Early last year, I found myself on skis for the first time. As long as I could remember, I’d thought of winter sports as not my thing: too expensive, too posh, too much beer during the après-ski. But there I was, on a practice slope in Austria, surrounded by small children fearlessly whizzing past while my fellow travellers descended a black run some way further up. I can’t say I emerged as a natural talent, but I made it to the bottom in one piece, and after two days of falling, swearing and climbing back to my feet, even I was making reasonably controlled turns and able to go down a piste without too many falls.

Right after that first successful descent, I took a cable car to the valley. The day was coming to an end, I had the cable car to myself, the mountain mists closed behind, and ahead of me appeared a landscape that wouldn’t have looked out of place on a box of Caran d’Ache colouring pencils. Bright blue sky, dark green pine trees, snow-capped mountaintops glistening in the sun.

In the silence, countless tiny figures in shocking pinks, reds, blues and blacks slid beneath me on skis, snowboards and the odd sledge. And you can think what you will of winter sports – decadent, cliche, environmentally unfriendly, the Sisyphean futility of climbing up only to slide down, up and down and again – but I chose rapture, or rapture chose me.

A mantra for our time: new experiences, not repetition

Call it the late bloomer’s ultimate advantage: for those who wait long enough, there’s always something new to come. That evening, somewhere between drinking my last white beer and sinking into the soft mattress of our Austrian chalet, I wondered why skiing struck me as so wonderful. Was it just the thrilling feeling in my gut as I slid downhill? Or was it also, perhaps mainly, the excitement of a new experience?

Because experiencing something new, doing something for the first time, gave me the pleasant sense of being right in sync with the zeitgeist. If our epoch holds one thing dear, after all, it’s the belief that in order to live a rich, full life, we should accumulate as many new experiences as possible. Although most of us are happy attending the same festival year after year, or going on holiday to the same seaside town, would lovingly work for the same boss for years (if only we could), and look forward to the same takeout each Friday, we’re encouraged to do exactly the opposite.

“Try something new every 30 days,” says a Google engineer in a Ted talk with an audience of millions. “Visiting New Places Has Major Psychological Benefits,” reads the headline on a popular travel website. While revisiting a beloved spot is “unlikely to aid self-improvement”, the accompanying article proclaims, visiting an unfamiliar place “challenges your brain in new and interesting ways”. Seek out new experiences together advises many a relationship counsellor – because routine is the beginning of the end.

We’re told, over and over again, to go on an adventure. We are exhorted to discover new parts of our neighbourhoods, broaden our horizons, and squeeze everything there is to be had out of life – rather than sticking to what we already know.

Why? For anyone doing something for the first time, time slows down, and consciousness works at full capacity. There’s a neat evolutionary explanation for this: our brains are hard-wired to pay extra attention to firsts – to stay alert to possible dangers, to derive lessons from the unknown. When we do something we’ve done hundreds of times before, we’re less attentive – and our minds retain less from the cognitive experience.

That’s precisely why first times often occupy our memory’s hall of fame. We may remember, in detail, the first time we kissed someone, got on a plane, smoked a joint, rode a horse, had a life-changing insight, patched together a broken heart, were awestruck by the sight of a particular work of art or the sound of a particular piece of music. Memories of second, third or nineteenth times are usually fuzzier around the edges.

Renewal is the mantra, however paradoxical or ironic that may sound. Because even beyond the bounds of personal happiness, the new and the novel are great goods – especially in cultures that pride themselves on past inventions and discoveries, cultures with a sacred belief in progress.

And so we’ve placed creativity – the making and inventing of new things or processes – on an enormous pedestal. Many of us take innovation to be the engine driving the economy – and every entrepreneur wants to be their own version of the first man on the moon.

No innovation without repetition

I won’t be the first to observe this, but doing things again is at least as important as doing things for the first time. We do the vast majority of things more times, many more, than once. In fact, first times stand out because repetition is the norm. If you write off repetition, you’re writing off pretty much all of life.

But repetition isn’t just the background against which the new stands out. It’s often a necessary condition for it.

But repetition isn’t just the background against which the new stands out. It’s often a necessary condition for it

Small children, inexperienced by nature, encounter new things all the time. To help them navigate this rush of novelty, parents and parenting experts swear by routine – a fixed rhythm to the week and the weekend, every evening the same slogan of brushing teeth, story, banishing nightmares, lights out and one last wave goodnight. Always in precisely that order, never a step different.

Children are creatures of habit, but the same is true for adults. Artists, engineers, innovators – those who are celebrated for their innovation-lust – generally swear by routine. It’s only by getting up at exactly the same time each day, having the same breakfast, completing the same round of running and putting on the same grey T-shirt that they’re able to make new things.

