It should go down in history as one of the strangest call-ups to join a national football team.

Until the day he was first selected to play for Wales, no one in Wales knew Jamie Lawrence and Jamie Lawrence knew no one in Wales. Jamie Lawrence was not born in Wales, had never played in Wales, and had no family in Wales. He did not speak Welsh, never played for Welsh youth teams and had no prior contact with the Football Association of Wales.

Jamie Lawrence had never even been to Wales.

Read this story in one minute

It was odd – you would expect any football association to do everything it can to keep track of potential players. You’d certainly expect this from a small footballing nation that can’t afford to waste talent, not if it wants to stand a chance against big countries. Especially when it comes to left-footed central defenders, a rare and sought-after type of player.

And yet Jamie Lawrence remained unseen – until he wasn’t.

In the afternoon of Monday 5 November 2018, Welsh national manager Ryan Giggs announced his squad for a crucial Nations League game against Denmark. The list of names on a sheet of paper handed out in the press room included one "J Lawrence". The journalists thought it was a spelling mistake: not J. Lawrence, but T. Lawrence. Tom Lawrence, the Derby County winger. But his name, T. Lawrence, was also on the list.

So who was J.?

Meet Jamie Lawrence of Arabia, Slovakian presidential candidate, bionic soccer player, defender against black holes

"J." turned out to be a central defender for the Belgian club Anderlecht. That was all Google had taught the journalists, when Giggs entered the room. From the press corps, BBC Wales football commentator Rob Phillips started with the obligatory first questions about the side’s star player, Real Madrid forward Gareth Bale.

Then he asked about James Lawrence:

Phillips: “You’ve had us all searching Google. James Lawrence, Anderlecht. Tell us how you came about him.”

Giggs: “We got made aware of him over the last six months or so. He’s gone under the radar.”

Phillips: “Is it someone you’ve been made aware of by a member of the public? Or is it Albert [Stuivenberg, Giggs’s assistant]...?”

Giggs: “No, it was someone at the Welsh FA.”

Welsh football fans who followed the press conference also turned to Google. There wasn’t much to work with. A short interview on Anderlecht’s site, some articles in Slovakian (where Lawrence had played for a club called AS Trenčín), as well as a host of more famous James Lawrences.

And so, hungry for facts, lacking any facts, the fans made up their own facts under the hashtag #jameslawrencefacts.

This imaginary James Lawrence was a force to reckon with. Endowed with a bionic foot, he finished third in Slovakia’s presidential elections, and saved the world from a black hole. Soon, #jameslawrencefacts had become a trending topic. At home in Brussels, the real Jamie Lawrence cried tears of joy at his odd new status of Welsh celebrity.

At home, in Amsterdam, Jamie’s father Steve Lawrence fought against another type of tears. At last, others saw what Steve had always believed: the exceptional talent of his son.

My son: statistic or person?

Steve spotted it when Jamie was only three years old, but then so did everyone else who saw the boy play in their London suburb of Queen’s Park: how easy he found it to compete with older children. When Jamie was four, he was a better footballer than most six-year-olds; by the time he was six, he would defeat nine year-olds.

Aged seven, Jamie joined the Arsenal Advanced Academy, a private football academy where Premier League side Arsenal often scouted for players. In the spring of 2000, Steve was watching a training session there when he bumped into a man who started a conversation that would change Steve’s life.

Unknown Man: "Is that your son?”

Steve: “Yes …”

Unknown Man: "He’s got talent. When was he born?"

Steve: "August 22nd …”

Unknown Man: "What a shame.”

Steve: "I beg your pardon?”

Unknown Man: “August 22nd? Then he’s not going to make it as a professional soccer player.”

