Maybe you’ve heard the story. How New York PR rep Justine Sacco lost her job last year after she tweeted the following text from the airport:

“Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!”

Sacco put her phone in airplane mode – and her tweet raced around the world, accompanied by enraged commentary on her appalling racism. Not long after she landed, she was axed, to the glee of Twitter users who had predicted it.

But Sacco, says The New York Times Magazine, is no racist. On the contrary.

“To put it simply, I wasn’t trying to raise awareness of AIDS or piss off the world or ruin my life. Living in America puts us in a bit of a bubble when it comes to what is going on in the third world. I was making fun of that bubble,” she later said.

Poor Justine. No one had gotten her irony. Even her South African relatives, supporters of Nelson Mandela’s ANC, were furious.

This kind of misunderstanding happens regularly on Facebook. The company’s Protect and Care team investigated status updates that had been reported as harmful (“this hurts my feelings”) and asked the presumed bullies about their motives.

Nine of the ten people questioned said they thought their Facebook friends would like the post or think it was funny, and that they hadn’t meant it to be hurtful.

Something is clearly getting lost in our written communication: context, subtext, humor, irony. Why is that?

A living corpse in the morgue

Written text seems unambiguous and factual. Often that’s an illusion. And not just online, as the following true story shows.

A woman is told that her brother has died. She goes to the hospital and asks to see the body. In the morgue, she touches her brother’s body. It’s warm. The woman thinks, that can’t be right! She also thinks she feels a pulse. She tells the nurse who’s standing by, “I think my brother is alive!”

To which the nurse replies, “Oh, no, don’t worry dear, it’s on this sheet of paper: he’s dead.”

The woman runs into the corridor and speaks to a passing doctor, who examines the body and says, “My God, this man is alive!” The doctor administers adrenaline straight into his heart. The man, no worse for his stay in the morgue, goes back to life as usual.

The story of the nurse was told to Scottish psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist by a reader of his book, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World.

In this thick tome, McGilchrist takes on the role of a philosopher, writing about the different ways in which the left and right hemispheres of the brain process external input, and how that has influenced the way we see and think over the past two and a half millennia.

According to him, the point isn’t so much what the two halves of the brain do, so much as how they do it. And the way the left brain interprets the world, says McGilchrist, explains the nurse’s behavior.

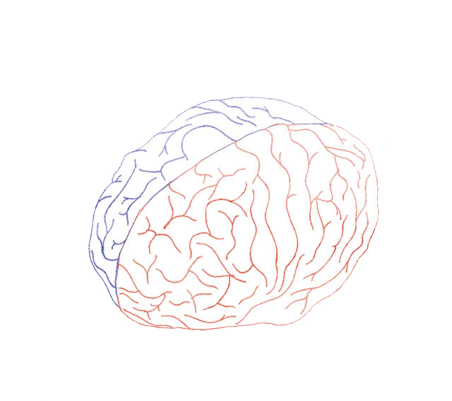

To understand that line of thought, we need a short introduction to lateralization: the specializations that each hemisphere of the brain has developed as it has evolved.

Illustration by Merel Corduwener for The Correspondent

The value of an asymmetrical brain

In humans and animals, both hemispheres of the brain are constantly active and in communication via the corpus callosum. For much of what we do, we need both halves, and of course there are many distinct regions of the brain, each with its own specialization.

But left and right also have their own special sets of tasks. For example, a baby chick prefers to use its right eye (left brain) to distinguish edible seeds from the pebbles among which they lie. Meanwhile, its left eye is scanning its surroundings. The right brain to which it is linked is in a state of vigilance.

This asymmetry has evolutionary value: it helps the chick keep from becoming someone else’s lunch.

The differences between left and right, which have little to do with left- or right-handedness, can be anatomically studied. It turns out that the arrangement of axons and cocktail of chemicals (such as hormones and neurotransmitters) differ significantly from one side of the brain to the other. The right hemisphere also contains relatively more white matter and the left hemisphere, more gray.

But the differences in the way the hemispheres work are even more pronounced. Hundreds of experiments in which one half of the brain had been damaged or was temporarily silenced through electroconvulsive therapy have shown that each hemisphere forms its own distinct picture of the outside world.