In their case, repetition is great for precisely the same reason that new experiences are great: what we already know costs us less attention and energy than the unfamiliar – and therefore automatically leaves room for new ideas to emerge.

Innovation is a form of repetition too

In other areas as well, repetition is what allows innovation and improvement to take place. Nine times out of 10, innovation arises from building step by step on what is already there – a form of repetition, with minuscule variations. And such repetitive activities as maintenance and preservation regularly lead to innovation, too.

Companies like to be pioneers: it gives them a “first mover advantage” and enables them to claim a large market share. But economists now realise that there is also something to be said for the second mover advantage: those walking a well-trodden path can learn, for instance, from the mistakes their forerunners made and avoid making them themselves.

Speaking of learning: that, of course, is largely made up of repetition as well. To practice is to repeat, again and again and again – to rehearse and rehearse until we’ve internalised the skill or story we’re trying to master.

Athletes in training, students cramming for exams, infants just learning to walk: repetition is the number one precondition for their performances, chances of success, and developing motor skills.

And in science, that collective quest for new and better knowledge, repetition plays a crucial role. Researchers prefer focusing on groundbreaking research to replicating studies by others – there are more subsidies available, and more honour waiting down the line, for venturing into the great unknown.

But only when studies are repeated by other scientists do we know whether their conclusions hold. In recent years, thanks to such replication studies, many claims in the social and natural sciences have perished – from the effect of a bold posture on performance to the idea that reading fiction makes you more empathic. Repetition is what distinguishes a fluke from an underlying reality.

The power of repetition

Humans yearn for more than just learning, innovating and achieving, of course. But there, too, the things that make life worthwhile – friendship, for instance, or love – are inconceivable without repetition. Psychologists have known for at least half a century that “repeated exposure of the individual to a stimulus object” causes positive changes to our attitude to that stimulus: the “mere exposure effect”, as it’s known in the field.

Why do we tend to make our closest friends at secondary school and in college? Because we see our fellow students every day, year in, year out.

Why do parents love their children? Because they care for those children daily from day one, and while providing that care they make the hormones that are a precondition for attachment.

And love? As someone once remarked to me, you meet the love of your life for the first time only once, and all the rest is maintenance. You have to somehow sustain your relationship for decades, day in and day out, over and over. (“Love doesn’t just sit there, like a stone,” writes Ursula K Le Guin: “it has to be made, like bread; remade all the time, made new.”)

Why do parents love their children? Because they care for those children daily from day one

And sure, that maintenance is easier and more fun if every now and then you do something new together. But doesn’t love also consist precisely of the communal routines, the little shared rituals, the unnamed, almost automatic repetitions – the fact that you turn out the lights in the living room and leave our son’s bedroom door open just a crack, that my legs find yours in bed every night, again and again and again?

There’s pleasure in repetition, cognisance in recognition.

For that very reason, change can startle people: think of the person who won’t eat what she doesn’t know, or the fanatical defender of traditions ripe for review. Politicians know that there are votes to be won with an appeal to what is old and familiar. And they know that this message is most effective when it is repeated endlessly: repetition is the foundation beneath propaganda.

A repetition is rarely a copy

Repetition and innovation are in no way mutually exclusive: in fact, they require and cause each other. And if you look at it like that, it turns out that repetition rarely brings us “more of the same”; it almost always brings us something different. Or rather, something new.

Music is a good example. Musicians and, in their wake, musicologists know better than anyone that repetition is crucial for our perception – and appreciation – of music. The more often we hear a song, the more we’re inclined to love it – that’s the mere exposure effect in action again.

But if you listen to a piece of music several times, you also hear something else – you pay more attention to subtleties or details, for instance, precisely because the brain doesn’t have to put all its effort into digesting the melody and the major lines.

And listening to music repeatedly changes the way we listen, too. Instead of passive listeners, we become active participants, already knowing what’s to come, anticipating and expectant.

I’m put in mind, again, of small children, how they love to sing the same song or read the same book several times in a row, how much they seem to love it when the lyrics or story turn out exactly as they did before. “NO!” they yell, when you change the words of a lullaby, or secretly try to skip a couple of pages. They’re part of the narrative, they join in – because they’ve heard it all before.

And isn’t that always the way repetition deviates from the first time? The second, third or hundredth time you see, do, hear or experience something is almost inevitably a richer experience than the first time. Because you have expectations based on previous occasions. Because those expectations either are or aren’t met – which may be satisfying, surprising or annoying, but in any case adds value.

It’s not easy to see this, when repetition counts mostly as innovation’s boring little sibling, but a repetition is never an exact copy of what went before. Because we aren’t the same: we’re changed by what came first, have become new people who look at things differently. You can’t step into the same river twice, nor can you visit the same campsite twice (let alone four times).