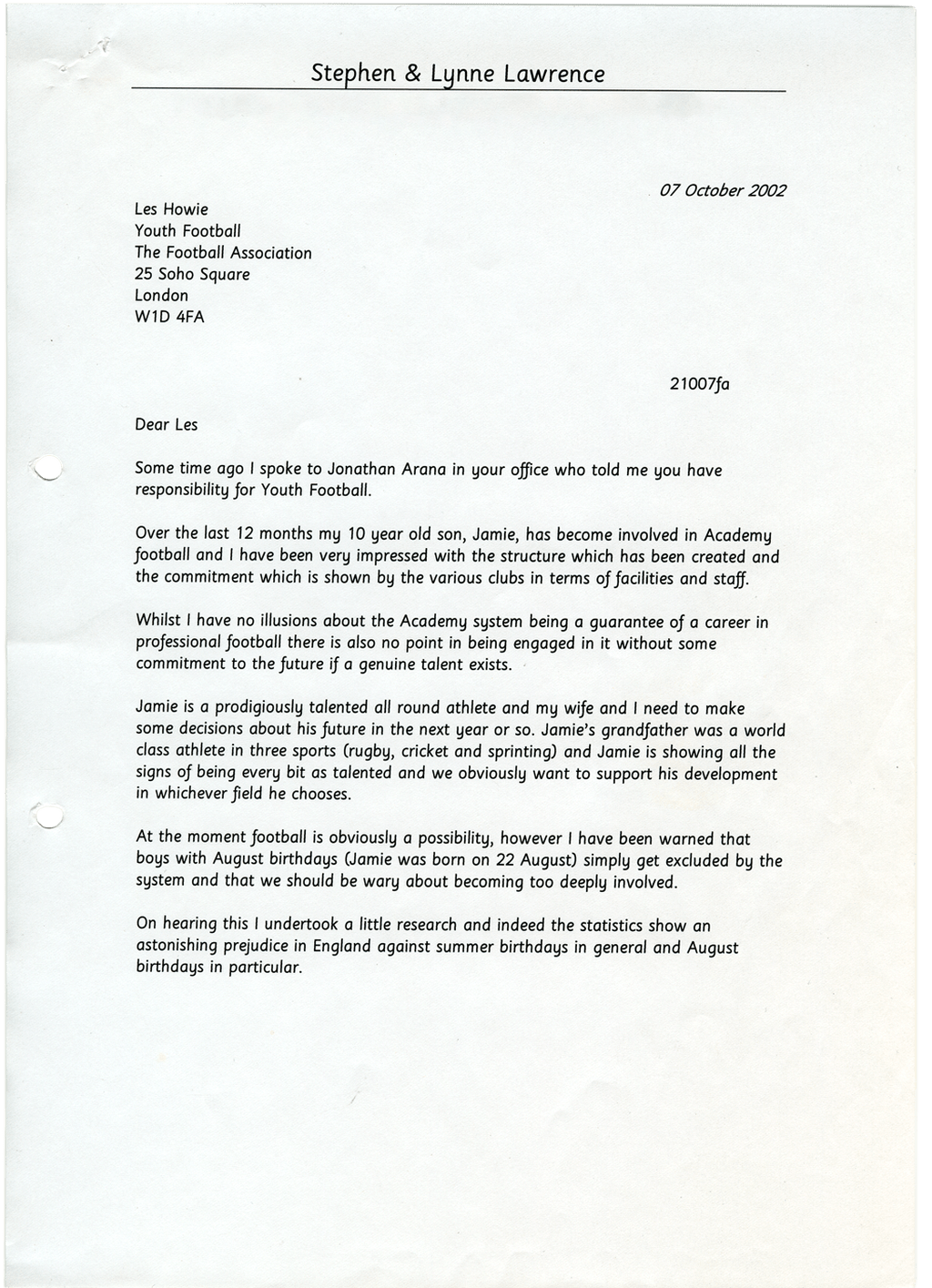

What to say to that? Nothing. The conversation stopped. The man left, and Steve never saw him again. But his words echoed in his head. In the evening he searched Altavista, Yahoo!, and a new search engine called Google, until he stumbled upon a scientific paper: Hockey success and birthdate: The relative age effect.

The article described a curious fact: in Canada, a disproportionately large number of the best ice hockey players were born at the beginning of the year, in January, February and March. The authors suspected this was a direct consequence of grouping young players – like schoolchildren – into year groups.

Put more simply: both a child born on 1 January 1980 and another born on 31 December 1980 would be eligible for the same team. But the older child (born on 1 January) is usually taller and stronger – and so more likely to be selected for better teams.

The finding made sense to Steve, but this was ice hockey in Canada. What did that say about football? A couple of months later Steve found a paper about English football, Season of birth bias in association football. His gaze immediately stopped at a chart. The birth months of successful English players turned out to be just as skewed as Canadian hockey players’.