Someone else’s left arm in your bed

People whose right brains are damaged sometimes eat only the food on the right half of their plates, until someone turns the plate 180 degrees. Then they eat what’s on “the other right half.”

For these people, the left half of the world vanishes from their awareness. In his book, McGilchrist describes how these patients ask their caretakers to please remove that annoying arm on the left side of the bed – whether it’s paralyzed or functioning normally. Either way, it doesn’t belong to them.

When my grandmother was able to speak again after her stroke, she talked about “that red place on the map” when she meant Russia

These patients usually have no speech difficulties. But metaphors and other non-literal language escape them. They interpret the comment “it’s a little chilly in here” as factual information about the weather, rather than a polite request to close the window.

The situation is quite different in patients whose left brains have been damaged (we’ll look in detail at a concrete example later in this piece). They still experience the entire world as one intact unit, though some of its depth and detail are missing.

They often lose their vocabularies, but not their ability to form thoughts. Those thoughts are only expressed with difficulty even after they recover, however, and sometimes in metaphor.

When my grandmother was finally able to speak a little after her (left-hemisphere) stroke, she talked about “that red place on the map” when she wanted to ask how I’d enjoyed my time in Russia.

The global differences between the hemispheres

Iain McGilchrist is wary of reducing all the functionality of our brains to a rigorous division between left and right: of course it’s not that simple. But this animation from his TED talk does a beautiful job of summarizing the global differences.

Animation illustrating The Master and his Emissary

The essence of the divide:

The right hemisphere interprets reality as open, infinite, and ever changing. This is the alert, questioning, and empathic side of our brains. The right hemisphere presents reality.

To the left half of the brain, the world is closed, denotable, certain, and knowable, with a finite number of enumerable possibilities. Left represents reality.

Back to the nurse at the morgue. What went on in her head when she made the piece of paper the final authority?

Iain McGilchrist thinks she did what people constantly do: that is, test a thesis against known theories and assumptions. Against all those useful verbal information models, largely created by our left brains, that enable us to simplify an infinitely complex reality and which we can, as a rule, rely on.

But not blindly.

Nothing demonstrates that better than the following experiment, conducted in 1996.

The porcupine is a monkey

The subjects of the experiment had to solve the following syllogism:

- All monkeys climb trees.

- The porcupine is a monkey.

- Therefore porcupines climb trees.

Premise 2 (“the porcupine is a monkey”) is obviously nonsense. So while the syllogism may be valid, it isn’t true.

The experiment went as follows. The first time, the subjects were asked whether the syllogism was true in their normal state. They said things like, “A porcupine is not a monkey, so it isn’t true.”

The second time (a day or two later), they were asked the same question shortly after their left hemispheres had been suppressed by electroconvulsive therapy for 30 to 40 minutes. The subjects were even more adamant in their conviction that the syllogism was false, and they became emotional. They said things like, “Doctor, you’ve gone mad!”

But after temporary suppression of the right hemisphere, many subjects concluded that the syllogism was true. The conversations went like this:

- “Yes, it’s true.”

- “But you know the porcupine isn’t a monkey, don’t you?”

- “Yes, I know, but it’s still true.”

- “Why?”

- “Because it’s written here on this piece of paper.”

It happened time and time again, with different subjects and similar syllogisms. It’s true because it’s there on the paper: that’s how truth works, according to the left hemisphere of the brain.

If you turned the nurse’s train of thought into a syllogism, it would look like this:

- All people who have a death certificate are dead.

- The visitor’s brother has a death certificate.

- Therefore the visitor’s brother is dead.

But, you might say, the nurse’s right hemisphere hadn’t been suppressed, had it? Not by electroshock. But let’s assume that every death certificate she had seen up to that point had always corresponded to reality.

At some point, this verbal model replaced reality for her.

That is the message in Iain McGilchrist’s book. According to the psychiatrist, our right hemispheres are increasingly standing on the sidelines, as if we no longer need them.

Grasping objects, grasping language

The value of the simplified representation of the world that the left hemisphere provides us is undisputed, as Iain McGilchrist is quick to point out.