This means that every repetition is a new experience in itself. The expectations you have, sometimes fulfilled and sometimes not, are new. The recognition is new. Every performance of a shared ritual makes the relationship more layered than before. Every descent enables the body to ski more fluently than the previous attempt. Every play-through brings more subtleties to the attention than the previous listen. It’s all new.

This is a smaller, more modest sort of innovation, written on a palimpsest instead of a blank sheet. That makes it harder to observe, less likely to be the subject of conversation, of advice, of odes. It isn’t grand or all-consuming, but shows itself in small increments of depth, weight and strength.

It is an innovation which isn’t easily recognised as such, if only because we’ve never really learned to think of it that way. If we’re constantly encouraged to go in search of the great unknown, of what is radical and new, we can easily miss the more subtle change that comes with repetition.

So here’s the paradox: in order to appreciate repetition for what it is, we actually need a new sort of attention.

A better way of viewing repetition

For much of last year, I viewed my first time on skis as just that: a first time, satisfying and moving precisely because it was so very new.

But had I looked more carefully, more precisely, then I could have seen that that first time in fact consisted of lots of times. Of beginning time and time again at the top of the slope, hurtling down at a kamikaze pace, and dropping to the ground just before I hit the safety barrier because I didn’t understand the art of slowing down. My bends became a little sharper each time, my descent a little less out of control.

I was practising, repeating. I kept doing the same thing, kept beginning again, and it went slightly differently each time. That was an additional joy, or perhaps it was the core of it: those small progressions, the little surprises, the repetition with variation.

In a study published last year, participants were asked to revisit an exhibition they had just seen, or to put on a film they’d watched the night before. They were asked to indicate in advance how pleasant they expected the repetition to be.

We underestimate the pleasure of repetition because it’s never pointed out to us

As it turned out, the participants underestimated the pleasure they would derive from repeating their experience. They thought the second time around would be less enjoyable than it actually was.

We underestimate the pleasure of repetition because it’s never pointed out to us, directed as we are instead towards the mantra of innovation. And the point isn’t so much that we have to choose, for repetition and against innovation, or vice versa. The point – and I’m starting to sound like a broken record here myself – is that we need both, that they need each other, that they are polar opposites as well as extensions of each other.

It’s probably impossible to achieve the level of attentiveness we bring to first times the tenth or hundredth time we do something. But it’s entirely feasible to look more attentively at repetition, not to see it as a stumbling block but as a goal in itself. Not as a copy but as a variation. I suspect that the routines and rituals that make up daily life, the “grind” we’ve learned to fear, would feel less like a slap in the face to the zeitgeist, and more like something worthwhile all on its own.

Repetition brings you more than you think

Draw your own conclusions, said one of the researchers who conducted that study showing that people underestimate the pleasure of repetition. Instead of wasting time in search of yet another new experience, you might also choose to return to a film you’ve already seen, or to a restaurant you’ve already dined at. It might bring you more than you think.

There’s a difference between inattentively doing things again and doing things again by choice

And there’s the crux of the matter. Repetition is the norm: we’re constantly repeating things, whether we want to or not. But there’s a difference between inattentively doing things again and doing things again by choice. Conscious, attentive, deliberate. With the full awareness that this matters just as much, and with the willingness to see, hear and feel different things when you feel, hear and see them again.

The rapture that came over me early last year, in that cable car on my way to the valley, certainly had to do with the overwhelming quality of a completely new experience, the wonder of a first time. That can’t be reproduced, I get that. Even so, I would like to descend towards that valley once again after a long day in the snow, see the sun reflected anew on the snowy mountain peaks ahead of me, and again watch the brightly coloured miniature people speeding down the slope below. There would be things I recognised and things I saw for the first time, and I’m curious about both.

So while I still think winter sports are not my thing – too expensive, too posh, too much beer during the après-ski – I’d love to go again next year.

And the year after, again.

Et cetera, et cetera.

This piece first appeared on De Correspondent. It was translated from Dutch by Anna Asbury.