The difference was that the cut-off date in English football was September 1 (instead of January 1) – which meant that the September-born players were the oldest and August players – Jamie! – the youngest. The graph looked as if some talent-eating monster had bitten a large chunk out of these "vulnerable" months in the year – August, July, June, and May.

Two thoughts raced through Steve’s head. The first: clubs, coaches, scouts – they’re paid to find the best players but they overlook half the population? The second, more alarming: how would this affect August-born Jamie? Is this what that Unknown Man had meant?

We have to let Jamie go

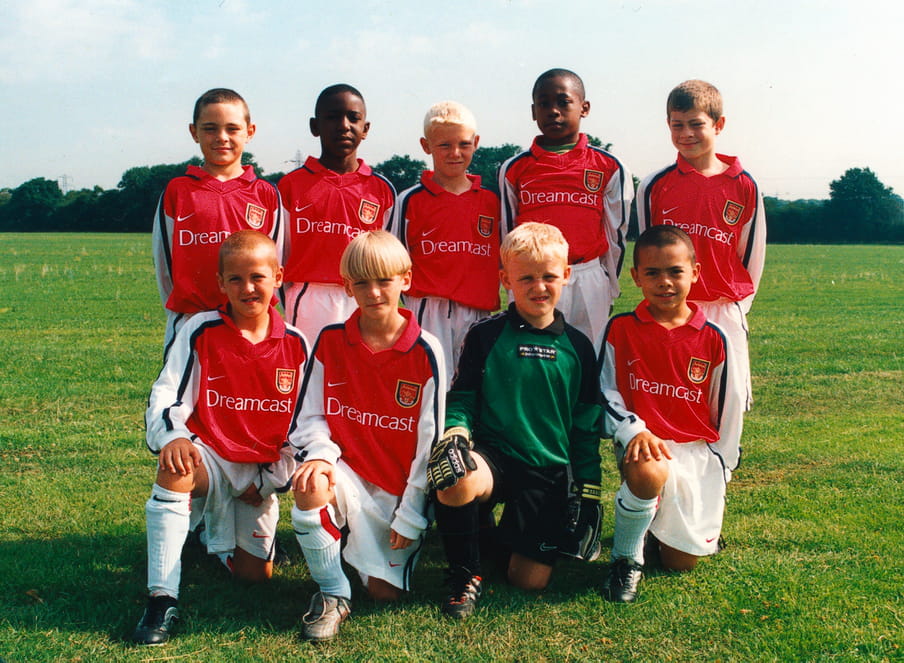

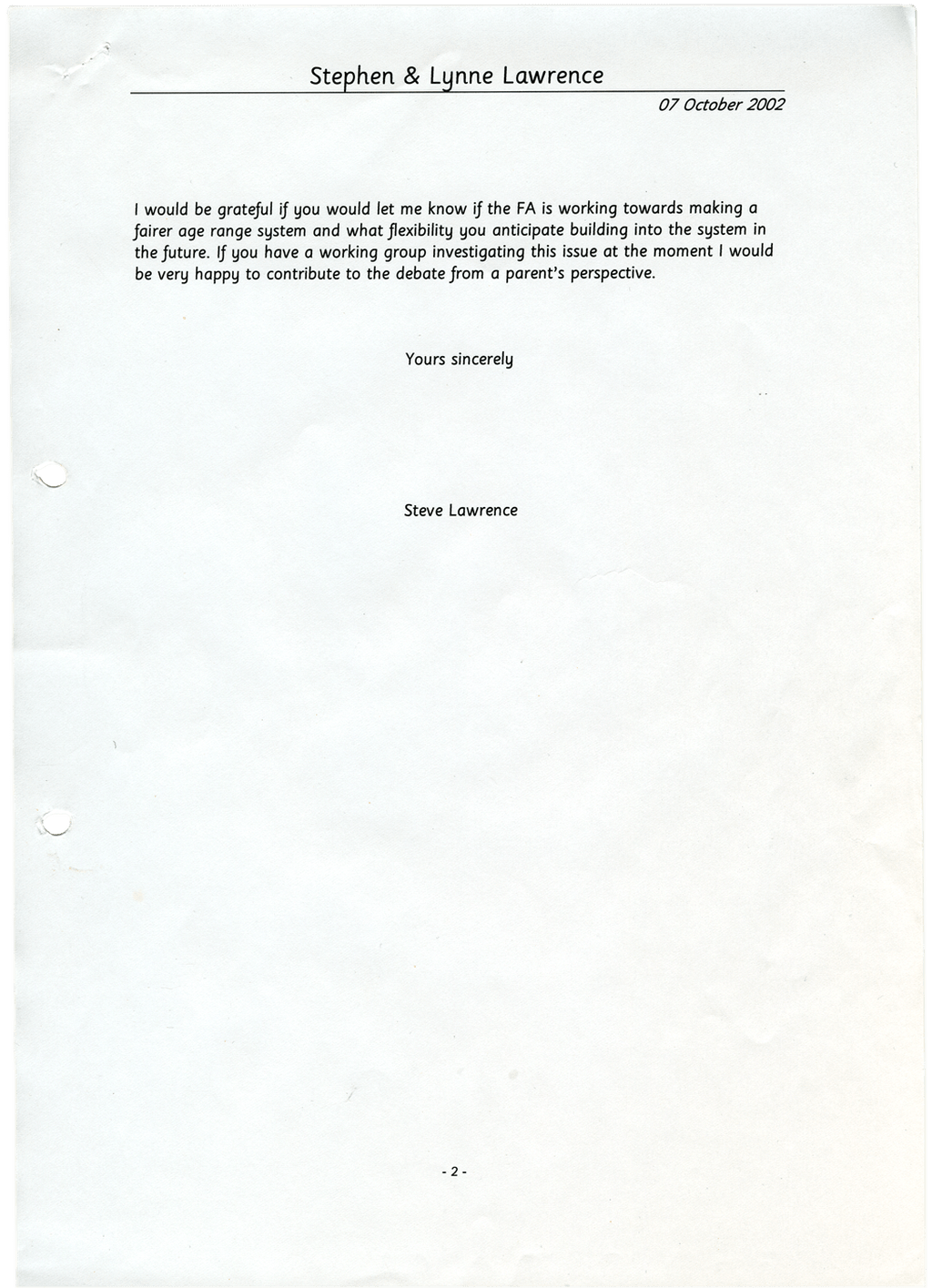

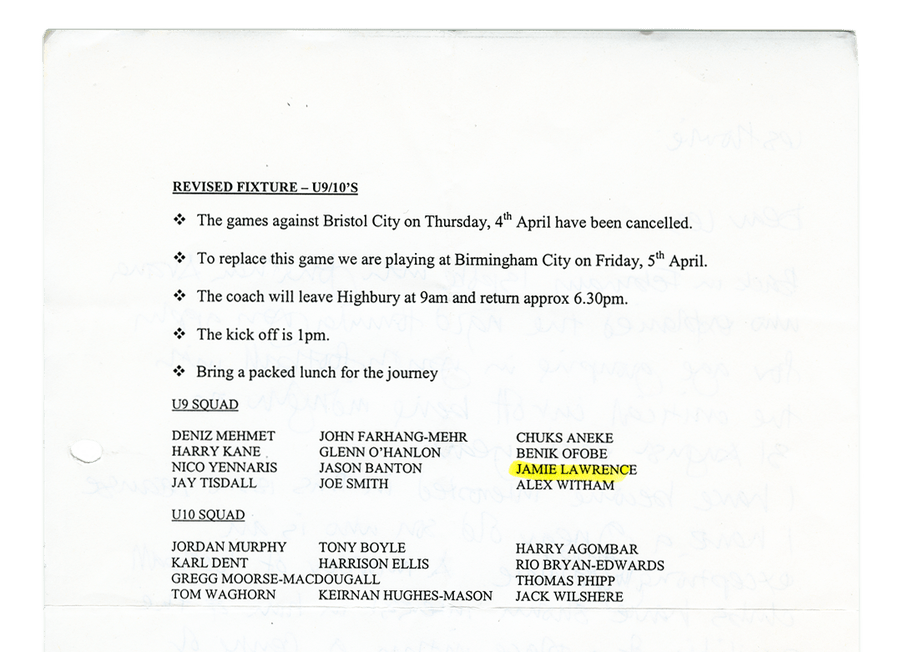

Steve didn’t have to wait long for an answer. Through the Arsenal Advanced academy Jamie was invited to participate in a tournament for Arsenal, in the summer of 2001. One of his team mates was a skinny, blond boy called Harry Kane, who would go on to be captain of England.