The left brain creates a world in which the left brain flourishes

Thanks to the left hemisphere’s ability to simplify the world and capture it in language, McGilchrist says, we have been able to create increasingly abstract and technological models of the world through the centuries – particularly since the Enlightenment.

During the Romantic era, we viewed the world a little more like our right hemisphere does: as something fundamentally unknowable and unnameable. But that’s clearly not how we view the world in 2015.

Aided by a steady stream of facts, bits, and bytes – the left brain’s modelmaking world – our instruments improve with every generation (and most people prefer to grasp them with their more fully developed right hands).

Since the industrial revolution, we have accomplished technological feats that enable us to dramatically alter the world to suit us.

The ability to grasp with one’s hand and the ability to grasp language, McGilchrist says, are naturally related.

But the consequences of the left brain’s manipulations are clearly not just positive. Kafkaesque bureaucracy would not exist if we were not equipped to reduce reality to a series of checkboxes. We violate the natural world with our digging and drilling and urban expansion.

And our once-simple barter system has morphed into a worldwide web of financial markets so complex that at present – and this has been said so often that it almost no longer surprises us – no one understands how it works anymore.

With the left hemisphere, McGilchrist says, we create a world in which the left hemisphere flourishes: technology, letters, and numbers triumph ever further over nature.

And in that world, it’s the abstract, verbal, numerical, technological models and theories that flourish.

It’s a self-reinforcing mechanism.

The confabulator

The left hemisphere generates not only simplified versions of reality, but also – and routinely – nonsensical explanations for what happens.

In the 1960s, psychologist Michael Gazzaniga began studying patients whose corpus callosum had been severed. (At the time that was a treatment for epilepsy.)

One of Gazzaniga’s most famous experiments went as follows. The subject’s right hemisphere was shown a picture of snow. The subject (known by his initials, P. S.) couldn’t say the word “snow” – vocabulary is the left brain’s domain, and in a patient with a severed corpus callosum, the two hemispheres no longer communicate. But he could point to a picture of a snow shovel with his left hand.

He couldn’t do that with his right hand, because his left hemisphere hadn’t seen the picture.

Then the researchers showed his right hemisphere the picture of snow again, and his left hemisphere a chicken claw.

Again, the subject’s left hand chose the snow shovel: his right hemisphere had seen snow. His right hand chose a picture of a chicken; that corresponded to the chicken claw.

Then the researchers asked him why his left hand had chosen a picture of a snow shovel. P. S., whose verbal left hemisphere had no idea that his right hemisphere had seen a picture of snow, promptly declared that he had seen a chicken, and that he needed the shovel to clean out the chicken shed.

Our left brains can apparently fabricate a story in seconds that molds reality to our own theories. Subject P. S. didn’t state his conclusion as a suggestion, but as an indisputable fact, as if he didn’t have to think about it.

It is the nature of the right hemisphere to question this kind of self-invented theory. But in our increasingly abstract reality, which our left hemisphere mistakes for all of reality, it’s astonishingly easy for that step to get skipped.

Not as smart as we think

A summary of our story up to this point:

- We view our linguistic and technological models of reality as actual reality with increasing ease, in a self-reinforcing mechanism.

- We are capable of creating nonsense explanations on the fly to make our theories of reality make sense.

And that’s what happened to Justine Sacco: tens of thousands of Twitter users took her tweet literally. They thought her tweet made up all of reality. They didn’t realize how much information they didn’t know about her, and concluded that she was a racist.

Her naked words were interpreted the way they would have been by patients who’ve had a stroke on the right side of the brain, who think that “it’s a little chilly in here” means only that it’s a little chilly in here. That if the paper says a porcupine is a monkey, it must be true.

Sacco’s irony, an aspect of communication that requires our right hemispheres, just as poetry and metaphors do, was lost in the dry linguistic format she chose. (A wink emoticon would probably have done wonders.)

What’s more, her tweet fit the image that people have of racists. Without a trace of self-doubt, Twitter users concocted a widely accepted conclusion: Justine Sacco is a racist. To devastating effect.

One would expect that Sacco’s boss knew what kind of person the company’s director of corporate communications was, and thus that Sacco’s tweet wasn’t meant to be taken literally. But in the world of corporate communications, the impact of Sacco’s statement was more important than Sacco’s intention. The fallout reflected badly on her employer. So the company chose to let the model of reality prevail over actual reality, and fired her.

