, those with several, contradictory meanings.

“In the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides,” Orwell wrote in his 1946 essay "Politics and the English Language".

“Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different.”

Maybe Orwell’s contemporary, Britain’s second world war prime minister Winston Churchill, was one of the people he had in mind. Churchill quipped that democracy was the worst form of government bar all the others ever tried, perhaps the world’s best-known quote on the topic. Not much help in understanding what it means, though.

Perhaps it’s foolish to pin a word from antiquity on our modern systems of public decision-making. Layers of complexity separate ancient Athens from today’s nation states – our political unit of choice of the last few centuries. Today’s governments, democratic or otherwise, face much larger-scale decisions whose impacts radiate out to more or less every other country on Earth.

We need to call these systems something, though, and government by the people, in representative or direct form, certainly enjoys mass appeal.

“Polyarchy” – government by many people – is an alternative term coined by US political scientist Robert Dahl. For him, every so-called democracy in history fell short of the promise implied by that name. I curdled at the term when I came across it. It’s hard enough to engage people in thinking about democracy, I can’t imagine anyone defending barricades for this unfamiliar upstart. But putting aside the label, which Dahl never really intended for popular use, his work at least set tests for the democratic qualities of any large-scale, real-world government.

Free and fair or pale, male, and stale?

For Dahl, a democracy requires six elements. These are: elected officials; free, fair, and frequent elections; freedom of expression; alternative sources of information; the right to organise politically; and, inclusive citizenship.

His second – the regular holding of elections “free and fair” – is perhaps the one expectation people have of a democracy. After all, elected officials, who make decisions that shape the lives of billions of people, arrive via … elections. All the others are democratic building blocks, each vital in its own way and always taking decades of struggle to secure but arguably playing second fiddle to the act of voting.

So what of free and fair elections then? What better case study for political literacy school than that of George W Bush’s first US presidential win in 2000?

This was an election deemed too close to call on the night and which ran on for days in chaotic, contested vote counts in Florida. The ballots cast in that one state would decide whether Bush or his Democratic rival, Al Gore, would run the country for the next four years. The controversy spawned multiple legal challenges, meaning US Supreme Court judges effectively decided the outcome.

Investigations later revealed tens of thousands of names were wrongly stripped from Florida voter rolls prior to the poll, mainly African Americans who would have more likely voted Gore than Bush. It’s hard, by any stretch of the imagination, to qualify that election as either free or fair. Things have since got worse.

Work by the British journalist Carole Cadwalladr revealed how electoral manipulation delivered via social media has gone global, and on an industrial scale. Her investigations into British data research company Cambridge Analytica (CA) shows it harvested information from millions of Facebook users to deploy in electoral campaigns for its clients. Included among them are Donald Trump, and his successful run for president in 2016, and the UK Brexit referendum of the same year. While CA’s work was exposed and the company shut down, its techniques and others like them remain available for those with the cash.

And to those with cash, while success at the ballot isn’t always guaranteed, deep pockets buy plenty of political influence. This is a problem as ancient as it is pervasive, as Roslyn Fuller lays out in Beasts and Gods.

The distorting – if not corrupting – influence of money helps to explain why elected representatives rarely reflect the societies they are meant to represent but rather their richer members. Consider the representation of women in government. Though their share of seats in legislatures worldwide is growing, they still represent fewer than a quarter of deputies. The same goes for minorities – whatever they may be, wherever they may be. So while, for example, western countries are becoming more ethnically, racially and religiously diverse, their legislators generally haven’t kept pace with these changes. If the current US presidential race is anything to go by, the face of democracy is still pale, male and stale. In parts of the world where people of colour are the majority, male and stale usually covers it.

A bad case of trust deficit disorder

The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) used something like Robert Dahl’s tests to rank 165 independent states and two territories in its 2019 Democracy Index. Leading the field was Norway, first in a top five featuring Iceland, Sweden, New Zealand and Finland in descending order. The world’s major powers – the United States, China and Russia – scored 25th, 153rd and 134th respectively.