After the summer trial, Arsenal picked Jamie – and Harry – for their under-9s squad. The "cut off date" for inclusion was September 1, so Jamie – born August 22 – was nine days too old to be in the squad, but the FA gave him a special dispensation. In his first season, Jamie became one of the leading players of an all-conquering team of "wonderkids".

In the second year, in the under-10s, Steve noticed a change in Arsenal’s attitude towards Jamie. Other players received contracts, their own take-home kit and boots; Jamie didn’t. Other players’ families received regular feedback from the Arsenal coaches; Jamie and Steve didn’t. "I was always at Arsenal, but never really a part of Arsenal," Jamie recalls.

In spring of 2003, the club invited Steve and Jamie to a meeting. A man called Roy Massey came straight to the point. There wouldn’t be a place for Jamie at the academy next season. Steve had expected this. This is the paper, he thought. This is the relative age effect in practice.

In the under-9s and under-10s, while being one of the oldest players, Jamie had been a leader. In his "official" age group – where he would eventually have to move to and where he would be the youngest – they apparently expected less of him. Clearly, this was not about talent; it was just the bad luck of being born on the wrong day.

To Steve, the science predicted what would happen next. It is relatively younger players, theorised the ice hockey researchers, who "much more often experience frustration and failure”. Consequently, coaches had lower expectations for them, which rubbed off on the players’ expectations for themselves. "Frustrated by his or her limitations in matches, the [late-born child] may quit competitive sports”, another paper theorised.

As the train wreck loomed, Steve had a front row seat, just behind Jamie. “I remember thinking: I’m going to do everything I can to make sure that doesn’t happen,” Steve recalls.

The question was: how?

Knowing the problem didn’t solve it

Steve started reading everything he could find about the relative age effect. Almost every sport suffered from it. From football to baseball, volleyball to tennis: everywhere you looked, early-born, early maturing and early performing players were over-represented.

There was a common thread in the research: people, specifically coaches, could not discern between age and development, nor separate maturity from talent.

The principle also applied to the world beyond sports. Late-born children perform worse in education; late-born children were more often diagnosed with ADHD; late-born children were less often given high managerial and political positions.

The principle of dividing children by year-groups was devised with the intention of assessing children’s abilities appropriately and fairly; the actual effect was the opposite.

“The world is divided into two,” Steve explains. “Those who are born early, the lucky ones, and those who are born late, the unlucky ones.”

This insight powered Steve to plough on. Where research was lacking, he did it himself. He followed statistics courses, collected data, worked with leading sports scientists on papers, published in journals, and alerted the English FA to the issue. When no satisfying response came, he filed a complaint against the FA at the European Commission for "systemic discrimination" of late-born children.

When the Commission asked him for an alternative to the classical year system, Steve proposed to set a mandatory average team age. That way a coach couldn’t only pick early-born players. The European Commission wanted a formula that was "proportionate" and feasible. So Steve designed an app (after he had learned to code) which calculated the average team age (ATA).

The Commission is yet to rule, but Steve moved on, taking his proposal directly to clubs and national football associations and persuading them to run experiments. Further down the road, their experiments with an ATA may yet provide more evidence in support of his cause.

There’s delusional Steve again

All of that, he did – and more. The only thing he didn’t succeed in doing was the most important thing: helping Jamie win selection, by helping Jamie’s coaches to understand the relative age effect.

In the eyes of many a coach, Steve was just another delusional parent with exaggerated ambitions for his son; he just happened to be one with a fancier accent and a sheaf of complicated statistics in his back pocket. And Steve knew it: “A coach thinks you’re only saying that because your son stands to profit.”

From their point of view, what was a coach to do anyway? Select more late-borns? Lose more games? Lose his job?

Incentives for coaches worked against late-borns – against Jamie. After Arsenal, Jamie played for amateur clubs. Scouts from Queens Park Rangers, a professional side, spotted him. His sole year at QPR felt less like a season than a struggle – Jamie was either on the bench or played left-back, not his favourite position.

“Late-born footballers rarely play in their favourite position,” he says. "Which means they play below their level, get less affirmation, less playing time, and so on."

Slowly but surely, Jamie disappeared from the radar of professional football.

Until April 2008, when an email landed in Steve’s inbox.