The body temperature of a chicken

Our brains have a third problem: we are more likely to believe something we’ve heard before than something new, even if what we heard before is nonsense.

Psychologist, behavioral economist, and Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman described in Thinking, Fast and Slow how easily we accept assumptions if they seem familiar to us:

“People who were repeatedly exposed to the phrase ‘the body temperature of a chicken’ were more likely to accept as true the statement ‘the body temperature of a chicken is 144 degrees.’”

According to Kahneman, this is the reason why politicians can so easily make their constituents believe a completely irrational message.

“The free market regulates itself.” “The Nazis are running the show in Kiev.” These are simplifications of reality that we create with the verbal, declarative left half of our brains.

We don’t automatically question the truth behind those ideas. It’s hard to conduct a reality check on theories that are bigger than the scope of our own lives.

If you write your idea in a font that encourages trust, Kahneman says, it’s even easier for people to believe a nonsensical claim.

All this means that we’ll accept the craziest theories as true, if we’re just exposed to them often enough. After I had lived in Russia for a while, for example, it seemed completely normal to me that you’re not allowed to take photos at metro stations and airports – “high security objects.” That’s just how the Russians are. Obvious, right?

Perhaps not. As soon as I’ve got some free time to think and am able to make room for my deeper feelings, I realize I’d like for things to be different.And in the West (and many other parts of the world) we’ve grown completely used to the idea of an economic, technological, and bureaucratic machine that is increasingly living a life of its own. That’s how Westerners are. Obvious, right?

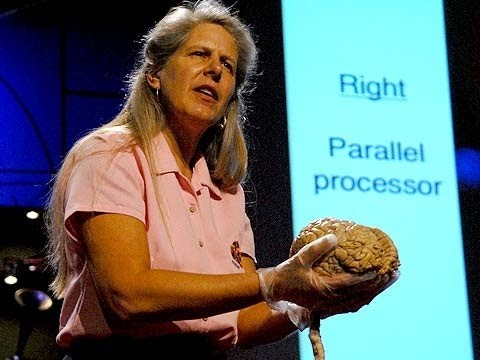

When the “brain chatter” stops

Is it a controversial idea that we can attribute the world’s major problems to our blind faith in a decisive but dogmatic and dominant left brain that’s good at making up stories? This, too, is just another model of reality. But perhaps it’s not such a crazy one.

On December 10, 1996, Jill Bolte Taylor (37 at the time) woke up with a pounding pain behind her left eye. She jumped on her exercise bike, waiting for the pain to ebb, but she couldn’t shake the feeling that she wasn’t in her own body.

In the shower, her regular train of thought – “brain chatter,” as she calls it – began to fragment and fall away. That was when she first thought she might be having a stroke.

Jill Bolte Taylor’s TED talk

Bolte Taylor is a neuroanatomist. In the four hours that followed, she experienced how her own left hemisphere, which she used so intensely every day in her research and whose workings she understood so well in theory, shut down.

The whole concept of 911 no longer existed for her

In her book My Stroke Of Insight, which she wrote after her recovery, she explains why she didn’t call 911. The part of her brain where the emergency number was stored was “swimming in a pool of blood.” The whole concept of 911 no longer existed for her.

At the same time, she was fully aware that she was experiencing an emergency and she needed to call someone. But who, and how?

The number of her work extension at the Brain Bank – oh, the irony – ran through her head. But her brain couldn’t find the numbers. While she remained perfectly alert and aware, more and more factual information was being lost in the flood. By the time she found the number of a close colleague, she could no longer read it.

Searching for the corresponding pictograms on the telephone, she typed his number in at the pace of a snail: her stroke was now 45 minutes underway.

It took her eight years to recover.

Liberated from the idea of self

Like McGilchrist’s The Master and His Emissary, My Stroke of Insight discusses the different roles each of the hemispheres play. In her book, Bolte Taylor draws much the same conclusions as McGilchrist. She also emphasizes that the left hemisphere is vital to the way we function:

“One of the jobs of our left hemisphere language centers is to define our self by saying ‘I am.’ Through the use of brain chatter, your brain repeats over and over again the details of your life so you can remember them. It is the home of your ego center, which provides you with an internal awareness of what your name is, what your credentials are, and where you live. Without those cells performing their job, you would forget who you are and lose track of your life and your identity.”