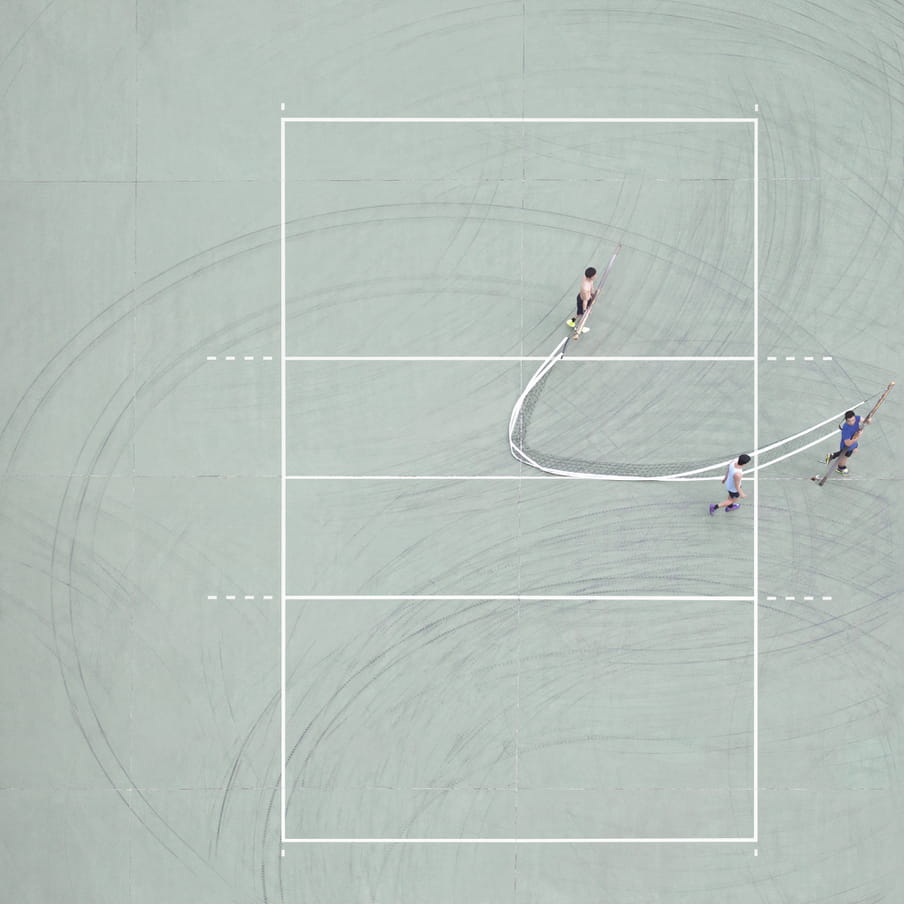

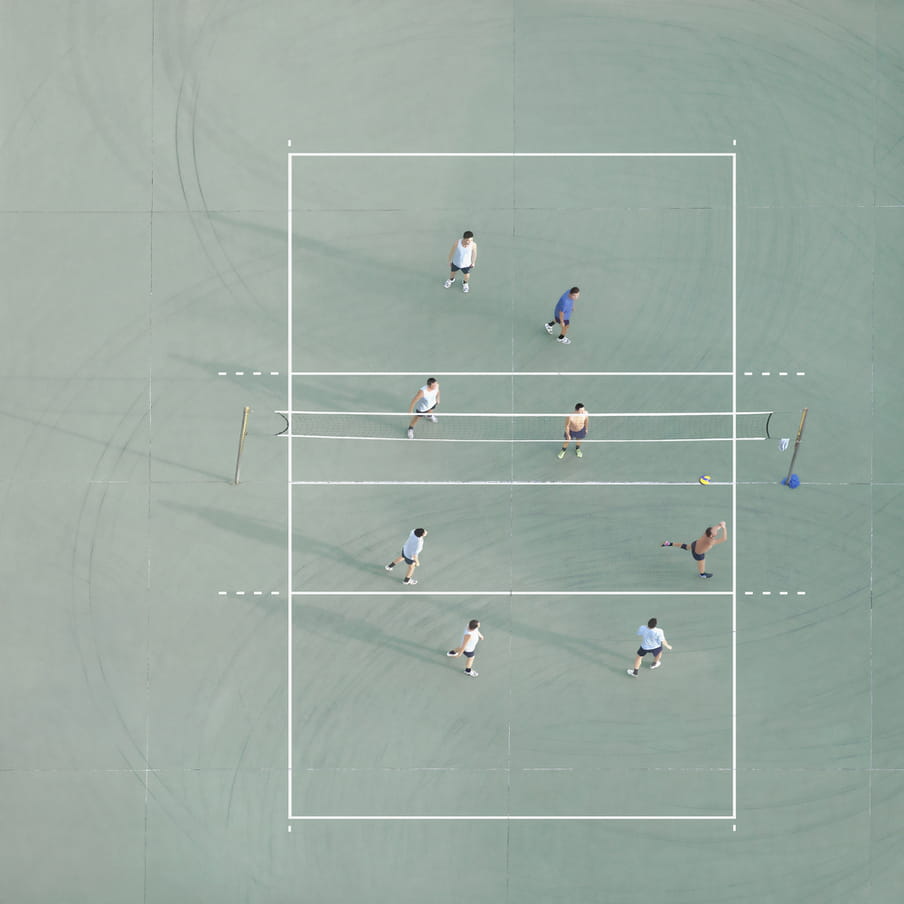

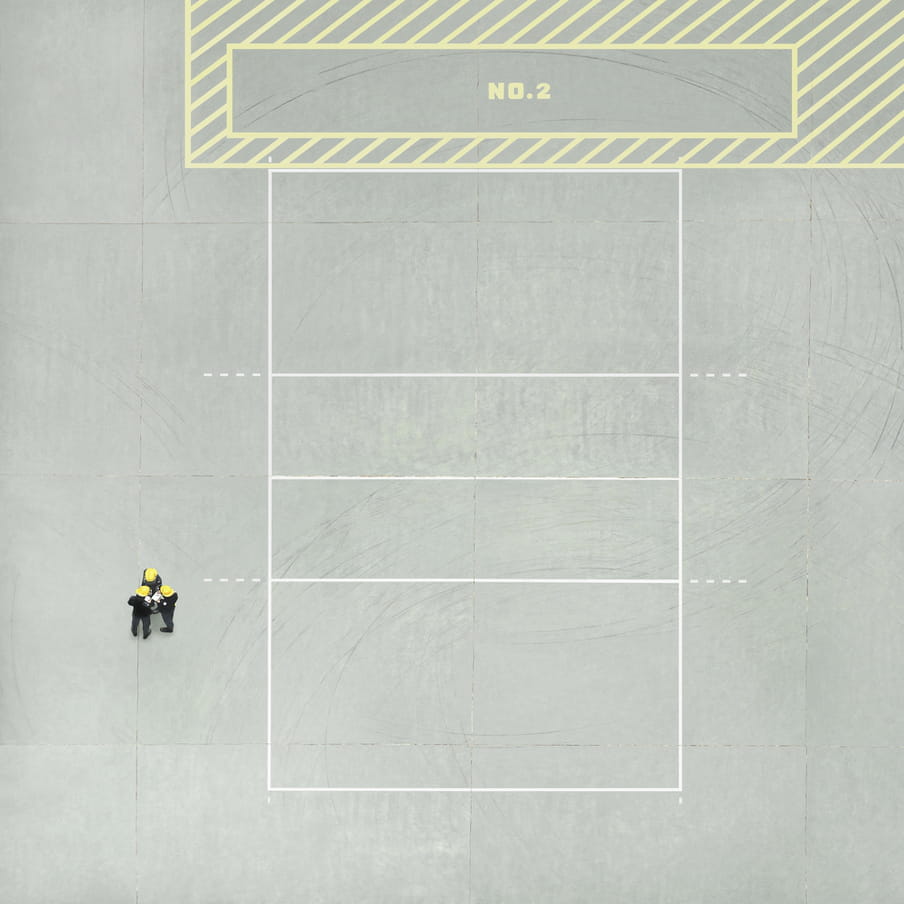

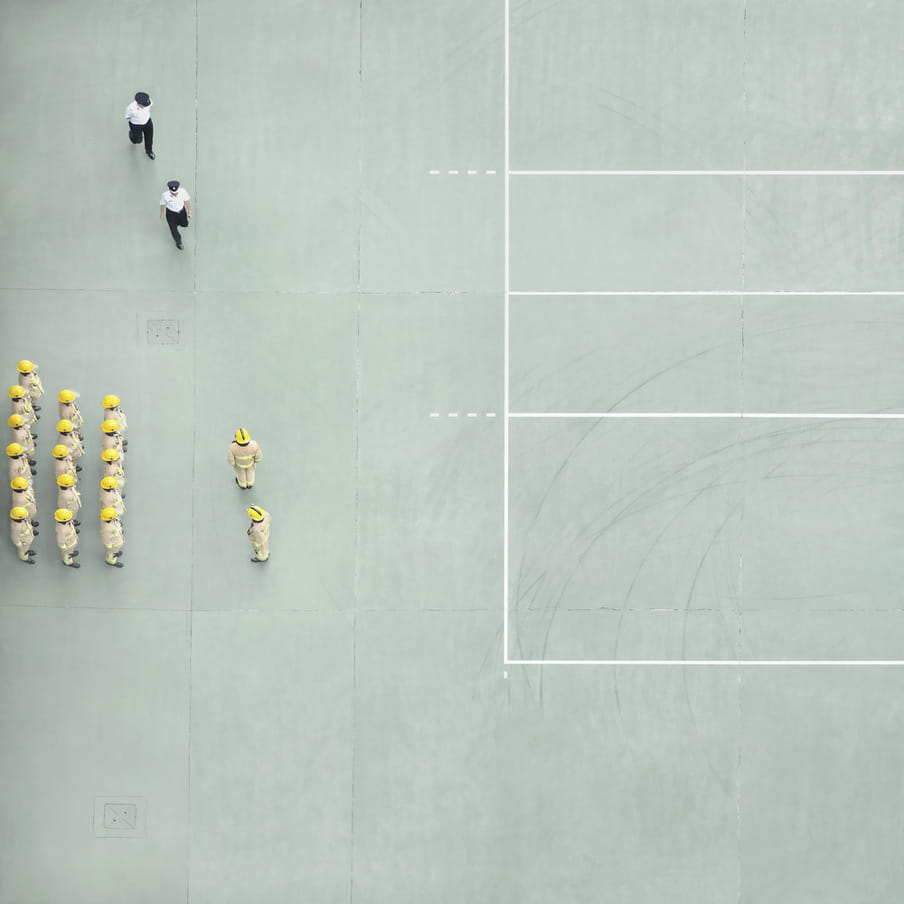

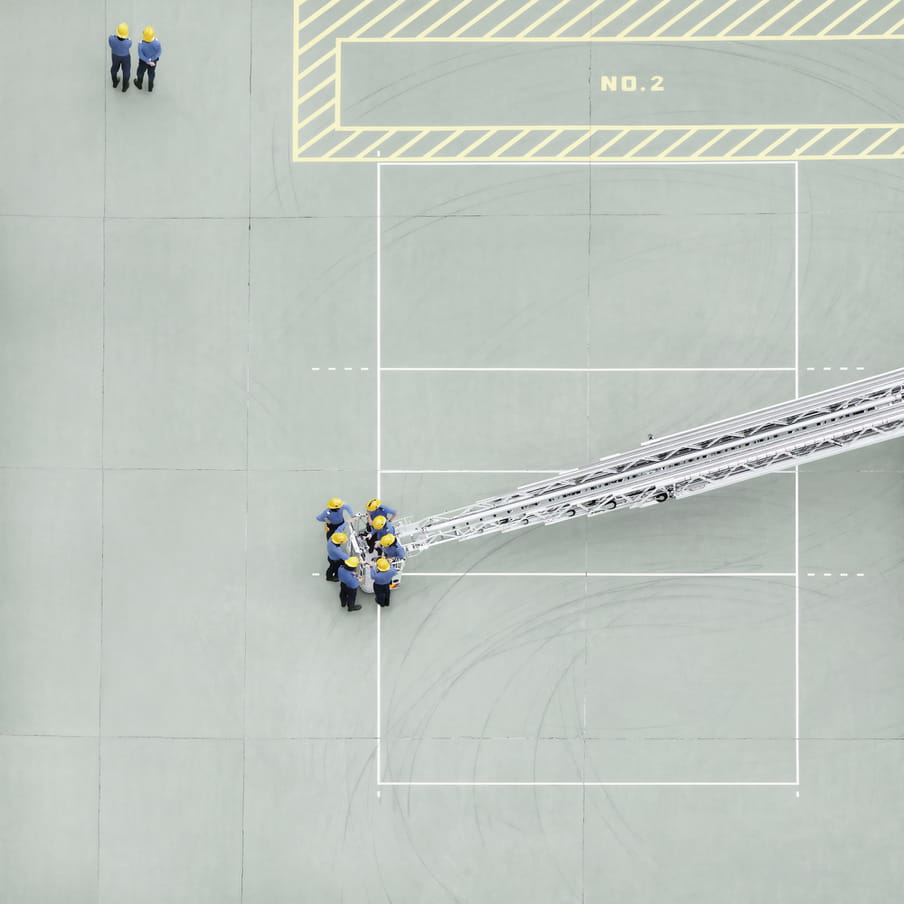

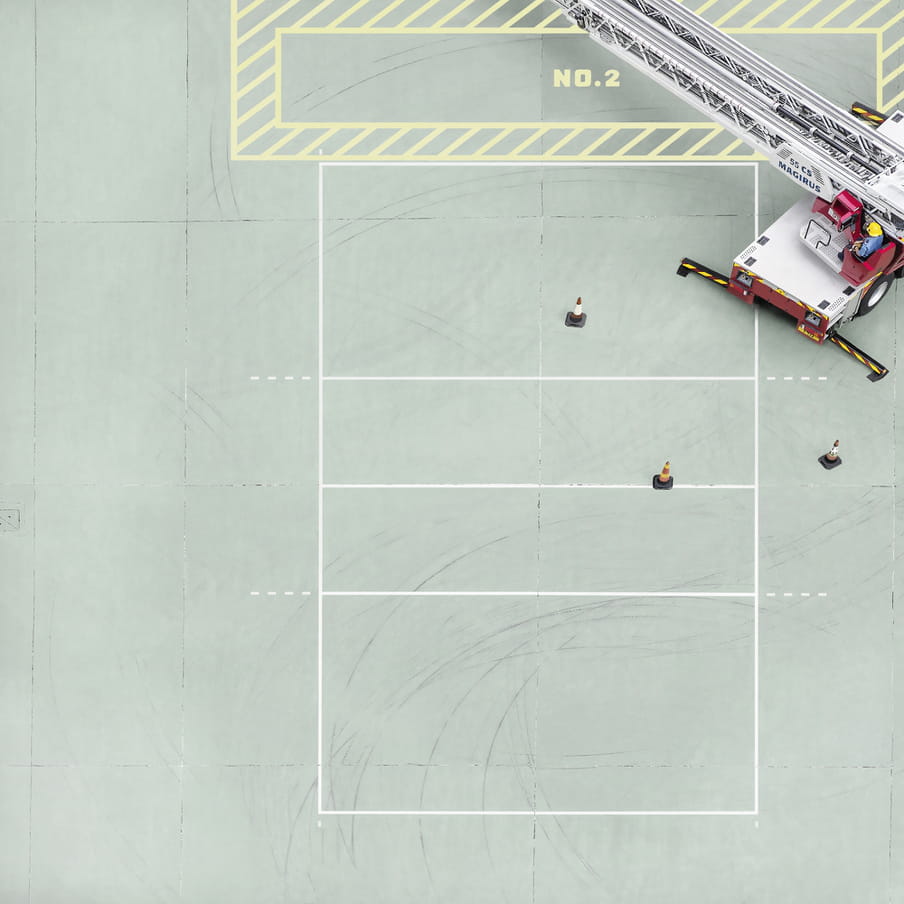

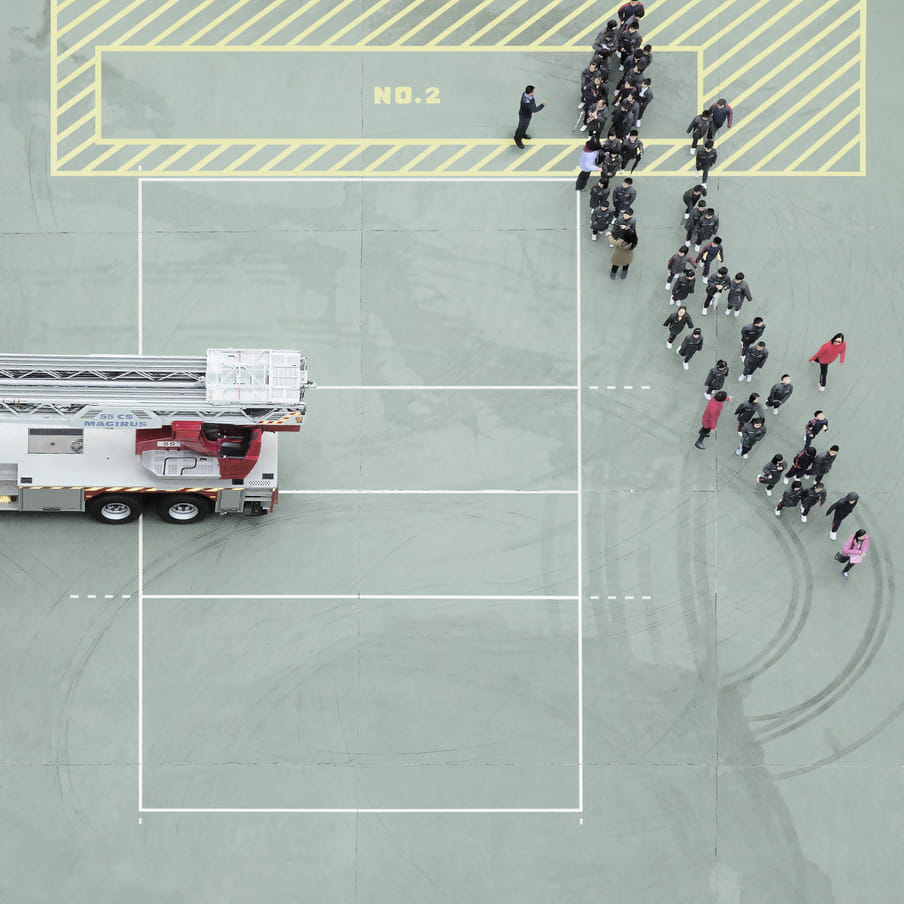

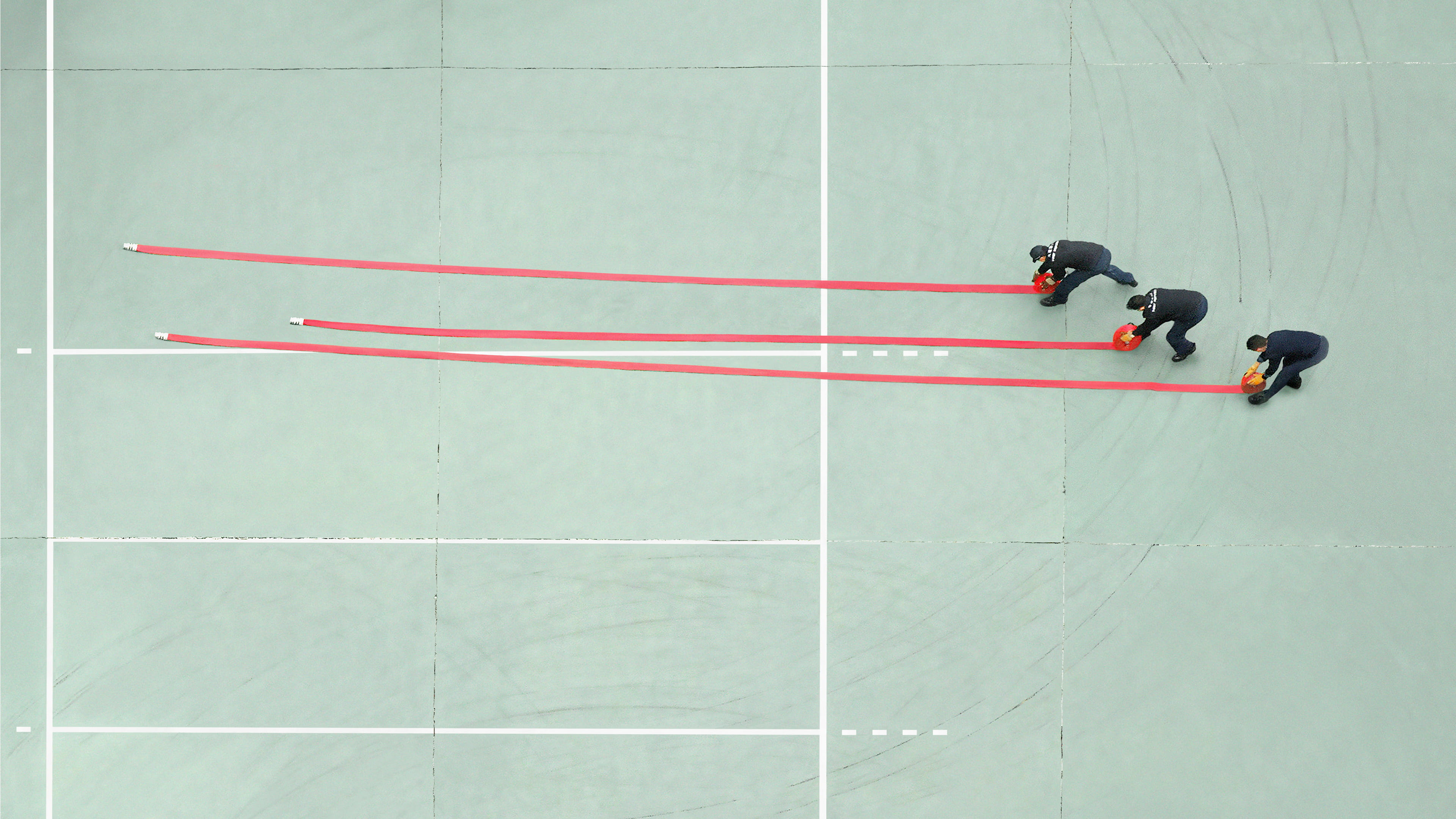

About the images

One day, artist Chan Dick peeked out of the window of his toilet. Next to his studio, on the dreary grounds of the Chai