In the Netherlands, Jamie is four months older

In the summer of the year before that email came, in 2007, Steve’s wife Lynne had worked as interim director of the Association Montessori Internationale in Amsterdam. The family followed Lynne, and Steve had emailed several Dutch professional clubs to ask if Jamie could train with them during those weeks.

One club responded: HFC Haarlem.

That summer, Jamie made an impression. In fact, they liked him so much that in April of 2008 Haarlem asked him to join them for the coming summer. “We would like to test Jamie once more and see if he is a possible player for us starting in August,” Haarlem’s academy manager Rene Moonen wrote.

Steve saw an opportunity – a move to the Netherlands could see Jamie beat the relative age effect. In the UK, the cut-off date for each junior team age cohort is 1 September, while in the Netherlands it is 1 January. At Haarlem, Steve explains, “Jamie would no longer be the youngest. In one stroke, he’d gain four months.”

And so, when Lynne became the full-time director at the Montessori institute, Jamie’s brother Tom stayed behind in London to finish high school, while Steve and Jamie went with Lynne.

Amateur social scientist Steve Lawrence performed an n=1 experiment on his son – with an astonishingly significant result. In Haarlem’s "B1" side – the under-17s – Jamie excelled at left-back. So much so, that the top Dutch side, Ajax, scouted Jamie. The next year he joined Ajax’s under-18s, as one half of the central defensive duo with current international Joël Veltman.

It was slightly surreal: within the space of a year, Jamie went from being a junior write-off in England to part of Ajax – one of the most famous youth football academies in the world. It was fuel to the fire of Steve’s conviction that only Jamie’s birthdate kept him from glory. Jamie had never had the positive feedback that an early-born received and still gotten this far.

How far could Jamie reach with the proper support and attention Ajax would surely provide?

Even the best youth academy prefers January

Sensing an opportunity, Steve emailed both the English and Welsh football associations to remind them of Jamie’s eligibility for their national youth squads. Surely, Steve thought, an Ajax player would raise interest? The mails remained unanswered.

Other obstacles arose in Jamie’s path. First, Jamie’s Dutch was mediocre – a disadvantage for a player whose strengths are good communication and intelligence. Then he was stalled – for months – by a groin operation, following a heart surgery (to correct an abnormally fast heart rhythm – according to Jamie, not that big a deal).

On top of all that, Steve discovered a whopping relative age effect at Ajax. Of 37 players in the under-18s and under-19s, only five were born in the second half of the year. Once again, Jamie was compared to older players, players who – unlike Jamie – had benefited from years of positive reinforcement.

Once again, Steve started an awareness campaign. But it wasn’t enough to secure Jamie’s prospects. When another Dutch team, AZ, showed an interest in Jamie in the spring of 2010, they considered a switch. Jamie had reached a critical point in a footballer’s development, and needed to catch up on missed playing time at a high level. He wrote to the head of youth training at Ajax, Jan Olde Riekerink, pointing him to argue his case on the relative age effect:

"Late-born footballers are very rare and I think deserve special guidance. I would like [Jamie] to receive some psychological training in ‘assertiveness’. He needs to become more assertive. We he was younger he would always be the captain ( ... ) and took significant control of each game. I would like to see that part of his character re-emerge."

Olde Riekerink reassured him – according to Steve – that Ajax “would take care of Jamie”. And so Jamie stayed with the club.

No 22-year-old soccer player is a ‘late bloomer’

But merely four months later everything changed. Head coach Martin Jol left Ajax for Fulham, and was replaced by youth coach Frank de Boer. In turn, Jamie got a new coach – Dick de Groot – who didn’t think highly of him. By the summer of 2011, Jamie was told that there was no more room for him at Ajax anymore.

Steve had always told Jamie that he was a late bloomer; that his chances would come; that he had to be patient. He didn’t tell Jamie what he actually thought: that the system discriminated against him. “I was afraid that if I told the truth, Jamie was going to see himself as a victim. And that this would affect his development like a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Of course, Jamie knew this age thing was affecting late-born players. What was harder to imagine was its impact on him. "He could be right, I thought. But I wasn’t convinced.”

That changed about two seconds after he switched on the television, on a summer day in 2011, to see an Arsenal player with a familiar name zip by: Emmanuel Frimpong.

Wait a minute, Jamie thought.