The EIU assesses electoral process and pluralism, the functioning of government, political participation, political culture and civil liberties. That may seem comprehensive but at the core of this assessment is an unquestioned devotion to the idea of elections – which we have seen are far more problematic than first meets the eye.

If we were to assess countries by a different metric, I would suggest something like trust. Here, the data doesn’t look so good. Established democracies today show lower levels of trust than three or four decades ago. Economic crises are a major factor but so too are elections, or rather the inflammatory things that candidates do or say to get elected versus what they do in office.

Antonio Guterres spoke in 2018 of the world suffering a “bad case of trust deficit disorder”. “Trust is at a breaking point,” the UN Secretary-General said. “Trust in national institutions. Trust among states. Trust in the rules-based global order. Within countries, people are losing faith in political establishments, polarisation is on the rise and populism is on the march.”

Dahl’s six measures of democracy don’t include “trust”, perhaps because his life spanned a period of US history when successive generations generally expected their offspring to live better lives than they had. By his death at 98 years old, in 2014, that could no longer be taken for granted. That year, in both the United States and the UK, previously improving life expectancy and infant mortality rates went into reverse. Social geographer Danny Dorling attributes the worsening mortality rates in the UK to austerity politics – the double hit of governments responding to severe economic crisis by cutting public spending while giving tax breaks to business and the better-off.

The idea that poor-quality government might be lethal to its “demos” hardly needs explaining today. The coronavirus has exposed the poor leadership of both Donald Trump and Boris Johnson – skilled elections winners who have struggled to keep their citizens safe. At the same time, the few women leaders there are in charge of countries seem to have navigated well through the pandemic.

So where does that leave us with democracy, and what it means for people’s lives? It’s the question I opened with, and this answer by Roslyn Fuller is a fitting closure: “Democracy comes from the Ancient Greek and it means people power. That’s very different from the understanding that democracy is hearing all voices or giving people a say.

“One of the two keywords is ‘power’. The final power always comes back to the people. Someone ultimately has to have the power in society and, if it’s not the people, who is it?”

It’s a great question that begs a second: if we’re dissatisfied with our systems of government, and would like to move towards something more like “government by the people”, where might we start? Can we fix democracy?

We’ll look at that next.

About the images

The series National Trust by photographer Jay Turner Frey Seawell shows the theatrics of modern day US politics. Looking at the relationship between power, politics and media, Seawell photographed the topic as if we’re looking at a movie scene, resulting in a photo series that seems to be stranger than fiction. The shrill contrast between this modernity and the architecture that references ancient western empires in the background enhances the absurdity of the experience. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

About the images

The series National Trust by photographer Jay Turner Frey Seawell shows the theatrics of modern day US politics. Looking at the relationship between power, politics and media, Seawell photographed the topic as if we’re looking at a movie scene, resulting in a photo series that seems to be stranger than fiction. The shrill contrast between this modernity and the architecture that references ancient western empires in the background enhances the absurdity of the experience. (Lise Straatsma, image editor)

Dig deeper

An Athenian remedy: the rise, fall and possible rebirth of democracy

Governments chosen by elections face profound challenges the world over, including in Greece, the birthplace of democracy. So where better to look for potential solutions than modern-day Athens?

An Athenian remedy: the rise, fall and possible rebirth of democracy

Governments chosen by elections face profound challenges the world over, including in Greece, the birthplace of democracy. So where better to look for potential solutions than modern-day Athens?