Wan fire station, a curious scene unfolded. A column of men in yellow suits were standing there simulating extinguishing a fire. They dragged hoses, climbed into steel structures, and marched over the asphalt. And every time he looked out of that window by his toilet, he saw them again: a procession of firefighters dragging hoses, climbing in steelwork, marching over the asphalt. Again, and again, and again. "I couldn’t get the images out of my head," Dick said. I even saw them with my eyes closed. And once I started taking pictures, I couldn’t stop.

About the images

One day, artist Chan Dick peeked out of the window of his toilet. Next to his studio, on the dreary grounds of the Chai Wan fire station, a curious scene unfolded. A column of men in yellow suits were standing there simulating extinguishing a fire. They dragged hoses, climbed into steel structures, and marched over the asphalt. And every time he looked out of that window by his toilet, he saw them again: a procession of firefighters dragging hoses, climbing in steelwork, marching over the asphalt. Again, and again, and again. "I couldn’t get the images out of my head," Dick said. I even saw them with my eyes closed. And once I started taking pictures, I couldn’t stop.

Dig deeper

How we turned into batteries (and the economy forces us to recharge)

Energy has become modern society’s holy grail, but what if we don’t want to spend our limited time on Earth constantly recharging and draining ourselves? In an age of punishing pressure to be productive, saying no is the opposite of negative.

How we turned into batteries (and the economy forces us to recharge)

Energy has become modern society’s holy grail, but what if we don’t want to spend our limited time on Earth constantly recharging and draining ourselves? In an age of punishing pressure to be productive, saying no is the opposite of negative.