Years before, Jamie had played in the Middlesex cup final for a team called Enfield against Broadwater Farm FC, a club from the deprived London suburb of Broadwater Farm. Jamie marked Broadwater’s dominant striker, who was a at least a foot taller than him. Everybody at that game knew that this player wasn’t necessarily more talented – he was simply more mature. A temporary advantage, surely. But there he was, eight years later, on the television screen with the Arsenal stars: Emmanuel Frimpong.

For the first time, Jamie knew he was a victim. The train of thought which Jamie had, half-consciously, resisted over the years, now raced ahead at full speed. All the opportunities that players like Frimpong had received over the years had been denied to him.

His thoughts led to a pertinent question, which would haunt him in the years to come: "How could I ever catch up to this?”

After Ajax dropped Jamie, Steve – of course – got to work. He approached more Dutch clubs, securing new chances for Jamie at Sparta (one season) and RKC (two seasons). But at both clubs, Jamie remained stuck in the reserve sides. In summer 2014, he was almost 22 years old. He still had not played one minute in the first team of a professional football club. Time wasn’t starting to run out; time had run out. "I seemed unable to break through this ceiling," Jamie said.

No club had seriously considered the age effect. Nor was any club likely to take it seriously in the future. Nobody would look at a 22-year-old and see a late bloomer with potential. No club would think the way his father thought: that, given playing time and confidence, Jamie’s talents would blossom.

In youth football you could still find hope in patience: youth football is about development, about the future. Professional football is about performance. Right now.

The doubt crept into Jamie. Was he really a late bloomer? Or just not good enough?

To top up his salary from football, he took on data-entry tasks for his mother. In the evenings, he followed a course in sports management at the Johan Cruijff Academy. His talented feet straddled two worlds. One foot waited for a playing career at the top of his sport. The other anticipated a job off the pitch. But Jamie was competing with players who had both legs in football. This is how football careers end.

The club of recycled soccer players

But not Jamie’s. Not while Steve had anything to do with it. In June 2015 Steve called Jamie with good news: he had secured a trial at a Slovakian club called AS Trenčín.

At Steve’s request, Ruben Jongkind – the brains behind Cruijff’s ideas at Ajax – had recommended Jamie to Tscheu La Ling, an Ajax winger from the 1970s-turned-businessman, who had bought Trenčín. La Ling had set up Trenčín as a trading house: the club would buy players with a defect, whose careers hadn’t started for some bad reason, develop them and sell the players on at a profit.

Jamie fitted the bill. He had defects, but then so did Trenčín. No western European footballer dreams of a career in eastern Europe. The facilities were meagre, and his accommodation spartan. But Trenčín’s squad of third-hand players turned out to be surprisingly strong.

Jamie watched his soon-to-be teammates almost eliminate Premier League side Hull City from the Europa League. There were 20,000 spectators in the stadium; Jamie had never played for more than 500. In Slovakia, he says, "I went from absolutely nowhere to somewhere”. He signed a contract, played his way into the first eleven side, then won back-to-back Slovakian Doubles.

Suddenly, Jamie was on an upward curve. Suddenly, he recognised something he remembered having had a long time ago: confidence. La Ling’s club of recycled soccer players turned out first-rate material. His team-mates earned lucrative transfers to larger clubs in western Europe. Surely his time would come, too. He kept playing. His game improved.

But his transfer didn’t materialise.

"In the summer of 2017 it’s fair to say I panicked," says Jamie. "I was about to become a 26-year-old player who can’t get transferred from a club where getting transferred is the business plan."

But eventually, Jamie’s big break came in August 2018. Trenčín drew to play Dutch side Feyenoord in the final qualifier for the Europa League. For fans, matches like this represent a chance for glory. For the players, it’s advertising time. Scouts like to watch this type of game, for the opportunity to compare unknown players (Trenčín) with well-known players (Feyenoord).

Trenčín’s collection of misfit toys blew Feyenoord off the pitch: 4-0. For the first goal, Jamie had dribbled into midfield (remarkable), played a give-and-go with a team-mate (gutsy), and played a perfect pass across Feyenoord’s penalty area (rare, for a central defender). "Boom! Now I’m on the radar," I thought, "even while I was still on the pitch".

Suddenly, all sorts of agents wanted to help Jamie get a transfer to all kinds of clubs. Two weeks later, he signed for an elite side: Anderlecht, Belgium’s biggest club. It was a fairytale.