But this scientist also believes the left hemisphere is undesirably dominant and a source of discontent and dissatisfaction.

She discovered that when the stroke silenced the left half of her brain:

You can teach yourself to attach a little less importance to your “brain chatter” when it isn’t serving your needs

“Without a language center telling me: ‘I am Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor. I am a neuroanatomist. I live at this address and can be reached at this phone number,’ I felt no obligation to being [sic] her anymore.… I was no longer bound by her decisions or self-induced limitations.”

Bolte Taylor found herself in an egoless and euphoric, but also apathetic, state which she needed help to escape from. Her mother encouraged her to learn to speak again and to function in the world.

Once she did, she began traveling the world to tell people how wonderful it is to have a working left hemisphere again. But also how you can teach yourself to attach a little less importance to your “brain chatter” when it isn’t serving your needs.

Bolte Taylor also always asks audience members to consider donating their brains to a brain bank after death, so that more scientific research can be done to discover how they work. “You’ve always wanted to go to Harvard!” she sings in her self-composed “Brain Bank Jingle.”

Dumber than you think

So what can we do about the fact that we try to manipulate the world with the help of a brain that doesn’t interpret reality nearly as well as we thought it did?

Plenty is already being done. Jill Bolte Taylor is not the only one trying to make people aware of the suffering our blind faith in our own thoughts engenders, both in ourselves and in the world. We are gradually beginning to recognize that we’re not as smart as we think.

For example, each edition of the highly entertaining podcast series You Are Not So Smart by David McRaney covers a different type of self-delusion we engage in without even realizing it, including the many types of cognitive bias that exist. (The name cognitive bias was first used by Daniel Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky). The series is also available as a book, titled You Are Now Less Dumb.

The online community Less Wrong explores ways for people to uncover irrational cognitive biases, then use that knowledge to improve their own thinking.

And Iain McGilchrist? He’s also investigating how we can ensure that we once again prioritize what we know from experience, instead of prioritizing our theories. He believes that governments and educational institutions have a major role to play. In the project proposal for his next book, he zooms out to look at the world’s major issues:

“We take porcupines for monkeys because that is what our theory tells us they are. This leads us to a series of paradoxes, in which we believe we are setting out to achieve a certain aim – say, increasing global security by military intervention in the Gulf, or maximising market stability by employing ingenious programs that predict its movement – but end by achieving the precise opposite.”

Want to read more on this topic? I can heartily recommend the following: The Master and His Emissary by Iain McGilchrist, My Stroke of Insight by Jill Bolte Taylor, Who’s in Charge? Free Will and the Science of the Brain by Michael Gazzaniga, and Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman.

–Translated from Dutch by Grayson Morris and Erica Moore

More from De Correspondent:

Why talking is lying

Muslims, bankers, liberals – we use some terms so automatically, we don't realize they are actually little lies of language. And little lies have a way of turning into big lies.

Why talking is lying

Muslims, bankers, liberals – we use some terms so automatically, we don't realize they are actually little lies of language. And little lies have a way of turning into big lies.

Save the refugees, become a banker

What does it take to make the world a better place? An emerging philanthropic movement uses a radical new approach to allocating its resources. What can we learn from these uber-rational doers of good? And what should we be wary of?

Save the refugees, become a banker

What does it take to make the world a better place? An emerging philanthropic movement uses a radical new approach to allocating its resources. What can we learn from these uber-rational doers of good? And what should we be wary of?

A tree walks into a courtroom

Peter Wohlleben is convinced that the way we look at trees is about to change radically. His book The Hidden Life of Trees was a hit in his native Germany and is now being translated into 26 languages; the English version came out Tuesday. Does the book’s success indicate a sea change in our view of the world and ourselves?

A tree walks into a courtroom

Peter Wohlleben is convinced that the way we look at trees is about to change radically. His book The Hidden Life of Trees was a hit in his native Germany and is now being translated into 26 languages; the English version came out Tuesday. Does the book’s success indicate a sea change in our view of the world and ourselves?