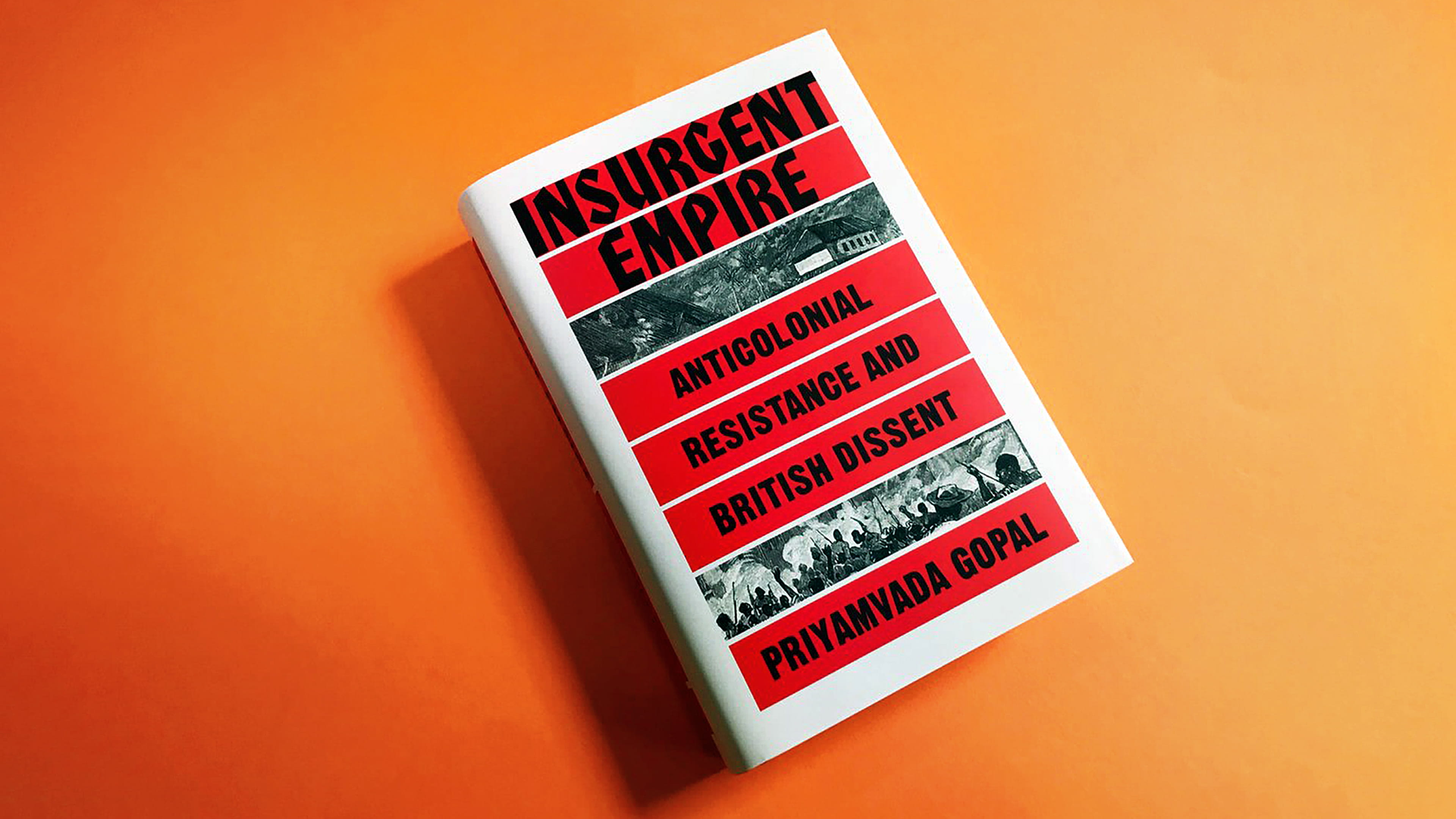

First rule of fight club: power concedes nothing without a struggle

In an interview that spans continents and centuries, Cambridge University academic Priyamvada Gopal connects the legacies of empire to present day struggles – be they to prevent climate catastrophe, or win self-determination. Class is in session!

First rule of fight club: power concedes nothing without a struggle

In an interview that spans continents and centuries, Cambridge University academic Priyamvada Gopal connects the legacies of empire to present day struggles – be they to prevent climate catastrophe, or win self-determination. Class is in session!