The please-go-away-letter

But Steve wasn’t done.

For years, Jamie’s father had heckled coaches and team directors, appealing for playing time and salary, his approach burnished by all kinds of statistics about Jamie. (At a certain point, Trenčín’s technical director refused to negotiate further with Steve about Jamie’s salary.) For years, he sent a stream of emails to remind the English and Welsh football associations of his son’s existence, excellence, and eligibility.

Jamie understood – yet also had become an expert in "vicarious embarrassment". Whenever Steve recommended him to a club, "I said: Dad, what do you think they’ll say? Of course you’re saying that, because you’re his father.”

Steve wasn’t bothered. He felt no embarrassment in respect of an industry that patently, stupidly, wasted so much talent. He wasn’t about to sit around waiting for an industry which didn’t take what it could have to give his son what he deserved. "What have you got to lose?” he asked Jamie.

The main reason Jamie wasn’t in the picture for the national football associations, Steve believed, was that he hadn’t been in the picture before. And the reason he wasn’t in the picture before, well, that was because he was born nine days too early. And so he plowed on.

By 2018, Steve could still see Jamie make the English national team, even when there were multimillionaires from Manchester City and Liverpool playing in Jamie’s position.

Jamie told him: "Dad, I’m not going to play for England." This time Jamie was right. In 2018, Steve got a rejection – "please-go-away-letter", as he puts it – from the English FA technical director, Dan Ashworth. "Being honest with you, I don’t see Jamie being ahead of the players we have in a similar position and similar age at this time."

When Jamie met Giggsy

What Ryan Giggs told the press conference on 5 November 2018 was true.

An employee of the Football Association of Wales had alerted his staff to Jamie’s existence. What the BBC journalist Rob Phillips had asked also pointed to the truth: "a member of the public" had alerted this employee to Jamie’s talent.

Steve.

Six days after Jamie’s transfer to Anderlecht – in late August – Steve called Mark Evans, international affairs officer at the FAW. Evans had known a digital version of Steve for years: Steve had sent Evans monthly email updates about Jamie’s performances at Trenčín. Evans had forwarded many of these messages to the coaching staff, who appeared to ignore them. “I suppose the Slovakian league isn’t as convincing,” Evans says.

Now that Jamie played at Anderlecht, the reaction was different. Albert Stuivenberg, Giggs’ assistant, went out to scout Jamie almost straight away. As it turned out, he fitted the profile Ryan Giggs wanted: a ball-playing centre-back. And so Jamie Lawrence became a Welsh international, his unlikely apparition inspiring the #jameslawrencefacts.

(Memo to all football fathers: Call the head of scouting at your national FA, all will be fine.)

A week after the press conference, on 6 November, Jamie met his new team-mates: Aaron Ramsey, from Juventus; Gareth Bale of Real Madrid. He practised singing the national anthem in his hotel shower: a language he didn’t speak. He learned the verses, phonetically, encouraged by Manchester United star Dan James.

And of course he met Ryan Giggs, the national coach and team-mate of Jamie’s childhood hero Eric Cantona, a living legend. Giggsy! Giggs invited his new recruit for a chat about his childhood, his interests, aspects of his passing game. "Thanks Jamie," Giggs said after half an hour, "go get some rest now, we’ll train later".

"All right, Giggsy,” Jamie replied, “See you later."

When he left the room, blood rushed to his head. Did I really just say Giggsy!? Jamie didn’t let the emotion show. He walked off as if nothing had happened.

As if he had always belonged here – in this hotel, this squad, this moment.

Jamie has so far played 6 caps for Wales and was expected to be in the Wales squad for EURO 2020. Anderlecht have loaned him out to German club St. Pauli after Vincent Kompany became player-manager at Anderlecht in the summer of 2019.

This article first appeared on De Correspondent.

Dig deeper

Why hard work and specialising early is not a recipe for success

Which is better: a generalist or a specialist? Conventional wisdom says the earlier you specialise, the greater your chances of success. But people who take their time and broaden their horizons make smarter career choices. In fact, they tend to be better at their work than specialists.

Why hard work and specialising early is not a recipe for success

Which is better: a generalist or a specialist? Conventional wisdom says the earlier you specialise, the greater your chances of success. But people who take their time and broaden their horizons make smarter career choices. In fact, they tend to be better at their work than specialists.